The cultivation of the bureaucracy and the state machinery for concessions was matched by Dhirubhai’s uncanny appreciation of the stock market and his ability to use his trusted shareholders to play the market and augment the value of his company’s shares. This came to play in the Bombay Stock Exchange Crisis of 1982, referred to as a great ‘financial thriller’ whose protagonist, the audacious Dhirubhai, demonstrated his ability to ward off the powerful Marwari bear syndicate of Calcutta. It is instructive to read contemporary reportage on this to get a clear sense of how the businessman had consolidated his pre-eminence as a people’s person and a trader who could not be intimidated. Less than five years after the company went public with shares being offered, we find Dhirubhai battling the syndicate of Marwari brokers— ‘bear speculators’ who were bent on bringing down the value of the Reliance shares. They used the technique of short selling, to sell 11 lakh Reliance shares, valued at Rs 16 crore, hoping to bottom out the market but were pre-empted by Ambani’s brokers, who went about buying every share possible. The buying spree went on to create a huge and artificial spiral wherein the already overinflated Reliance stock rose to very steep heights from about Rs 125 in March to about Rs 202 in April. Amid this, Dhirubhai decided to deliver the sucker punch when, on the clearing day of 30 April, all transactions had to be squared and adjusted, Ambani’s brokers refused any postponement in delivery, knowing fully well that the bears had no shares to actually sell. As the India Today report of 31 May 1982 put it, ‘Knowing that the sellers would not have the shares to offer for delivery since they had indulged in massive short selling, Ambani’s brokers refused any postponements except at a staggering Rs 50 per share (involving the paying out of Rs 5.50 crore). This was obviously a penal rate meant to teach the bears a lesson, since badla charges rarely cross into double digits’. What followed thereafter was total bedlam at the Stock Exchange, which had to be closed for two days to salvage operations and a degree of respectability. As it became clear that Ambani and his brokers would not yield, the bears bought every conceivable share in the market. Reliance shares disappeared and prices skyrocketed; Ambani’s men bought up every share in the market, notwithstanding that this was not entirely legal. Detractors pointed this out repeatedly but admitted that the fiasco unmistakably demonstrated Ambani’s shrewdness and ruthlessness in defending his issues (debenture), which was the principal means to financing his ventures. Subsequent investigations by the government revealed that a non-resident Indian had invested nearly Rs 22 crore in Reliance in 1982–88; all of this had been channelled through companies registered in the tax haven of Isle of Man and under a single ownership that went by the name of Shah. The investigations could not prove any major rule violations. For the moment, Dhirubhai’s coup brought him an extraordinary aura of invincibility and built up his reputation as the ultimate stock messiah, the king of the share market, an image that appealed to thousands of Indians who were beginning to appreciate and participate in the culture of equity. The offers of Dhirubhai resonated with the desire of Indians to believe in what he said and to trust savings into his hands in the anticipation of handsome dividends. Just as his Vimal apparel resonated with the dreams of many Indian users, his shares became a valued asset to be invested in. It was a new class of Indians whom Dhirubhai appealed to—a new middle class who were not interested in small returns from unit trusts and post office savings but who were prepared to watch a new market in equity take shape and become willing participants in it. Dhirubhai was able to sense the growing aspiration of the middle class and make use of it, and in remaining committed to his shareholders, prepared to run the last mile. It was not as though he did not have to face his share of troubles, especially after the change of guard in the regime and when V.P. Singh became finance minister under Rajiv Gandhi and got a clean chit from him to launch a vigorous anti-corruption drive. This coincided with media interest in Dhirubhai’s dealings, which happened to engage the attention of the media industrialist R.P. Goenka, who went ahead with exposés to unravel the complex linkages between business and politics. More than anything, the media coverage initiated by journalists like S. Gurumurthy illustrated the conditions under which a very distinct, even distorted business milieu had emerged, one that Dhirubhai represented and was even partly responsible for.

Book Excerpt: India Before the Ambanis by Lakshmi Subramanian

India Before the Ambanis is a history of Indian business through the lens of individual enterprise. It focuses on western India, the country’s leading commercial, financial and industrial hub in the mid-19th century

Battling the State and the Fourth Pillar

The growth of Reliance from its first mill in Naroda to the Patalganga refinery, the creation of an equity market, a spate of successful debenture issues to help support worsted mills, modernization projects, and the financing of polyester filament yarn (PFY) manufacture were marks of extraordinary success and dynamism. This, however, did not happen in a vacuum. Without detracting the intrepid energy and ambition of Dhirubhai, it is nonetheless important to place his success in perspective and in relation to a political establishment that went far beyond its remit to favour him.

Bookmarked

Take a look at what’s new in the business section of Amazon’s bookshelf

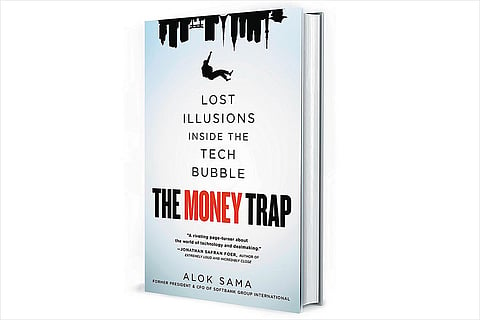

The Money Trap

Alok Sama

Published: September 2024

The book is about the author’s personal experience alongside SoftBank founder Masayoshi Son who wants to be remembered as ‘the crazy guy who bet on the future’ and whose mission is ‘happiness for everyone’. Written with self-deprecating wit and honesty, it provides an insider perspective on an industry that is disrupting our daily lives.

Gambling Man: The Wild Ride of Japan’s Masayoshi Son

Lionel Barber

Published: October 2024

The book reveals the man behind the money, what drives him, why he matters and what he plans for his next act.

The Nvidia Way: Jensen Huang and the Making of a Tech Giant

Tae Kim

Published: December 2024

The book describes how Nvidia saw the coming AI wave sooner than anyone else, and how it bet its future on a technology that had not yet arrived.

The Ambuja Story: How a Group of Ordinary Men Created an Extraordinary Company

Narotam Sekhsaria

Published: September 2024

The book is a case study of a company that broke stereotypes such as cement production cannot be an environment-friendly activity and good cement cannot be cheap.