In the summer of 2019, ahead of the 17th Lok Sabha elections, the Narendra Modi government made an audacious announcement: it said India would become a $5trn economy in the next five years if it returned to power. This was a staggering claim. Because for this to come to fruition, the Indian economy would have to consistently grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of at least 8.5%, a feat few economies of comparable scale have ever achieved.

The Wrath of the US Dollar and the Sisyphean Pursuit of Viksit Bharat

India's story of becoming a developed country resembles the life of Sisyphus, the character in Greek mythology who was condemned to roll a boulder up a hill only to see it roll back down

The path to this was laid bare in the Interim Budget. The Budget was seen as more of a manifesto of intent than a fiscal blueprint. The manifesto rested on the premise that the structural reforms brought in by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government during its first term (2014–19) had laid the groundwork for this economic leap. The government and the economy’s chief stakeholders felt confident.

And at that time there was no reason to think of that confidence as misplaced. Narendra Modi’s first term had seen sweeping economic reforms: fuel prices had been deregulated bringing in money that could be used to build infrastructure, the goods and services tax (GST) was introduced to unify the country’s fragmented marketplace, and a host of other changes were made to improve ease of doing business.

Such was the mood within the government that every minister came up with their own optimistic projections about the Indian economy. And soon, what started as a target to achieve a $5trn economy by 2024 snowballed into a target of turning a $30trn economy by 2047, a mark that would put India in the club of developed nations. This number though, even at the time, felt more aspirational than empirical and shaped as much by political rhetoric as by financial forecasting.

Yet, never before had the world’s most populous nation exuded such confidence in its ability to scale. One of the reasons for this optimism was that over the past three decades, India’s resistance to capitalism had waned. And with Narendra Modi at the helm, policymakers believed India could match the speed of growth of its neighbour China. For decades, a section of Indian policymakers had aspired for the China approach. At that point, it felt possible. And if this were to succeed, India would finally claim its rightful place at the global high table.

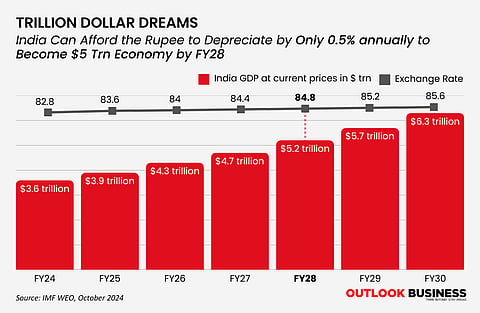

But 2024 has passed. And the $5trn economy dream is still just that—a dream. And the government is having to recalibrate its timelines. A recent finance ministry note says India is now expected to become a $5trn economy by 2028–29.

Assault of the Pandemic

The first hit to the ambitions was the pandemic. In 2020, when the covid-19 pandemic hit, India’s economy was showing promise despite a slowdown, having grown at a CAGR of around 7.5% during the Modi government's first term. But as the pandemic brought the global financial system to its knees, Indian economy’s journey stalled. The pandemic disrupted supply chains, shuttered businesses and wounded the very structure of the economy. The next year, the Indian economy contracted by 5.8%. And after growing at over 7% for three consecutive years, the economy is estimated to settle at 6.5% in fiscal 2025.

The pandemic hit consumption the hardest. And that has struggled to recover. Demand post pandemic has remained uneven. “The economy is still more than a year behind its pre-pandemic trajectory, implying a slack in the labour market. This weakens workers’ bargaining power, concentrating consumption growth at the upper end of the economic spectrum. This will take time to change,” says Neelkanth Mishra, chief economist, Axis Bank.

This concentration of consumption among higher income groups has happened because India’s recovery post-pandemic has been profit-led instead of being led by wage growth. The 2024 Economic Survey pointed out that more than 33,000 Indian companies had seen their pre-tax profits quadruple between financial years 2020 and 2023. On the other hand, private consumption, which makes up nearly 60% of India’s GDP, has struggled to regain momentum. An RBI report in 2022 said that it could take the Indian economy a decade to fully recover from the impact of the pandemic.

Ghost from the Past

This is not the first time the Indian economy has lost steam soon after gaining momentum because of a global event. In fact, India has gone through a similar experience this millennium itself. In the early 2000s, the Indian economy was just starting to gather power. The relatively new information technology (IT) sector was maturing, telecom was becoming exceedingly competitive and a new middle-class was taking shape that was more open and able to run a consumption-driven economy than those who came before them. India’s GDP was growing at around 9%.

And then came the 2008 financial crisis. What began as a subprime mortgage crisis quickly spiraled into a full-blown global meltdown, wiping out trillions from equity markets worldwide. The collapse of investment banking giants like Lehman Brothers exposed the fragility of the financial system, forcing governments across the world to intervene.

Yet, when it came to rescuing its own economy, the US opted for an aggressive monetary response—pumping billions of freshly printed dollars into its banking system through quantitative easing. Only the US could print dollars to the point of excess because the currency holds a unique status as the global reserve for international trade and finance. This privilege allowed America to absorb its financial shocks while shifting much of the burden onto other economies.

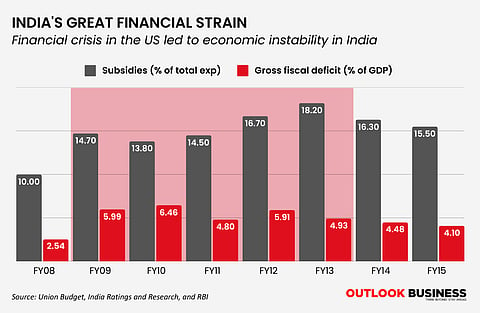

Fiscal and current account deficits widened sharply. In the next two years, the fiscal deficit would shoot up from 2.54% to 6.46%, burdened by the rising share of subsidies in expenditure. The Indian rupee fell from around 43 per dollar to over 55 per dollar in the next five years.

After the crisis came the taper tantrum. When the US Federal Reserve realised it could not expand its balance sheet indefinitely by printing dollars, it decided to taper its bond purchases, effectively reducing liquidity in the economy. As a result, investors who had poured capital into Indian markets in search of higher yields pulled out en masse. This sudden capital flight left the Indian economy, which was reliant on foreign investment, in a vulnerable position. The liquidity crunch led to financial strain for many Indian companies, contributing to poor business decisions. Around the same time, a series of corruption scandals also came to light.

From an economy showing signs of emergence, India found itself clubbed in a group unflatteringly labelled “Fragile Five”, along with Brazil, Turkey, Indonesia and South Africa. These nations shared a common vulnerability: large account deficits, high inflation and dependence on external funding. This was the time expressions such as “jobless growth” emerged.

And the Manmohan Singh government, until then comfortable because it had delivered solid growth and an optimistic view of the future, started losing support of the very middle class it had helped create. By the time India went to polls in 2014, the economic malaise had morphed into a political liability. The collapse of the rupee had become evidence of the government’s inability to manage external shocks.

The electoral outcome—that of the UPA losing power—was not a surprise. “People vote on the basis of their individual welfare and how it changes over the years. We are all economic animals, and we base all our decisions on individual economic experience,” Surjit Bhalla, an economist and former executive director at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), told Outlook Business in a recent interview.

Dominance of the Dollar

The American dollar's dominance and the ability of the American economy to change the growth path of nations far and wide has been a feature of the global economy since the Second World War. And India, like other emerging economies, has often had to feel the brunt of dollar swings and change in American economic policy.

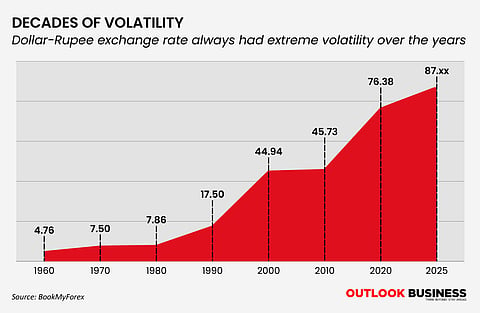

In 1947, when India threw off the yoke of British imperialism and emerged as a sovereign nation-state, the rupee held almost the same value as an American dollar. But two wars within two decades of independence—with China in 1962 and Pakistan in 1965—along with frequent droughts, bent the economy out of shape.

In dire need of foreign aid, India had to turn to the IMF and the World Bank for help. The global money agencies agreed to help, but in exchange demanded a devaluation of the rupee, boosting exports but at the same time making imports expensive for a country that was not producing enough to support its vast population.

Three decades later, during the balance of payments crisis of the 1990s, India had to devalue the rupee by 18% as part of a broader wave of reforms liberalising the economy.

Economists and policymakers are divided about whether devaluing the rupee has served India well. Arvind Pangariya, former chief economist of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the first vice-chairman of the Niti Aayog, writes in his book Trade Policy: 1990 and Beyond that the exchange rate management approach in the 1990s laid the foundation of India’s export competitiveness.

“The first step in building a trade-friendly ecosystem has to be a realistic exchange rate. We reaped the benefits of this approach in the 2000s. By letting the rupee depreciate from Rs 17.10 per dollar in 1990–91 to Rs 47.70 per dollar by 2001–02, we created a highly-competitive environment for producers of our exportable goods as well as those competing against imports, which were being liberalised alongside,” he writes.

On the other hand, successive RBI governors have on occasion intervened to maintain economic stability and have forced-stop a decline of the rupee. Former RBI governor Duvvuri Subbarao says, “Theory and practice tells us that exchange rate is not the sole determinant of export competitiveness. In fact, a weak rupee only gives us a temporary advantage. Sustainable competitive advantage comes from improved productivity, which in turn is a function of factors like the efficiency of our manufacturing processes, quality of infrastructure, cost-effectiveness and the skill endowment of the labour force.”

History is evidence that while a depreciating rupee offers a temporary boost to exports, its impacts extend much beyond trade. When the rupee declines, the size of the Indian economy in dollar terms shrinks, and thus its economic milestones seem farther off. To put things in perspective, in the three decades till financial year 2024, India’s nominal GDP grew at a CAGR of 12.4%. But in dollar terms, on account of the declining rupee, the economy has grown at a rate of only 8.9%.

In fact, if the rupee had maintained its exchange rate at the level it was in 2014, India would have already become a $5trn economy. But at the current exchange rate, the economy is expected to settle at around $4trn at the end of the current fiscal year. A weaker rupee leads to higher inflation and reduced purchasing power, further impacting consumption, which is already in poor shape.

If India really has to achieve its goal of becoming a developed nation by 2047, it needs to create economic systems that are able to remain stable in the face of global headwinds and unperturbed by the moodswings of the dollar. “We cannot afford huge swings in the exchange rate if we wish to preserve independence in monetary policy,” says TT Ram Mohan, a part-time member of the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council (PM-EAC).

A section of economists feels that an expensive dollar can severely strain the Indian economy, pushing it towards a crisis like the Sri Lankan bankruptcy crisis of 2022. India’s high import dependency, especially on crude oil, makes it vulnerable to the dollar, just like it happened during the 2008 financial crisis.

Dealing with Donald Trump

If the dollar’s outsized influence on the global economy was not a big enough problem already, the current uncertainty of the world economy caused by US President Donald Trump’s intent to close the trade gap with countries by imposing reciprocal tariffs threatens to upend prospects for the Indian economy just as its recovery from the pandemic has begun.

Experts say the uncertainty surrounding Trump’s policies may contribute to a further depreciation of the rupee—which already hit its lowest point in February at over 87 per dollar. Projections indicate that the rupee may fall to 90–92 per dollar over the next 6–10 months. “The dollar is likely to remain strong for an extended period due to Trump’s domestic and external policies. Additionally, the Federal Reserve is unlikely to cut interest rates which will reinforce the strength of the dollar,” says Subbarao.

If these projections prove true, India’s GDP may take a hit of around 0.1–0.6 percentage points, according to an analysis by investment bank Goldman Sachs. While the bank believes this drop will be manageable, a further rise in inflationary pressures and a decline in consumption threatens to seriously impact India’s growth rate in the longer run.

Billionaire social entrepreneur Sridhar Vembu, founder of Zoho Corporation, says Trump’s push for balanced bilateral trade between the US and India will drive up inflation in the country. “Now India will [have to] import more iPhones, GPUs [graphics processing units], fighter jets, whiskey and so on from America to balance the bilateral trade,” he recently said in a post on social media platform X. To not blow up its current account deficit, India will have to find ways to reduce consumer goods imports from China by increasing domestic production which cannot happen overnight, he said.

The Indian government, for now, has attempted to placate Trump by slashing tariffs on several items, including luxury cars and lithium-ion batteries, moves that are expected to help Elon Musk’s company Tesla. But helping Tesla could hurt India’s own plans of developing car manufacturing as consumers may find Tesla cars more attractive due to lower import duties.

“India has already reduced tariffs on some items of interest to US exporters and the Modi-Trump meeting has opened the possibility of more defence and energy imports to reduce the trade surplus. Higher imports of oil/gas and defence could close the trade deficit faster than tariff adjustments,” says Namrata Mittal, chief economist at SBI Mutual Fund.

Rising imports from the US on top of a weakening rupee could force India to cut imports from elsewhere, derailing its short-term economic goals, at least. Overall, this will inflate India’s import bills, raise energy and input prices, leading to an overheated economy, according to Ajay Srivastava, founder of Global Trade Research Initiative (GTRI). “Past 10-year export data says that the weak rupee does not help exports contrary to what economists say. In fact, it hits labour intensive exports the hardest while benefiting import-driven sectors with minimal value addition,” he says.

According to GTRI, for India to ensure long-term economic stability, it must carefully navigate the trade-off between growth and inflation while reassessing its currency management and trade strategies. “The reality, however, is sobering,” says Srivastava. He adds, “A significant portion of India’s $600bn foreign reserves consists of loans and investments that come with repayment obligations and interest, limiting their [the government and RBI’s] ability to effectively stabilise the rupee.”

What Happens Now?

India’s consumer price index (CPI) data reveals retail inflation, which averaged below 4% in the years preceding the pandemic, has been up at close to 6% over the past five years, primarily driven by a sharp rise in food and beverage prices—staples that constitute a substantial portion of the average India’s consumption basket. This surge in prices has in turn eroded the purchasing power of Indians.

The government, to its credit, is trying to absorb at least some of the impact of the economic whirlwind to come, as evidenced by its reduction in personal income tax in the 2025 Union Budget. The government is also planning to reduce GST rates on some items, according to the finance ministry, so that consumption does not fall to a point from which it will be difficult to recover.

Add to that, the Modi government, having learnt its lessons from the fall of UPA, has kept a tight grip on deficits. Before the BJP came to power, in the 2013–14 fiscal, India’s net fiscal deficit as share of GDP was 4.5%. In its first term, the Modi-led government brought it down to 4% by cutting subsidies on food and fertilisers. The pandemic drove up India’s fiscal deficit to 9.2% of GDP, but the Centre, through its razor-sharp focus on sustainable growth, brought it down once again. The fiscal deficit is estimated to come down to 4.8% at the end of the current fiscal.

But all these measures will only have limited impact. Because after all the Indian government can only cut its subsidy-spend (though even that might get difficult under sufficient inflationary pressures), and will have little to no control over the high import bill driven by the depreciation of the rupee.

The Modi government is already starting to feel some of the heat, as seen in the 2024 Lok Sabha election results. The $3trn increase in money supply by the Federal Reserve to the American economy in 2020 has contributed to the prolonged inflation that has burdened India for the past four years. A further increase in inflation will lead to economic distress, which may have political implications for the ruling party, and that in turn will affect its deadline to put India on a path to developed nation status in the next 22 years.

At the turn of the millennium, India’s foremost nuclear scientist-turned-President APJ Abdul Kalam, envisioned that India would become a developed nation by 2020. But 2020 has come and gone and India is still far from becoming a developed nation. Now, the target is 2047. But with the dollar’s outsized influence over the global economy and the swaying tides of American fiscal policy, there are chances that the Indian economy will face a series of economic challenges in the near future. If these projections come true, despite doing everything possible, efforts to make India a developed nation may resemble the life of Sisyphus, the character in Greek mythology who was condemned to roll a boulder up a hill only to see it roll back down.