I am going to live long to have more such celebrations,” an ecstatic Kushal Pal Singh told a gathering of A-listers at his birthday bash held at Udaipur’s Jag Mandir late last year. But then, who wouldn’t if they had the bootylicious Columbian pop star, Shakira, for company! In an adrenalin-charged evening, replete with aerial acrobats performing on heliospheric balloons and illuminated floating installations dotting the iconic Pichola Lake, it didn't really matter whether Singh was turning 18 or 80. The five-day bash that ended in Udaipur cost the family an estimated ₹100 crore.

But that’s loose change for someone with a networth of ₹24,934 crore—and that is after DLF has lost 84% of its market cap from the highs of 2008. Down south, it was the GVK family that stole the show in June when Mallika Reddy tied the nuptials with Indu Group scion Sidharth. The gala ceremony held in Hyderabad, too, cost an estimated ₹100 crore.

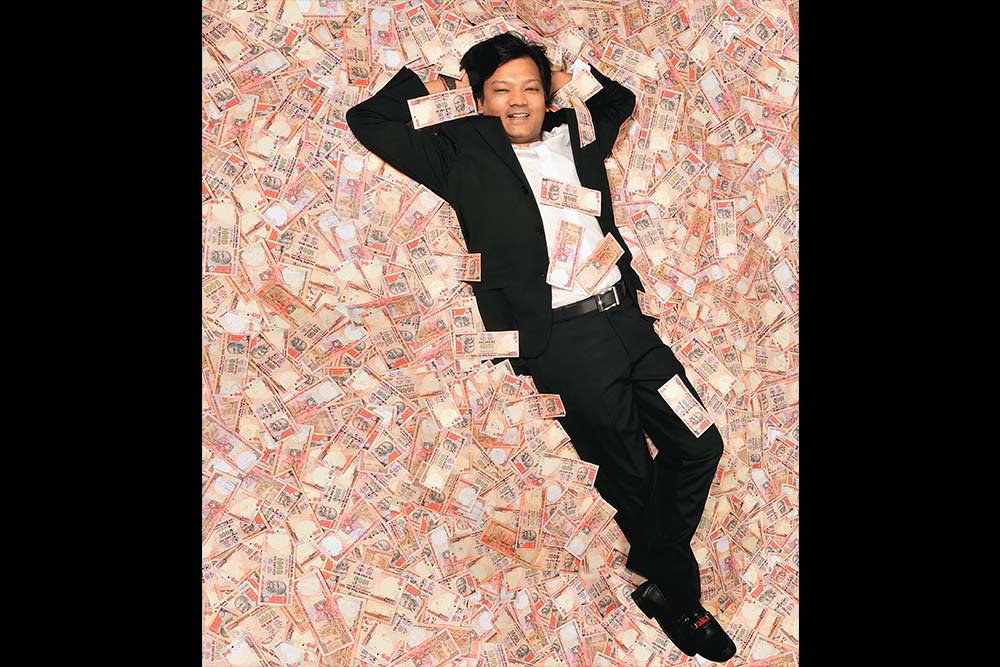

Welcome to the new face of live-it-up India that has no qualms about flaunting its wealth even at a time when the so-called macro is threatening to go from bad to worse. While two decades of reforms have worked wonders for India Inc, it’s the rip-roaring boom, which lasted till 2008, that lifted quite a few boats: giving birth to a new breed of entrepreneurs and bolstering fortunes of the ones already in business. So, it’s not surprising that the country’s wealth generation engine has been humming right through.

Underscoring this fact is Credit Suisse, which states that from January 2010 to June 2011, India’s total wealth increased by $1.3 trillion—the 6th-highest contributor of global wealth growth. In CY11, India’s total wealth reached $4.1 trillion and is projected to more than double to $8.9 trillion in the next five years. According to the Swiss financial services major, that is equivalent to the growth in wealth seen in the US over 30 years—between 1916 and 1946! Other reports only buttress the same point. Kotak Wealth pegs the number of high networth households, with a minimum networth of ₹25 crore, at 62,000 as of March 2011. And their total networth is expected to touch ₹235 trillion by FY16 from an estimated ₹45 trillion in FY11.

More importantly, the winds of change blowing across the economy are also visible in the attitudes of the wealthy. Our billionaires no longer squirm while flaunting their riches: be it jets, yachts or Maseratis. But when it comes to talking about their wealth and where they invest, the reactions range from a curt “Sorry, it’s too personal” to the likes of what the Adani group spokesperson had to say, “Do you ask Mukeshbhai what he does with his money, so why should Gautam Adani share this info?” Perhaps at a time when the income-tax sleuths are hot on the trail of 700 Swiss bank account holders, talking about money could almost certainly invite trouble. In fact, one South-based HNI (high networth individual) with whom we interacted, turned cold following an I-T 'survey'.

Luckily, we did manage to speak with some of India’s wealthy who were open about discussing their wealth allocation. Barring a few, the names mentioned might not sound familiar, but trust us, they’re loaded, with a cumulative networth upward of ₹18,000 crore. While in most cases, ploughing back money into their business remains a big priority, the HNIs are also following an asset allocation model that ensures wealth conservation. Unsurprisingly, among the various asset classes, equity is no longer in vogue.

The disillusionment with equities is also causing a lot of heartburn among wealth advisors, who are increasingly seeing clients make their own asset allocation calls. 40-year-old Priyadarshini Kanodia, the daughter-in-law of Datamatics founder Lalit Kanodia, who manages the company’s treasury investment and the family’s personal wealth, says, “The final call and asset allocation has remained my discretion. If one does not actively manage the portfolio and monitor it regularly, then no advisor can do any good for you.”

Whither equities?

Thanks to slowing economic growth and euro worries, the benchmark Sensex tanked 25% in CY11. The carnage was even worse in small and mid-cap stocks. The net outcome: equities turned out to be the worst-performing asset class of 2011. Pradeep Dokania, Head, Wealth Management, DSP Merrill Lynch, a veteran of many market cycles, says, “Equity has become a ‘humiliated’ asset class and the policy response within India is only compounding the misery of markets.” Concurs Jaideep Hansraj, Head, Kotak Wealth Management, “Today investors are questioning allocation to equities. They tell me—historically, equities have given a 15% compounded annual return; if you are getting

12% in government bonds, then why take the risk?”

Over the past one year several clients have moved out of equities completely or are in the process of doing so. Amit Jatia, scion of the BL Jatia family, whose businesses include the McDonald’s franchise in western and southern India, real estate and industrial lubricants, is already on the job. “Till around 2007, we used to have a high exposure in equities,” he says. “But, over the last four years, we have brought it down to 20% of our overall asset allocation.” And given that much of the client-advisor conflict has come about due to clients feeling the pain in equities, advisors are playing it safe for now. Abhay Aima, Head, Private Banking, HDFC Bank, says, “In 2008, clients refrained from selling. In 2011, they have refrained from buying. But advisors are not goading clients to take risk. Suppose the Eurozone blows up in your face three months down the line, you may have another down year. Then how do you face your client?”

While market volatility is a prime culprit, clients are also not shying away from blaming advisors for their woes. 67-year-old JP Thaparia, Owner,

Famy Care, has lost faith in the PMS (portfolio management services) platform. “In our seven-odd years of investing, we haven’t made any decent money,” says Thaparia, whose networth is close to ₹1,000 crore. “Despite all the talk, PMS has not delivered for us. So, over the past year, we have moved away from PMS and are more comfortable investing in mutual funds.” That said, Thaparia, whose investment kitty is around ₹300 crore, is scaling down his exposure from 25% to 20%. Sharing Thaparia’s disgruntlement is 43-year-old MN Kapasi of Excel Home Video Entertainment, home entertainment licensees for 20th Century Fox, MGM, and Aamir Khan Productions.

“At a 20,000 Sensex, all the PMS guys were pretty much saying the same thing—that the markets would hit 25,000,” says Kapasi, who has a networth of ₹100 crore. “I lost a substantial amount in the bargain.” And this loss of confidence is not helping the private wealth management business, which is already struggling with increasing competition. “With all the undercutting, it is becoming tougher to make money,” says Kotak’s Hansraj. “If allocation to equity reduces, then fee income reduces too. Equity assets give you yields of 100-125 basis points compared with 10-30 basis points for debt.”

Interestingly, while promoters of privately held companies are averse to investing in equities, it’s the opposite for those whose fortunes are largely linked to the stock market. Take the case of 60-year-old Venugopal Dhoot of the Videocon Group, whose networth Forbes estimates at ₹13,000 crore, or the 66-year-old Surinder Kapur of the Delhi-based Sona Group, whose flagship company is Sona Koyo Steering Systems. Dhoot has allocated 60% of his wealth towards equities—50% in the form of direct equities and mutual funds with a tilt towards infrastructure and 10% in multinationals, especially those engaged in pharmaceuticals and consumer goods. “I look for returns of around 15% per annum with a four-year holding period,” Dhoot says. “I will invest a lot more in equities in 2012 as there will be a lot of opportunities in an uncertain market.”

Kapur, too, is keeping his faith in equities. “It is a good time to be a contrarian,” he says. “A very important lesson is not to be overtly optimistic that the current problems will go away. But a couple of years from now, as the global economy recovers, Indian markets will give good returns.”

Growth in equities is driven by a cocktail of low interest rates and low inflation. While both the factors seem some distance away, Rajesh Saluja, CEO & Managing Director, ASK WealthAdvisors, says since we are entering 2012 on very low expectations; any slight improvement will lead to a surprise on the upside for equities. He adds, “Though the downside risk is a 13,000 Sensex, we believe the next three to six months will give a very good chance to build a portfolio.” However, Dokania of DSP Merrill Lynch prefers a more cautious stance, “Something appearing cheap does not mean it is cheap.

We are telling clients, ‘let the uncertainty become clearer, may be then we can take a bigger equity allocation call.’ The earlier consensus bottom was 15-16,000, but now we are hearing about a level of 11-12,000. Our worst-case scenario, however, is 14,500.” While for a 16,000 Sensex, a one-year forward multiple of 13 times appears attractive, given the long-term (16-year) average of 13.6 times, the swish set has already made its choice for 2012—debt, the same asset class that delivered for them in 2011.

Till debt do us apart

HDFC Bank’s Aima says, “Of every ₹100 that we got as inflows in CY11, ₹95 went into debt.” Saluja, too, has seen that play out in client meetings, he recalls. “If we were pitching equities—out of 10 clients only three gave money. If we were pitching real estate—seven out of 10 gave money. And if we were pitching bonds all 10 gave money.” That, in a way, sums up where investor bias was in 2011. High domestic interest rates have not only benefited local savers but overseas investors as well. The interest rate differential has been used by advisors like Alchemy to grow their offshore book by garnering debt assets in West Asia and the United States. Not only that, thanks to the Reserve Bank of India’s rate tightening spree—13 hikes since early 2010—investors are smacking their lips in anticipation of capital gains as interest rate head southwards.

“The trend across the board is to move from long-tenure securities to short tenure,” says Mohit Batra, Chief Executive Officer, Alchemy Private Wealth, adding, “Though government borrowing and fiscal deficit will pressure the 10-year bond, short yields will come down faster.” Saluja, too, is asking clients to focus on the shorter end of the yield curve. He explains, “There is not much difference in yield between the 1-year and 10-year bond. If interest rates come down, they will come down much more at the shorter end than the longer end. So, the impact of gains in the portfolio because of the compression will be seen in the shorter end.”

That’s precisely what has Datamatics’ Kanodia hooked. Of the 60% asset allocation in debt, 10% has gone to liquid instruments and the balance is in short maturity debt funds. “We are expecting significant appreciation from an MTM [mark-to-market] perspective,” says Kanodia. Another instrument that’s proving to be popular among HNIs is fixed maturity plans (FMPs), the biggest draw being their tax impact. If held for at least a year, the tax on FMPs works out to 10.3% (including surcharge), compared with 30.9% for a bank fixed deposit if an individual falls in the highest tax bracket. Says Thaparia of Famy Care, “FMPs, post tax, are fetching you 9.6%, which is not a bad deal at all.”

Tanya Goyal, the 48-year-old Executive Director, Mogaé Consultants, who takes care of her family’s finances, has also allocated 70% of the investment pool to FMPs. “These instruments give us steady returns of 8-9% per annum.” Mogaé Consultants, which is run by Goyal and her husband, adman Sandeep Goyal, had in 2011 sold its 26% stake in its JV back to Dentsu for a reported ₹240 crore. If Goyal is a fan of FMPs, Dhoot has a taste for infra bonds. Of his 40% investment in debt, 50% of it is tied up in infrastructure bonds and the balance in bank deposits. “The returns from bonds are steady and healthy enough,” says Dhoot. “More importantly, anything to do with infrastructure is what I look for. The reason comes from my own bullishness on the sector’s growth prospects.”

However, not all HNIs are looking at the relative security of FMPs and bonds. Take the case of Ajit Singh who, along with his brother Jasjit Singh, owns the ₹1,300 crore ACG WorldWide, the world’s second-largest hard capsules manufacturer. The Singh brothers, who have an investment kitty of around ₹700 crore (₹150-odd crore personal and the balance on the company’s books), have mastered the art of investing and making money in certificate of deposits (CDs). “We have invested around ₹500-odd crore in CDs at an average 16% across a portfolio of 100 companies,” says Ajit Singh, as he fishes out a document to show at what rate the company has lent ₹4 crore to the promoters of the Mumbai-based Aanjaneya Lifecare.

For listed companies, ACG takes shares as collateral with a market value of 200% of the loan amount. “We have around 60 brokers who bring to our table good investment propositions and, thankfully, we have never had to deal with rotten apples,” says the 70-year-old, whose grandfather was one of the contractors who built the Rashtrapati Bhavan in the 1930s.

Like Ajit Singh, 43-year-old Vinay Agarwal of the ₹500-crore Creative Plastic, a blow-mould recyclable plastics manufacturer, has also deployed 30% of his investment kitty in unsecured lending. “We get pre-tax returns of 15-20% per annum from such instruments,” says Agarwal, whose networth is over ₹1,000 crore.

Agarwal’s high risk appetite notwithstanding, Alchemy’s Batra is keeping clients away from debt instruments issued by NBFCs like Muthoot as the risk return vis-à-vis government paper is skewed. His justification, “In this environment I find it hard to explain to my clients why they have to park their money in a NBFC vis-à-vis the Government of India for a 150 basis point differential. If it was 300-400 basis point, perhaps it would be worth considering.”

The Realty Show

Apart from this rush into debt, investors have increasingly taken solace in real estate in all its forms, be it land, property or debentures issued by developers. HNIs have stepped in as white knights at a time when developers are hard-pressed for cash with both public markets and bank credit

drying up. “There is a lot of product innovation happening on the real estate side with many non-convertible debentures (NCDs) being floated by developers,” says ASK’s Saluja. “But the risk here is that some NCDs have originated from builders who don’t have the best reputation and clients are blindly buying them without proper homework because of the institution that is recommending it.”

Saluja does know a thing or two about real estate. While most advisory firms either direct their clients to third-party realty funds or their own realty private equity funds, ASK has raised two real estate funds raising ₹340 crore and ₹750 crore, respectively, entirely through HNIs. A third

offshore fund based out of Singapore open to both institutional and HNI money is in the pipeline. ASK’s first fund raised in 2009 has given a return of 30% year by focusing on residential mid-income housing within city limits of the top five cities. Saluja says, “We invest in a specific project rather than give loans to developers. An escrow account ensures that money goes only to the project unlike deals done at the developer level where you do not have control on the utilisation of funds.”

If project specific and developer loans are proving to be an attractive proposition, so is investment in land. Take the case of Aurangabad-based Suyog Machhar, the country’s second-largest thermocol manufacturer and a major supplier to Videocon Industries. Machhar is deploying 50% of his funds into real estate. Over the past five years, the 37-year-old chemical engineer has acquired land in and around Aurangabad at fairly low prices and is now developing a 300,000 sq ft residential project and a 350,000 sq ft commercial project in the city. “If the past five years were about buying land, today it’s all about developing it,” Machhar proclaims. "Of my 50% investment in realty, two-thirds will go towards property development.

The balance will be held in bank deposits since there could be interesting buying opportunities if property or land prices soften.” Land monetisation apart, some investors like Thaparia and Jatia are also scouting for land deals. “We are looking at opportunities in Maharashtra, Gujarat and Rajasthan since we have operations in these states and understand the markets better,” says Thaparia. “But we realise that the waiting period has to be upwards of five years.” Jatia, on the other hand, is looking at buying land in and around Mumbai with a view to monetising it within three years.

However, investors like Kapasi and Agarwal see better prospects in ready commercial and residential properties. “We started investing in office and residential space from 2007 till 2010 and stopped in 2011 as we felt that prices had to soften,” says Agarwal of Creative, who has deployed 50% of his family’s investment in real estate. “In 2012, we will relook at property investments, especially in the metros, where latent demand is clearly visible.” Kapasi, who has invested 70% of his personal wealth in real estate, sees better prospects in Mumbai. But not all seem to agree with this view. DSP ML’s Dokania says that since real estate has seen significant increase it may take a breather. He adds, “the attraction is there, return expectation is muted, and some HNIs are looking to monetise their holdings.”

Sum-of-the-parts

Every investor has a different approach and objective when it comes to asset allocation, which is why asset allocation in its truest sense can never follow a cookie-cutter approach. But the big challenge in advisory is that you want complete information from the client and at the start of the relationship that comfort may not be there. Hence, the advisory becomes myopic. Every HNI’s exposure to gold and real estate is not reflected in his financial portfolio. The appeal of real estate and gold lies in the fact that it is unorganised and provides leeway for a lot of unaccounted deals. Perhaps some gold exposure is now getting formalised through gold ETFs and that has added to the gold rush that has been underway for the past three years.

Going against the grain, Alchemy’s Batra has asked clients to reduce allocation to gold from an average 10% to 5-6% as the correction in the global gold price has been masked by rupee depreciation. His rationale for not completely exiting, “We expect currency instability to continue and are holding the reminder as a hedge against a falling rupee.” Kotak’s Hansraj continues to be a believer. He says, “We are asking clients to stick to their gold allocation; closer to $1,450-1,500 level is where we would want clients to buy more if they want to increase allocation.”

While some seek safety in gold others are seeking greener pastures. For example, Thaparia is pursuing opportunities in the education and healthcare with an objective to create a business big enough as Famy Care so that both his sons have the option of running independent businesses. Agarwal of Creative is setting up a ₹20 crore PE fund exclusively for SMEs to leverage on the company’s manufacturing expertise. Similarly, Jatia has allocated 15% of his investments toward picking up stakes in companies directly or investing via PE funds.

None of the diversifications are coming at the expense of the primary business, and they are ploughing back money in line with their companies’ growth plans. Goyal is looking at ramping up Mogaé’s presence in the digital business. “We are confident that the big story will be mobile commerce, which includes trading on the mobile.” Singh of ACG is looking at incurring capex of around ₹200-300 crore for the next couple of years, while Machhar has earmarked 20% of his investment kitty to fund his thermocol business.

As far as equities are concerned, clients seem wedded to the view that since equities have not delivered over the past five years, they will, for all you know, not deliver over the next three years. That, to HDFC Bank’s Aima, is a contrarian signal and a source of optimism. He says, “I think we should have a much clearer picture by March both domestically and whether the Eurozone crisis continues to loom or subsides. Allocation to equities could go up post Q1CY12 contrary to popular expectation of 2012 being worse or similar to 2011.”

But Kotak’s Hansraj is worried that the damage this time is deeper and apathy towards equities could last anywhere from six to nine months. He also expects the spate of government bond issues to further drain money away from equities. He elaborates, “There is ₹21,000 crore of bond issues hitting the markets in the next 30 to 60 days and it is going to be oversubscribed across the board. A significant portion of that money is coming from sale of equities. But for the bond issuances, fresh money would have perhaps found its way into equities.” For now investor action is echoing his thoughts. Clients are not seeing the India Shining effect—neither in government action or their portfolios.