On January 17, 2020, a defunct edible oil company emerging out of bankruptcy had a board meeting a week ahead of its re-listing, where it gave the go-ahead for a preferential issue of 18.67 million shares raising ₹130 million — the shares with ₹2 face value would be issued at ₹7 (premium of ₹5) –- to a management consultancy company incorporated only five months ago on August 9, 2019, with literally no business to show and two directors Ashish Jain and Tribeni Agarwal. While Jain is also on the board of Sunny Infraprojects, Agarwal is on the board of KR Handloom. In its communication to the stock exchange, the company said that this issue was done because it needed long-term “growth capital”.

After the preferential issue, ratified at an extraordinary general meeting (EGM) on February 20 at Noida, the consultancy will own 5.94% of the listed company. That investment of ₹130 million has shot up to ₹13.48 billion, as of June 5, at a price of ₹725 — that’s 100x in less than five months!

The bankrupt edible oil company we are talking about is Ruchi Soya, which was taken over in December 2019 by sole bidder Patanjali Ayurved, controlled by yoga practitioner-turned-businessman Baba Ramdev. The tiny, upstart management consultancy company that puts the best hedge fund in the world to shame is New Delhi-based Ashav Advisory LLP. Its investment in Ruchi Soya has done extraordinarily well, as on the back of very low trading volume the market cap has been pumped from ₹5 billion to ₹214 billion, post re-listing.

But then in India, having a baba on your side can surely be a competitive advantage.

Not so edible past

Ruchi Soya has a murky past. The company hails from Madhya Pradesh, the soyabean capital of India, where founder Dinesh Shahra began his entrepreneurial journey. He started with soyabean nuggets, under the Nutrela brand in the late 80s. Till date, it is the market leader in branded soyabean nuggets, with over 50% market share. Over the years, the company ventured into the edible oil business and even today owns some of the most popular cooking oil brands such as Ruchi Gold and Mahakosh.

While he spotted the right opportunity, Shahra was also said to be close to some of the public sector banks in Indore. “Those connections were instrumental in him getting large sums of loans swiftly,” says one banker who has known him. The joke in Indore was that Shahra would sit at the beginning of each financial year with some of the bankers to draw up the planned loan disbursements and how much would come to him. Typically, requirements related to collateral would be significantly relaxed for Ruchi Soya. It was a rapport that he cultivated diligently over time.

In 2010, his company was caught in an investigation by the Intelligence Bureau, which showed that a stock operator named Vimal Rathod had rigged prices of three stocks – KS Oils, Ruchi Soya and Karuturi Global – at the behest of C Sivasankaran. In May that year, Sivasankaran owned 13% in Ruchi Soya, when the stock was quoting at ₹100. Sivasankaran’s entry coincided with company’s expansion in refining capacity, purchase of agri land in India and overseas, and the buyout of Gemini edible oil brand. By the time Sivasankaran exited the stock in early 2013, it had halved to ₹53.

It was also the time debt had started to spiral. Later, in an interview with The Economic Times in 2017, Shahra had said, “The three years starting 2012 were terrible.” For the downturn, he blamed excess monsoon in one season, two consecutive droughts that impacted soya cultivation, and rising refined oil imports from Malaysia and Indonesia on the back of high export incentive to local players. It was also around this time that Shahra started punting in the commodities market, especially castor seeds, which was on the boil. However, an unprecedented crash in global prices of castor seed from a high of ₹5,100 in January 2015 to ₹3,051 per quintal in January 2016 dealt a crippling blow to Ruchi, which was already struggling in its core refining oil business.

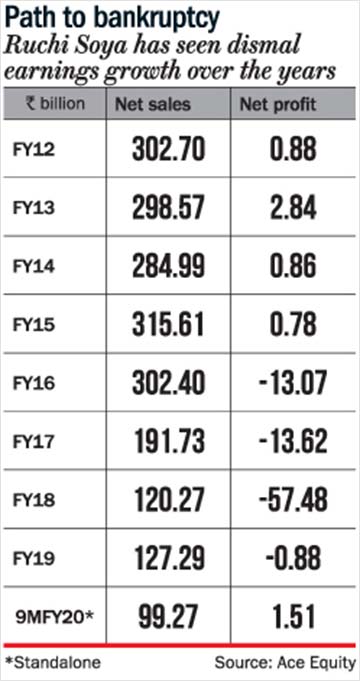

The castor price crash had prompted NCDEX to suspend futures trading, as a result of which Ruchi couldn’t liquidate its position and suffered estimated loss of around ₹4 billion. For the first time since its inception, Ruchi slipped into the red with a loss of ₹13.07 billion by March 2016 (See: Path to bankruptcy). Later that year, in May, Sebi barred the company from the securities market for manipulative trading in castor seeds. Deepak Shenoy, CEO at Capitalmind Wealth, an investment advisory, says, “Typically, in such cases it's a combination of bad bets and bad luck.”

By now bankers, especially private lender, IDFC Bank, had gotten jittery. Though IDFC’s exposure (₹2 billion) was only 2% of the total debt owed by Ruchi to the consortium of lenders; after several recovery reminders, it moved a winding up plea in the Mumbai HC. But since other creditors were working on a revival plan under RBI-framed guidelines for Joint Lender's Forum and Corrective Action Plan, the consortium’s lead banker IDBI filed a petition to oppose the winding up.

The HC turned down IDFC’s plea stating that it could sell its exposure to a new or existing lender, but it could not stay on and simultaneously oppose a restructuring. Incidentally, even as the company was struggling, in May 2016, Adani Wilmar and Ruchi Soya agreed to form a joint venture that would have the exclusive right to originate, market and distribute finished products from the manufacturing businesses of the two partners. In fact, Adani Group chairman, Gautam Adani, knew Shahra by virtue of being in the agricultural commodities business.

The relationship strengthened over time and a buyout was a natural progression. But since the lenders were in the process of creating a corporate debt restructuring plan, the Adani-Ruchi deal never fructified. Shahra’s financial position kept deteriorating as Ruchi Soya, by March 2017, piled up debt of over ₹120 billion. On whether the Adani deal could have rescued Ruchi, Shenoy seems unsure. “There was obviously some synergy that they had in mind. But exactly how that would have worked is only a matter of conjecture.”

By that time, the IBC had come into force and with no consensus emerging among the disparate set of lenders – PSBs, private and foreign lenders, in September 2017, two foreign lenders, DBS Bank and StanChart, moved the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) to initiate insolvency proceedings against Ruchi Soya. Against its $50 million exposure, DBS held fixed assets as collateral that included refineries in Kandla (Gujarat) and in Madhya Pradesh, while StanChart’s $52.5 million were secured by windmills in Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, besides refineries in Kakinada (Andhra Pradesh). DBS and StanChart declined to comment for the story.

But Shahra made a last-ditch effort to save his flagship. In November 2017, the company said it would sell 51% stake to Devonshire Capital, which focused on stressed assets, for ₹40 billion. Those who worked at Ruchi Soya were skeptical about the deal and maintained it was only a way to avoid being taken to NCLT. As expected, the tribunal termed the sale as null and void. In December 2017, IDBI Bank, declared Ruchi Soya, which was saddled with 26 financial creditors with an exposure of ₹93.85 billion and 1,304 operational creditors with an exposure of ₹27.62 billion, as a wilful defaulter.

Though the promoter refuted the charge of wilful defaulter, the company had already slipped out of his hands. With Shahra no longer in the picture, it was now left to the lenders and resolution professional, Shailendra Ajmera, partner - transaction advisory services at EY, to oversee the bidding process, which turned out to be a prolonged courtroom drama.

Highest bidder loses

While the initial race began with 28 bidders in the fray, by August 2018, Adani Wilmar was voted as the highest bidder with an offer of ₹54.74 billion – of which lenders were to get ₹43 billion. Adani’s bid was 24% higher than the second highest bidder, Patanjali's ₹41.60 billion. The other two bidders were Godrej Agrovet and Emami. But since only Adani and Patanjali’s bids were on a going-concern basis, the two were finally shortlisted. Going concern means bidding for the entire company and not just its assets.

Further, the bids were higher than the average liquidation value of ₹23.91 billion and closer to the fair value of ₹41.61 billion that the committee of creditors (CoC) had arrived at, based on registered valuers TR Chadha & Co and GAA Advisory’s report. The deal was in the bag for Adani as 96% of the creditors supported its bid. In fact, the top management at Ruchi Soya and Adani Wilmar had already begun a dialogue, since it was only a question of time before Adani would complete the buyout. An official, who was closely involved in the discussions, narrates how a list of names of those who would need to relocate to Ahmedabad (the buyer’s headquarters) was ready.

Adani Wilmar had already paid the earnest money of around ₹1 billion and all discussions centered only on employee and brand integration. By this time, Ruchi Soya COO Satendra Aggarwal was involved in closed-door meetings with his team to discuss a new advertising campaign for Nutrela, fully aware about the potential new owner.

It was decided to sign up Bollywood star, Madhuri Dixit, to endorse the brand and a formal announcement was made on August 14. Coincidentally, the approval from the Competition Commission of India came through on that very day for Adani Wilmar to acquire Ruchi Soya.

For all the mess that the edible oil company found itself in, it still had an impressive set of brands. The largest was Ruchi Gold with sales of ₹20 billion followed by Mahakosh with ₹10 billion and Nutrela’s ₹5 billion. These were mass brands and that interested Adani Wilmar, which already owned the Fortune brand. This was in addition to the commodity business, which was low on margin, but brought its own heft.

However, the story was far from over. Patanjali raised objections over Adani’s bid on the swadeshi vs MNC plank, and conflict of interest as the resolution professional’s legal advisor, Cyril Amarchand Mangaldas, was also advising Adani Wilmar. There was another peculiarity in this scuttling. In a letter to the lenders, Patanjali alleged that Adani Wilmar was ineligible to make the bid under Section 29A of the IBC. Usually, this is cited to keep bidders with past defaults out. But this time, the bidder was being challenged as director Pranav Adani was married to Namrata, daughter of Vikram Kothari, owner of Rotomac Group, who had defaulted on a loan. The charge was that Adani Wilmar was ineligible for being “connected” to another ineligible party. With the negotiation getting prolonged, in December 2018 Adani withdrew from the race citing the delay had resulted in deterioration of the asset.

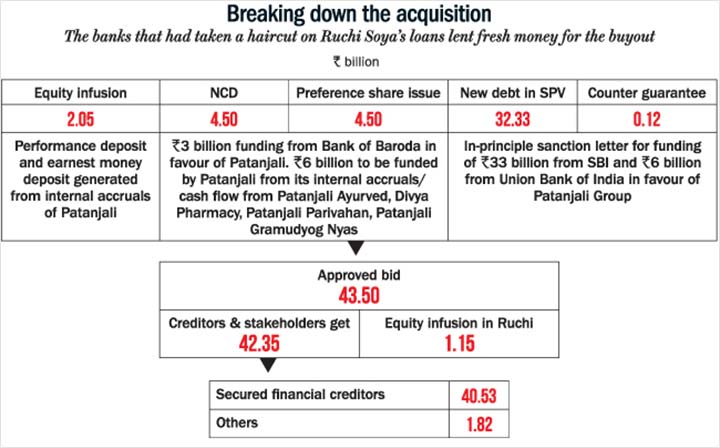

In April 2019, lenders voted on the Patanjali bid, which hiked its offer price to ₹43.50 billion, and in July, the bid also got NCLT approval. The bid meant that for the ₹93.84 billion due to financial creditors, Patanjali was to repay only ₹40.93 billion (43.61% of total dues). Operational creditors, against their claims of ₹27 billion, would get ₹900 million (33% of the total). The rest was ₹149 million towards workmen dues, ₹250 million for statutory dues and a counter guarantee of ₹118 million (See: Breaking down the acquisition). A SPV, Patanjali Consortium Adhigrahan, was created that was to be later amalgamated into Ruchi Soya.

DBS objected to the order stating that as a secured creditor it would have got 90% of the loan exposure in the event of liquidation and that the CoC should keep that in mind while distributing the proceeds. The CoC insisted that all financial creditors share the proceeds proportionately. DBS had to toe the CoC line after it lost its appeals, both at the tribunal and SC. What’s interesting is that, in the NCLT order of July 24, 2019, which cleared the bid for Patanjali, the break-up of the funding was given as follows: of the ₹42.35 billion agreed to be paid to financial creditors, Patanjali was to infuse ₹2.04 billion as equity into the SPV, ₹9 billion through a mix of NCDs and preference shares, ₹32.33 billion as fresh debt and a counter guarantee of ₹118.9 million. Of the ₹9 billion, Bank of Baroda was to fund ₹3 billion and ₹6 billion was to be invested by Patanjali through internal accruals. For the balance ₹32.45 billion (including the counter guarantee), Patanjali had managed to secure in-principle sanction letters from SBI for ₹33 billion and ₹6 billion from Union Bank of India.

Initially, according to sources in the banking industry, SBI was not keen on funding the buyout on its own. “The initial plan was for SBI to underwrite the loan and then downsell it to others. Once the proposal went through different stages of approval, across the credit committee and executive committee among others, the proposal was viewed as risky and the suggestion was to bring down SBI's exposure. That was when Union Bank of India was pulled in,” says the source.

While the court case by DBS and meetings of the CoC prolonged a closure of the deal, it emerged that SBI wasn’t exactly kicked about the prospect of funding Patanjali to the extent agreed earlier. The skepticism was justified – three rating agencies had downgraded Patanjali. In October 2019, ICRA and CARE downgraded the bank loan facilities of Patanjali Ayurved (PAL).

ICRA’s October 4 downgrade of PAL's fund-based cash credit limit instrument to BBB from A+ in April 2019 cited “lack of adequate information regarding Patanjali Ayurved Limited’s performance and hence the uncertainty around its credit risk”. The agency said that in accordance with its rating agreement with PAL, despite repeated requests, the entity’s management has remained non-cooperative. CARE was concerned that the sizable acquisition of Ruchi Soya, constituted 151% of PAL’s networth as on March 31, 2019. Media reports thereafter said CARE withdrew the downgraded rating at the request of Patanjali.

But the rating downgrades continued. On November 5, Brickwork Ratings downgraded the long-term rating for the bank loan facilities of Patanjali Food and Herbal Park Nagpur to BBB+. This was after the agency had already downgraded Patanjali’s ratings for loan facilities from Stable to Negative as it felt PAL’s debt-funded capex, including the Ruchi Soya takeover, could adversely impact its gearing and debt-coverage indicators. The other negatives according to Brickwork was the concentrated shareholding pattern, growing competition from larger FMCG players and the lack of a diversified board, which comprised the likes of Ram Bharat (brother of Ramdev) and his wife Sneh Bharat.

This turn of events clearly meant that lenders developed cold feet and dilly-dallied on any fresh commitment to Patanjali. In fact, in October, finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman commented at an event in Karnataka that banks need to stop being hesitant in giving loans to self-help groups and companies backed by spiritual leaders, which was construed as a remark aimed at the lenders of Patanjali. On November 29, 2019, a report in The Economic Times stated that SBI was reluctant to foot the entire bill and wanted other lenders who were to benefit from the transaction to chip in as well. “We have decided that all banks which will benefit from the write-back have to proportionately contribute to the loan as well. We alone will not take this full exposure. Patanjali is not a multinational company and there is little information about its financial position. We are not very comfortable with taking this risk on our own right now. Everyone has to pitch in,” a senior SBI executive told the business daily.

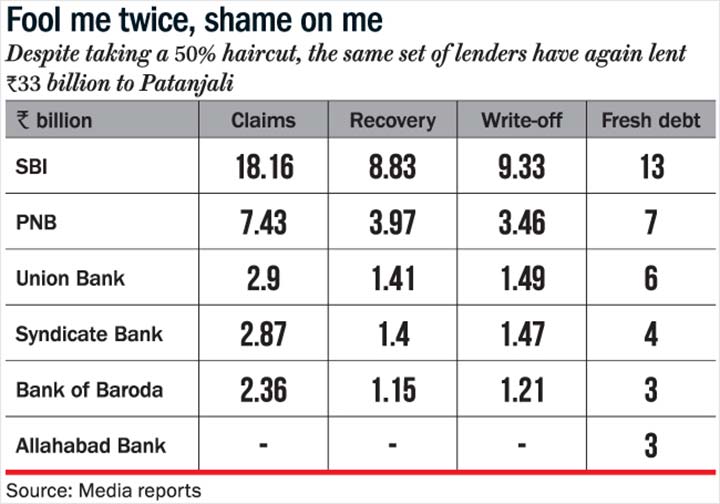

According to the previously quoted banking source, Patanjali was more than keen to complete the transaction. “Finally, Patanjali managed to get PNB and Allahabad Bank on board to part-fund the deal,” says the source. On November 29, Patanjali Ayurved in a statement from managing director Acharya Balkrishna communicated that it had got commitment of ₹12 billion with SBI, Rs 7 billion with PNB, ₹6 billion with Union Bank of India, ₹4 billion with Syndicate Bank and ₹3 billion from Allahabad Bank (See: Fool me twice, shame on me). When Outlook Business reached out to EY’s Ajmera, the resolution professional, to understand as to how a clutch of bankers ended up funding the buyout when only two banks were mentioned in the proposal cleared by the NCLT, he shot back, “The transaction has been reported 10 times in the newspaper, why are you taking me back to 2019? The transaction is done and money is paid… I don’t want to have the conversation any more...”

So ultimately, the ₹43.50 billion bid by Patanjali was funded predominantly through fresh debt from the very banks who took a 52% haircut on their earlier Ruchi Soya loans. In fact, as it appears, Patanjali hasn’t had to shell out a single penny from “internal accruals” as it claimed given that it had hardly any cash (₹370 million) on its books. Instead, the parent company at a board meeting on January 15th, cleared a proposal to avail ₹17 billion as working capital (WC) from a 11-bank consortium led by PNB. For availing the facility and also the ₹3 billion term loan from Bank of Baroda, Acharya Balkrishna pledged 50% of his shareholding in favour of PNB Investment Services. The company also hypothecated its entire stock of raw materials, finished and semi-finished goods across its factory premises, godown, transit stores, and book debts that included receivables. In addition to this, some banks took charge on Patanjali’s honey and chawanprash plants, besides fixed assets at Patanjali's units at Sonipat, Newasa and Tezpur. At the end of December 2019, following the amalgamation of the SPV, Ruchi Soya reported debt of ₹33 billion, on equity of ₹591.5 million.

It’s clear that PSU banks were once again nudged by vested interests into handing a highly favourable deal for Patanjali, despite concern on part of certain bankers. Outlook Business did not get any response to mails sent to SBI, PNB, BoB and Union Bank offices, despite repeated calls. Post the sanctioning, Syndicate Bank has merged into Canara Bank and Allahabad Bank into Indian Bank early this year.

Banking sources involved in the process concede the cloud around Patanjali was a huge cause of concern. “For all the hype, it was also a company with a presence in many product categories but had not delivered. Also, the management team was all about people close to Ramdev,” says a banker privy to the entire process.

It was against this backdrop that Ramdev came to Mumbai to meet the bankers last December, right after closing the deal, and then again a couple of weeks later. The banker quoted above recalls the Patanjali boss walking in with his Z-category security to take questions. SBI, as the lead banker, had already highlighted some of the concerns on behalf of the consortium. “The lenders wanted an assurance from Ramdev that the company would be professionally run unlike Patanjali, which remains a domain of his brother, Ram Bharat,” narrates the banker.

Ramdev was quick to give his assurance to the bankers on how the company would be run with a new management and it was on that basis that the transaction was funded. Right after these meetings, none of those concerns were addressed. Acharya Balkrishna, Ramdev’s confidante, was appointed Ruchi Soya’s CMD. And along with Ram Bharat, IndiaTV founder Rajat Gupta and Girish Kumar Ahuja of RJ Corp were inducted on the board in December 2019.

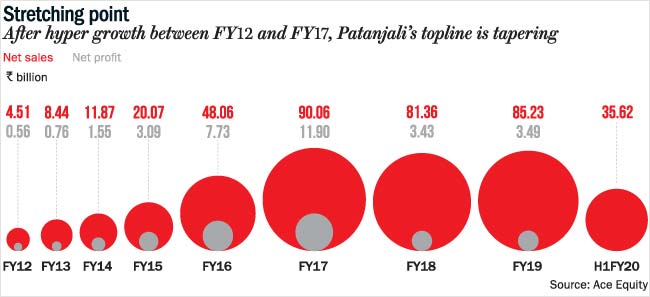

Patanjali’s acquisition of Ruchi Soya comes at a time when the former’s fundamentals have been rapidly deteriorating (See: Stretching point). Sales which galloped from ₹4.5 billion in FY12 to ₹90 billion in FY17 has been coming down steadily. Worse still, net profit which went up from ₹550 million in FY12 to ₹11 billion in FY17 was down to ₹3.5 billion in FY19. Net debt has gone up more than 10x from ₹2 billion in FY12 to ₹23 billion in FY19. The company’s receivables for FY19 stood at ₹26 billion, up from ₹21 billion in FY17, despite sales coming off from ₹91 billion to ₹85 billion during the same period.

That explains the eagerness on part of Patanjali to go after Ruchi Soya. “The objective of the buyout is to cover up the weaknesses in Patanjali. Ruchi Soya will give it the much needed revenue and cash flow,” says the unnamed banker. According to him, the edible oil brands with Ruchi Soya can grow and that is what Ramdev will focus on. “He is absolutely aware that Patanjali cannot fix its problems on its own. Ruchi Soya could save a troubled Patanjali.”

New avatar!

Effective December 17, the share capital of Ruchi Soya was reduced and consolidated to ₹591.5 million and, on December 18, Patanjali Ayurved took control of the management. The transition hasn’t been easy on the acquired company’s employees. One incident brings this out with striking clarity.

Early this year, Ruchi Soya’s 60-odd employees made their way to Haridwar. Generally, a visit to the holy city is considered a way to salvation. But the trip, for them, was a rude wake-up call. The venue for the official meeting, to present the plan for the company’s growth, was the lush green sprawling campus of Patanjali. Going by corporate tradition, the top team had worked for weeks to put together a presentation. On D-Day, COO Aggarwal, trooped into the meeting room where Ramdev was already present in his trademark saffron robe.

Just as the COO rose to make his presentation, Ramdev brusquely told the hefty Aggarwal, in chaste Hindi, “Yeh sab chhod do aur yoga keliye baithiye.” An executive, who was witness to what transpired, said even as the meeting abruptly ended, the next couple of days only made them uneasy about what lay ahead. “We were told it was a review meeting, but nothing was discussed by Ramdev or his team for the next two days,” says the executive, who has since left the company. The message was clear – the new owner would run the company the way Patanjali was run – ad hoc and obfuscated. “It became clear that many of us would not fit into the new organisation,” says the official. Five months since that episode in Haridwar, at least 600 employees, including the COO, at Ruchi Soya have moved on. That might create its own disruption, but it could well be what Patanjali wanted.

Ballooning value

Given that Patanjali’s own business is in a mess, whether the new owners will be able to unlock value in Ruchi Soya is anyone’s guess, but the bankers seem to have placed great faith in the shares of Ruchi Soya.

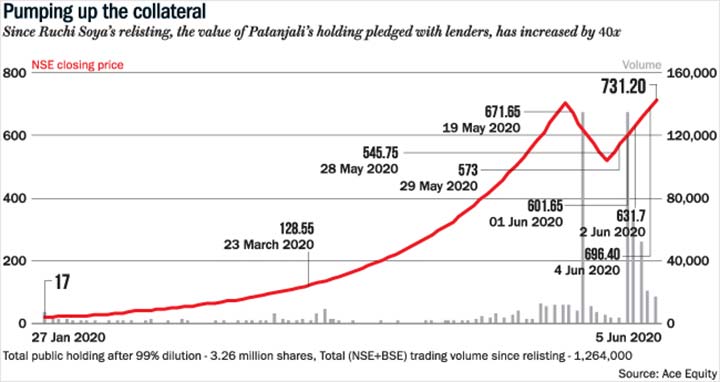

Ideally, the banks should have taken a charge on the assets of Ruchi Soya or the borrower Patanjali. Instead, the ₹32.95 billion loan, to be repaid by 2029, has been availed by pledging 99.97% (292.50 million shares) of the entire shareholding of 98.90% (292.58 million shares) of Patanjali Ayurved, with SBI Capital. It is not clear whether the bankers have also taken charge of the assets since Outlook Business could not get hold of relevant Ruchi Soya’s filings relating to charge on assets, except for SBICaps pledge creation, on the RoC website. The Form 8 filing provides clues regarding the solvency of a company, with details on its assets, liabilities, income and expenditure. Meanwhile, NSE and BSE permitted the company to trade as a new entity from January 27, 2020.

Since then the stock price, on the back of low public float of 1.10% (3.26 million shares held by 82,000 public shareholders), has touched a high of ₹736, inflating Ruchi Soya’s market cap to ₹217 billion (See: Pumping up the collateral). Magically, the collateral value of the pledged 99.97% holding has risen in tandem from ₹5 billion, at the time of re-listing. The stratospheric rise in valuation also helps in quelling unrest among retail shareholders who were diluted 99%.

While ‘watchdog’ Sebi certainly seems to be thinking this rise in stock price is natural and beneficial for all stakeholders; along with Patanjali, the prime beneficiary of this market cap created out of thin air is the non-descript consultancy company, Ashav Advisory, that provided timely “growth capital” to Ruchi Soya.

But, why is Ruchi Soya raising ₹130 million from a management consultancy to fund its need for long-term “growth capital,” as the company’s filing to Sebi states? It’s farfetched that a management consultant sets up shop to offer services and then becomes an investor.

Outlook Business did a check on Ashav’s antecedents. From the filings, it appears that Agarwal, who is also a director of KR Handloom, was given the go-ahead at a board meeting of KR Handloom on August 3, 2019 to invest ₹99,000 as capital and become a designated partner in Ashav. Interestingly, while the bank statement of Agarwal shows a balance of ₹440,000, that of Ashish Jain, also a designated partner and authorised representative of KR Handloom in Ashav, is a mere ₹219! The company has filed a document, dated February 10, 2020, that it has unsecured credit of ₹350 million from Yojana Management Tech Pvt Ltd, and on February 11, the registered office of Ashav was shifted from Delhi to Kolkata!

Presumably, it is this unsecured loan that was to be used to subscribe to the preferential allotment. The bigger discrepancy though is that Ruchi Soya’s filing to the stock exchange state that the ultimate beneficiaries of the preferential allotment are Mrs Tribeni Agarwal and Utkarsh Parasramka, another KR Handloom director. What then explains the negligible amount being raised from Ashav in exchange for a bumper payoff, with one of the beneficiaries not associated with Ashav to which the preferential allotment has been made?

“One can only hazard a guess that this company has been rewarded for a favour done. There is no bar on an entity that a company can issue preference shares to, you will never know the real face behind the company,” says Ambareesh Baliga, an independent market expert. “For all we know, as and when the shares get allotted and the one-year lock in period on those shares comes to a close, the share price will be quoting in four digits as the floating stock is low and some Institution(s) would be convinced to buy the ‘proxy to India’s consumption story.”

In response to Outlook Business’ query on the price appreciation on thin free float, the NSE spokesperson commented: “As per Rule 19A (5) of Securities Contracts (Regulations) Rules, 1957, wherein if the public shareholding in a listed company falls below 25% following the implementation of a resolution plan approved under Section 31 of the Code, 2016, such a company shall bring the public shareholding to 25% within a maximum three years from the date of such fall. Further, if the public holding falls below 10%, the same shall be increased to at least 10%, within a maximum 18 months from the date of such a fall.”

Given that after the allotment to Ashav LLP, public holding is 7%, Patanjali has the scope to place another 3% with an external investor, preferably a PSU bank or mutual fund. It also plays to the advantage of Agarwal and Parasramka! With the low float, they can dump the shares once the lock-in period ends and laugh all the way to the very same banks that helped create this tremendous “value”!

Questions sent by Outlook Business to Sebi went unanswered. The Patanjali spokesperson confirmed receipt of Outlook Business’s email questionnaire but said, “The company will not be in a position to respond on this.” At many points, we were faced with deafening silence. The reluctance is revealing and tells its own story.

Postscript

On May 15, 2018, Ruchi Soya had informed the exchanges that the Serious Fraud Investigation Office had initiated an investigation into the affairs of the company. According to media reports, the probe began on the basis of a whistleblower's letter to the Ministry of Corporate Affairs, tipping it off about a Singapore company’s relation with the promoter, the Shahra family, of Ruchi Soya. The report stated that the agency was looking into a ₹14.20 billion transaction carried out by Ruchi Soya with a Singapore-based company on the suspicion that the latter was a related-party and that the nature of the transaction was irregular. There has been no further development on that. But for now, Shahra, whose Twitter handle says he is a student of life, has turned over a ‘new leaf’ as a philanthropist with Dinesh Shahra Foundation. He is actively engaged in social causes, hobnobbing with spiritual gurus, espousing the cause of cow protection and has even authored a book 'Simplicity & Wisdom'. Well, he is also following the new CMD of Ruchi Soya, Acharya Balkrishna, on Twitter and retweeted his April 27 post on reading books for inspiration. It is a small world!