Manoj Aggarwal is trying to stay optimistic but it’s not easy. Newspaper reports have been saying that the price of Wave’s projects dropped 20% in the past two weeks. “I and many other brokers are concerned about the future of the Wave Infratech inventory we have already bought,” says Aggarwal, director of Pinnacle Properties, a Noida-based firm. “This should have never happened,” he says, shaking his head.

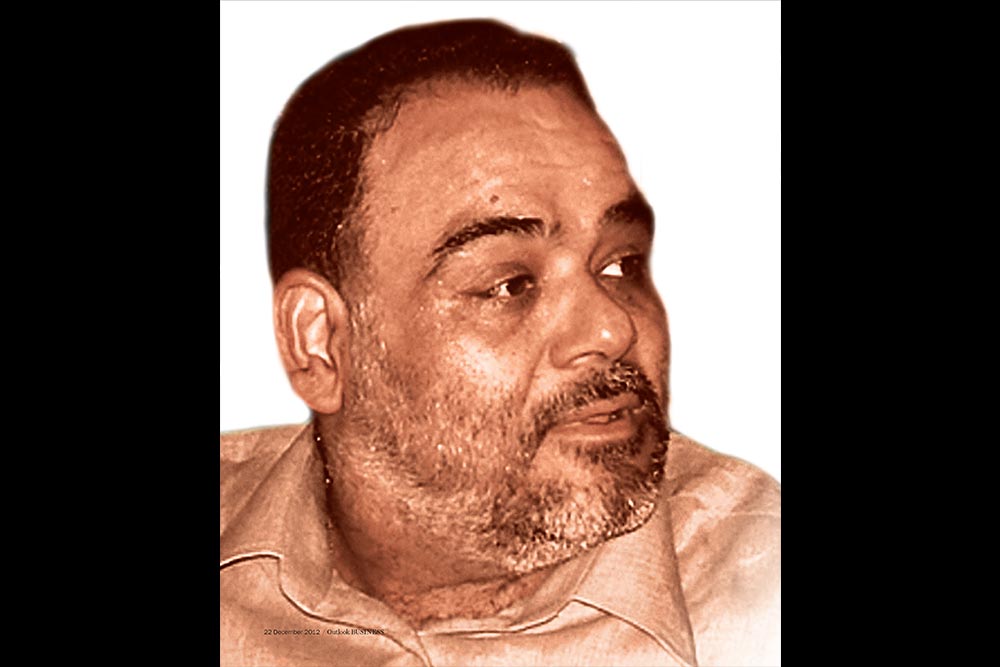

“This” is the untimely death of liquor baron Gurpreet “Ponty” Chadha and his younger brother Hardeep in a hail of bullets at their family’s farmhouse outside Delhi on November 17. Who shot whom and why is still to be established but, already, questions are being raised about the future of the sprawling liquor, film and real estate empire Chadha carved out almost single-handedly. It was to allay such fears that Manpreet (Monty) Chadha and Rajinder Chadha, Ponty’s son and younger brother, respectively, issued half-page advertisements in major newspapers that spoke of continuing the “lineage and heritage of excellence”. The ad was taken out by Wave Inc, which houses Ponty’s wide business interests across the liquor and sugar businesses, real estate, film distribution and exhibition and education, among others (see: Portfolio extraordinare). “And the journey continues”, it stated.

Not everybody’s buying that. Just before Diwali, Ponty had launched a new commercial project, Wave Silver Tower, at Sector 18, Noida, where a 13-storeyed building is being planned on a 3,000-sq m plot. “You get me clearance from the Noida Authority for one small, single-floor building without provisioning for parking,” dares a broker. “Pontyji managed an entire 13-floor tower.”

That wasn’t all Pontyji managed. He had wrested control of about 80% of liquor distribution in Uttar Pradesh and those licences are coming up for renewal in March 2013. Already, his rivals in the distillery business are mentally calculating their gains — presuming that Monty will not be able to run a monopolistic setup like his father. His associates in Bollywood, too — Ponty’s interest in cinema ranged from building multiplexes to film distribution — are terming his death an irreparable loss.

In his death, Ponty made more headlines than he did in his lifetime. And this despite building up a business group worth Rs.2,500 crore (officially, that is; rivals and media reports proffer figures that range from Rs.6,000 crore to Rs.20,000 crore). This was a man who had the ear of top politicians and whose influence cut across party lines. He started off selling pakoras on the road in Moradabad. Just how did Ponty Chadha become a colossus in the murky world of business

and politics?

Small beginnings

With the threat of Partition looming, many Punjabi families left what was to become Pakistan to move to India. Ponty’s father, Kulwant Singh Chadha, was one such man who left Montgomery and moved to the Terai belt a few years before Independence. He finally settled in Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh, where he started a small snacks shop outside a country liquor outlet. By the late 1960s, Kulwant managed to get a country liquor licence of his own and started a wine shop at Moradabad’s Amroha Gate. Shortly after, Kulwant also started a sugarcane crushing unit; some years later Ponty, who dropped out of school after class 10, joined his father.

To get a liquor store licence in Uttar Pradesh in the 1970s, the applicant had to have a minimum bank balance of Rs.1 lakh and even then would not get a licence for more than 10 shops. That’s when the Chadha family came into the business — Kulwant, his brothers, his sons and daughters, all were roped in. The Chadhas followed the peti system where the store owner retails the distributor’s stock as a partner and gets 5-10% of the revenue. Liquor is a recession-proof, all-cash business. With so many licences under their belt, the Chadhas were in the money very soon and expanded into the paper business in the late 1980s. Ponty’s younger brother Hardeep was put in charge of this business.

Now that hobnobbing with the monied was a regular affair, Ponty decided to diversify into more mainstream businesses. Ponty, his older associates say, didn’t like the family to be known as “sharaab bechne wale” and in 1993, they moved from Moradabad to Delhi. The Chadha Group, now renamed a more chic Wave Inc, got into real estate first, launching a project in Moradabad; some years later, it was to give Lucknow its first mall. Wave also grew inorganically, taking over Coca Cola’s bottling unit in Amritsar (there’s a family connection here: Monty Chadha is married to the bottler Gurdeep Khandhari’s daughter). Now it was a diversified group with interests in distilleries, sugar, paper, real estate and film distribution, and its political connections had also started around that time.

Cutting across

“My family has been building connections for two generations and we know everyone. We know people in every political party, we never suffer when the government changes.” This audacious statement can be found in an essay on Delhi that British Indian writer Rana Dasgupta wrote for Granta in 2009. The speaker was identified only as MC but it doesn’t take too long to figure out this is Ponty’s son, Monty. And he was only stating what is common knowledge.

Ponty’s largesse extended to all political parties in need. A favourite of the Mulayam Singh Yadav government between 2003 and 2007, he nonetheless financed Mayawati’s campaign alongside. And when the Samajwadi Party came back to power, he wooed them as well with consummate ease. Ponty, in fact, got along well practically with the entire political elite of North India. The Congress and Shiromani Akali Dal favoured him in Punjab during their respective terms and his influence in the state was impressive. When his Scorpio was stolen in Chandigarh, police teams worked overtime, rounding up virtually anyone with a similar vehicle — the car was recovered in less than a day. His relations with BJP are also not a secret anymore — in Uttarakhand, BJP’s Sukhdev Singh Namdhari (the former head of the Uttarakhand Minority Commission and now a key suspect in the brothers’ deaths) is said to have acted as frontman for Ponty’s mining interests in the state for several years.

But the first politician to shower favours on Ponty was veteran Congressman, ND Tiwari. When Tiwari became chief minister of Uttaranchal in 2002, he awarded Ponty a contract to mine stones and sand from the state. Royalty was paid on each truckload, a system that left immense scope for under-declaration. The next year, Mulayam came to power in UP and Ponty benefited there as well. Work on Wave’s Hi Tech City started in Ghaziabad during this time, a 4,800-acre project that’s said to be India’ biggest housing project.

His connections made it possible for him to make money from almost anything — mining, real estate or even a government-aided nutrition programme. The anganwadi meal scheme needed a supplier since Modern Foods had backed out after being taken over by Hindustan Lever. Contracts until then had been given to small and cooperative or public companies to supply flour, sugar and edible oil to anganwadis to make panjiri. Now, the state government allegedly tweaked the conditions so Ponty’s company True Value Food could be awarded the contract. In 2007, the party in power changed but Ponty’s contract continued even under Mayawati. And in September 2012, the current Akhilesh Yadav administration, too, tailormade conditions to award the panjiri contract to True Value Food. Only companies with manufacturing facilities in the state and minimum annual turnover of Rs.25 crore were declared eligible for the three-year, Rs.9,000-crore contract and Ponty’s company was selected from the technical bids. The case is now before the Lucknow bench

of the Allahabad high court after a rival company challenged the tendering process.

But the mother of all favours came in 2007. Having funded Mayawati’s campaign, Ponty was in a position to ask for special concessions — and get them. Accordingly, in 2008, the Bahujan Samaj Party consolidated the state’s excise zones into four zones and gave Ponty exclusive right of wholesale liquor distribution in the state; he was also given retail distribution rights in the largest of the four zones. With such a monopoly, he could now dictate terms both at the backend (UP has 54 distilleries) as well as the frontend (around 18,000 shops across 75 districts). It is the norm to pay more than the MRP at government-owned liquor stores in UP — the premium is referred to as ‘Maya prasad’ or ‘Ponty tax’, depending on whom you ask. “Rs.300 overcharged on a case would fetch Rs.100 each for Ponty, the retailer and the BSP. They must have made Rs.300 crore each month by doing this,” says an executive from a rival distillery.

Maya’s munificence continued and Ponty got prime land in Noida and a stake in five sugar mills — all for a pittance, naturally. It is said Ponty took advice from a battery of lawyers before going ahead with the sugar mills deals. First, the state government leased the mills to the Uttar Pradesh State Sugar Corporation. The company then sold the mills below the reserve price to Ponty’s companies (directly or indirectly controlled companies). The Comptroller & Auditor General (CAG) has estimated the loss to the exchequer from this deal at Rs.1,200 crore; the matter has now been referred to the Lokayukta. The CAG report states that Wave Industries, SR Buildicon, Giriasho Company, Namrata Marketing, Neelgiri Foods and Trikal Foods & Agro Products were linked to each other through common shareholders and directors and many of these submitted bank drafts with consecutive serial numbers, prepared on the same date from the same branch of the same bank.

Larger than life

For someone who grew his empire through sheer grit and guanxi, the 55-year-old Ponty had a sterling reputation for straight dealing. “He was a very honest man, especially clear in his mind,” says film producer Boney Kapoor, whose films Wanted, No Entry and Ishaqzadey were distributed by Ponty’s company Ginni Arts. “After watching Wanted, he said, ‘Boneyji, yeh movie toh hit hogi. Koi nahin rok sakta.’ No distributor usually makes such a forthright statement.” Pinnacle Property’s Aggarwal swears by Ponty’s commitment and quality of work in the real estate business. “Everyone in the chain got their commissions and dues on time. His projects were never delayed over six months.” An intensely private man who was perhaps conscious of his disability — he had lost one arm and part of the other hand in an accident as a youth — Ponty’s business was nonetheless a one-man show. Who he obliged, how he networked, perhaps even the sum of his business interests — all those secrets may have gone with him.