Footloose. Wanderer. Rebel. I wonder if these adjectives truly define me. But I do love living life the way I believe it should be lived. Today, when I look back, boy, it does seem like it has been one hell of a ride!

My early memories of childhood are from those days in Deutschland. I was eight when we moved to Germany for a year, when dad was overseeing an alliance with Eicher, a German tractor manufacturer. That one year was a big revelation. I got to see a whole new environment and a completely different culture. Living in a small village, and the thrill of cycling down the roads was so much fun. Call it destiny or fate, but I was besotted by wheels. As a kid, I barely wanted to walk, and instead loved zipping around on a tricycle even at home. By the time we were living in Germany, bicycle was like an obsession and, for me, it stood for freedom, and in Germany I loved it when those big trucks used to halt and make way for a little chap on a cycle. The passion for wheels only kept intensifying with age, though I never knew that one day I would end up running a motorbike company!

***

Honestly, motorcycles were never on my radar in my early teens. On occasions, I would hear dad mention Royal Enfield, but I never really understood what it was till I turned 17. I vividly remember the day I came back home after completing my boarding school. There was this gleaming chrome red motorcycle parked in the garage. It was love at first sight. I just wanted to get my hands on that lovely piece of metal, then known as Royal Enfield Machismo. But my dad, who used to ride it then, was like: “Hey kid, don’t you dream of riding it till you are 18!” But the rebel that I was, I would always sneak out with it for a quick ride. A year later, I got to ride it legally to my college every day.

My first long ride was with a couple of friends — from Delhi to Dehradun, and then to Mussoorie. It was so much fun. What made those excursions enjoyable was chilling out with friends at roadside dhabas, chatting with fellow travellers. The teaming up of man and machine kept growing on me — the distinct thump of the bulky beast was shaping my personality. The adrenalin rush was inescapable — so much so that I even rode down on a red Bullet to my wedding venue!

But my most memorable road trip was at 21, when dad sent me to Europe to interact with importers of Royal Enfield motorcycles. My first stop was the UK and, after a couple of months, I went to Switzerland to meet another importer. Boy, this guy was doing some amazing stuff with bikes. His passion was so addictive that I ended up working with him as a mechanic in his garage! And it’s here that I got my first taste of long-distance motorcycling — on a month-and-a-half-long sojourn that turned me into a nomad. I borrowed a Royal Enfield bike and tucked into my rucksack a sleeping bag, a tent and a couple of essentials. Off I went touring Europe — traversing across six different countries, pitching tents wherever I wanted to, meeting strangers at cafes and engaging in conversations even without knowing their local language.

While riding down to college was a different feeling, motorcycling with no real destination in mind is like nirvana. When there’s no place to go, you tend to enjoy the journey that much more. You lose sight of time, space and priorities – a spiritual journey of a different kind. For the first time, I began to appreciate the magic of wanderlust. From that day till now, those memories have been my best.

***

What made life easy for me was also the relaxed atmosphere at home. Though we were into business, dad never brought work to the dinner table, and nor was I groomed or made to feel that I would eventually be taking over. Guess, my folks were smart! They knew had they thrust it upon me, I would have said a big “No, thank you”.

While there was always some talk around me doing an MBA, I opted for economics from St. Stephens. I don’t know at what point my biking interludes unwittingly drew me into my family business. Somewhere I feel my parents also kind of nudged me in the right direction. At Royal Enfield’s Chennai facility, I used to visit factories of our suppliers and saw how castings were made. I was 25 when I got bitten by this bug of “how do things work.” The practical application of engineering kind of excited me. Come to think of it, you find your true calling when something piques your curiosity, and you can’t help but chase it.

As I was warming up to the idea of engineering, there was a hitch — institutes in India weren’t willing to admit you unless you started from scratch. Clearly, pursuing four years of engineering as an undergrad wasn’t my cup of tea. So, I tried in the US and the UK, and found a couple of universities where one could do a post-graduation diploma. That’s how I landed up at Cranfield University to pursue my diploma in mechanical and aeronautical engineering. It was also the best time of my life in terms of learning since I was thrown into the absolute deep end.

As I was warming up to the idea of engineering, there was a hitch — institutes in India weren’t willing to admit you unless you started from scratch. Clearly, pursuing four years of engineering as an undergrad wasn’t my cup of tea. So, I tried in the US and the UK, and found a couple of universities where one could do a post-graduation diploma. That’s how I landed up at Cranfield University to pursue my diploma in mechanical and aeronautical engineering. It was also the best time of my life in terms of learning since I was thrown into the absolute deep end.

I studied with an eclectic bunch of people – some who had done their bachelor’s degree, and some who were seeking a refresher course. Though I hadn’t studied physics in my 11th and 12th, I was good at Math. The classes on aerodynamics were the really tough ones. Thankfully, I had friends who helped me understand the concepts well. It was an interesting combination — people with degrees who had never worked in an engineering environment and me who knew the nuts and bolts without having studied the mechanical stuff. I understood stuff at a physical level but grappled with the concepts, while my friends were good at the concepts but had never seen parts and gears, except on paper. Come to think of it, it’s like a mechanic at a roadside garage who is not an engineer but understands, at a certain level, what most engineers don’t.

While the first term was challenging, I did well in my second and third term. Finally, I also ended up pursuing masters in automotive engineering from the University of Leeds, UK.

***

I was back in India in 1999 — two years after my father had stepped down as the chairman and CEO by handing over the reins of the group to professional managers led by Subodh Bhargava. That meant a family member couldn’t be just be airdropped at the top, so I had to earn my stripes.

I did a stint at the marketing division of Eicher Tractors for a year — it was also an opportunity to explore the rural market. Around that time, I created the GIS and digital maps division. Much before the world of Google Maps, Eicher had first forayed into maps in 1996, with a hardcopy publication of Delhi’s map. Building on the accuracy and detail we had managed, we entered the GIS mapping space in 2000. The services were run on servers using specialised software and a qualified team of GIS professionals.

It wasn’t long before I was given the option of moving to other group businesses, except Royal Enfield, which was in a mess and on the verge of being sold off. I was clear that I didn’t want to get into the trucks and tractors businesses and, instead, felt motorcycles would be right up my alley. The board agreed to give me a chance. I guess it was not because of their confidence in me, but because the business was doing so badly it could hardly get any worse! Incidentally, Royal Enfield had a rich history as its British parent, Enfield Cycle Co, had made the brand popular during World War II. But in 1971, the parent pulled the plug on the business. But its 350cc iconic Bullet was still assembled in India by Madras Motor Company. In 1994, the business became part of Eicher Motors after a merger.

It wasn’t long before I was given the option of moving to other group businesses, except Royal Enfield, which was in a mess and on the verge of being sold off. I was clear that I didn’t want to get into the trucks and tractors businesses and, instead, felt motorcycles would be right up my alley. The board agreed to give me a chance. I guess it was not because of their confidence in me, but because the business was doing so badly it could hardly get any worse! Incidentally, Royal Enfield had a rich history as its British parent, Enfield Cycle Co, had made the brand popular during World War II. But in 1971, the parent pulled the plug on the business. But its 350cc iconic Bullet was still assembled in India by Madras Motor Company. In 1994, the business became part of Eicher Motors after a merger.

But when I took over, I was naïve to assume that things weren’t really as bad. I knew nothing about the business and my knowledge was limited to motorcycling and engineering. I thought: how tough could it be to design a new motorcycle and stem the bleed? Though the bike had a cult following, complaints around engine seizure, electrical failure and oil leakage was common. But it wasn’t just a product problem but a lethal concoction of HR, working capital and labour issues that had plagued the business as well. I found myself again at the deep end.

I took charge as chief executive at Royal Enfield and started spending time with everyone. We let go of a lot of people, and there had been this bizarre motley crew running the show earlier. There were no engineering or marketing people at the top, and those who were had been dispatched to run other parts of the business. Dealers had been unhappy as bikes had transit damage with deep gashes, seats ripped, paint peeled off. The reaction at the company ranged from, “we will look into the matter” to “nothing can be done.” I had to tell the latter folks, “Sorry, we don’t need you anymore.”

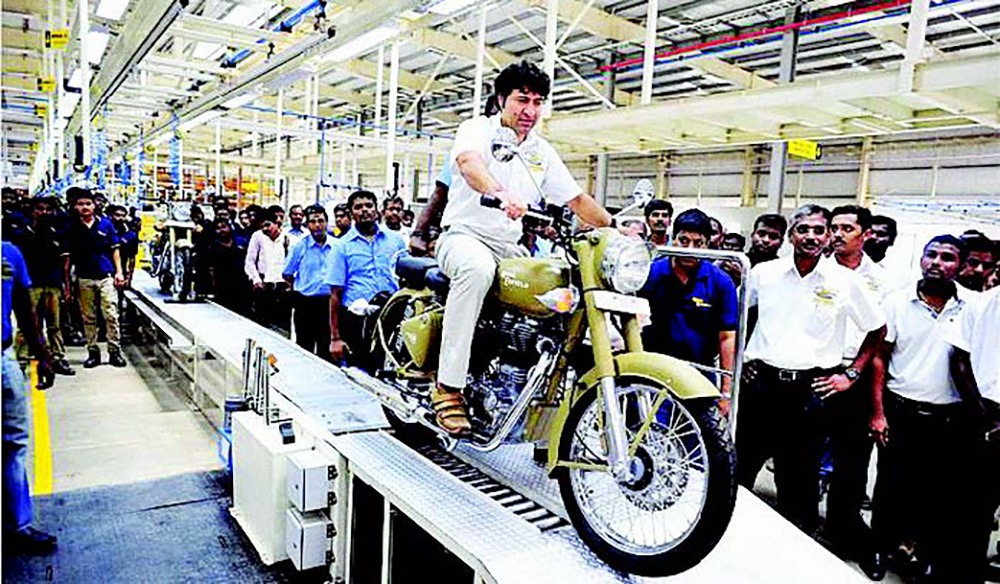

We made some course corrections. We changed the way goods were being shipped – from straw packing, we shifted to Styrofoam. Our transportation cost went up a bit but we were building dealer and customer confidence. Importantly, we created a new look product with a new engine and altered the gear position. To produce the vibration and the thump of the old engine, we consulted international experts to ensure that the bike produced the maximum rhythmic vibration possible, and the thump remained close to the original. By 2004, we had stemmed the bleed with the company selling about 25,000 bikes every year. That year, I also took over as the group chief operating officer and, incidentally, it was one of the most crucial phases of my life.

***

My condition for taking on the mantle was a free hand to do what I thought was important. Our group was then into 15 different businesses, including garments, shoes and food products, most of which were sub-par. Though it sounds bizarre, the businesses were an outcome of rigid forex controls. Since we were importing kits from Japan for the trucks business it meant that as a net forex spender, we also had to earn as much forex. I guess it was the toughest decision of my life when, in 2005, we decided to sell 13 businesses.

The senior management team worked over six months on a roadmap along with BCG. It was a tricky time because one wasn’t sure whether it was the right strategy. The biggest decision was to sell our tractor business – started by my grandfather and built by my father. I would be lying if I said I wasn’t deeply emotional about it as well. But the reality was the business had run its course. While at first dad felt we should be retaining that business, my point was it was more historic and not futuristic. I spent a lot of time with my parents deliberating over the revamp; they gave me all the counsel but never told me what to do.

My dad’s advice was: “You are out there. You need to figure out what’s right and what’s wrong. If you think selling tractors is the right move, then that’s what you should do because you have to take the decision.” That’s super rare in India, a family business where the scion gets an absolute free hand, especially in a business into which the patriarch has put his sweat and blood. In fact, a lot of my peers would often complain about their dads breathing down their neck. If you have always been told what to do, by the time you hit 55, you are jaded and spent. Thankfully, I had none of those shackles.

Though I did question myself, whether retaining the motorcycles business was merely because I was deeply passionate about it, which some in the management did feel was the case!

The decision to cut the cord was upsetting for everybody, including the nucleus that my father had created. But what had happened was, at some level, a bit of rot had crept in. An amazing people-centric culture had over the years turned bureaucratic with no one really held accountable. My dad, usually, never let go of people. If someone was not working well, he would work around it. But after he had left, it had become sort of an unwritten rule that we won’t sack people. That’s when I realised that we had to keep moving with the times. In any case, a lot of the senior management team went off with the tractor business. It was heart-wrenching, but we had to let go. In retrospect, I was not exactly happy about it, but I have no regrets either. I always believed there was an enormous economic reason for the motorcycles business to thrive.

***

Royal Enfield had a strong brand recall and, even though it had been scarred a bit, the gross margin was great. It was just that we weren’t selling enough of them. I felt that it was better to build a business whose gross margin was better than those that offer larger scale but wafer-thin margin. I again took a contrarian approach. I believed that if we hit 100,000 units a year — we were at 20,000+ units— fixed cost as percentage of sales would go down, we would get better pricing from suppliers, and increased pricing power by reducing discounts. So, all three levers were going to change.

But the bigger change was going to be the perception around the brand. The big ‘Aha’ moment was when we set up our first store at Adyar which connects to Besant Nagar beach in Chennai. We chose that location because it was the favourite weekend joint for youngsters who rode down the road to the beach. We set up this little store with our Thunderbird and Electra bikes with gorgeous Royal Enfield flags flying atop. We just hung around the store waiting for customers to come in. I remember one moment where I saw these five young lads on their little 100cc bikes going to the beach and they all zipped by but soon turned around and entered the store. One guy walked up to me and asked if it was a Royal Enfield store. I said, “Yes, don’t you know about the bikes?” He replied they did know the bikes but didn’t know they were from Royal Enfield. That was an insight that stuck with me – the look of a shop mattered to those buying a motorcycle. Technically, it shouldn’t matter but it does. The earlier perception of Royal Enfield was different, “that the bike is not for me, it's for my uncle.” Making our stores look cool and funky changed that image.

I got some of these branding concepts from my mom who has been running Good Earth for the past 22 years. She would say, “I don’t want to grow the business and instead do something really special.” If you keep growing by just adding stores and moving to new geographies, “growth” becomes the company. While she didn’t want to stay small, she wanted to do beautiful things. She does things with great passion and interest, and has created a unique positioning for the brand with exotic craft stuff. That’s the kind of learning I have absorbed over the years that growth alone doesn’t have to be the driver. You can take it to an experiential zone like we did with Royal Enfield. It’s really the ride, the ecosystem and the community of bikers that have got Royal Enfield where it is today. It’s not about mindless growth.

Usually, when brands enter a new market, the general idea is to build a plant, create a strong distribution network and pump in products. That’s not how I want to do it. I don’t care about the next quarter or two years, instead I look at a business from 10 or 15-year horizon and what the right thing to do is. We have put up really nice stores at Sao Paulo, Bangkok and Jakarta to let people come and experience what Royal Enfield stands for and, if they love it, the business will grow. We are not in a hurry to put up 30 stores because the moment you find no one is buying your product, you start discounting the price. That does more damage to the brand and works at cross-purpose of what you want to achieve.

***

I love being a contrarian. Maybe it’s because I was the second child, or it could be because I am left-handed. I always heard that such children tend to be different always. It’s a trait I follow in my business – if the majority said this is the way to go, I would naturally go the other way, even if it means wearing casuals instead of a suit. I remember once at a party in Delhi everyone was wearing identical clothes – black trousers, stiff shirts, blazers, black shoes and smoking cigars. As I walked in, someone called out to me saying, “Siddharth, tu toh businessman jaisa nahi lagta,” and my answer was, “Dude, it is hot, why should I wear a suit? I don’t get it and if don’t get it, I don’t do it.” It has stayed with me — be it in life or in business.

But it’s not that I haven’t made mistakes. Our joint venture with US-based Polaris Industries was a huge one, which consumed a lot of time, money and effort. We entered into a joint venture in 2012 and three years later rolled out Multix, which was the country’s first personal utility vehicle. There was a lot of interest initially, but the subsequent sales were lower than expectation. Money-wise, we lost quite a bit (around Rs. 3 billion), but the real mistake was we tried doing too many new things. The most difficult thing in business and in life is the ability to say, “no, this doesn’t work”, and that can be a big source of inner peace.

When you spend a lot of time thinking over something, at some point, clarity does emerge. For me, it was when I realised that “less is more.” That meant, let’s do one thing and do that exceptionally well, and not try to do too many things. If Royal Enfield is destined to become the biggest motorcycle company in the world, it will find that path. If its path is somewhat different, it will find that path and of course we will navigate it to some extent. So that’s been an enormous learning and philosophy in life – don’t force the pace.

***

To be honest, I am not very ambitious. My ambition first was to not lose money, and we achieved that. After that, it’s been “let's do something really fun”. For me, this journey has always been about really enjoying myself, making it worthwhile for those working with us, our customers and even our dealers. If you are having a good time while doing all of this, as opposed to just making more money, that's worth a life. It wasn't that we always wanted to be the biggest motorcycle company in the world. The motivation began with let’s hit 100,000 a year because at one point we were clocking sales of only 8,000-10,000 units. Now, we have crossed 500,000 units. Two decades ago, I wouldn’t have imagined that we would come this far.

Going ahead, I believe that the company needs to be run differently. While I enjoyed being at the helm for a good part of the past two decades, it’s important to align the company with the mega trends of the future such as digitisation, electrification, connectivity and shared mobility. I believe I can serve the company better by playing a role different from the CEO. That’s the reason I handed the baton over to Vinod.

***

In my 20-odd years at the company, people have appreciated the brand from different parts of the world. It was sometime around in 2002, Nick Sanders, a wild intrepid traveller and the first person to circumnavigate the world on a Royal Enfield, rang me up when I was in Chennai. He asked, “Sid are you in office, I am in Chennai.” I said, “Come over for a cup of coffee.” When he came over, I asked him what brought him to Chennai of all the places. He said he was taking a group of bikers on a world tour and was doing a recce for the trip! I said, “Äre you serious and where are you coming from now?” He replied, “I was going on top of the Himalayas, but since I hadn’t seen you in a while, I thought I would do a little detour to Madras and say hi to you!” After the coffee, he said, “Ït was lovely meeting you. Now, I am on my way back to England!” That’s the kind of spirit and people that inspire me. It’s not big businessmen, but individuals who do stuff because they found their calling in life. I believe I have done that as well. The fact that, in my own small way, I have preserved a piece of India’s culture and craft by keeping the world’s oldest iconic motorcycle brand alive. That gives me enormous personal satisfaction. I can’t think of anything better that I could have done with my life.

Watch the video here.