Your neighbourhood kirana store is a toughie. It may not let it on, but food and grocery (F&G) retail in India is not an easy bout. Online and offline, the competition is intense and margins, wafer-thin. The biggies are consolidating. In 2015, Bharti group sold its Easyday chain to Kishore Biyani’s Future Group and so did Shoppers Stop, in 2017, when it handed over HyperCity. Last year, the Aditya Birla group sold More to Samara Capital and Amazon.

The giants may leave the ring, but a smaller, more resilient player is still standing — the Radhakishan Damani-owned DMart chain. It is one of the most profitable firms in F&G retail with a market cap of Rs.810 billion. According to a Morgan Stanley report, DMart’s stores generate more revenue/square foot than Walmart – $530 versus $450. The DMart success has been built, by its parent company Avenue Supermarts, on carefully crafted strategy and well-planned expansion.

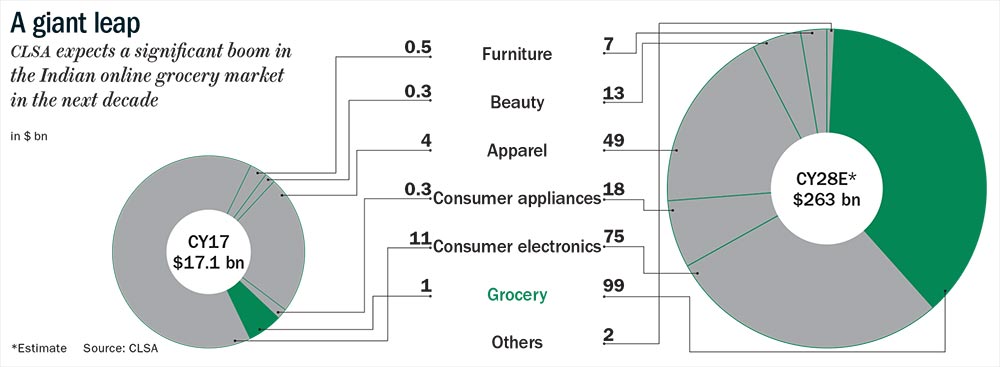

But the retail trade of today is not a business where you can sit pretty on your laurels. It is a fast-evolving market with varied delivery formats, all competing for a share of the consumer’s wallet. The new challengers that are turning on the heat are online supermarkets such as Bigbasket and Grofers. The e-grocers currently have a miniscule share of the F&G market, of less than 1%, but they are growing fast. Brokerage CLSA expects the e-grocery segment to grow to $99 billion over the next decade, which is an impressive leap from $1 billion in 2017! (See: A giant leap)

That’s probably one reason DMart started courting a new store format DMart Ready in 2017. In this new store format, customers can place their order online or through the app. They can then collect their purchases from the DMart Ready stores, which average 150-200 sq ft, or have it home-delivered for an additional charge. Today, there are more than 150 DMart Ready stores in Mumbai and Thane. “Our rough estimate suggests that these stores may account for 1% of DMart’s overall revenue in FY19,” states a Kotak Institutional Equities report.

It is a whole new experiment, but CEO Neville Noronha downplays it. Speaking exclusively to Outlook Business at DMart’s headquarters in Thane, Noronha says, “This is a long-term project and we will go slow as we have done traditionally, even in our brick and mortar business.” He understands quite well that he now runs a public-listed company, not a venture-funded firm that can absorb losses quarter after quarter to simply build consumer loyalty. He has to have a solid strategy, which will eventually pay off. “DMart Ready is in its pilot phase. We still have a lot to understand in this business, and that’s why we haven’t set any milestones or targets so far as growth is concerned,” he says. But what exactly is DMart Ready really trying to achieve?

Quick And Cheap

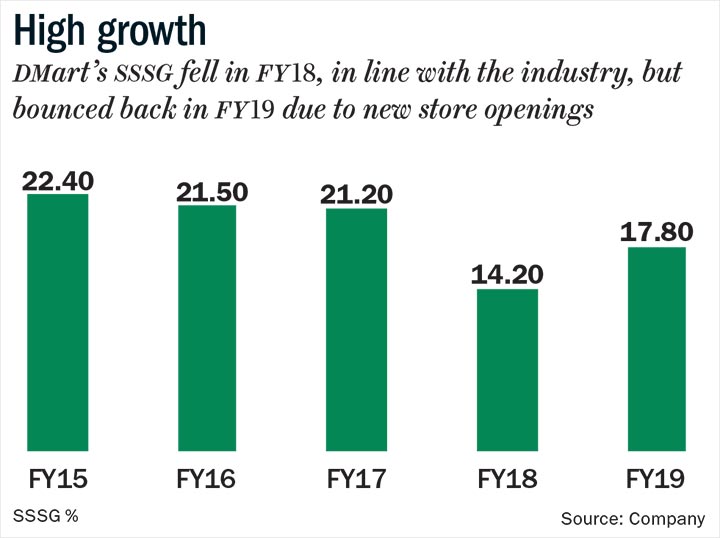

Clearly, the idea behind the stores is to provide convenience to customers, tap into the e-commerce category and address the issue of high real-estate cost in cities such as Mumbai. For instance, through smaller DMart Ready stores, the retail giant now has a presence in areas such as South Mumbai, where real estate prices are exorbitant. An equally important factor is that it helps the brand capitalise on the trust it has built through its offline outlets. The company reported same-store-sales growth (SSSG) of 14.2% in FY18 compared to its rivals Future Retail’s Big Bazaar and Trent’s Star Bazaar, who clocked 13.4% and 8.1% SSSG growth respectively. In FY19, DMart’s SSSG rose by 17.8% (See: High growth).

Even online, DMart has the edge of selling products cheaper than its counterparts. According to an Edelweiss Securities report, the competitive prices offered by DMart Ready are unmatched in the online retail space. Staples are priced 9% lower than the most expensive online platform; personal and home care, 15%; and discretionary basket is 14%. The prices offered by DMart at its Ready stores are similar to what it offers its offline customers.

Since DMart’s inception in 2002, with its first store in Powai (a suburb in Mumbai), it has successfully defended its USP of being the lowest-cost retailer in India. Its robust offline presence, with 176 stores across 11 states and one union territory, is courtesy its ‘Every Day Low Prices’ (EDLP) approach. “EDLP is a globally accepted practice followed by several large retailers. Our founder, Radhakishan Damani, set the direction for the company around this concept and idea,” says Noronha.

At the core of their competitive prices is their sourcing and inventory management model. “For instance, if they want to procure 100 brooms, then they don’t buy ten different brands. They buy one single brand, and hence end up getting a better price. Beyond a point, a customer is not concerned about the brand of a broom,” says Ankur Bisen, who leads the retail division of Technopak Advisors. More importantly, they stock lesser SKUs compared with others. The logic is to keep fewer brands that fly off the shelf quickly so that inventory carrying costs are lower — DMart has superior inventory cycle of 34 days, compared to Future Retail’s 120 days. This enables them to make quicker payments to suppliers and vendors to extract higher discounts. These discounts from the supplier network are passed on to customers, gaining their loyalty and perpetuating this virtuous cycle.

Besides, DMart saves on operating expenses by buying real estate, rather than renting it. “None of their stores are in shopping malls. When you are opening stores in the standalone format, you can customise them as per your requirement. In addition, a part of the expenses, such as mall management cost and rent, are completely eliminated,” says Amnish Aggarwal, head of research at Prabhudas Lilladher. That said, owning real estate cannot be a long-term strategy, agrees the management at DMart. The company is now looking at the option of long-term lease (25-30 years), which it has opted for, at some of the newer locations.

Over FY15-19, DMart’s sales and profit have grown at a CAGR of 23.46% and 33.64% respectively. Its average sales/square feet of Rs.32,719 is better than its domestic counterparts’ — Big Bazaar’s (Rs.14,514) and Reliance Retail’s (grocery sales of Rs.25,751). Despite the heavy discounts offered, its margins are higher than that of global players. The company’s Ebitda margin at 9% is better than Walmart’s (5.6%) and Tesco’s (2.3%). It is also better in comparison to domestic competitors, Spencer’s (0.08%) and Future Retail (4.5%).

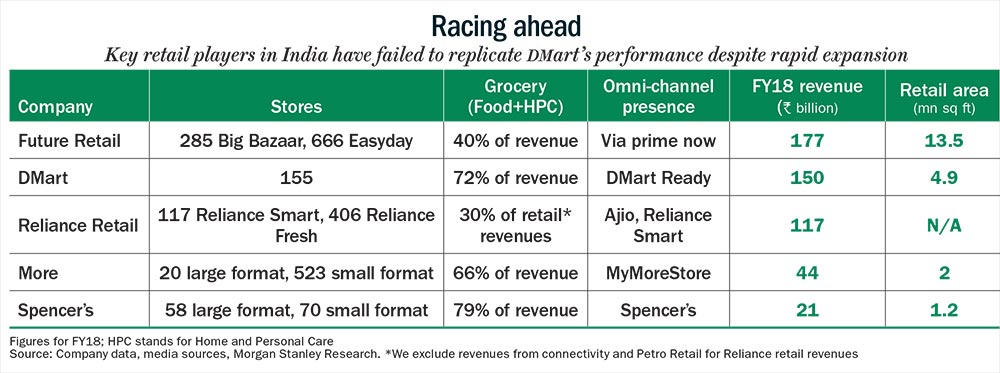

But there is more to their success than low prices. “A lot of patience, detailing and deep insight went into building the DMart business model,” says Noronha. Patience has indeed guided their growth. Other retailers in India expanded at a rapid pace, seeing a massive opportunity ahead — organised retail accounts for just 9% of the overall pie (See: Racing ahead). But DMart has chosen to go slow.

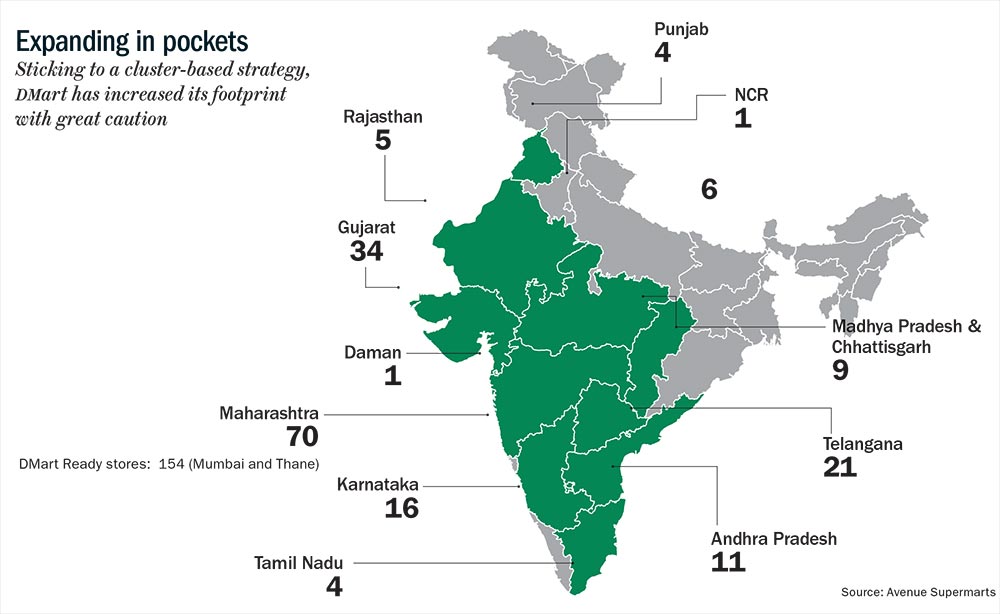

This is because the company believes in a cluster-based approach, which has been one of the bedrocks of the retail giant’s success story. However, the strategy was born out of necessity, not choice. “Mr Damani would never agree to fund that expansion rapidly without proof of profitable scale closer home. So in a way, our own internal limitations made us stick around closer to headquarters. In hindsight, clustering now looks like a great strategy, but it emerged out of a handicap,” says Noronha. A majority of its stores — 59% — are located in Maharashtra and Gujarat (See: Expanding in pockets).

A new store location is based on parameters such as population density, potential growth of the local population and economy, area development potential and estimated spending power of the population. The cluster-based strategy has helped the company sharpen its supply chain. “When you are working in a micro market or cluster, your sourcing efficiency is better, because you are buying and selling in one particular location. If you have 100 stores in different states, then you are not going to be efficient in any way, a mistake that most retail players make. But Avenue Supermarts’ strategy since day one was to develop state-by-state and city-by-city. That’s why their numbers look good, and they are valued so highly,” says Harminder Sahni, founder of Wazir Advisors.

There is also room for diving deep in the pockets where the company has a good presence. “We see huge opportunity for DMart even in Maharashtra and Gujarat, which are the company’s home states. DMart accounts for mere 5-6% of the overall grocery market,” says Abneesh Roy, senior vice-president at Edelweiss Securities. To help with the expansion, the company has approved a qualified institutional placement (QIP) of 25 million equity shares to raise Rs.31 billion.

Online Fighters

India spends around $500 billion on grocery every year, and existing e-grocers such as Bigbasket and Grofers are fighting for their share with the help of venture funds. So far in 2019, Bigbasket has raised $150 million and Grofers, $260 million, respectively. Interest in this segment is being “led by horizontal e-tailers Amazon/Flipkart training their sights on it, entry by food O2O player Swiggy and brick-and-mortar chains launching/experimenting with omnichannel”, according to CLSA Securities.

Amazon’s More buy is, reportedly, to integrate its online and offline businesses. In India, the US giant has been testing the waters in offline retail. In September 2017, it picked up 5% stake in Shoppers Stop. Experts believe Amazon teamed up to buy More for two reasons. “First, to try and reduce delivery cost. Second, to acquire important data points from More stores, on customer preferences in different cities and favourable price points,” says Satish Meena, senior forecast analyst at Forrester Research.

Despite the biggies in the fray, funding for e-grocery start-ups continues to be strong, because they have been able to scale up swiftly. Online grocer Grofers reduced its loss marginally, to Rs.2.58 billion, in FY18. This was due to a substantial increase in revenue from Rs.340 million to Rs.530 million, according to research platform Veratech. Even Bigbasket’s performance has improved, with its revenue rising 34% to Rs.16.06 billion in FY18 and the net loss falling 53% to Rs.3.1 billion. Bigbasket has been able to attract customers led by a combination of discounts, cashback and private labels such as Fresho and GoodDiet. According to CLSA, private labels make up around 30-40% of SKUs and revenue for Bigbasket and Grofers, and hold the key to bargaining with FMCG firms.

So far, DMart has not really focused on its private label business. The large amount of money needed, to launch and market it, has deterred the prudent company. But now, DMart intends to use its Ready stores to sell its private label ‘Reflect’, which is for kitchen cleaning products. Although Noronha refuses to divulge his plans, analysts believe that the company will continue to add an array of products to this format and scale up. “We expect a more big-bang expansion only once the business model stabilises in Mumbai,” states Garima Mishra of Kotak Institutional Equities in her report. Just like most big consumer brands, DMart is likely to use its Ready stores as a testing ground for private labels. This will be an inexpensive route since there is no risk of inventory pile-up across stores.

DMart Ready also lags Bigbasket in fresh produce. “Bigbasket has positioned itself well in the online ordering segment. Our channel checks indicate that off-take of fresh category products such as fruits and vegetables is very low in DMart’s Ready format,” mentions the Edelweiss Securities report. Bigbasket’s performance also rides on its high marketing spend.

The online grocer also offers subscription programmes, Express and slotted delivery, and ‘no minimum order’ service to increase the stickiness of customers. DMart Ready’s minimum order value of Rs.1,000, on the other hand, could keep customers away. It needs high volume for profitability, according to analysts at Edelweiss Securities. After examining six DMart Ready stores, they state that the management should consider relaxing its minimum order value rule or breaking even will not be easy. And the Ready stores that get 10 or less orders per day, at Rs.1,000 to Rs.1,800 per order, are posting negative margins.

Most importantly, e-tailers have lesser infrastructure cost on the operational side. Bigbasket’s co-founder, Abhinay Choudhari says, “We typically have only one or two distribution centres in a city, which means we have just one or two inventory holding locations. Compared to this, any offline player has multiple stores in the city.” Bigbasket’s warehouse capex is around Rs.50 million to Rs.150 million.

There are two sides to this story though. On paper, it might seem that an offline retail business model such as DMart is expensive because of the cost of real estate and large staff, which an e-grocer doesn’t have to bear. But there are other costs. “Cost has different interpretations. For example, an offline retailer may have a high rental, which an online retailer won’t have. But e-grocers have higher marketing cost, which an offline player doesn’t have to incur. E-grocers also have a higher cost of delivery, while offline players need to invest in training employees and have a higher payroll cost,” says Bisen.

Choudhari agrees that online players incur delivery cost, while an offline player has rental cost. “That’s why, when these offline players enter the online space, they offer click-and-pick service so that they end up saving delivery cost,” explains Choudhari. He adds that the biggest cost for Bigbasket is delivery, followed by warehousing expense. Interestingly, Bigbasket, too, is implementing a model similar to DMart Ready. The online retailer introduced pick-up kiosks last October, and Grofers is following suit through partnerships with kirana stores to sell its private labels.

On their part, e-tailers are cognisant of several ‘offline advantages’. An HSBC Global survey reveals that brick-and-mortar stores are a draw for their fresh produce and they also support impulse shopping. An offline store also enjoys greater customer trust, compared to an online platform. That’s what makes Ready a snug fit as it complements DMart’s offline presence perfectly. “DMart Ready stores already offer the convenience of online shopping, so we believe pure-play online grocery operators, which have smaller ticket sizes and high delivery costs, are not a sustainable threat to DMart,” adds the earlier cited survey.

Big Daddy

The real threat for DMart might come when Reliance Retail enters the e-grocery segment. When that happens, DMart will need a bolder approach. “If DMart Ready expands the way it is, it won’t be profitable. They will have to make free deliveries and increase offerings in the fresh and frozen category.” says Roy. While DMart has been able to scale up with a prudent strategy avoiding big cash burn, the entry of a player such as Reliance may put them in a spot.

It’s highly unlikely that Reliance will be a pushover with its deep pockets. Currently, Reliance Industries — the parent company of Reliance Retail — has cash and cash equivalents of Rs.1,330.27 billion compared to Rs.780.63 billion in FY18. With its long-standing ambition of becoming India’s number one retailer, it will surely use the pricing weapon to allure customers and build its online presence.

Analysts bet the stage is now set for Reliance to disrupt the retail market. Forrester Research’s Meena says, “Earlier, Biyani tried to go online and didn’t succeed. But Reliance can make use of their offline stores and strong brand presence. They also have the firepower of a healthy balance sheet so they can sell at a discounted price.” Not to be left behind, Amazon, too, can kick off a pricing war with the integration of its offline and online businesses. Ultimately, you can’t have five grocers catering to one household, adds Meena. Whoever provides the best price and customer experience will survive, and others will have to make way through consolidation.

“Bahut kaam karna padta hai retail mein!” says Noronha, playfully, when asked about the challenges DMart faces in the future. Recollecting the past hurdles, he adds, “Too many, in fact, but no single one will hurt you too much. The sheer number of issues is overwhelming.”

With a strong brand, large scale and attractive margins in a sector where costs continue to mount, DMart has been a consistent outperformer. As things stand, it hasn’t compromised on its core principle of calibrated expansion which helped it create shareholder value. It helped, then, that competition fell prey to breakneck expansion and could not get their business model right. With a well-established offline presence and a foot in online, DMart is ready to fight the new-age retail battle. This time though, the stakes are higher and competition, mightier and possibly wiser.

Just one email a week

Just one email a week