On March 31, 2021, Tarun Mehta finally came good on his promise made to Pawan Munjal in 2017 that the chairman and CEO of Hero MotoCorp would be his first customer when Ather Energy enters New Delhi with its electric scooter. “Unfortunately, Munjal couldn’t ride it because of lockdown restrictions. But he was excited about the design and was particularly fascinated by the IoT dashboard and spent 20 minutes discussing it,” Mehta, co-founder of Ather Energy, tells Outlook Business.

In some sense, it was Mehta’s guru dakshina to a mentor who had not only guided the founders, including Swapnil Jain, in their journey but also ended up funding Ather through Hero MotoCorp in a Series B round five years ago.

Mehta remembers meeting Munjal starry-eyed. “He was running one of the world’s biggest two-wheeler businesses but was candid: ‘The reality is we don’t know much about electric today and I personally think it is going to be massive. I think the industry will wake up to it in the next five years and a lot of stuff is going to change’,” recalls Mehta.

Although Hero went on to own a significant minority stake (35%) by investing Rs. 5 billion in Ather, there is an arm’s length distance between the two. “When you bring on a partner, you either become more like them or the complementary nature of your businesses kicks in, so there is learning on both sides,” explains the 31-year-old.

The Bengaluru-based start-up, which came to life in 2015 after being incubated at IIT-Madras, had showcased its first prototype, S340, at start-up fest Surge 2016 held in Bengaluru. But, after several iterations, it has ended up getting rave reviews for its ready-to-roll 450x model that boasts a top speed of 80 kmph with the ability to fast charge at one km/minute. “It’s a terrific scooter and also the fastest in its category. If you race it against a gasoline version, the 450x will have better acceleration. By offering a buyback after three years just shows how sure Ather is about its product. People will say Ather is the gold standard in e-scooters and coming from a seven-year-old start-up, that is commendable,” says Aditya Makharia, analyst (institutional) at HDFC Securities.

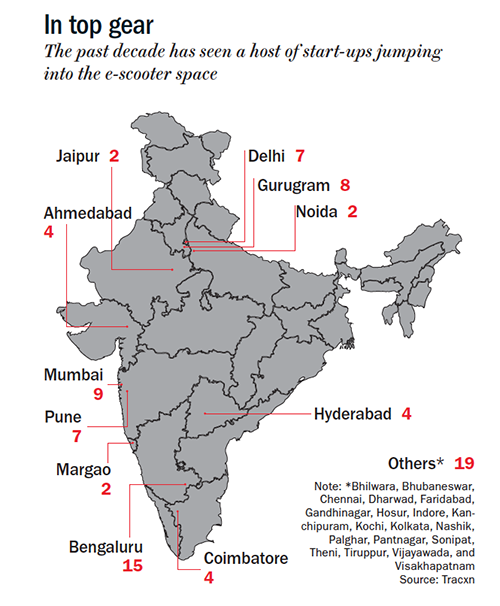

What’s interesting about the mentor-mentee relationship is that it is also an ominous sign of a disruptor handing over the keys of a game-changing electric two-wheeler (e2W) to the country’s largest seller of the conventional internal combustion engine (ICE) two-wheelers. And that’s not good news since the trend of electrification of vehicles has already eclipsed the traditional automakers globally and so it will back home, and to begin with, in the two-wheeler segment (See: In top gear).

What’s interesting about the mentor-mentee relationship is that it is also an ominous sign of a disruptor handing over the keys of a game-changing electric two-wheeler (e2W) to the country’s largest seller of the conventional internal combustion engine (ICE) two-wheelers. And that’s not good news since the trend of electrification of vehicles has already eclipsed the traditional automakers globally and so it will back home, and to begin with, in the two-wheeler segment (See: In top gear).

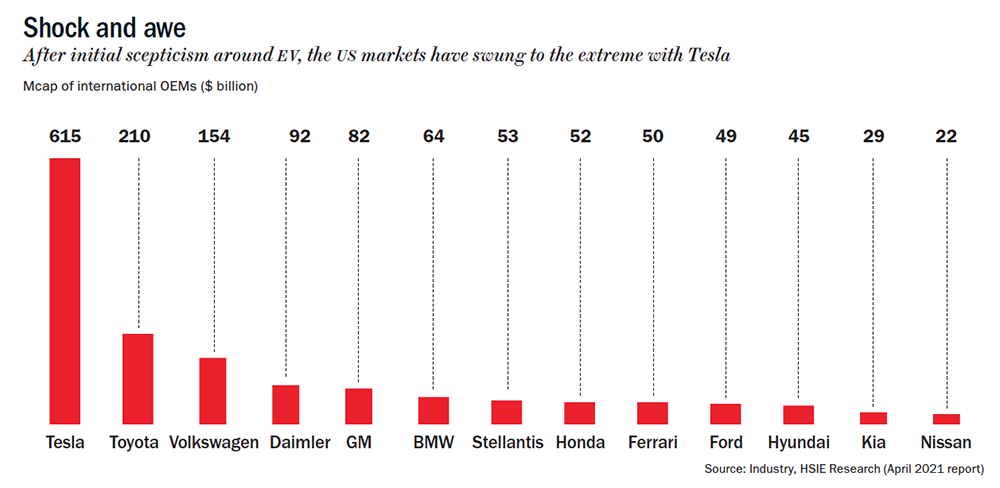

Today, Tesla’s market cap overshadows that of all listed auto OEMs in the US (See: Shock and awe). However, what is not so visible is how e2W maker NIU Technologies, founded in 2014 by the former CTO of Baidu, Li Yan, has raced to $2.3 billion in a short span of time as compared to the $7.3-billion market cap of Harley Davidson founded more than a century ago in 1903. Now, place that number against the big names back home – Hero MotoCorp ($7.83 billion), Bajaj Auto ($16.48 billion) and Eicher Motors, the maker of the iconic Royal Enfield ($9.98 billion). Not bad for a newbie.

NIU’s rise has been impressive. Its revenue rose 18% in CY20 to $375 million and it is already profitable at $32 million. Total volume in CY20 surged to 600,892 (including 28,738 units globally) with Q4 seeing the sharpest jump to 150,000 units. In contrast, Harley Davidson sales fell 20% to 180,248 units, dragging revenue by 24% to $4 billion during the same period. Now, the Nasdaq-listed NIU is looking to up the ante by rolling out its first electric kick scooter in the US and Europe where the demand for e2Ws is rising.

Value investor Chetan Parikh, co-promoter and director of Jasmine India Fund, believes that if the question around disruption is only one of timing, then that’s a very tricky situation to be in. “When disruption is knocking on the door, the stock market won’t take a 10 or 15-year view. It will look at how well-positioned the original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) are to capitalise on the electrification transition and that is where the game lies,” he says.

That is, if the OEMs don’t act quickly, they will be downgraded. In fact, it’s already happening.

While there are no listed EV players in India, the growth of e2W start-ups has been humongous over the past decade. The buzz is too loud to be ignored and analysts are downgrading two-wheeler players such as Hero MotoCorp and TVS Motor. With the impending entry of Ola Electric and others, they see the highest risk to listed incumbents, given their exposure to scooters. Bajaj Auto, with its motorcycles and three-wheelers, is relatively safer with its scant presence in the scooter segment.

All charged up

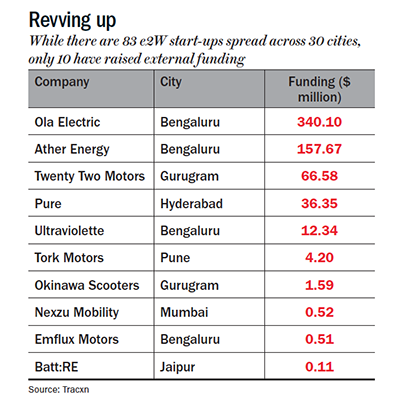

Unlike the passenger car segment where incumbents such as Tata Motors, Mahindra, Hyundai and Kia are looking to play disruptors with their own EV offerings, in the two-wheeler segment, it’s the newbies who are shaking things up. From just a handful of start-ups at the start of 2010, today there are 83 e2W start-ups spread across 30 cities. While only ten start-ups have raised external funding (See: Revving up), the bootstrapped players are already dabbling in prototypes.

What stands out about these start-ups is that they are all building e-scooters. “The first stage of e2W disruption will be scooter because they are urban-centric and are used to travel short distances within cities,” says Binay Singh, analyst at Morgan Stanley. At 23,680 units, e2W sales in FY21 is 1.6% of the annual gasoline two-wheeler sales and 5.3% of the conventional gasoline scooter sales in the country. But what’s pertinent to note is that the actual number of e2Ws sold in India is much higher since the models whose top speed is up to 25 kmph are not registered at the Regional Transport Office.

Singh says, “Our base case assumption is that e2W penetration will hit 10% by 2025 by when the gasoline market starts to decline. In such a scenario, unless ICE OEMs aggressively ramp up electrification, we see risks to the high terminal growth rates priced into domestic OEMs.”

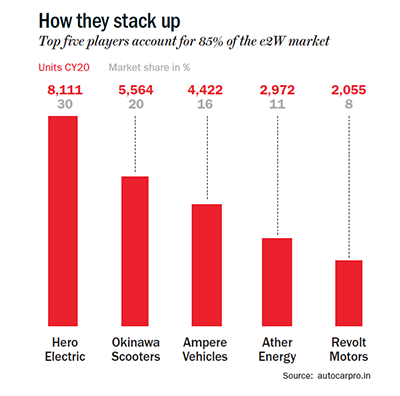

As per data from autocarpro.in, currently, Hero Electric (not part of Hero MotoCorp), which has been in the business since 2000, leads the e2W charge with a market share of 30% having sold 8,111 units in CY20. The automaker currently has 13 lithium-ion scooters in its portfolio. Okinawa is the second-highest seller with 20% market share, while Ampere (16%) and Ather (11%) rank third and fourth, respectively (See: How they stack up). Currently, as per Morgan Stanley research, there are 32 e2W models (10 from Hero Electric) offered by 10 OEMs that are eligible for the central government subsidy which is aimed at supporting the sale of a million e2W between FY19 and FY22. As per the Society of Manufacturers of Electric Vehicles, of the cumulative e2W sales of 52,959 since January 2019, 31,813 units got incentives.

The push factor is also fueling action in the start-up space.

Since CY15 till May 2021, over $8.38 billion has flown into the e2W space of which, Indian e2W companies have seen an inflow of $660 million. In India, as the new subsidy scheme kicked in, CY19 saw $394 million coming into start-ups. “It not only helped them with high upfront capital required in the initial stages of assembly and supply chain setup but also helped improve the quality of the products,” says Jyoti Gulia, co-founder, JMK Research. Among the manufacturers, Ather raised the maximum ($110 million), followed by Vogo and Bounce, in the shared mobility space.

A big factor that spurred investment was also the fact that unlike the previous subsidy, which lasted from FY15 to FY19, the current subsidy is eligible only for high-speed electric scooters with a minimum range of 80 km per charge, minimum top speed of 40 kmph and powered by a 250-plus watt electric motor. The previous incentive helped sales of low-speed EVs that were largely imported and assembled by players.

“FAME-I encouraged EVs to be toys which no customer would want to buy. FAME-II finally changed that completely,” Mehta had said earlier. Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of (Hybrid) & Electric Vehicles (FAME) is a scheme to promote eco-friendly vehicles.

Though the monthly run rate of e2Ws is just 0.5% of overall industry sales, analysts are already raising questions over the ambiguity of the incumbents’ EV plans. Singh of Morgan Stanley feels while the OEMs acknowledge that the future will be driven by EVs, they are not putting money where their mouth is. “While there is no denial, we don’t see firm targets on EV investments, localisation plans and capacities commitment from the incumbent. What an OEM deploys as capex today is what will be sold three years down the line. For now, none have shared a detailed roadmap towards the transition,” says Singh. He does seem impressed by Hero MotoCorp’s investment in the start-up, saying that they need to invest in their own business for EVs.

While the transition by the OEMs is not clear, the business case for EVs is only getting stronger.

Last mile is the strongest

It is not just the commuter segment that start-ups are targeting but also the growing B2B market of last-mile delivery needed by hyperlocal food-delivery firms and also e-commerce giants such as Flipkart and Amazon. According to Akash Gupta, co-founder and CEO, Zypp Electric, which is an all-electric last-mile partner for food-delivery majors and e-grocers, the last-mile fleet size of two-wheelers in the country is around two million, of which 1% would be electric.

However, this number will only shoot up in the coming years.

For instance, Walmart-owned Flipkart is aiming for over 25,000 electric vehicles in its delivery network by 2030, even as it will help set up charging infrastructure around its delivery hubs and offices in India to fast-track EV adoption, especially in Delhi, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Kolkata, Guwahati and Pune. The existing EV fleet of Flipkart includes Hero Electric’s Nyx two-wheeler series with up to 150 km range per charge. Aravind Sanka, co-founder of Rapido, the country’s biggest bike-taxi aggregator, believes that with e-commerce majors Amazon and Flipkart looking to reduce their carbon footprint by 2030 and the growing demand for faster deliveries, there will be faster adoption of e2Ws.

“Currently, the total cost of ownership of an e2W is 20-30% lesser than that of a fuel scooter and it is economical to run an all-EV fleet because the per km expense is very less,” mentions Sanka, whose start-up has raised close to $122 million till date. Concurring, Sandeep Mukherjee, co-founder of BLive, which offers experiential, guided tours with its current fleet of 250 e-bikes, adds, “Maintenance cost is lower compared with ICE vehicles because there are fewer components.”

Though Rapido does not own the fleet, it is encouraging its partners to switch over to EVs. It has on boarded 100+ riders and e2Ws from Zypp, and tied up with Zypp Electric, another last-mile mobility and electric scooter rental services, for its existing 1.5 million rider network. “The cost of switching to complete EV would be high, so, as of now, we are aggressively planning to onboard EV partners on our platform,” explains Sanka.

While a two-million-strong delivery fleet is embracing EVs, so are shared mobility start-ups such as Bounce and Vogo which have been dumping gasoline scooters. “We are selling our fuel scooters to reinvest in an electric fleet,” said a Bounce spokesperson in an earlier news report. It has also placed an order for 3,000 e-scooters with Ampere Electric. The same report quoted Anand Ayyadurai, co-founder and CEO, Vogo: “We already have over 200 electric scooters in our fleet and will be adding significantly more in times to come.”

More importantly, the concerns around charging and range anxiety are also easing on the back of improving technology. Portable fast-charging plugs and batteries are making it easy for consumers to charge e2Ws at homes and offices. Further, with detachable batteries and swapping stations coming up, the ecosystem is slowly forming. For instance, Sun Mobility with IOC will be setting up 100 swapping stations at the latter’s outlets. Charge-up, a battery-swapping provider, has announced that it will set up 3,000 swapping stations by 2024, servicing more than 200,000 EVs, even as other players such as Exicom Power Solutions, and 22Kymco (an alliance between 22 Motors India and Taiwan’s Kymco Global) have joined the race.

Ola Electric plans to create the widest and densest charging network in the world with more than 100,000 charging points across 400 cities. In the first year alone, Ola is setting up over 5,000 charging points across 100 cities, more than double the existing charging infrastructure in the country. “The battery-swapping station network will lead to a drop in the cost of the vehicle, since the battery will either be leased out or its usage will be priced according to consumption,” feels Mukherjee.

Jinesh Gandhi, analyst at MOFS, feels that instead of a pan-India charging or swapping network, a micro market-specific (metros and urban market) strategy will also work. “We will need a good density of charging/swapping stations at every three to four km. Also, charging network per se might not be as important for personal 2Ws as these would be for the commercial segment or PVs as it can be charged overnight at home,” explains Gandhi.

While Ather Energy has an installed capacity of 100,000 units annually at its plant in Hosur, Tamil Nadu, what has got the analyst community excited is the scale and ambition of the Softbank-funded Ola Electric, which is looking at a 10-million-unit facility in Tamil Nadu. To begin with, the company is looking to build a capacity of two million by 2022.

Ola Electric, which spun out of the cab ride venture in 2019, acquired Amsterdam-based Etergo in 2020. The Dutch firm has a fleet of scooters that uses swappable, high-energy batteries with a range of up to 240 km (149 miles). While Ola Electric declined to participate in this story, Bhavish Aggarwal had said in another interview, “When we looked at the opportunity, we realised that the only way to play the game is at scale because you can’t produce EVs at low cost unless you play at scale.”

The reason for scale is that there is still a sufficient price difference between a 125cc gasoline and a similar capacity EV scooter.

At what cost?

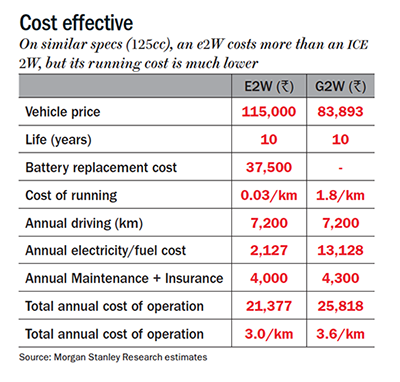

Singh, who made a comparison between one of Ather’s models and Activa 125cc, said that including incentives, buying cost of the e2W is around 40% higher than a similar petrol-fueled 2W. However, the running cost of the e2W is substantially lower than that of the petrol variant given that fuel prices are currently quoted above Rs. 100 a litre (See: Cost-effective)The analyst believes the reason for the cost differential is because the current e2Ws are heavily reliant on imported parts, including batteries. “For price parity, scale needs to come in, because for a global supplier, pricing a million units will make better economic sense than pricing say 5,000 units,” says Singh.

Singh, who made a comparison between one of Ather’s models and Activa 125cc, said that including incentives, buying cost of the e2W is around 40% higher than a similar petrol-fueled 2W. However, the running cost of the e2W is substantially lower than that of the petrol variant given that fuel prices are currently quoted above Rs. 100 a litre (See: Cost-effective)The analyst believes the reason for the cost differential is because the current e2Ws are heavily reliant on imported parts, including batteries. “For price parity, scale needs to come in, because for a global supplier, pricing a million units will make better economic sense than pricing say 5,000 units,” says Singh.

But the good news is that the price of batteries, which constitutes about 40-50% of the total EV cost, is coming down.

According to Gulia, prices saw a massive drop from $1,160/kWh to $156/kWh over the past decade and she sees increasing scale economics push prices further down to $75 over the next 4-5 years. As per JMK estimates, from FY22 onwards, with every 7-8% annual fall in battery prices, the share of e2Ws in the total two-wheeler sales is projected to double. Gupta of Zypp believes that scale will alter the equation for good. “The current cost advantage of 40% on last-mile delivery (with regular 100cc e-scooters) will further widen to 50% once scale drives down cost.”

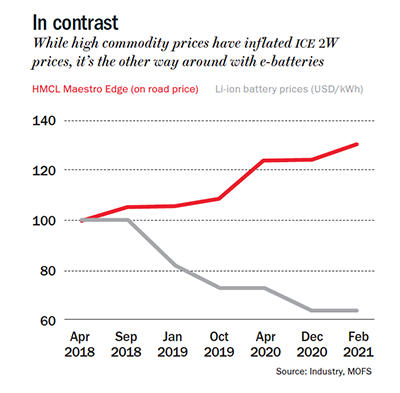

While battery prices have been coming down, the price of ICE two-wheelers have been going up with regulatory change. “While the cost to the customer has risen by around 25% from April 2018 for ICE two-wheelers, the cost of a lithium-ion battery fell sharply by around 24% over the same period,” says Gandhi (See: In contrast). This dive can be attributed to technology improvement and a fall in raw material prices. If battery prices trend down as widely expected, Gandhi adds that e-scooters could attain parity (especially with 125cc scooters) in two to three years on an initial cost of ownership basis. “Due to rising fuel prices, we have seen10x increase in our online sales as opposed to the previous year and 15% increase in the sales overall over the past one year, despite the first quarter getting completely wiped out,” Naveen Munjal, managing director, Hero Electric, had earlier said.

While battery prices have been coming down, the price of ICE two-wheelers have been going up with regulatory change. “While the cost to the customer has risen by around 25% from April 2018 for ICE two-wheelers, the cost of a lithium-ion battery fell sharply by around 24% over the same period,” says Gandhi (See: In contrast). This dive can be attributed to technology improvement and a fall in raw material prices. If battery prices trend down as widely expected, Gandhi adds that e-scooters could attain parity (especially with 125cc scooters) in two to three years on an initial cost of ownership basis. “Due to rising fuel prices, we have seen10x increase in our online sales as opposed to the previous year and 15% increase in the sales overall over the past one year, despite the first quarter getting completely wiped out,” Naveen Munjal, managing director, Hero Electric, had earlier said.

Gandhi does not see ethanol-blending “materially changing dynamics in the 2W segment”. While subsidies are playing a key role in electrification, the industry wants the incentive to run for some more years beyond 2022. “The industry will have a good shot at not being ent on any subsidy once it has about 5% of the existing two-wheeler volume. At present, the 2W OEMs enjoy 25-30% margins. Once we get there, the subsidy can start dropping off,” believes Mehta.

While the government has not made public its intent on whether it will grant an extension beyond 2022, playing the scale game is what will give a fillip to the sector and that’s what the government is aiming for. And so is Ola.

The government on May 12 approved a Rs. 181-billion production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme for manufacturing of advanced chemistry cell battery storage to encourage the creation of 50,000 MW capacity with foreign and domestic manufacturers investing Rs. 450 billion in the sector.

According to reports, Ola is looking at high localisation, including making all the core parts such as batteries and motors, charging stations, infrastructure plans and even a plant to make lithium-ion cells. Explaining his strategy, Aggarwal said in the interview, “We played at scale so that we can price it aggressively, and not just through our manufacturing, but even our suppliers can bring down their costs. The second thing we did was to control key technologies in-house unlike most OEMs in India who are assemblers. We are not assemblers, we are actually designing, engineering and manufacturing key components ourselves.”

Singh believes that a successful launch of an e2W by Ola or any of the start-ups may push listed OEMs into stage three by the end of 2021. That is, the sudden success of an EV model causing a rerating of a start-up, encouraging the OEMs to aggressively announce EV line-ups and long-term EV targets. This, in turn, will accelerate the electrification trend at the industry level.

The race is wide open

Even as the start-ups are gaining ground, analysts believe that the EV market is wide open for both the incumbents and disruptors to make their mark. “Globally, when faced with change, most legacy OEMs have responded at a slow and gradual pace, and this gave the new EV players ample time to get established as EV leaders and gain mindshare among consumers,” points out Singh.

While Aggarwal is looking to price his scooter aggressively and though he has not mentioned the pricing, its likely to be below Rs. 100,000 and above the market leader Hero Electric’s models. In an interview with another publication, Naveen Munjal explained that he would not be comfortable playing the high-stakes game since he believes that a potential commuter will consider an e2W only if it’s within the 10-15% band of the ICE vehicle range.

However, Mehta is clear that Ather will stay in the premium range before going mass. The 450X’s ex-showroom price in Bengaluru is Rs. 1.39 lakh, post a subsidy rebate of Rs. 29,000. “What you could do on a 200cc bike, you can do on a 450X with the convenience of a scooter and more with the most advanced tech,” he says. Mehta’s plan is to focus on one segment, understand it well and provide value. Then, once they have worked out the lowest cost structure, he believes they will have an incredibly good shot at launching a successful mass product.

Citing the example of Tesla, Mehta goes on to add the reason why Tesla was able to build a Model 3 is because it built a Model S.

Playing it safe

To begin with, analysts believe e2Ws will disrupt the OEMs which have scooters as part of their portfolio, and that includes Honda, Hero, and TVS. In the absence of scooters, Bajaj is being seen as the least to get disrupted.

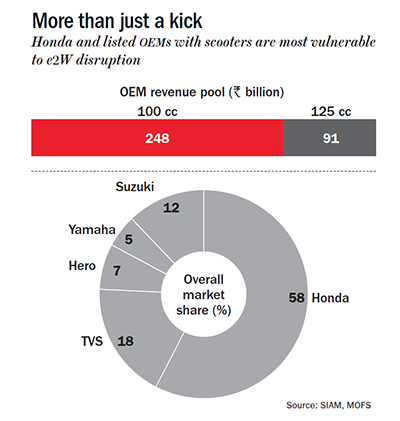

Gandhi of MOFS states e2Ws have the potential to change the competitive landscape of the 5.6-million annual scooter market which generates Rs. 339 billion in revenue and around Rs. 40.7 billion in operating profit (See: More than just a kick). Within that, it is the multinational OEMs such as Honda, Suzuki, and Yamaha which enjoy 70% market share.

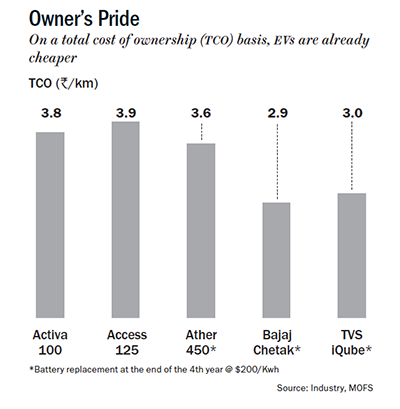

However, Gandhi expects adoption to be faster among 125cc customers owing to the premium positioning, product attributes, and lesser pricing gap. “We do believe that the 100cc scooter would not be immune to electrification for too long. On a TCO (total cost of ownership) basis, our estimates suggest that e-scooters offer 20-25% lower cost of ownership (on a per km basis) as compared to ICE scooters (both 100cc and 125cc),” says Gandhi (See: Owner’s pride). The 125cc category is the bastion of Honda.

YS Guleria, senior VP (marketing and sales) at Honda Motorcycle & Scooter India did not respond to Outlook Business’ email. But in a newspaper report, he had said the company will soon start a feasibility survey for an e2W by getting an existing model from China and that it would take a year or so to complete the feasibility study. Though he did not reveal the name of the model, it could possibly be VGO which the company had recently showcased in Shanghai.

For now, analysts are looking at how the listed players are looking to tackle the EV landscape. Though TVS Motor has launched the iQube and Hero is looking at launching the eMaestro which is being tested at its Jaipur unit, none have given any indication of their investment roadmap for EVs.

Hero and TVS Motor did not respond to emails sent by Outlook Business.

Singh mentions that only if over 50% of their capex is spent on EV can they look at substantial sales coming from EV. In the case of Bajaj, the company has announced Rs. 6.5 billion for a fourth plant to be built in Chakan, Maharashtra for premium range of motorcycles and electric two-wheelers. Rakesh Sharma, executive director, Bajaj Auto, told Outlook Business: “We would want to be on the forefront of EV disruption but we want to calibrate our movement based on how the industry grows and that is not in our hands. We are not concerned about EV market share at this point in time.”

While TVS has sold cumulatively 1,110 units of iQube since June 2020, Bajaj eChetak has sold 1,395 units since July 2020. Ather, which sold 2,972 units in CY20, sold more than 1,000 units in CY21 (up to March) against Bajaj’s 778 and TVS’ 1,076 units (up to April). Singh believes the jury is still out on who will create the EV brand first and manage to hit the magical number of 100,000 units. For now, the e2W players are selling only in 10,000s. “Getting 1% market share is tough and that’s where the fight between incumbents and start-ups will play out,” says Singh, “There will be a time to start being competitive and think of market share. Right now, we need to have the wheel moving. We need to understand technology, we need to understand how the customer will adopt it, we need to train our people, dealers, etc. So, our objective is to build capability.”

Capability is also what Ather is gunning for. “In a couple of years, you will start seeing the scale advantage kicking in. Look at NIU, it went from having zero margin to roughly 25% gross margin in four years. From selling 50,000 units per annum to half a million units, they increased margin by 25%. That’s a story that continues to play out in every evolution,” explains Mehta. Besides incentives and the huge ecosystem around EVs in China and other global markets, one of the reasons behind NIU’s success is also its partnership with 19 scooter-sharing operators across 14 countries. The operators run large fleets which commuters can rent by the minute.

Future tense

While analysts don’t want to stick their necks out on who will emerge victorious in the EV transition, they sure don’t see the market valuing the incumbents like they did in the past. “You have to be very careful as to how you play the incumbent when you have a very disruptive player. The OEMs will continue to make profit but the market will give them lower and lower discounting,” feels Parikh of Jasmine India Fund.

Singh believes the hesitancy of the OEMs is understandable. “When you are selling low volume with high imported components, your margins tend to be low. Hence, companies are slow to respond as they want to balance near-term profitability versus long-term profitability.”

But then it’s a classic chicken-and-egg situation – if the OEMs don’t bite the bullet now, the eventual long-term growth and hence, profitability itself, will be in question. For Hero, scooters contribute 6% to its volume and the company enjoys 7% market share in the domestic scooter segment, while TVS has the highest exposure to scooters, with over 30% of the total volume coming from domestic scooters. While both Makharia and Singh see listed OEMs facing the brunt, Gandhi believes the bigger threat will be for Honda.

For now, analysts are working with guesstimates. Gandhi believes it will take another three to five years for a clear leader to emerge in the e2W landscape. Singh of MS says in CY21, the monthly run rate will hit 7,000 per month for e2Ws versus the February 2021 run rate of around 5,000 per month. “The increase will be driven by the Delhi EV policy encouraging commercial 2Ws to shift to EV, which could drive an incremental 5,000 per month in volume; Ola’s scooter getting launched and the company ramping up, though volume will remain small,” says Singh. In 2022, Singh sees monthly e2W run rate hitting 25,000 per month with Ola ramping up capacity and legacy OEMs launching more models.

In the interim, Singh points out that immediate headwind of high commodity prices and an industry slowdown post COVID-19 will trigger a derating. “By the time things normalise by FY23, you will have EV headwind. At that point the market will have enough things to worry about,” he says.

While the market seems to be more demanding of TVS and Hero, Bajaj is less susceptible to the EV headwind with its revenue and earnings being prominently driven by exports.

Although Hero has announced a partnership with Gogoro to bring its battery-swapping platform to India, it has not provided any details yet. Singh is not impressed: “There are two key things to consider. One, the timing of these launches, which has been slow, giving time to peers to establish their foothold. For now, Hero has not shared any details on capex. Two, the positioning of models is not clear. Will the e2W launch from Hero Gogoro compete with Hero’s own e2W, Ather’s e2W, and/or Hero’s gasoline model?” Though Hero owns a stake in Ather, Mehta rules out selling the business to the OEM.

Analysts, too, do not see any significant value for now in the Ather-Hero alliance. “The market will value what you are doing on your own rather than owning a stake in a start-up which is more a SOTP play,” says Singh.

Even as analysts seek clarity, the OEMs are adopting a wait and watch approach. An unperturbed Sharma says there is no cause for alarm. “Big investments cannot come as the technology is still evolving. But we won’t be caught in the Kodak moment for sure,” says Sharma. For now, Bajaj is selling its e2Ws in Pune and Bengaluru, the turf of Ather, and plans to be in 24 cities within a year. “We had to shut out our bookings for eChetak because there was much more demand than what we could supply,” says Sharma.

Clearly, the race for electric has begun but round one seems to favour the start-ups. As for the OEMs, Samir Arora, founder of Helios Capital, sums it up best: “Disruption doesn’t mean we will go to zero demand but that we won’t buy a cyclical play in a down-trending industry. Why bother so much about one sector when there are others in play?”