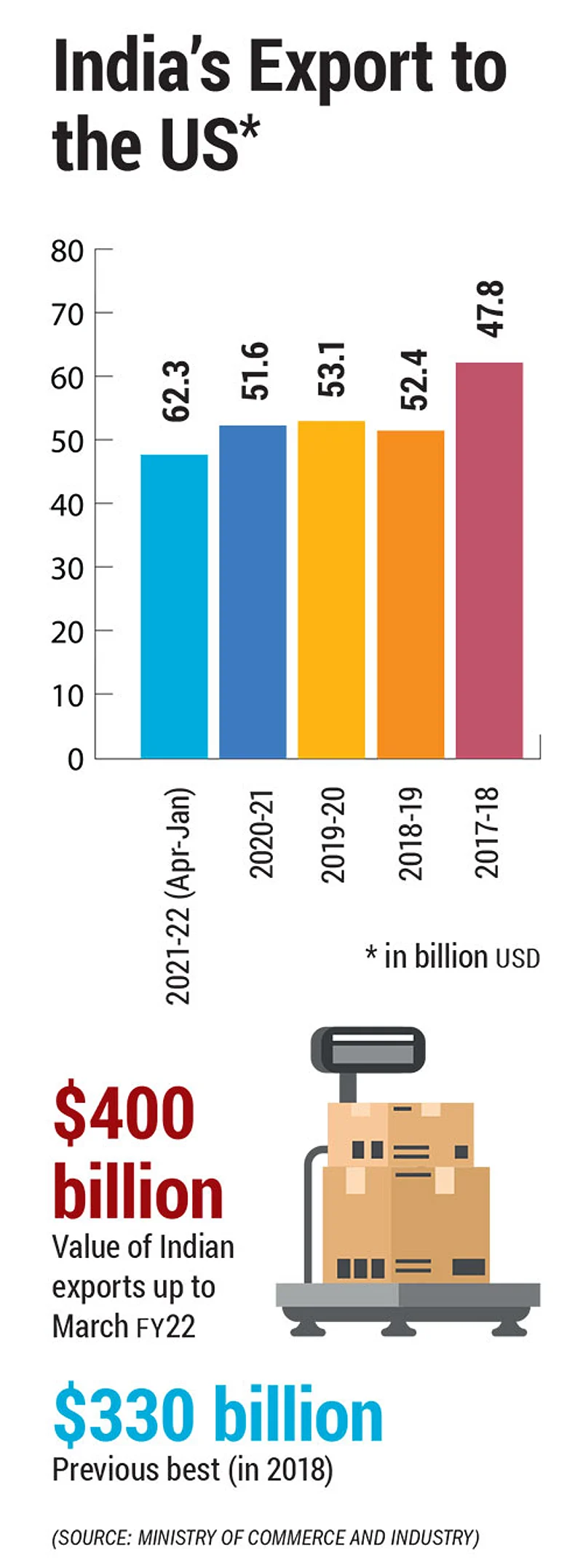

In March, India achieved the target of $400 bn in exports even before the fiscal ended. It had achieved the last fiscal high in 2018, when it recorded exports worth $330 bn. Clearly, India’s export sector, plagued by a decade of lackluster performance, is on a roll and has beaten the pandemic.

Commerce minister Piyush Goyal is also optimistic about achieving $1 trillion worth of merchandise exports by 2030. It means the country will have to grow at a CAGR of 14% between 2022 and 2030, increasing its share in global exports to 5% from 0.55% in 2019.

But, there is a glitch. our largest trading partner, the US, has announced its plan to promote its own version of Make in India. In his State of the Union address, US president Joe Biden possibly did a Donald Trump—who emerged as an epitome of anti-globalisation during his presidency—when he said, “We will buy American to make sure everything from the deck of an aircraft carrier to the steel on highway guardrails are made in America.”

So, in the face of falling income levels, rising debt, high inflation and a raging war between Russia and Ukraine, is there no difference left between a Democrat or a Republican president in the US?

The China Challenge

The rising tension between the US and China over the years had given birth to the strategy of China plus one. Under the policy, multinational firms moved out of China to other countries, like Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam and India. It has been investing heavily in its domestic manufacturing sector by providing production linked incentive schemes to invite domestic and foreign firms to make in India and export to the West.

To boost manufacturing in India, the government announced the PLI schemes covering 14 significant sectors of the economy with a total outlay of Rs 3 lakh crore. Apart from domestic players, India expects global companies—mainly from the US—to set up manufacturing plants here.

But, if the world’s most powerful country decides to move out of the model of global supply chains, what will be the future of India’s export economy in coming years?

President of Ludhiana-based Hand Tools Association S.C. Ralhan is of the view that Biden’s speech is more of rhetoric and will not affect India’s future exports. “Every multinational company is looking to make profits. If they see value in importing products from India or other countries, why will they try to produce it in the US? Indian exports are doing well, and if the government focuses on incentivising its exporters in the coming years, nothing can stop India from growing.”

Apart from the traditional basket of exports that includes gems and jewellery and agricultural items, India has been looking to increase its high value exports in the international markets. Engineering goods exports during the April-January quarter of 2021-22 exceeded their target by 85.3%. On a pro-rata basis, the target for the April-January quarter was $89.4 billion, while actual exports stood at $91.5 billion during this period. The US remained the top export market for engineering goods for the period.

The government data shows that all the top 25 destinations recorded growth during April-January in 2021-22 except Malaysia.

To boost exports, the government has announced measures such as notifying RoDTEP (Remissions of Duties and Taxes on Exported Products) rates and releasing Rs 56,027 cr against pending tax refunds of exporters, among others.

Apart from the $1 trillion target, India neds a clear exports roadmap. Photograph: Shutterstock

Less Imports, More Exports

While the US may not be able to reduce its imports from the world immediately, it is a fact that globalisation is on the retreat. Aradhna Aggarwal, who teaches international trade at the Copenhagen Business School, Denmark said, “World trade has reduced significantly since 2011. For India to survive the next wave of trade protectionism and anti-globalisation sentiment, the government should focus more on increasing exports rather than reducing imports.”

The current Make in India pitch is more inclined to reduce imports, rather than being competitive in exports, according to Aggarwal. “When your focus is entirely on reducing imports from outside, it often leads to cutting down on raw materials that can be used to be competitive in exporting high-end products,” she says.

Over the years, China, for example, has created an ecosystem for its export-oriented growth. It not only has created over a 1,000 special economic zones but has also extended loans to Africa and other countries to create a market for its products. Which is why, despite the US trade protectionism, China has not been impacted.

“India’s SEZ policy has been a failure. Its industrial parks, including textile and mega food parks have been even less successful, resulting in it losing out on its comparative advantage in traditional products to new production centres in Southeast and South Asia, the Middle East and North Africa,” Aggarwal says.

Global Protectionism

Even as the US retreats from being the promoter of global free trade, every country is looking to safeguard its interests by getting into some sort of a regional alliance. The African Continental Free Trade Area became effective from January 2021, while the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)—a free trade agreement among Asia-Pacific economies—came into effect from January 2022.

India, which signed more than a dozen free trade agreements (FTA) in the last two decades, has been wary of joining RCEP because the previous trade agreements led to an increase in trade deficit with other countries. A NITI Aayog report pointed out that exports to FTA countries have not outperformed total exports to the rest of the world. India reported a higher trade deficit with South Korea and Japan post signing of FTAs. In fact, India has a trade deficit with 11 of the 15 RCEP nations.

However, for Anupam Manur, a professor at Takshashila Institution, the reason of trade deficit with RCEP lies in India. He says, “Yes, India has a trade deficit with several trading partners, but that is not because of trade agreements. To benefit from trade agreements, India needs to make its domestic industry competitive, focus on increasing productivity and improve the actual ease of doing business. We also need to prioritise and promote industries that can scale up and employ thousands of employees instead of encouraging firms to stay in the MSME sector.”

India walked out of RCEP in November 2019 under pressure from the domestic dairy industry, which would have been exposed to competition from New Zealand-based products. Apart from that, India’s major concern was an high trade deficit with China.

Ajit Ranade, vice chancellor of the Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics, in a recent article, argued that by not joining RCEP, India has let go of $6 trillion worth of Chinese exports market. A report by the Peterson Institute on International Trade shows that by not joining the RCEP, India could be looking at a GDP loss of Rs 450 billion, compared to a gain of Rs 4,450 billion if it were an RCEP participant. Manur agrees with this line of thought and warns India against falling for protectionism. “India’s reluctance to join RCEP is, firstly, a tacit admission of the lack of productivity of Indian firms and a failure of domestic policy. Secondly, it will hurt India by being cut off from free trade.”

As the US, at least in theory, moves towards protectionism and other regional blocks attempt to maximise their interests, India does not seem to have a clear exports roadmap. The $1 trillion target apart, the government needs to be more descriptive about how it plans to evolve and implement this global passage.