India’s GDP growth rate has been tumbling down since FY17 — 8.26%, 7.04%, 6.12% and 4.18% in FY20, going by World Bank data. It began as a tremor and ended with everyone quaking. From the first half of FY19, people began noticing a slowdown, when the growth rate began falling every quarter – from 7.95% (Q1FY19) to the lowest in 11 years at 4.1% (Q4FY20). Just when we thought it couldn’t get worse, the pandemic lockdown began.

Over the next two quarters, we faced the full impact of the virus lockdown and GDP shrank. The economy stopped growing, even at its earlier slow pace, and began contracting. Today, the consolation is that our speed of decline is slowing. It is a bit like telling the Godzilla-overrun town that the monster is retreating. Of course, there will still be crushing and throwing about of people, but you know, in lesser numbers.

To protect the economy from further rampage, the government has announced schemes to encourage manufacturing and drawn out a large Budget for infrastructure development. The RBI had earlier cut repo rates generously, by 2.1% over six cuts, since February 2019 to make cheap credit available. The pump-priming impressed the IMF enough to revise its 2021(FY22) growth estimates for the country to 11.5%. The billion-dollar question: Will that be achieved?

The Budget has certainly given hope that things will look up. Ajit Ranade, chief economist at Aditya Birla Group, believes it has delivered “substantial stimulus” through its increase in Central Government capex to Rs.5.54 trillion from Rs.4.4 trillion (FY21E), has made a “conscious attempt to give more space to the private sector” and has essentially focused on building soft infrastructure such as health and education. Ajay Shah, economist and former professor at National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, wrote in Business Standard’s February 2 edition that the Budget has shown “a willingness to take on problems which had turned into holy cows” referring to insurance and public-sector banks (PSBs). On February 1, finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced increase in cap on FDI in insurance to 74%, and plans to privatise two PSBs and one insurer. Shah writes, “For the first time, a finance minister has said that PSU banks will be privatised. There is symbolic value in breaking past these barriers in our minds.” Overall, the sentiment towards the FY22 Budget looks positive.

Of course, there have been a few misses. For example, Ranade says perhaps there should have been more direct relief delivered to the urban and rural poor through cash transfers, and more support extended to small businesses by driving up consumption, for example, through coupons issued for people to collect goods from local stores. While Dharmakirti Joshi, chief economist at Crisil terms it a “growth-promoting Budget”, he too believes more could have been done for the urban and rural poor, and small businesses.

Shah isn’t too happy about the increase in import duties, writing in the article cited earlier that raising customs duty “induces an inferior resource allocation, hampers exporting firms, and creates the wrong incentives for the firms”. He also points to glaring absence of financial reform, such as the absence of any way to resolve stressed assets, and the speech pushing solutions from 1970s and 80s such as setting up a bad bank to absorb NPAs and a development finance institute to fund infrastructure projects.

The latest Budget seems like a confident step taken onto a tightrope pulled over a giddying height. To get to the other side, the government has to be attentive to its execution even while keeping eyes trained on the endpoint. A tough balancing act, but one the government has to do for its other growth interventions as well. Let’s look at how effective the other nudges delivered have been.

Rebuilding confidence

Rebuilding confidence

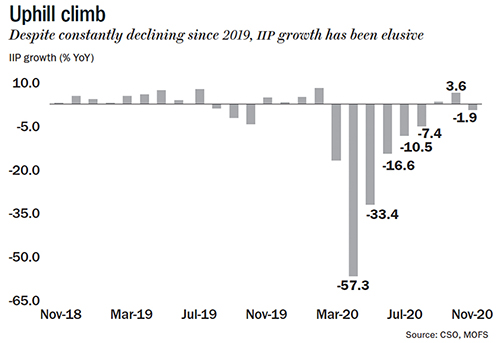

In September 2019, the NDA government completed 100 days of its second term. It was not an easy time. The previous quarter had seen the slowest GDP growth in six years at 5% (See: Uphill climb). Demand had slowed and job losses were on the rise. At the 100-day press conference, there was reiteration of spending Rs.100 trillion on infrastructure over the next five years. Government spending on infra projects had anyway been on the rise since 2011. Shah estimates that, between 2011 and 2020, there has been an increase of 2-3x in infra projects led by the government. A few days later, the finance minister announced a historic corporate tax cut, to 22% from 30%, through an ordinance. For new manufacturing units, it was cut to 15%.Those were two big announcements made within a couple of months.

Sonal Varma, chief economist at Nomura Holdings, welcomes the infra spend as “what the economy needs right now” but isn’t as certain about the corporate tax cut intended to drive up industrial capex. “Corporate tax cuts are a supply-side measure, but if you are an MNC or a domestic firm, you need to see domestic demand pick up and a strong balance sheet before you increase your capex. Corporate tax cuts only help the margins.” The infra push, on the other hand, can have a multiplier effect if land acquisition and coordination between state and central governments, which are usually the cause for delays, are fixed.

Even the infra push needs private players’ participation—22% of the Rs.100 trillion is expected to come from private players with the Centre and States putting in 39% each. But, Varma says the industry’s reticence towards industrial capex may be absent when it comes to infra capex. “Manufacturing capacity utilisation is low so the need for capex there is less whereas, in infrastructure, India faces large supply shortage and there is no problem on the demand side,” she says. Even with private players’ participation, the infra plan will place a huge financial burden on the government. To tide over this, Varma backs the idea of setting up a development finance institution, like a government-appointed committee has suggested.

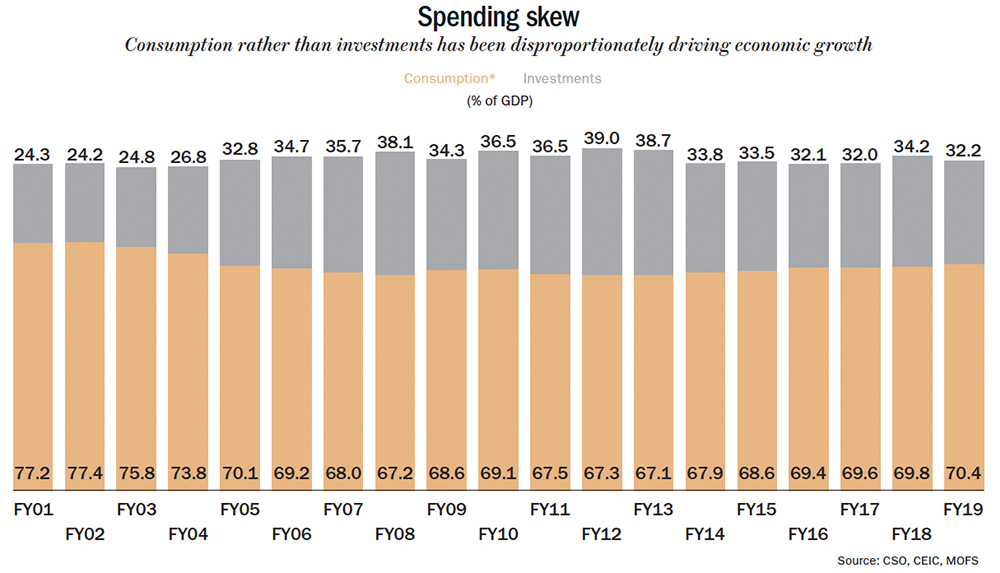

Ranade offers a counterpoint. He says the tax cuts will boost private capex once the pandemic jolt passes but is more skeptical when it comes to private sector participation in infrastructure. On the corporate tax cuts, he says, “They are on par with our East Asian neighbours and they are as competitive as they can get”. On the infra push, he says, “#100 trillion spend over five years means Rs.20 trillion every year, and a large part of it has to come from the private sector. It seems like a huge ask,” he says. His skepticism flows from excess capacity and cautiousness in the economy, and the risk aversion that has come from our experience during the 2008-2009 crisis (See: Spending skew). During that crisis, a lot of infra spending was encouraged and that led to the creation of a lot of NPAs. “So, this time, the dependence on the government to make the infra push work will be higher,” says Ranade.

Shah believes the ideal mix for the infra sector would be the government acting as a developer and then selling it off to a private party. “The private person is a better owner, does better O&M and better cost cutting,” he says. The Budget speech gives reason to believe that the government is headed in this direction. For example, under urban infrastructure, a new Rs.180-billion scheme will be launched to improve public bus service through a PPP model, where private players can finance, acquire, operate and maintain over 20,000 buses. Another example is with major ports, which will be managed by a private player and Rs.20 billion will be set aside to finance seven such projects.

On the corporate tax cut, Shah wants us to look at the larger picture. Private investment in India has been falling since 2011 (See: Once bitten, twice shy). “It has become more and more difficult for a private person running a business in India. Taxation is only part of the problem. The deeper and the more important problems are policy risk and rule of law risk,” he says. Policy risk is when a person fears that governments policies can change arbitrarily. Rule of law risk is when there is arbitrary power in the hands of officials and individuals or firms can be treated differently based on random factors such as winning or losing someone’s favour, which means politicians or bureaucrats can destroy a business even when a business owner has done nothing wrong.

The unpredictability has taken the wind out of private investment but that has not stopped the government from projecting India as a global manufacturing hub.

Manufacturing dream

Varma believes the infrastructure push is vital because without it other major initiatives such as the Production-linked Incentive Scheme (PLIS) simply will not work.

PLIS began with the IT ministry promoting electronics manufacturing in India. On April 1, 2020, it gave the go-ahead, through which the government extended a 4 to 6% incentive to electronics companies, on incremental sales of mobile phones and electronic components manufactured in India. That is, the more they sell locally manufactured units, the higher the incentive. It found takers among the biggies. Within a few months, Apple’s contractors Foxconn, Wistron and Pegatron applied for consideration, so did Samsung.

Perhaps encouraged by the scheme’s reception, in November, it was extended to cover ten other sectors such as automobiles and auto components, advance chemistry cell (ACC) battery, pharma drugs, and telecom and networking products. The highest allocation among the ten was made for the auto industry. In a December 2020 report, BNP Paribas predicted that PLIS would add $520 billion (or about a fifth) to the GDP in five years.

Varma says PLIS is definitely the right move, since India has been presented with a “once-in-a-multi-decade opportunity” with companies trying to reduce its dependence on China. But, she adds, tax incentives alone won’t do the trick. “Ultimately, we will need an entire gamut of ingredients, such as the right infrastructure, regulatory simplicity and labour reforms, to be competitive,” she adds. Crisil’s Joshi too believes that, though PLIS can be effective in the medium term, for longer and sustained growth in the manufacturing sector, there has to be “some heavy lifting” in terms of infrastructure investment and ease-of-doing-business.

Shah, who worked as a consultant with the Ministry of Finance between 2001 and 2005, says he isn’t excited by schemes such as PLIS. “India has one of the lowest wages in the world. You don’t need a subsidy to export from India,” he says. Instead, what a businessman needs is the removal of hurdles placed by the Indian state. In Service of the Republic, his recent book co-authored with Vijay Kelkar, stresses on this. For example, if someone is trying to build a global business by doing sub-assembly in India, then they need a properly constructed Goods and Services Tax (GST) regime in which there are zero tariffs on exports, money moves smoothly, working capital does not get held back by the GST machinery and rule of law reigns. “We need to tackle the root cause and not try to counteract our domestic difficulties with subsidies,” he says.

Ranade raises concerns about how the beneficiaries of the scheme are decided. As of now, the beneficiaries are picked by the government and not by forces of competition, based on a company’s profitability or market share. “For it to work as a long-term measure, winners must be those who can face up to global competition, not those who are handed over their victory as special favours by the government,” he says.

Ranade also agrees with the caution sounded by small manufacturers in India, who fear that they will be left out because of the minimum investment required to avail the scheme and because beneficiaries are chosen based on their topline. He says that the government should work to support these smaller players too, who may be innovative and nimble but may lose to larger companies only because of economies of scale. “The government has to be careful not to eliminate the smaller companies through this scheme,” he says.

To encourage domestic manufacturers, Ranade calls attention to exports. “There is no way we can increase share of manufacturing in GDP from 15-16% to the aspirational 25% without improving our export performance, which has otherwise been abysmal over the last five years. It has been growing at 0%,” he says (See: Optical illusion). For this, he says, we need to pay more attention to exchange rate management.

Our currency, if too strong, can make imports cheaper and hurt the domestic industry and make exports costlier again hurting the domestic industry. “I believe the rupee is too strong right now, when compared to our competitors’ such as Vietnam. We don’t have to make it exceptionally weak, but we have to ensure that it does not become exceptionally strong,” says Ranade. Of course, the RBI can’t simply dial down the rupee’s strength indiscriminately because it would make our imports, of which a large part is crude, expensive and this would drive up inflation.

There was some talk of the Trump administration weakening the dollar to Make America Great Again. Against that, there was fear that the RBI may let the rupee appreciate along with other currencies. Ranade believes there is little chance of the dollar weakening significantly. Even if it does, he is sure that the central bank will not let the rupee appreciate dangerously. To ensure that it does not, the RBI keeps buying up dollars that flow in and has pressed the intervention pedal hard over the past year. That said, exchange rate management isn’t the only area that has seen active intervention.

Self-reliance vs protectionism

A month after the first PLI scheme for electronics was rolled out, in May, the administration unveiled an economic self-reliance drive. There were peculiarities in the unveiling of this campaign. For one, the amount set aside seemed impressive – Rs.20 trillion, or 10% of the country’s FY20 GDP — for another, this massive amount included what was infused through the central bank’s actions, such as cuts in repo and reverse repo rates, and in cash reserve ratio (CRR), moratorium on loans and refinancing options up to Rs.500 billion for SME and housing sector lenders such as NABARD, SIDBI and NHB.

The government spends or the RBI spends. What is the big deal, you may ask? It is more than just semantics. What the government spends comes directly into the economy, therefore the effect is quicker, and what the central bank infuses comes through a third-party such as private or public banks in the form of cheaper credit, therefore the effect can be slow, very slow in reaching the end customer.

There are other fallouts of filling in the blanks with monetary policy measures. For example, when the RBI cuts interest rates, the banks may be willing to lend to medium or bigger enterprises. But, without the broader economy recovering, the banks may hesitate to lend to smaller or micro enterprises, especially with non-performing assets (NPAs) predicted to rise further. In such a situation, the government will have to spend (or use fiscal policy) to stand guarantee for the less credit-worthy smaller establishments. In the current environment, Joshi says, “without fiscal policy, the monetary policy will not reach the last mile”.

Anyway, the self-reliance campaign was unveiled.

Shah says it is not yet clear what this campaign aims to achieve. He says, “Deglobalisation is not in India’s interest, we should be integrating more and more into the world economy.” Ranade, who says the campaign is geared towards making domestic industry competitive globally by offsetting India’s systemic disadvantages, such as higher cost of capital or land acquisition, hopes such protection will be temporary and will be used strategically for select sectors where the switch to Indian suppliers can be made.

“You cannot switch off dependency in some sectors, such as chemicals and compressor for air-conditioners. For example, in API, you need at least ten years to move away from China,” he says. In the long run, he believes, we have to benchmark ourselves against what global players offer in terms of cost and quality. He cautions against a tendency for protectionism.

Varma, who strongly supports the PLIS, too, says that we need to be careful that it does not slip into protectionism. “The primary focus must be on making domestic industry competitive and raising barriers is not a durable strategy. That is, Firm A should not be able to survive only because we have blocked all imports. It should be able to survive because it can compete with global firms in the export market. We should build companies for the global value chain,” she says. If the strategy focuses on barriers alone, say through import levies, then both Varma and Ranade warn that it will end up burdening the consumers.

The Budget, with its hike in import taxes, is a worry on that account. Joshi agrees that this is a protectionist measure but adds that most countries are turning inward. “Overall, it is bad for everybody,” he says.

Harvesting dissent

The pandemic year closed with heated protests along the capital’s borders. Farmers came in tens of thousands from across the country, though a large majority seems to have come from Punjab and Haryana, to protest the passing of the three Farm Acts—Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, and Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act. Though the government claims that the laws deregulate the agriculture sector, the farmers themselves are opposing it as it does away with the MSP safety net, thereby transferring pricing power to private buyers.

Varma says during the COVID-19 lockdown, what really struck her was the extent of India’s food inflation. A lot of countries were placed under lockdown but they did not see their food inflation go up to the extent we did. “This highlights our supply-side bottlenecks,” she says. The bottlenecks can be cleared if investments come in and the Farm Acts could ensure price discovery and bring more investments into the sector, she believes.

Shah was one of the early proponents of the liberalisation embedded in the Farm Acts, but he notes that they only solve a part of the policy problems in Indian agriculture. He has always been skeptical about the traditional machinery of Indian agriculture, in which the usual levers are PDS or fertiliser subsidy or APMC mandi-driven trade. “We need a comprehensive strategy to dismantle the whole thing. For example, there are still the fertiliser subsidies, and barriers to exports and imports to be dealt with. If you keep banning exports of certain produce at random, then there will be no deeper transformation of cropping patterns. The commodity futures markets work badly because of all kinds of government interventions. To do away with all this, you need to carry the different political constituencies along,” he says.

Time to live it up

Besides taking those decisions, the Centre has to find money to spend, in fact, splurge. The Budget has set the fiscal deficit target at 6.8% of GDP for FY22 and the deficit for FY21 is expected to be at 9.5%.

The Centre will have to spend lavishly in the near future, believes Crisil’s Joshi. He says the Fiscal Responsibility Act will have to be kept aside for now and the government will have to spend generously, on health, defense and infra, for sustained recovery. “This will be critical,” says Joshi. For this, the government may need to borrow or use platforms such as the National Investment and Infrastructure Fund (NIIF) to raise more funds and spend on infrastructure. While the Centre stretches itself fiscally, they will have to give the same relaxed fiscal targets to the states since the states account for two-thirds of the spending.

Fiscal prudence is clearly taking a backseat but Ranade says that fiscal deficit is less of a concern now since globally the deficit numbers are “far, far higher”. “We have room to spend extra,” he says, “in the pandemic and the post-pandemic year, the rating agencies won’t be unduly bothered by the fiscal deficit numbers. So, the priority is to spend”, (See: Going all in). If the government is fiscally supportive and COVID-19 lies low, Joshi believes “FY22 will surprise us on the growth front”.

Nomura has been very optimistic about India’s growth prospects. It has given an above-consensus estimate of 12.8% GDP growth for India through 2021. “This is because, number one, there has been faster-than-expected normalisation in India from the COVID situation. Number two, the extent of monetary easing has led to financial conditions improving. There are certain borrowers for whom the credit stress has remained high, but that has more to do with their risk profile. But, for the larger economy, credit stress has come down substantially. And number three, a synchronised global recovery in the second half of 2021 will also benefit India,” says Varma.

According to her, the two most powerful interventions for recovery from the pandemic lockdown was the continuation of the rural employment guarantee scheme, particularly with the reverse migration that happened during the lockdown, and the extension of the loan guarantee programme to MSMEs. “Post COVID, there was higher risk of bankruptcies, so loan guarantees helped with the cash flow mismatches,” she says. Joshi agrees that the scheme helped many MSMEs stay afloat and that the support must be retained for longer since the smaller companies were hit harder by banks’ risk aversion. “If we do not do that, there is a danger to the financial sector,” he says.

The COVID-19 vaccine has infused confidence into the economy. “India is in a sweet spot,” says Joshi, “its infection rate is low, recovery rate is high and vaccine will eventually stop the spread of infection and that will inspire a lot of confidence. The objective is to control the infection rate. If that is done, people will return to work in factories and in the service sector and consumption will pick up."