Shambhu is a 40-year-old street hawker in Delhi’s Safdurjung Enclave. With an annual income of about Rs 1.2 lakh (around $1,500), his earning is less than India’s per capita income of $2,100. Notwithstanding his economic status, his customers pay him using one of the many apps built on the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) platform by scanning a QR code that he displays prominently above the goods kept on his cart. The UPI is an indigenously developed digital payment platform, whose technological breakthrough has opened immense possibilities for India, and the developing world, for formalising financial transactions in a cash-heavy economy. More than 90% of India’s workforce is employed in the informal sector. However, the informal nature of their employment does not stop the poor and not-so-tech-savvy people from using QR codes to make and receive payments for their everyday financial activities.

This phenomenon is a few years old, and largely a result of two breath-takingly controversial, but daring, decisions made by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government. The first was demonetisation that forced Indians to adopt online transactions to avoid long queues outside banks for withdrawing their own money. The second was Union finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s announcement in the budget speech of 2019 that waived off the merchant discount rate (MDR), the fee collected to pay banks and other service providers for running backend operations, on UPI payments. These moves were complemented by increased smartphones sales and significant drop in internet data rates in this period.

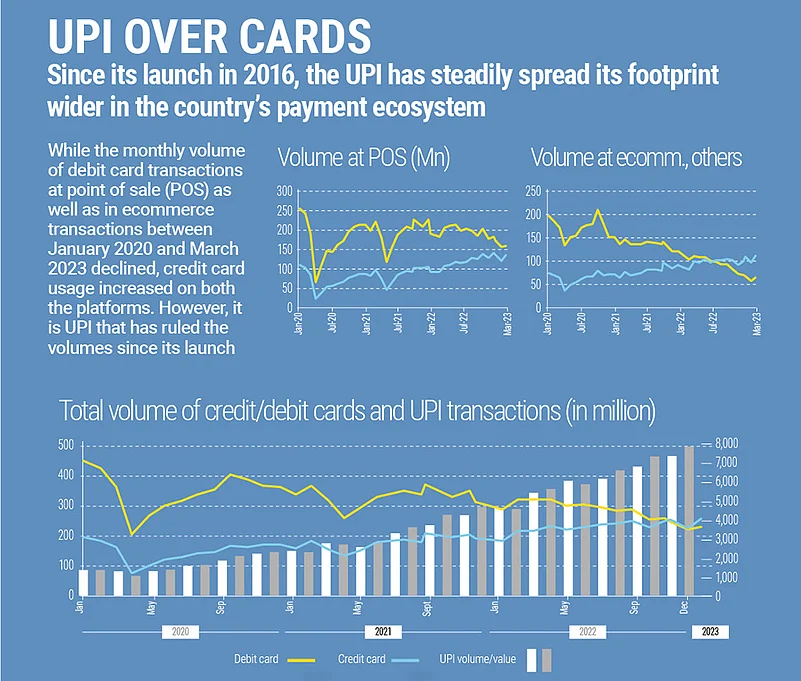

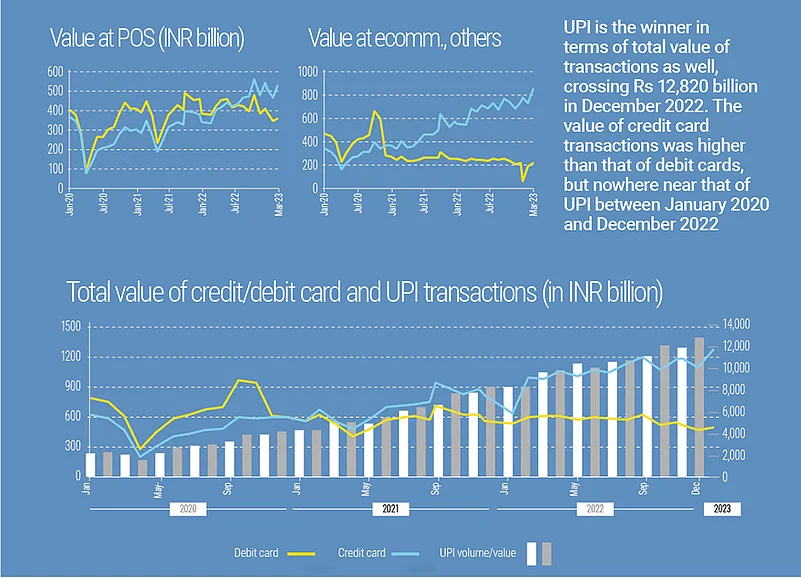

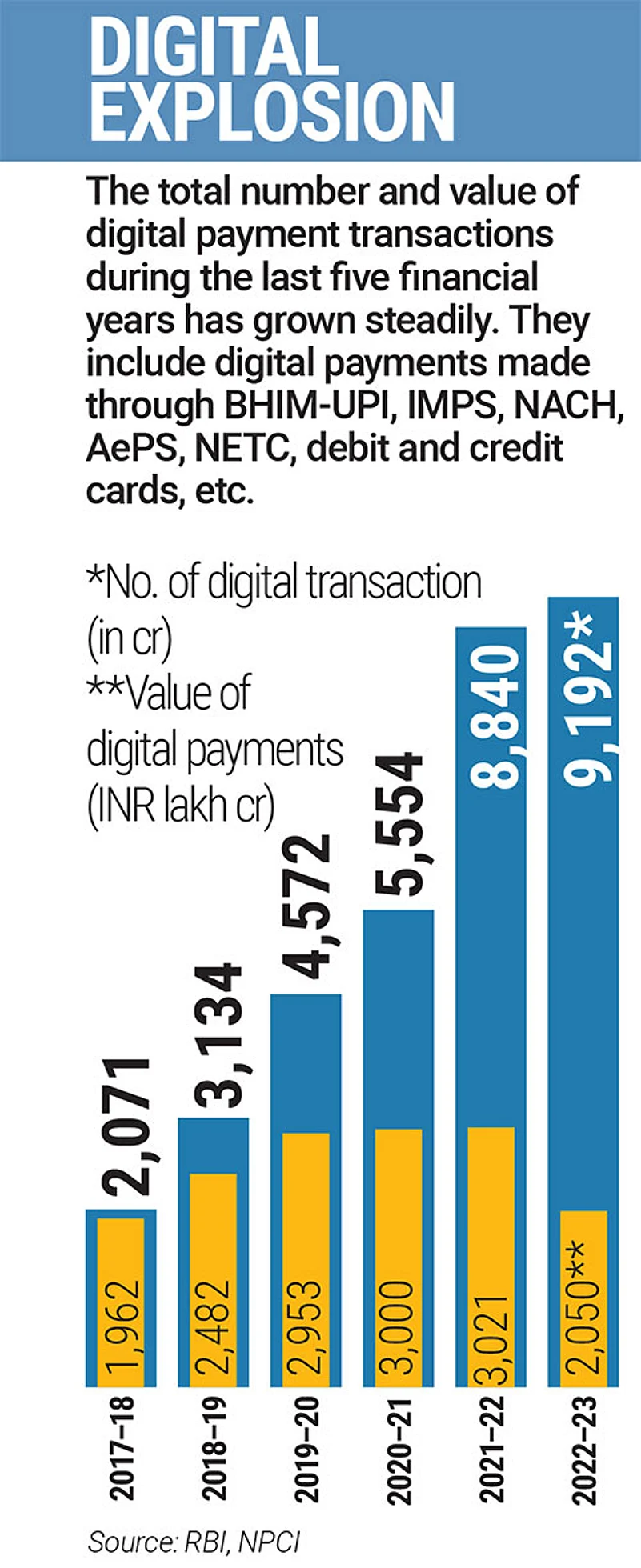

This new reality of the Indian economy opened the gates for mass adoption of a technology that, until then, had remained popular only among smartphone-using Indians for peer-to-peer (P2P) transfers. Since then, UPI transactions have grown at a compound annual growth rate of 81% in volume terms. The corresponding figure for value of transactions is also 81%.

Such has been the rise of the UPI ecosystem in India that the government has allowed the Indian diaspora members to access it using their international phone numbers. The UPI’s supersonic growth threatens the duopoly of Visa and Mastercard, the symbol of American capitalism and world’s most powerful payments companies. They have already lobbied with the US government to be allowed to join the UPI network to offer credit lines to users. In November 2019, Google suggested to the US Federal Reserve to consider learnings from the UPI system while deploying its account-to-account (A2A) service FedNow.

A March 2023 working paper by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), titled Stacking up the Benefits: Lessons from India’s Digital Journey, held forth on India Stack’s merits to foster innovation and competition, expand markets, close gaps in financial inclusion, boost government revenue collection and improve public expenditure efficiency. UPI accounts for 68% of all payment transactions by volume. The use of digital payments, in general, has upped the customer base of smaller merchants, helping to document their cash flows and improve access to finance.

But if neither customers nor merchants pay for using the advanced infrastructure of the payments interface, banks may not feel encouraged to participate in it and third-party service providers may not develop further use cases for it. The government is clearly looking to dominate the global payments ecosystem in the wake of the rising threat of financial sanctions by the United States on countries doing business with Russia and China.

In the UPI system, banks incur cost on every transaction for providing infrastructure for its smooth functioning. A Reserve Bank of India (RBI) discussion paper, Charges in Payment Systems, made public in October 2022, calculated that the payer’s bank incurs a cost of approximately 0.1% in a UPI-enabled transaction, while the beneficiary’s bank incurs a cost of around 0.07%.

Under pressure from banks and fintech companies, the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), in a circular issued in March, allowed transactions made via prepaid instruments, such as wallets, to charge an interchange fee of 1.1% for certain merchant payments above Rs 2,000.

This move can open doors for several fintech companies as well as legacy banks to make profits out of a revolutionary tech that is destroying business models of plastic money companies. However, it also leads to worries that a transaction fee could hurt the very logic behind the success of the UPI system.

Social UPI for the Market

The RBI discussion paper made a case for monetising the UPI, which thus far has been the world’s biggest free rail for payments. It notes: “In any economic activity, including payment systems, there does not seem to be any justification for a free service, unless there is an element of public good and dedication of the infrastructure for the welfare of the nation. But who should bear the cost of setting up and operating such an infrastructure, is a moot point.”

The pricing issue has been bothering the payments industry since the launch of the UPI in 2016, figuring in its talks with the RBI.

Days after the release of the central bank’s discussion paper, the finance ministry tweeted, “UPI is a digital public good with immense convenience for the public & productivity gains for the economy. There is no consideration in Govt to levy any charges for UPI services. The concerns of the service providers for cost recovery have to be met through other means.” It left many wondering what “other means” could mean, even as it suggested that those who make up the payments world and the government differed on the desirability of pricing the UPI.

Soon after announcing its preference for an interchange fee on transactions above Rs 2,000, the NPCI came under pressure to assure everyone that the UPI would remain free for customers and the interchange fee was to be paid by merchants. It also insisted that A2A transfers would stay free.

However, it has opened a Pandora’s box for the ecosystem.

Ashish Das, professor in the department of mathematics at the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay, criticised the NPCI’s decision of introducing interchange charges in a report titled Charges for PPI-Based P2M UPI Transactions: The Deception. He claimed that it would lead to the destruction of the zero MDR regime for small merchants and customers who transact in small values.

Das writes, “As per the NPCI circular, a necessary condition for zero interchange on a prepaid wallet P2M UPI transaction is that the transaction up to Rs 2,000 is done at a small offline merchant.” According to Das, a small merchant is the one who does a daily business of no more than Rs 5,500. Therefore, he argued that all online merchants and large offline merchants who currently accept UPI payments would now be charged an MDR for accepting any payment through the UPI when the payer uses a prepaid wallet.

He adds, “It may be noted that many of the merchants that accept payments through UPI today belong to this category of online merchants and large offline merchants. They would thus get thrust with MDR for all prepaid wallet-based UPI transactions even below Rs 2,000. Even a small vegetable vendor who sells goods worth more than Rs 5,500 per day would have to bear this hit of MDR. This would put a cost burden onto retail merchants, polluting the well accepted digital payment space created by UPI.”

If what Das says comes true, the UPI ecosystem may soon hit the same roadblock that has kept the usage of debit cards at points of sale (PoS) at one of the lowest in the world. The RBI’s Concept Paper on Card Acceptance Infrastructure, published in 2016, noted that the number of card payment transactions per inhabitant in India was 6.7, which was much lower than 249.3 in Australia, 143.4 in France and 16.6 in Mexico. It noted that MDR charges was one of the reasons for a lack of enthusiasm among merchants to accept card payments. Due to the zero MDR regime, the UPI has become more popular than cards, leaving them behind in terms of both volume and value.

The biggest challenge for the NPCI is to ensure that the quest to make the UPI platform profitable does not hinder the government’s larger economic goal of creating an inclusive and burgeoning digital economy. For example, the Centre may not generate any direct tax revenue from merchants like Shambhu, but small sellers like him are part of the chain of last mile consumption of manufactured products in India.

By keeping track of the smallest of transactions in the Indian economy, the government has been able to improve its tax collections over the years. Also, online transactions from the smallest quarters of the economy have led to formalisation of the country’s financial system like never before.

A State Bank of India report published in October 2021 said that the government’s efforts to formalise the Indian economy has resulted in the shrinking of informal economy from about 52% to just 15% to 20%, marking a significant victory for a government that came to power with the promise of eradicating black economy.

Sourabh Tripathi, global head of financial institutions practice at the Boston Consultancy Group, says, “The issue of the UPI pricing is not simple. There is a larger context that we must consider. It is the world’s largest digital payment interface and is of strategic importance to digitisation of the unorganised economy and credit flow to small businesses.”

Annual UPI volumes at the end of March 2023 soared to another lifetime high of 8.7 billion, a year-on-year rise of 60%, with a total transaction value of Rs 14.05 lakh crore, up 46%. Standalone volumes for March stood at 5.4 billion, valued at Rs 9.6 trillion.

“Now all players will, and should, look at their interests and have a view on it. But over time, pricing issues will get resolved as adoption reaches critical milestones. Even at this level of phenomenal size, only 30% of bank account holders use the UPI,” Tripathi adds.

The IMF working paper claims that roughly 4.5 million individuals and companies have benefited from easier access to financial services through the account aggregator framework since its launch in August 2021. This and other aspects of digitalisation of the economy have led to its further formalisation, leading to the addition of around 8.8 million new taxpayers on the goods and services tax net between July 2017 and March 2022 and buoyancy in tax revenues in recent years. Similarly, the India Stack has digitised and simplified know-your-customer (KYC) procedures, thereby lowering costs. Banks that use e-KYC saw a dip in their cost of compliance to 6 cents from $12. The fall in costs made lower-income clients more attractive to service even as it generated profits to develop new products.

Among the key data points in the Economic Survey this year was that more than 1.1 billion bank accounts are being shared under the account aggregator framework. Twenty-three banks are now “live” on it; up to 4.4 million users have either linked to or shared their data on it. This confirms the findings of the account aggregator framework’s performance in August 2022 by Finbox, a B2B fintech credit-infrastructure company, that we are on cusp of the truly exciting. It showed that 90% of those who opted for the account aggregator route closed their loan applications successfully. This is almost twice the conversion rates seen in net banking and manual PDF uploads.

The Finbox survey, which covered over 3.8 lakh accounts holders, also threw up another gem: fraudulent uploads fell to 6.4% from 11.04% due to direct data-transfer between financial information providers and financial information users.

The account aggregator framework is creating a large marketplace, based on customers’ consent for sharing data for all kinds of financial vendors. It does away with the earlier carpet-bombing approach to customer acquisition.

Do recall the following words of Sitharaman’s FY24 Union budget speech: “A national financial information registry (NFIS) will be set up to serve as the central repository of financial and ancillary information. This will facilitate the efficient flow of credit, promote financial inclusion, and foster financial stability.” The NFIS can be a game changer in ways not imagined. It will breathe life into an idea flagged by the High-level Task Force on Public Credit Registry for India (2018), which was led by Y.M. Deosthalee, ex-chairman and managing director of L&T Finance Holdings. In one stroke, the NFIS will do away with the information asymmetry even as it betters visibility on all matters—financial and beyond.

The short point in all this: With the India Stack as it stands, the proposal to let banks offer credit on UPI down the line read along with the AA framework (which is gathering heft) and the in-the-works NFIS, we are looking at force multipliers galore.

Robbing Peter to Pay Paul

Unlike the developed world, emerging economies like India need to find ways to reward the private sector without ignoring social justice. While the Modi government must reform the economy to improve its long-term growth potential, who bears its initial cost is the biggest question.

The debate over the UPI pricing is one of ownership and the returns on investments private players can pocket, without which they will give up on the sector.

In the absence of Indian founders’ zeal towards building a UPI market, foreign players like Google Pay and PhonePe have captured the market, denting the Modi government’s vision to create more indigenous ownership of new age businesses. Seeing Indian companies losing edge on a system that is futuristic forced the Centre to come up with haphazard rules like a 30% cap on market share.

The NPCI in November 2020 had said that payment firms will not be allowed to process more than 30% of the total volume of transactions on UPI from January 1, 2021. The announcement was made to check the duopoly of foreign firms which had already captured the lion’s share in India’s UPI-based payments market. But the NPCI was never sure of the technicalities of its circular being effective without compromising with the efficiency of the system. This is why it has extended the deadline for the implementation of the cap, and Alphabet Inc.’s Google Pay and Walmart-owned PhonePe continue to rule the Indian UPI market with a combined share of about 80%.

“Due to zero MDR, the UPI has become a game of acquiring customers through cashbacks. The top two players are not necessarily the best in their UPI infrastructure. They happen to have deep pockets, with which no Indian company can compete. While the government wants Indian companies to compete globally, its policies do not allow them to compete with global players even in the domestic market,” says a founder of an Indian fintech company that could not enter the UPI segment due to its zero MDR regime.

Despite the government’s pressure to keep UPI as a larger-than-life service with the Indian economy, the RBI has been trying hard to make the system financially viable in the long run. The RBI paper sought feedback on three critical aspects: in the context of zero charges, is subsidising costs a more effective alternative?; if UPI transactions are to be charged, should the MDR be set at a percentage of the transaction value or should it be a fixed amount?; and, if charges are to be introduced, should they be administered by an authorised body, say the RBI, or be market determined?

It needs to be borne in mind that the RBI has not issued instructions about the charges for UPI transactions. Instead, it was the government which mandated a zero charge, effective January 1, 2020.

Now, a distinction is to be made from the Real-Time Gross Settlement and the National Electronic Funds Transfer (NEFT) platforms. These are the properties of the central bank; and public good is privileged over commercials, with costs taken care of by the Centre’s allocation. This is not the case with UPI, the Immediate Payment Service (IMPS) and RuPay, which are owned and run by the NPCI, a not-for-profit entity, with banks as shareholders. Riding on them is the wider universe of pre-paid issuers and card networks Visa and MasterCard.

While there is a subsidy element to the UPI, the Union budget for FY23 cut this to Rs 1,500 crore from Rs 2,137 crore even as the Payments Council of India (PCI) made a pitch for Rs 8,000 crore.

We also need to take on board a technical issue in the UPI which does not get the attention it deserves, that is risk. The UPI enables real-time movement of funds as against the T-plus mechanism for card settlements, but settlement for the participant banks in UPI is done on a deferred net basis. Facilitating this settlement requires the payment system operators and banks to put in place systems and processes to address the settlement risk. This involves additional costs to the system. To this extent, the UPI as a funds transfer system is like the IMPS up to Rs 5 lakh on a real-time basis. Therefore, it could be argued that the charges in UPI need to be similar to those in IMPS for fund transfers.

“The challenge was to get people to get used to the digital modes of transaction. It called for a huge shift in user behaviour from using cash,” says Shyam Srinivasan, managing director and chief executive officer of The Federal Bank. A retail banker before he made it to the corner room at the Aluva-based bank, Srinivasan knows that there are huge gains to be had from the UPI being free. He adds: “Yes, investments are needed by ecosystem participants, but over time, I do see a tiered-pricing mechanism coming in.”

S.C. Garg, former union finance secretary, has an entirely different take. “I believe that all digital payments, including UPI, should be free of charge for customers. While I do appreciate the incumbents in the ecosystem—banks, fintechs, etc.—face costs, only fintechs should be compensated for the costs,” he says. His view is that banks get the benefit of low-cost deposits in the UPI system. “They should be paying fintechs instead. When you cannot be charged for using the cash for payments, there should be no charge for using money in account for digital payments. The UPI is the digital equivalent of cash [transactions] and is only a form factor change,” he argues. In effect, this acknowledges the UPI’s success with the front-end solutions provided by the likes of Google Pay, PhonePe and Paytm.

The UPI, an open-source, real-time and 24x7 fiat currency payment and settlement network, is akin to public goods services like education, physical infrastructure, health and security in its social orientation. It enables interoperability between different banks and payment service providers (PSPs) and, along with the India Stack architecture, is important as a digital public good (DPG). The Bank for International Settlements observed in 2019 that due to its DPG infrastructure (both UPI and Aadhaar), India managed to achieve in seven years the kind of progress in financial inclusion that would have taken 47 years.

“We need not break this chain by bringing monetary frictions with some charges. Further, each country will have unique needs for DPG and a fantastic set of challenges in building it,” says Rohit Bhageria, founding member of Volopay, a Singapore-based fully automated spending and expense management software firm. “But importantly, DPG curtails, or limits, the economic monopolies over data, digital solutions and knowledge platforms, fosters large-scale innovation and creates equitable global partnerships of international cooperation between companies, local ecosystems and government. The recent PayNow-UPI integration is a classic example of large-scale innovation and global partnerships of international cooperation between two countries,” he adds, talking about the interoperability announced by Singapore and India between their respective A2A services.

“The UPI’s initial availability as a free service played a critical role in driving its widespread awareness and adoption. Despite this success, only a small percentage of UPI holders currently accounts for a disproportionately large portion of transactions,” says Uttam Nayak, former senior vice president, Central Europe, Middle East and Africa regions, Visa Direct.

A few banks did charge—ranging between Rs 2 and Rs 5 on person-to-person (P2P) and person-to-merchant (P2M) transactions. On August 30, 2020, the Central Board of Direct Taxes asked banks to stop this practice and refund all charges collected after January 2020. This acted as an inflection point for the UPI, and, in the post-Covid scenario, led to a spurt in transactions. It also kept the economy humming, for had this form of payments not been incentivised, consumption in the economy would have fallen still lower.

But in the here and now, Naveen Surya, founder of FinTech Convergence Council and chairman emeritus of the PCI, asks, “Having had people to get used to the UPI, why not relook at pricing? For instance, you can keep merchant outlets with an annual turnover of up to Rs 20 lakh out of the pricing regime. But on all higher value transactions, of say Rs 2,000 and above, let it be priced. You may add the caveat that this will apply after a certain number of transactions.”

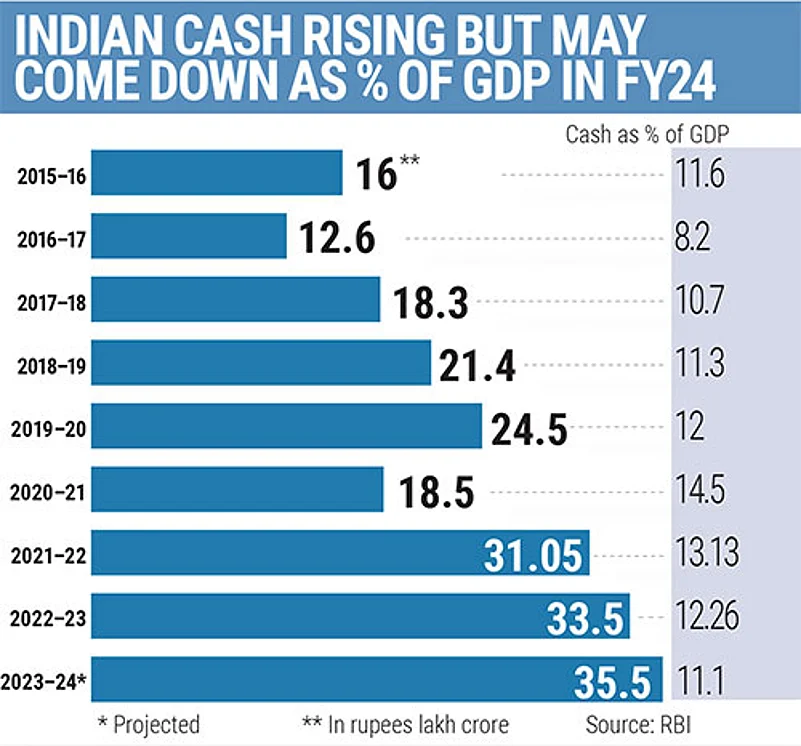

According to Ranadurjay Talukdar, partner and leader, payments consulting, EY India, as things stand, the explosion of UPI usage has led to greater digital penetration in personal consumption expenditure. He says, “Real-time payments [in India] reached $1.5 trillion in 2022—that is half the country’s GDP and more than real-time payments in the rest of the world combined.” However, the cash-to-GDP ratio has also gone up over the years, from 12% to 13.7% in the last decade. “Hence, it is not a simple binary of digital payments displacing cash. That said, the average size of digital payments has come down, showing greater consumer preference for using digital mode for low-value retail payments,” he explains.

While the UPI has fundamentally changed consumer behaviour, the reality is that it involves substantial costs to run the payments ecosystem, which are in part covered by government subsidies. “There is a clear push to unlock monetisation opportunities in the UPI, as evidenced by digital credit lines on UPI, credit cards (RuPay) on UPI and charging for wallet-originated UPI transactions,” says Talukdar. Seconding Surya, he adds, “We are likely to eventually see a tiered-pricing approach to the UPI, with small businesses continuing to receive low-ticket P2P payments for free, and large ticket purchases, payments via credit cards, wallets, overdraft accounts and big businesses generating revenues for issuers, acquirers, schemes and payment service providers.”

Hard Choices Ahead

Looked at differently, the widening of the nature of UPI transactions in recent times appears to suggest that we may be on the cusp of a change. “The emerging model for UPI is a tiered or use case-based approach. This demonstrates recognition of the need to develop commercial models for the UPI, now that it has achieved significant adoption. The offering of credit on prepaid instruments (PPIs) and the MDR on RuPay credit cards is a move in the right direction,” points out Nayak. That is why the move on April 6 by Mint Road to allow banks to offer PPIs via UPI—which will, in effect, mimic credit cards—becomes critical.

Just how will banks structure the offerings and price them? Banks’ PPI-via-UPI comes on the back of another “commercial move” in July last year—NPCI and banks hammered out the pricing on UPI-RuPay-credit cards.

The MDR was pegged at 2%, of which 1.5% would go towards the RuPay card-issuing bank while the rest would be shared between RuPay and the acquiring bank.

The free pricing of the UPI, while being a vehicle of public good, can have a knockdown effect on the digital payment ecosystem. If there is to be nothing by way of the MDR—or a very low MDR—the ecosystem starves. A zero-MDR regime was introduced on RuPay-UPI debit cards in the July 2019 Union budget on transactions of up to Rs 2,000. It could have been given for the smaller merchants with a turnover of up to Rs 20 lakh (that is, out of the GST loop) instead of giving a flat exemption on ticket-sizes of up to Rs 2,000 at all outlets. The larger outlets should have been made to absorb the MDR—they can afford to do so.

Neither the Nandan Nilekani report (2019) nor the Ratan Watal committee (2016) had made a case for zero MDR on UPI transactions but asked for the market forces to decide it. When the government subsidises a UPI transaction, the foregone cost is borne by taxpayers. On the other hand, when users transact through plastic money, Visa and MasterCard networks get to make money as there is a healthy MDR to be carved out. Anticipating the dichotomy, the RBI proposed in the discussion paper—though this suggestion was made in the context of debit cards—that UPI P2M transactions be kept free at merchant outlets with a turnover of up to Rs 40 lakh.

The UPI is at a crossroads. The Payments Vision 2025 document of the RBI calls for increasing the geographical reach of payment services. India has extended the UPI system and RuPay cards abroad. Now, its approach is to broaden merchant acceptance outside of India, starting by catering to Indian travellers. Similarly, the hope is to facilitate remittances by partnering with money transfer operators, PSPs and banks in other countries. But, as the IMF working paper observed, “Seamless interoperability across payment systems, however, requires harmonization of legal and technological frameworks, which is complex and time consuming”.

The issue of the UPI pricing comes amid a public debate over freebies in general. If those who can afford gas cylinders at market rates have no business buying it at a subsidised rate, can the same logic be extended to UPI transactions? This is an aspect which the RBI itself has highlighted: “[T]here does not seem to be any justification for a free service, unless there is an element of public good and dedication of the infrastructure for the welfare of the nation.”

At the same time, stakeholders of the UPI ecosystem know that they cannot kill the goose that lays the golden egg. If regulators tinker with the existing rationale of the UPI through MDR, it could destroy the rapid pace at which India’s digital economy is growing.

The letter that Google wrote to the US Federal Reserve, endorsing the UPI, makes a case for free to very low fee for FedNow transactions. It reads: “Fees to access and use the system must be sufficiently low to encourage market participation by both technology and financial service providers. Also, assuring that transactions below a modest threshold are free of charge would encourage use by lower-income users and improve inclusion of such users in the new digital economy.” If a global behemoth is lobbying with the central bank of a developed economy to keep its A2A service sufficiently free, the dilemma for the Indian central bank becomes rather acute.