On the face of it, IndiGo is sitting pretty. With a handy 40% market share and a route connectivity that its rivals would give their right engine or CEO for (in fact, GoAir just ended up doing the latter), coupled with an incredibly tight-cost structure, IndiGo is in cruise mode. The airline has been around for a little over a decade and managed to come up trumps where most players have succumbed to either strategic mistakes or financial woes.

While the others grapple to sustain market share, IndiGo is making its next move. India’s most profitable carrier is going long-haul, which means it will now be up against much tougher competition, who have not just years of experience but also deep pockets and very solid customer loyalty to back them. From being the big daddy in domestic, it will once again need to settle into the familiar role of the challenger.

It’s not as if IndiGo does not have a presence in international markets. It already has flights to the Middle East and destinations in Southeast Asia such as Singapore and Bangkok. The plan now is to push that to Europe and the US as well.

Owners Rahul Bhatia and Rakesh Gangwal better keep their fingers crossed. For long-haul has decimated the coffers of many an airline in the US and Europe. Closer home, AirAsia tried the long-haul budget airline approach with AirAsia X, which came a cropper. The reasons for failure in long-haul range from overestimating the market size and choosing the wrong routes to the airline’s inability to provide crucial last mile access to its passenger. That apart, airlines such as Emirates and Singapore, who did not have a strong domestic market, successfully became international hubs. Both these airlines, apart from having state ownership, had a presence across the value-chain — owning the airport and airline. Dubai, in particular, had the locational advantage of being a Middle Eastern hub. Though Singapore is not the most conveniently located (Bangkok is), they made it up with high-quality infrastructure and good connectivity. Both the airlines also had the advantage of a clear long-term vision of 10-20 years, thanks again to state support, unlike a host of other private players.

In a scenario, where instances of failure is well in excess of success, IndiGo has its task cut out. It is a far cry from the time it entered the domestic market, when competition was caught unawares. Long-haul will be far from a joy ride since IndiGo faces varying competition depending on the market it wants to be in. For instance, a large long-haul player with a strong local alliance partner could make certain markets almost impenetrable for a new entrant. Clearly, this will be the acid test for IndiGo and making it work will call for big investments, cracking the right routes and not to forget, getting parking slots at key airports. By any yardstick, this itself will be nothing short of a long-haul for IndiGo.

Making it fly

In many ways, the timing could not have been better for IndiGo to enter the Indian skies, when the idea was first conceived in 2004. It had been close to four years since 9/11 and aircraft manufacturers were in a state of turbulence. Business was hard to come by and IndiGo’s two street-smart promoters were quick to spot the opportunity. There was not just a gap in the Indian market for a low-cost carrier (LCC), but a way to squeeze aircraft manufacturers to the bone.

Gangwal had already made a name for himself in the aviation industry over a two-decade stint. After having run United Airlines and US Airways, he was ready for the Indian foray. Until then, he had managed an airline but never owned one. That was his big moment to fulfil that ambition. With Bhatia as his partner, who owned InterGlobe, a travel company in Delhi, IndiGo took birth. In 2006, the airline made its debut flight.

In reality, it was not an easy task to dominate Indian skies. IndiGo set itself for success by drawing a well-crafted strategy that had the ingredients of shrewd negotiation, intensive lobbying and a business model, which was a first for the Indian aviation industry. When IndiGo was at the ideation stage, the competitive scenario had Jet Airways, Kingfisher, Sahara and Air India, all being full-service carriers. All of them were Boeing’s customers and the Seattle-based aircraft manufacturer had a 90% market share in a country where air travel was still limited to a small section of the population. Air Deccan had grown the market with discount fares but was struggling against the biggies. The potential was huge and there was space for more players. The question was how a new, unknown entrant would make the most of it.

By virtue of his earlier stints in airline companies, Gangwal was extremely well-networked with the folks in the aircraft business and knew Airbus would do anything to get a chunk of business from India. In June 2005, IndiGo placed an order for 100 Airbus A320-200 aircraft with the stated intention of launching the airline a year later. The industry was taken aback by the audacity of the new entrant who had not just announced its grand intention but had done so without having regulatory clearance. If Gangwal had checked into Airbus, it was clear Bhatia would fast track the no-objection certificate from the government.

Aware that Airbus would bend over backwards to clinch a deal, Gangwal brought down the price of the aircraft from a little over $60 million to a substantially lower $30 million. For an order of 100 aircraft, it straightway meant a huge saving.

Competition had other pressing needs to address, with the largest player, Jet Airways simultaneously dealing with its own merger with Sahara and also figuring out a way to keep liquor baron, Vijay Mallya’s Kingfisher Airlines at bay. In the midst of all this, the resourceful Bhatia, managed to get parking slots in the prime centres of Delhi and Mumbai, among others, for the to-be-launched airline.

IndiGo’s model was a combination of the best chapters from the most successful LCCs in the world. If it took a leaf out of Southwest in going for a point-to-point network rather than a hub-and-spoke model and simultaneously focusing on a faster turnaround time, it set Ryanair as its role model for better aircraft utilisation. Though the decision to buy the A320 was driven by the steep discount offered by Airbus, that inspiration came from EasyJet and AirAsia. Opting for the A320 ensured substantial savings on maintenance costs and pilot training. To IndiGo’s credit, and more specifically Gangwal’s, there was another compelling reason to deploy a standard fleet. It used 15% less fuel, and given that fuel alone accounts for 35% of the operating cost, it was a smart decision.

In one stroke, relentless execution would ensure the planes spend less time on the tarmac and not subject passengers to a stopover, which increased travel time. For instance, a flight from Mumbai to Lucknow would, in the past, have a stopover in Delhi, while IndiGo was now offering a non-stop connection. KG Vishwanath, former head of commercial strategy at Jet Airways and now partner, Trinity Aviation Consultants, calls IndiGo a case of an uncomplicated, no-nonsense service model, without any frills. “IndiGo merely focused on delivering a clean transportation solution between two points,” Vishwanath says.

No aviation company had ever executed a model of this nature. Raamdeo Agrawal, MD and co-founder of Motilal Oswal Financial Services and a votary of IndiGo, says the airline’s “route-finding power” was a key part of its execution. “Identifying traffic between two centres and then moving around the network in line with that is something they have perfected. On top of this, they designed a product offering, which had the right combination of price and convenience,” he says. This, Agrawal says, gave IndiGo a very unique positioning in the mind of consumers. “It is IndiGo that showed SpiceJet and Go the way to run a LCC successfully.”

In addition, what also worked wonders for IndiGo financially was its sale-and-leaseback model, where a lessor purchases the aircraft from IndiGo and then leases it back to the airline. This asset-light model, explains Vishwanath, brings in cash each time IndiGo takes delivery of an aircraft, knocking off the debt on its balance sheet and giving it the freedom to reinvest elsewhere. Thanks to this arrangement, IndiGo was making an estimated $4 million on each aircraft.

Thus, IndiGo executed its LCC strategy profitably at a time when other airlines were not just grappling with debt and higher fuel costs but competing with the wrong model. A large part of this execution was first done by Bruce Ashby, who joined IndiGo in mid-2005, right after the Airbus deal and then taken forward by Aditya Ghosh, who was handpicked by Bhatia.

IndiGo did not respond to a detailed questionnaire from Outlook Business for this story. Ghosh, too, declined when contacted.

Changing tack

In a development that caught everyone unawares, the 42-year-old Ghosh called it a day at IndiGo at the end of this April. It was under his stewardship that IndiGo got to an enviable position in the domestic market, up against larger players. To throw all this up at the peak of one’s career raised curiosity in industry circles, apart from conjecture on what went wrong.

Ghosh was chosen from the law firm J Sagar Associates, which was the legal counsel for InterGlobe Enterprises. Bhatia brought in Ghosh initially to oversee the legal aspects around the Airbus deal. That was the clincher that eventually got Ghosh the top job.

For Gangwal, Ghosh was always Bhatia’s man. Gangwal had hired Ashby and Ghosh carried the baton onward. Gangwal was peeved by Ghosh’s lack of aviation experience at the time, but he went with the decision as his co-promoter had managed to elevate himself after having successfully lobbied the government of the day.

But Ghosh delivered — IndiGo overtook Jet Airways in July 2012, flying to 30 domestic destinations, with a market share of 27%, with Jet then at 26.6%. At its highest point, IndiGo’s domestic market share was 42.6%.

However, the next step for the airline became a point of serious debate between the two promoters. To Bhatia, IndiGo’s international foray would be no more than five hours of flight time, with the strategy clearly to get more out of the domestic market. That meant flying only to neighbouring destinations such as the Middle East and parts of Asia. The decision to acquire the A320-200 tied in without a hitch with this strategy — the aircraft on full capacity was equipped for exactly five hours of flight time. IndiGo thus started its international flight in September 2011 flying Delhi-Dubai.

Gangwal had a different take, coming from a background where route expansion was seen as the flight to success. When he joined US Airways in 1996, it was largely an east coast airline, and a dominant one, although its international routes were restricted to Paris and Frankfurt. It was his decision to expand to Madrid, Amsterdam, Munich, London and Rome. The new routes did reasonably well until US Airways (and several other airlines) had to bear the brunt of 9/11.

After the change of government in 2014, industry sources suggest that Bhatia’s ability to lobby the government was severely restricted. In mid-2016, the government also scrapped the 5/20 rule, which made it necessary for any airline to have five years of domestic travel experience and a fleet of 20 planes before it can fly overseas. It meant a new entrant such as Vistara, a joint venture between Tata Sons and Singapore Airlines, launched in January 2015, was straightaway eligible to fly to international destinations. For Gangwal, it was an opportunity too big to miss and a story that was up his alley.

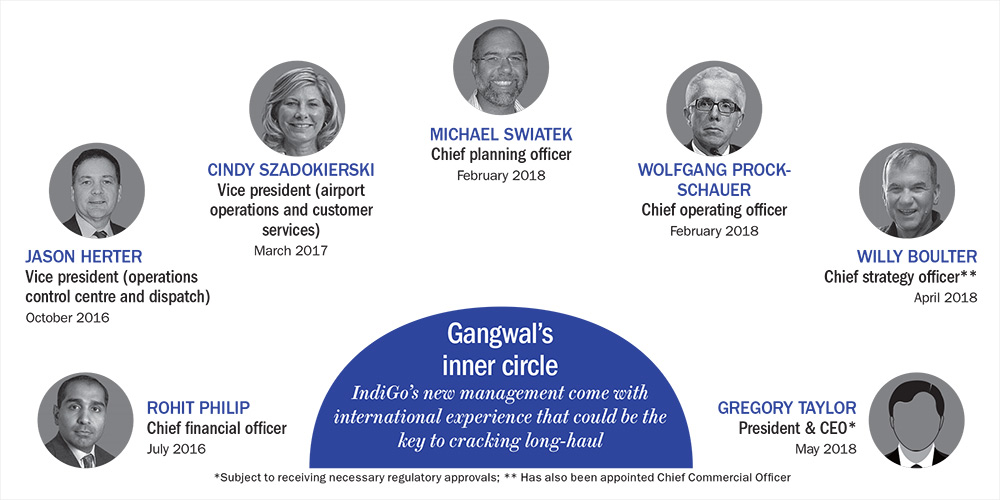

This time, Gangwal managed to have his way. The current team at IndiGo constitutes of people whom Gangwal has known from his United Airlines and US Airways days. They come with international experience, which the airline believes is essential to crack long-haul. Among them is IndiGo’s COO Wolfgang Prock-Schauer, an Austrian, who has worked with GoAir and considered the brain behind Jet’s expansion outside India. Right after Ghosh quit, a statement from the company said the board would consider appointing Gregory Taylor as IndiGo’s next president and CEO. The heads of finance, strategy, planning and operations at IndiGo today are all known to Gangwal. In a more recent development, Sanjay Kumar, the airlines’ chief commercial officer has quit to be replaced by William Boulter, currently the head of strategy.

Getting it right

Setting up the right team may be half the battle conquered in most businesses, but in the airline industry, flying long-haul has been a tricky business for even the most seasoned folks. It is commonly believed that a high passenger load factor (PLF) is one of the key ingredients to success. The thumb rule is that anything upwards of 75% lands the airline in safe territory. That alone is not good enough though.

Michael Boyd, president of the Colorado-based aviation and research forecasting firm, BoydGroup International, cites the example of American Airlines that launched its Chicago-New Delhi non-stop flight in 2005. This was right after India and the US signed the open skies agreement. In its initial years, at its peak, the PLF was as high as 90%, something most airlines would be delighted about, but that soon dropped. “The problem was that the traveller was spoilt for choice. And American was never the first option for him,” he explains. Competitors with a stopover in the Gulf or Europe ended up doing much better, since they were cheaper, convenient and able to attract a larger passenger traffic from the Middle East and India. “American had to sell below cost on this route, which was expected to be a clear winner to begin with,” says Boyd. By the end of 2014, this direct flight service had ceased to exist.

According to him, most airlines make the mistake of overestimating the potential of a route, going with the notion that low fares bring in more passengers. Boyd points out that AirAsia X had dropped its fares by almost half between Kuala Lumpur and Abu Dhabi/London. The sale fare for the Kuala Lumpur-Abu Dhabi route was just $27. The airline was just sticking to its core positioning of being a low-cost carrier, but the strategy didn’t work. “Historically, there was no demand on that particular route and even the cheapest fare was not going to change that,” he says. The service was withdrawn in early February 2010 within months of its launch.

Even for a biggie like Singapore Airlines, its non-stop flights to Los Angeles and New York did not yield results. Boyd says, the A340-500 used was not cost-effective. “The airline priced these flights at a premium because of the non-stop offering. It was alright for consumers only going to or from Singapore but that traffic alone was not enough; they also needed connecting traffic to fill the planes.”

Successful airlines have understood the importance of business travellers and accommodated them smartly. A case in point is Emirates, where, according to Boyd, the price differential between business and economy class can be as high as 8x for a flight from New York to Dubai. “Even then, it is very difficult to wean the business class traveller since there is always high loyalty to an airline,” he says. That loyalty flows from accumulated frequent flyer miles. It is for only the leisure and impulsive traveller, where lower fares could bring in more business, subject to, of course, demand existing on that particular route. Tim Coombs, managing director at the UK-based Aviation Economics, a strategic consultancy for the aviation industry, says LCCs face an inherent disadvantage when flying long-haul. “A full-service carrier manages its revenue because of first class and business class, which ends up cross-subsidising low occupancy in economy. Those like Eurowings have a premium economy class, which is what IndiGo might have to do. Having just economy for long-haul will not work,” he explains.

Overall, there is little to doubt the size of the existing long-haul market. Vishwanath says to get it right here, one needs a strong home market, which IndiGo is already in possession of, or a strong international hub that Emirates and Qatar Airways have built. “It also calls for a strong partner on the other side, which IndiGo needs to get,” he points out. Typically, it takes about six months for any international route to stabilise. A key reason to be in the international business is that it offers a minimum 4-5% higher operating margin than domestic. In India, fuel costs come with 28% tax, while long-haul gives you the option of fuelling abroad on return flights. That alone gives a 6-7% upside on margin. Besides, higher utilisation on international at 15-16 hours per day compares with 12-13 hours, best case, for domestic, which again lends more room to increase margin. “Long-haul, by virtue of flying longer distances and higher utilisation, allows an airline to have a lower unit operating cost,” says Vishwanath.

There have been successes such as Cebu Pacific from the Philippines, which started off as a successful domestic operation. They saw the opportunity in the large number of Filipino workers and offered affordable flights to destinations such as Singapore, China and Korea, before moving to the Middle East. The airline has spoken about wanting to be in the US, which has a huge Filipino population, but has not launched its services yet.

To date, IndiGo’s experience in long-haul is flying five hours non-stop. Flying non-stop long-haul will require bigger and better aircraft, which is why it is said to be looking seriously at the A330neo, according to media reports.

Blue skies, grey skies

So, what will IndiGo need to do to crack long-haul? For starters, what has worked locally may not really matter. Success on long-haul largely revolves around three areas — brand, cost and the route network. Getting parking slots, thereon, will decide how efficient an airline’s route network will be. Mahantesh Sabarad, head (retail research), SBI Cap Securities, thinks one of the key contributors to the airline’s success in the domestic market has been easy availability of landing and departure slots in key cities and quick turnaround of its aircraft. “In long-haul, airlines have to fight for slots and often pay a lot for them, which a LCC cannot afford. Besides, a quick turnaround is not operationally feasible at many international destinations,” he says.

In fact, it will require a sea change in thinking for IndiGo starting from its well-entrenched perception of being a LCC. “This is a difficult business model to replicate in long-haul. Here, passengers are willing to pay a premium, however meagre, for a service and price alone cannot be a determinant of success. IndiGo will have to change the way it is perceived, which is anything but easy,” says Sabarad. All this essentially means IndiGo is constrained in leveraging its learning in the domestic market, or replicating its business model, to make its international operations a success.

So far, IndiGo’s overseas foray, which today connects seven to eight destinations across the Middle East and Asia has been nothing to write home about. The airline has a market share of 5% (among Indian carriers on international routes), with many a false start. It withdrew its flights to Singapore in early 2013, after operating for 18 months. There were two main reasons why it flopped. Firstly, the strategy of reaching out to the end user directly through marketing and advertising and steering clear of the global distribution system to sell and distribute tickets, bombed as the distribution system, on international routes, accounts for 70% of all ticket bookings. The absence of an airline on the screen of the travel agent (this business is globally controlled by three biggies — Galileo, Amadeus and Sabre) means a loss of business. Secondly, in each of its markets, IndiGo faces hyper-competition from other LCCs such as Scoot Air, Tiger and Air Arabia as well as full-service players such as Singapore Airlines which owns Scoot. With Scoot now going aggressive on routes from India to Singapore, IndiGo already faces a headwind.

Agrawal remains optimistic of IndiGo’s chances and insists that it can easily capitalise on its vast network in India, which will act as the perfect feeder, especially from smaller destinations. “If a foreign airline such as Emirates can have a high level of connectivity within India, why can’t IndiGo do the same?” he asks. IndiGo’s understanding of the low-cost model is hard to match (see: Supersonic ascent). “It really does not matter if it is domestic or long-haul as long as you know the basics,” Agrawal insists.

The opportunity that is tilted in IndiGo’s favour is the bilateral agreements that India has with many countries, which remains largely underutilised. According to Joseph Fernandes, general manager (India), Aviareps, a general sales agent headquartered in Munich, this stands at 30% for flights to many destinations in Europe and the rest of Asia. “If those were to be used, it will be advantage IndiGo,” he says.

Considering the network connectivity strength that IndiGo has, Fernandes expects the airline to look at the secondary airports, where parking slots will be a lot more affordable. For instance, if IndiGo does not get a slot at London’s Heathrow, it can still look at other airports in the city such as Gatwick or Stansted. But there are two serious challenges that would then need to be addressed. One, secondary airports in most large cities in Europe are at distant locations, involving a fair amount of travel for the passenger. More critically, these airports do not have good connectivity to onward destinations, such as the US. Given that the top eight to 10 cities in Europe including London, Paris, Rome, Frankfurt and Vienna bring in 30-40% of airline revenue, IndiGo necessarily needs to be at these locations with more than a marginal presence.

Even so, there may be other unexplored opportunities — IndiGo could use India as a hub smartly, for instance. It could bring in traffic from eastern Europe, say Prague to Bangkok with a stopover in India. Europe to Bangkok is a big sector and IndiGo can capitalise on that. Besides, eastern Europe is slowly becoming a big destination for conferences and exhibitions. The other option is to target the passenger flying to smaller European cities such as Cologne or Dusseldorf. Fernandes thinks passengers would be willing to travel an hour by surface transport from there. Here, IndiGo will have to ensure that the overall fare — flight plus train — is much lower than that of a direct flight.

Air pocket

Long-haul will also mean IndiGo will need to go for the wide-bodied aircraft (A330neo). This, apart from the 50 ATR aircraft it has acquired for regional routes, is a departure from what it has done in the past. Sabarad says that a key reason for IndiGo gaining market share in India was the aggressive deployment of aircraft from its “oversized Airbus order book” in easily available slots. “Such an advantage does not exist on the long-haul side of the business. Placing a similar order will now be financially onerous and could lead to serious cash burn,” he thinks.

Fernandes believes IndiGo’s success in long haul will come from a combination of identifying commercially viable routes at both ends, getting it right with the trade, offering good prices and investing in building the brand. “Going long-haul also means adhering to very high levels of efficiency. In Europe, a delay of four hours or a cancellation of a flight means a significant compensation to the passenger,” he says.

It’s probably worth recalling that Jet Airways launched its international service in 2004, but that didn’t go too well. Probably, it spread its wings to long-haul too soon. But then, its inability to achieve a quick turnaround led to poor utilisation and eventually higher costs. Sabarad says, “This meant the airline could not charge a premium for its service and had high code-share dependency, which depressed its margins.”

The consensus is that the long-haul foray, despite notions of higher margins, will only put more pressure on IndiGo’s existing margins. More worrisome, the pressure is mounting on the domestic front too. In a recent report, Citi Research, which has a ‘sell’ on the IndiGo stock, cautioned about headwinds to margins. “The sharp increase in crude prices and the resultant uptick in ATF prices necessitates an increase in fares to offset the negative impact on profit. However, recent trends suggest that pricing power in the Indian aviation sector is low and IndiGo has been unable to pass on the cost pressures to customers in the form of fare hikes,” it states. The report goes on to say that with competitors adding capacity over the next two to three years, there will be an aggressive pricing environment, with operators looking to gain market share. “Given that 70% of IndiGo’s costs are dollar-denominated or linked, a depreciating rupee versus the dollar does not augur well for the company’s profit,” it states. Agrawal agrees that crude oil is playing spoilsport.

For IndiGo, there is still a lot of untapped potential. India’s domestic air traffic was only 117 million passengers in 2017. Competition is not doing anything remarkable that will impact IndiGo’s dominant market position. Harsh Vardhan, chairman, Starair Consulting sounds a word of caution though. He thinks the potential entry of new players with deep pockets and continuous fleet expansion by existing airlines will result in more price wars. “That will make IndiGo also vulnerable. It is a perfect time for a new entrant to create disruption in the Indian aviation market,” he says. In a scenario like this, the long-haul story looks trifle ambitious. And needlessly aggressive too.