Can’t go through life on another’s feet

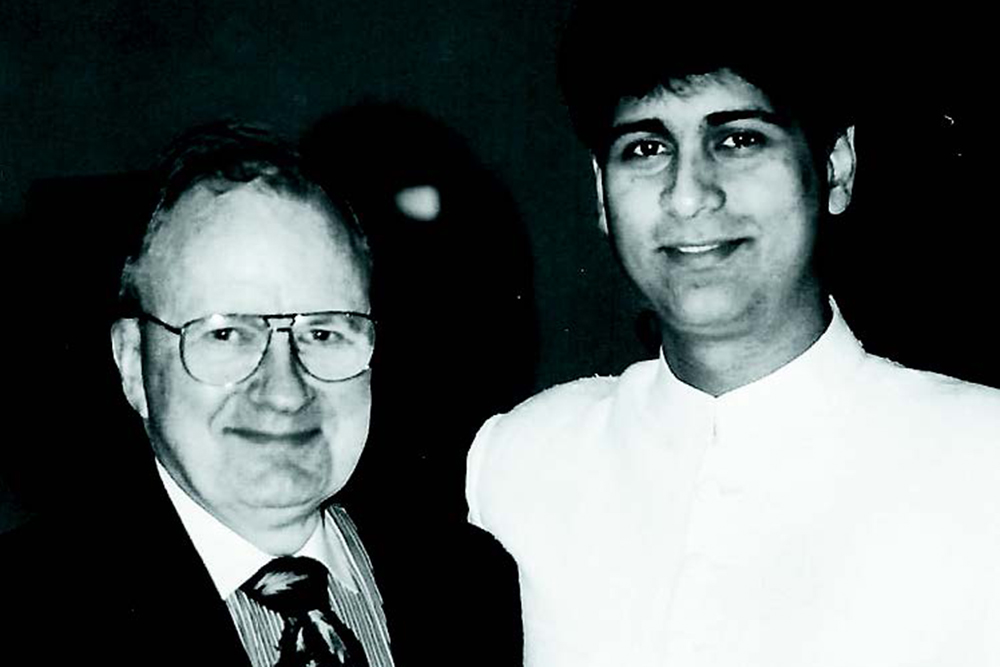

Mom was my first teacher. ‘Listen to your conscience’ is as big a lesson as any. After her, Paul Hoff would become my next mentor.

In 1985, my parents sent me to live with the Hoff family in Denver, Colorado for five weeks. Paul Hoff had been to Harvard Business School with dad and he was a typical rags-to-riches story. He was a bricklayer’s son who joined the US Naval Academy, went on to do his MBA and became a highly successful businessman. He may have had a tough upbringing, he may have been a pilot, he may have been to a cutthroat business school, but he was the most soft-hearted person that I ever knew and the best mentor any child could have had. He adopted me in a way… I used to call him dad and his wife, mom. Unfortunately, he passed away very young in 2001 from a heart attack while walking in New York. It was sudden and shocking.

He played the role that dad could not play at the time, for whatever reason. He would come to India once a year to see me and I would go often to see him. His kids were my friends. He was another life guru, like mom. Just being human and dealing with people in a humane way are what I learnt from him. In spite of all that he had achieved, he was the softest person I had met. To me, the most important quality is being gentle. I am not looking for intelligence, toughness, tenacity or even integrity. The most important quality, to me, is softness. Everything resides in softness. He had his way of saying things like, ‘Go out on a limb because that is where all the fruit is’. That is how he used to push me.

Outside of work, mom and Paul Hoff were like gurus to me.

Outside of work, mom and Paul Hoff were like gurus to me.

At work, I felt like 90% of the people who worked with dad were not really ‘with it’. But there were a few exceptions and one of the most remarkable among them was a gentleman called Mr. Jain. He was the one who coached me in business from the time I joined in 1990 until he was active in 2010. He is the one who helped me understand why we should go global or why we should put everything behind motorcycles. He taught me a simple but important lesson — he asked me, “Do you really think you can go through life standing on someone else’s feet? You have to learn to stand on your own feet.” He said we had no R&D in the company, no technology, no quality and no productivity. We did much better than the others in India but he was taking a global perspective. He took me around the world to shows in Italy, Germany and Japan. I think I must have been to Japan 50 times and he must have come along during at least 10 of those trips.

He also took me to meet our dealers. I remember one dealership in Pune where he took me to their workshop and showed me how an M50, which was to be delivered, was lying outside on the footpath with its engine cover open and rain falling into the crankcase. He said, “See, this is Bajaj. Customers have no choice, so they accept this. But do you really think this will be accepted tomorrow?” He opened my eyes to the reality of our company and it was not just about Bajaj, perhaps it was the case with every other Indian auto engineering company. He said, “You have to stand on your feet. Only you can bring change”.

A funny incident of those times that I can’t forget is what Ajaybhai narrated to me. Ajay Patni is our dealer in Nagpur and a dear friend. I have learnt a lot from him, too, and from a couple of my dealer friends. I asked him if, as a company, we were truly arrogant because dad has always been a fair man, he never overcharged consumers, kept the prices as low as possible and treated his people well. He believed in quality, productivity, hard work and being world-class… he always talked about exports. It’s not his fault that he went and did a goddamn MBA from Harvard, that was the problem! I firmly believe that. I don’t think management is a science learnt in a class but a behaviour you learn while you practice a science like engineering or such. That has been one of our long-standing points of divergence.

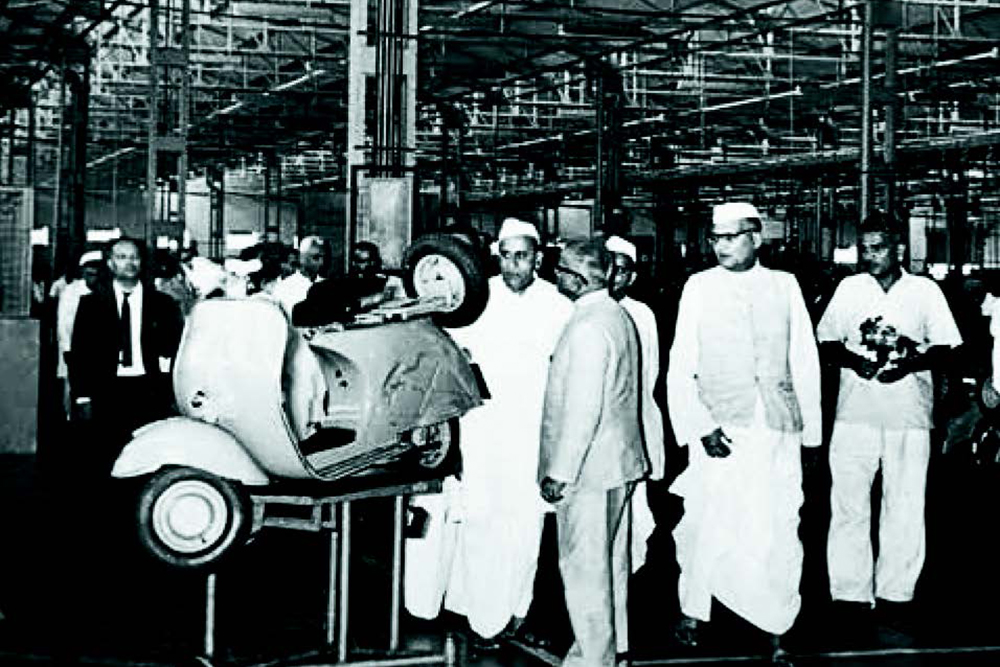

Anyway, coming back to Ajaybhai. I wanted to know — when the man at the top is not arrogant and genuinely wants excellence, can the stories about the company’s smugness really be true? Ajaybhai told me, “Rajivbhai, mein aapko ek kahani bataata hoon.” He said, in his own dealership, a buyer once scrambled in through the door saying, “Arey, woh maine scooter book kiya tha.” The man had booked it 10 years ago in anticipation of his daughter getting married. Given the waiting period, it was common those days that if a daughter was going to get married in 10 years, you booked a scooter for the groom. So had this man who had now received a letter saying that the vehicle was ready. Ajaybhai then asked him what the problem was. The man said there was only one rearview mirror but the catalogue from 10 years ago showed a model with two mirrors. “After 10 years, at least deliver the full scooter,” the man said. So, we used to do anything, even ship it out without a spare wheel, mirror, this and that. Consumers were also keen to get the product and get going.

Anyway, coming back to Ajaybhai. I wanted to know — when the man at the top is not arrogant and genuinely wants excellence, can the stories about the company’s smugness really be true? Ajaybhai told me, “Rajivbhai, mein aapko ek kahani bataata hoon.” He said, in his own dealership, a buyer once scrambled in through the door saying, “Arey, woh maine scooter book kiya tha.” The man had booked it 10 years ago in anticipation of his daughter getting married. Given the waiting period, it was common those days that if a daughter was going to get married in 10 years, you booked a scooter for the groom. So had this man who had now received a letter saying that the vehicle was ready. Ajaybhai then asked him what the problem was. The man said there was only one rearview mirror but the catalogue from 10 years ago showed a model with two mirrors. “After 10 years, at least deliver the full scooter,” the man said. So, we used to do anything, even ship it out without a spare wheel, mirror, this and that. Consumers were also keen to get the product and get going.

Coming back to the story, showing the catalogue to the customer, Ajaybhai said, “Dekho bande, yeh scooter pe toh ladki bhi baithi hai. Are you going to ask me for that also?” That was the arrogance or incompetence or whatever you want to call it of a Bajaj dealer. And this was in 1994 or 1995, after the country had opened up — Hero Honda had happened in 1982 or ‘83 and, if I am not wrong, so had Ind-Suzuki (now TVS Suzuki). Even 10 to 12 years after that, this was the behaviour of the company. That is why Mr. Jain was so important to me. He was one person who was not coloured by the environment he was working in. When I am working in an environment, I am totally conditioned and calibrated by it, but Mr. Jain could think world-class at a time when complacency was the status quo. He tried to speak about this to dad in the meetings but there was a lot of push back from others.

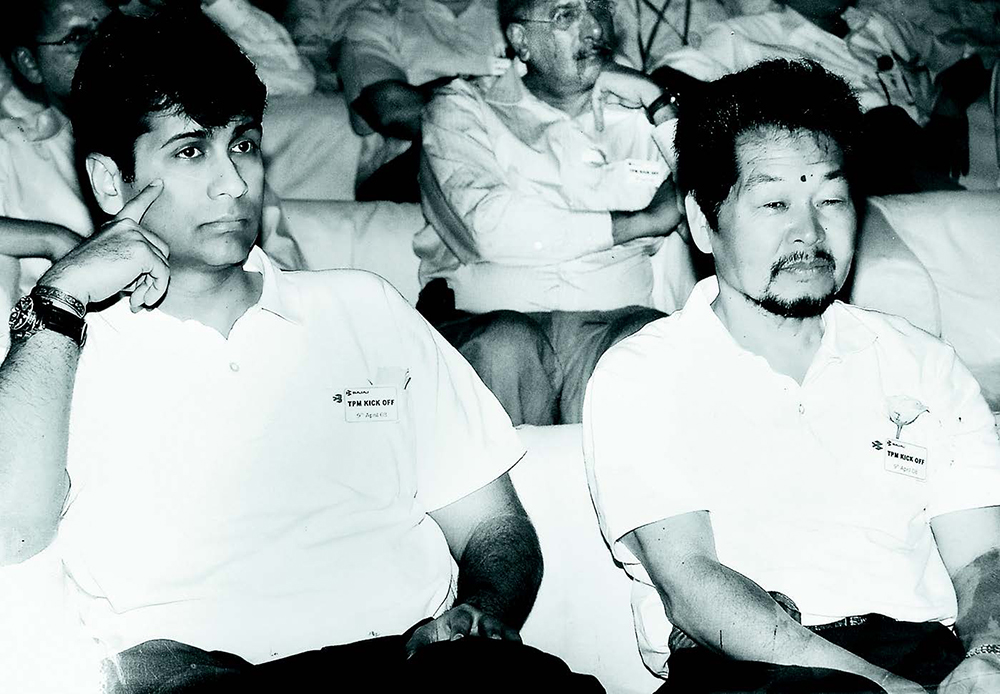

My next great teacher was Yamaguchi San. He had started teaching us in 1996, and every three months, he would threaten to leave because we were useless students. He was with us till 2016. Twenty years he had to teach us; twenty years Mr. Jain had to teach us. We were like the proverbial kutte ki dhum, it took a long time to straighten us out! In his frustration, Yamaguchi San once said, “Business starts when the customer says no.” In December 1990, there was mild panic because the waiting period for customers was down to 18 months. If I had such a luxury, which I never had, I can’t imagine not celebrating in some part of the world. I later understood what Yamaguchi San meant — mindset changes when you have a product on the shelf, whether it is a magazine or a motorcycle, and the customer says no. When nobody wants to buy it, that is when you have to change or that is the end.

My next great teacher was Yamaguchi San. He had started teaching us in 1996, and every three months, he would threaten to leave because we were useless students. He was with us till 2016. Twenty years he had to teach us; twenty years Mr. Jain had to teach us. We were like the proverbial kutte ki dhum, it took a long time to straighten us out! In his frustration, Yamaguchi San once said, “Business starts when the customer says no.” In December 1990, there was mild panic because the waiting period for customers was down to 18 months. If I had such a luxury, which I never had, I can’t imagine not celebrating in some part of the world. I later understood what Yamaguchi San meant — mindset changes when you have a product on the shelf, whether it is a magazine or a motorcycle, and the customer says no. When nobody wants to buy it, that is when you have to change or that is the end.

In 1992-93, after I had worked for two to three years in the company, dad was keen on sending me to the Harvard Business School because it was a family tradition. Dad, uncle, Sanjiv, Manish all went there. I went there for a day to see what it was like and was not enamoured. Dr. John Wallace, a typical, feisty English gentleman whom dad loved and brought in as a consultant, wagged his finger at dad and said, “If this boy goes to Harvard, there will be no company left by the time he is back.”

To him and Mr. Jain, I was their vehicle for implementing change. There was nothing special about me except for the exposure I had got — I had been to the Massey Ferguson plant, to Honda’s UK plant in Swindon, and to all our labs and workshops. I understood manufacturing and quality. What we were doing was completely mediocre and that was a great opportunity for me because, unlike product development or marketing where there is a long gestation period, manufacturing shows you the result in minutes. If I start designing something now, I can see it come out in three years. But in manufacturing, if you do something now, you can see the results in two minutes. If I reduce the cycle time of a machine by 10 seconds, from one minute to 50 seconds, it will produce faster the very next minute. For an engineer, there is nothing more gratifying than seeing something you do in the morning yielding results an hour later.

Picking out the gems

When I started working at the age of 23, my only job was to teach others. That is how I met some of my most competent colleagues who have risen through the ranks to head the most important functions. If I had not worked ground up, I would have never met the real talent that existed in Bajaj Auto. I would have only met the senior people who were 90% good for nothing. The real gems were on the floor, the juniors across all functions. That is when I got about 200 people together in what we called the Streamlined Manufacturing Systems (SMS) group. I used to be part of that across two plants in Pune and Aurangabad at the time.

The group was just made up of engineers who were already working in different departments. I was bringing them together to share knowledge and information, placing them back and then supporting them. Everybody knew that the boss’ son was backing these guys.

The group was just made up of engineers who were already working in different departments. I was bringing them together to share knowledge and information, placing them back and then supporting them. Everybody knew that the boss’ son was backing these guys.

Dr. Wallace stayed on with us, though dad packed off the consulting group that he used to head. Dr. Wallace never said something can be 10% better. He said it can be 300% better. It was inconceivable. If I told a worker to make anything 5% better, they would put the tools down, and here was Dr. Wallace telling us to do 500% better. He had that eye, what we call the Kaizen eye.

One look and he could tell. We used to get so excited and we used to do it.

Earlier, the lines used to produce 128 scooters per shift. When we tried to increase it, there was a strike. Dad was hauled all the way to Bal Thackeray’s house, Matoshree. That is a whole different story… But, when we tried to up the output from 128 units to 150 or 160 and then 210, it was unheard of. No one was doing that kind of production in those days. Assembly lines of similar length in Bajaj today are producing 1,200 vehicles a shift, from 128.

When I joined, all of Bajaj Auto was about 23,000 people, including a lot of temporary and contractual staffers, producing around 923,000 vehicles annually. Today, our Pantnagar plant can produce close to 2 million vehicles with only 1,000 people. What a difference! That was the scope to improve productivity, quality, technology and automation. Mr. Jain told me, “You have to stand on your own feet” and Dr. Wallace told me the same thing in a different way. Once when we were working in the press shop, he had told me, “Don’t defend the past, attack the future.” These words I will never forget. Today, we have made a bold move with the electric Chetak when everybody knows that electric vehicles are not viable. You lose money, there are so many anxieties around them. But this boldness flows from the lessons of the past which I will never forget.

I learnt it the hard way when Bajaj Auto missed two big opportunities in the ’80s. One was the automatic scooter where Kinetic Honda did so well and we lost out on that completely. The second one was the 100cc motorcycle where Hero Honda did very well. I have learnt that in this market, what matters, more than anything else, is the first-mover advantage. All my dealers used to tell me, ‘Yeh Hero Honda ki gaadi toh kabhi nahi bikegi.’ Till today, not in a bad way, I tell my marketing team that the dealers’ opinion counts for nothing. My marketing guru Jack Trout told me that people buy what other people buy. The dealer only talks about herd mentality and he is not going to have the heart to bet on differentiation. So, you have to start something new, you have to create products that create segments, and when you don’t do that and are late to market, you are only seen as a clone. The experience taught me that it is better to try and fail for being wrong than to not try at all because the cost of being wrong is small but the cost of being late is huge. Bajaj Auto, in my estimate, has lost Rs. 300 billion to Rs. 400 billion that it could have made if it had entered those two segments early.

We are not in an industry that is driven by technology. A car today is not that different from a car 20 years ago. It simply looks different. Electric vehicles have been around for 100 years… the first electric car was put together more than a 100 years ago. TVS made an electric Scooty 15 years ago in this country. It is more of an evolution than a revolution. Therefore, it is crucial to be there first.

We are an early starter with the electric scooter. We are not late with that. TVS may have done it 15 years ago which faded away for whatever reason. The problem arises when you have a mature competitor such as Honda and you come out with something 10 years after they have. Nobody is interested then because there is not enough elbow room in technology to make something far superior. The problem with engineers is that they only think in terms of better. An engineer thinks, ‘If somebody gives you 10 km/litre and I give you 11, you will buy my bike’. But it does not happen that way. For 1 km/litre, the herd is not willing to shift. So, knowing the difference between what is better and what is different is intrinsic to marketing.

Between 1990 and 1995, I worked in manufacturing with people like Dr. Wallace and Mr. Jain helping me and with a team of over 200 engineers. We found that we could make whatever we wanted to make but people did not want to buy what we were making. We spent the next five years — 1995 to 2000 — on R&D. Then, I found that we could make, design and develop products, but we couldn’t sell them. That is when I started looking into marketing, starting with exports.

From Yamaguchi San, my most important business learning came when he asked me, ‘What is your job?’ I kept telling him my designation and he kept asking me what my job was. “Do you actually design?” I said, “No”. “Actually make?” No. “Actually sell?” No. “Then”, he said, “you are an overhead… People like you, who sit up in the corporate hierarchy, you fellows don’t do anything with your own hands.” I always tell my people, “If you are Dhoni, you will still slog it out; if you are a great surgeon, you still have to bend over nine hours doing the surgery; if you are a painter, you have no choice but to paint. But we are the only people, the so-called managers, who do nothing but sit in an air-conditioned room, drink coffee, look at a PPT, sign a few papers, and go blah-blah all day long.” Yamaguchi San said, “You think talking is your job but it is not.” He taught me that improvement was my job: “You have to go to work every day telling yourself that you will improve something today. By the end of the day, you should feel you have done that.” That is the kind of culture we are developing or enabling here in Bajaj Auto where everybody who comes to work feels that they have improved on something.

Dr. Rajan, in a certain context, had once told me that the true reward for a man’s toil was not what he gets for it, but what he becomes from it. I ask people these days, “Are you the same person you were when you were doing that, now that you are doing this?” And people understand.

Watch the video here.