When Jyothy’s then deputy managing director, Ullas Kamath, proposed to buy over Henkel India’s operations in 2010, there was stunned silence in the boardroom. Only two years earlier, Dusseldorf-based Henkel had made an offer to buy Jyothy Laboratories. This time, Kamath not only dared to make an offer, but also asked the German board to take a break from India for five years and then acquire a 26% stake in the merged entity.

As audacious as the offer was, things had worsened for Henkel in India. Its operations in the country were deep in red, accumulating losses of Rs.600 crore on a revenue of Rs.400 crore. “We were clear about not wanting to take part in the bidding process. Instead, we gave them a sealed envelope with our offer and left,” shares Kamath, now joint managing director, Jyothy Laboratories.

Having chasing the company since 2008, Kamath hoped to form a working arrangement with it. “Their strength was R&D. We offered to handle the manufacturing and distribution.” The discussions, however, didn’t yield anything. But when A C Muthiah, SPIC’s chairman and Henkel’s joint venture partner, wanted to sell his 16.9% in the Indian operations, Kamath decided to go for the kill.

Eventually, Muthiah sold out to Jyothy in March 2011, and Henkel succumbed two months later, with Jyothy making an open offer for Rs.783 crore. Jyothy was a Rs.600-crore company; Henkel, a €7-billion-global entity. “Henkel was a distressed asset and the seller’s main condition was that the buyer would have to take over its debt; Jyothy knew what it was buying into — a good portfolio,” said the man who had advised Jyothy on the deal, Ramprasad M, the chairman of MAPE Advisory. “It made sense for us,” affirms M P Ramachandran, Jyothy’s chairman & managing director, who started the company in 1983. “We had cash and the best way to grow for us was through inorganic growth. Ujala already had a 70% market share and we knew that developing a brand from scratch would be time-consuming and expensive.”

Clean up time

While there was joy within Jyothy about the acquisition, the turnaround wasn’t going to be easy. Henkel was overstaffed, had limited retail reach and was in the midst of financial turmoil. “The company had not paid a dividend for over 20 years. It was an untouchable,” says Kamath bluntly.

But there was potential in the company’s brands. On a top line of Rs.400 crore across seven brands, Henko was the largest at Rs.140 crore. Others such as Margo, Mr. White and Chek had hit the Rs.100-crore mark at some point, but now only Henko remained in that league. Margo, Kamath says, was the star in the portfolio. “Margo alone was sufficient for us to buy the company. It had a clear neem-based positioning, with a gross margin of 50%.”

To remedy the state of Henkel’s financials, the first thing Kamath did was to focus on its manufacturing. Detergents, which brought in the biggest chunk of the company’s business at Rs.215 crore, had just one plant. Located in Karaikal in Tamil Nadu, this plant would cater to demand from all over India. “This was an illogical way of doing business. How could detergent move from Chennai to Delhi or any part of the north?” points out Kamath. Before selling out to Jyothy, Henkel had also tried to outsource a part of its manufacturing, which ensured there was no quality control whatsoever.

Jyothy, on the other hand, had 28 manufacturing locations for its brands. Kamath wanted to move Henkel’s operations to these plants. Calculations, he says, suggested that a 40% gross margin was possible straightaway if manufacturing could be done in-house. Besides, labour unrest at Karaikal because of the takeover meant a decline in capacity utilisation to an abysmal 6%.

A large part of manufacturing for Henko and Pril liquid was thus moved to Jyothy’s Uttaranchal plant, which enjoyed tax incentives.

Outsourcing was reserved for linear alkyl benzene (LAB), a key raw material used to make detergents. Henkel had earlier signed a deal to source it from Tamilnadu Petroproducts, a company that Muthiah owned, which used to charge more than the market price. Jyothy moved that to an outsourcing model, reducing the dependence on just one supplier.

Bang for the buck

Parallel to manufacturing, cost cutting was necessary to ensure money went into marketing. The competitive landscape and marketing muscle of Hindustan Unilever (HUL) and P&G necessitated this.

Vishwadeep Kuila, founder, Brand Vectors, a marketing consultancy, who handled advertising and communications for Henkel in the 1990s, says modern trade in Europe did not require the company to spend large amounts of money on advertising. “It was all about promotions and that model was adopted in India too. As a result, advertising budgets were always sub-optimal,” he explains. A giant like HUL, on the other hand, was more than happy to outspend a new entrant like Henko.

Kuila adds that, at Henkel, a lot of time and money went into consumer research instead, with the intention to develop a superior set of brands. “It managed to do that but only at the expense of advertising and distribution. Somewhere, the priorities were a little misplaced.”

It is precisely this chink in the armour that Kamath wanted to rectify. Henkel, on an average, had spent just 4% of its sales on advertising and sales promotions. Of this, only 10% was for advertising; the rest 90% went towards offering freebies to the consumer. For instance, the company would give a bucket with every kilo of Henko detergent or launch a ‘buy-one-get-one-free’ for Fa deodorants.

Kuila says Henkel’s India story was a case of shifting strategies. “It started off with an obsession for product quality before the focus shifted to distribution. Once that was not achieved, it decided to enhance the product portfolio.” Time was, however, lost in the process and the company found itself in a tricky situation.

Jyothy, in turn, would spend 7-8% of its sales on advertising and promotions, with the former taking up 75% of the proceeds. Its flagship brand, Ujala, with the iconic ‘chaar boondon wala’ jingle in the late 1990s helped it become the largest player in the whitener business. “The objective was to move as much money as possible to advertising. There was no other way to grow the brands,” says Kamath.

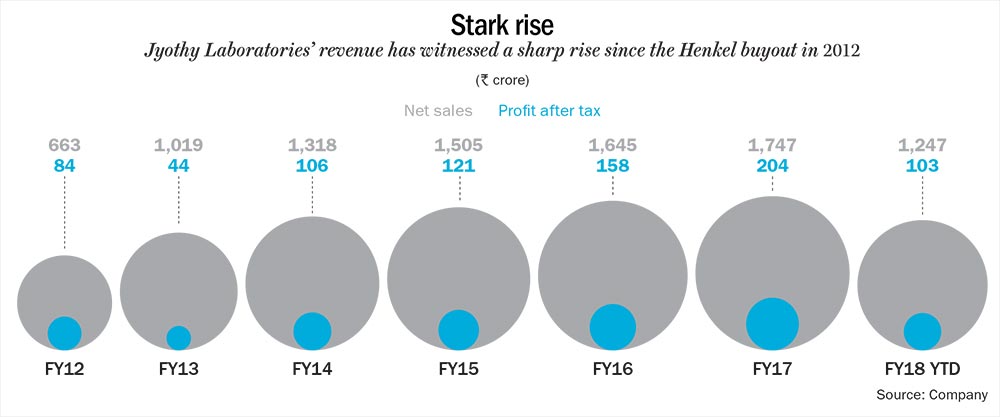

That meant taking some tough decisions, which included raising prices and cutting back on trade margins and promos. All this had a bearing on Jyothy’s financials as well. Apart from taking on a debt of Rs.600 crore to fund the buyout, the company’s sales between FY10 and FY12 were almost stagnant. Net profit of Rs.80 crore in FY10 was down to Rs.44 crore three years later.

Pushing the envelope

Much before Jyothy offered to distribute Henkel’s brands in India in 2008, the German company was close to inking a deal with Tata Oil Mills Company (TOMCO). Once TOMCO was acquired by HUL in 1993, that deal came apart. Some headway was made on distribution once Henkel acquired brands owned by Shaw Wallace in 1999, which came with Margo, Neem and Chek. These were, however, restricted to pockets in east and south India. Even at the time of Jyothy’s acquisition in 2011, Henkel was able to reach out to only 2 lakh outlets supported by 1,500 distributors. In contrast, Jyothy’s brands were sold in 3 million outlets and had over 3,000 distributors.

Even the composition of this reach could not have been more different. For Henkel, 60% of its business came from urban India. Jyothy’s bread and butter was rural markets, which brought in 80% of its sales. Its access to modern trade, as a consequence of the rural tilt, was limited. “We had to use Henkel’s distribution for our brands and take its brands to our strongholds,” says Kamath.

For instance, Henko had 20 SKUs (stock-keeping units). That doubled when it entered rural India. A Rs.10-pack was launched to get in a larger base of users. Jyothy had its own brand, Exo, which was strong in the dish wash bar segment. So Pril, a liquid version that Henkel owned globally, was launched in a pouch. Jyothy was thus able to leverage a larger brand portfolio in its rural markets. “Since our distribution was already very strong, we could get retailers to stock more of our brands. The whole idea was to attack them with a larger portfolio,” he explains.

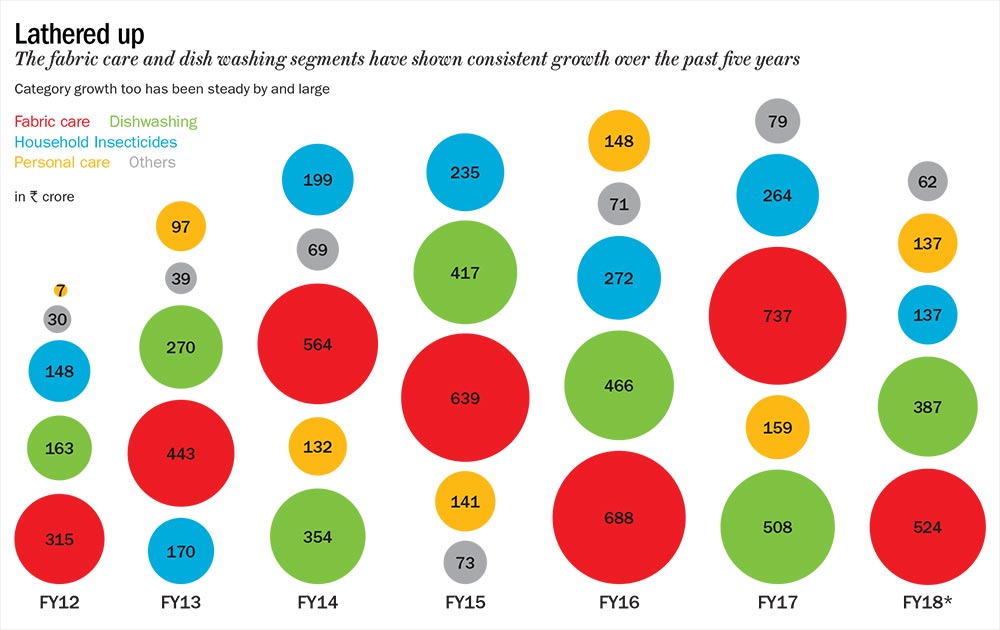

In urban India, where Henkel’s equity was strong, Kamath decided to push Jyothy’s brands harder, especially in modern trade. The strength of a bar and now a liquid gave Jyothy greater ability to negotiate. Pril is placed second in the dish wash category today (after Vim). Between FY12 and FY17, Jyothy’s dish washing business grew from Rs.163 crore to Rs.508 crore in FY17 (see: Lathered up).

The decision to increase prices and rework trade margins was the toughest call before Kamath. He cites the case of Henko, whose positioning was changed from a mid-premium brand to a premium one, against brands such as Surf and Ariel. “For Henko, we changed the packaging to make it look more appealing. More perfume was added to make it a viable competitor to the existing players.”

On an average, each Henkel brand underwent a price hike of 20%. Simultaneously, freebies were withdrawn and Jyothy managed to increase the margin on Henkel brands by 1%. Meanwhile, since its brands were in a strong position, it dropped margins by 2%, but assured traders of more business overall. “It was difficult to convince the traders initially. But when they saw what was spent on advertising, they began pushing both the brands.”

Besides, Jyothy also evaluated each brand and repositioned some.While Ujala’s positioning as an instant dirt dissolver had worked, they realised Henko Matic’s historical positioning on the stain remover platform would not. “There was no way we could take on the larger players, who also spoke of stain removal,” says Ramachandran’s daughter, MR Jyothy, a director in the company. Thus, the brand was repositioned as a cloth comforter and relaunched as Henko Matic Lintelligent. The Henkel detergent portfolio is today worth Rs.200 crore.

Way ahead

The buyout of Henkel has only strengthened Jyothy’s business. Fabric care, for instance, has grown from Rs.315 crore in FY12 to Rs.737 crore in FY17, even though it was driven largely by Ujala, which enjoys a healthy 71% market share. Abneesh Roy, senior vice-president, Edelweiss Securities, says it will always be difficult for Henko to take on HUL and P&G in detergents. “Usually, acquisitions in FMCG are targeted at a few brands, which can drive the business. In the case of Henkel, it opened up distribution in new markets for Jyothy and gave it Pril, a business where penetration levels are low.”

Roy adds that Jyothy will not be able to match the advertising spend of its larger rivals in detergents either. It is a view that Kamath echoes. Chek, a mass detergent, and Mr White, a mid-premium brand, both with low margins restricted to the east and south, will not see any significant investments in the time to come.

“You can make money in mass detergents if you have a strong regional presence with a sound proposition,” says Jyothy. This is evident in the case of Ujala, that is sold only in the state of Kerala now, but clocks a Rs.100-crore turnover. If the low and mid-market brands bring in a margin of 25%, the top end is well in excess of 40%. “Our focus hereon will only be in the top end of the market, which brings in higher margins,” points out Jyothy.

In the case of Fa, which like Pril is a licensed brand, competition is intense, with Vini Cosmetics’ Fogg being the dominant player. Fa clocks a turnover of Rs.20 crore. “We do not see merit in spending big money here for the moment. Besides, there is no unique positioning for Fa,” Kamath admits.

The task on hand is to push fabric care, dish washing and to some extent, household insecticides, where Maxo is up against Good Knight, All Out and Mortein. The biggest opportunity, says Kamath, lies in personal care, with Margo and Neem. Together, these brands clock Rs.200 crore of revenue, with Rs.175 crore coming from Margo alone. He believes there is a clear opportunity in the ayurveda business, where both the brands are already positioned “on the high tide” of the growth story.

To get a slice of that, the company has already launched Margo Face Wash. “We will spend a lot of money on pushing Margo starting next summer,” he says. This is in line with market dynamics moving towards ayurveda, with multinationals such as HUL and Colgate too making their moves. Roy thinks getting into face wash will surely increase the premium quotient for Margo. “There is no doubt that Margo has historical equity but that alone will not be enough to give you growth. It will depend heavily on how much money is spent in this business as it is still under penetrated.”

As for Neem, the thrust will be on pharmacy stores and modern trade. “This segment already has Babool, Meswak and Vedshakti. Neem has equity, but they have to be more innovative,” says Prateek Srivastava, co-founder, ChapterFive Brand Solutions. According to him, the challenge for legacy brands such as Margo and Neem is the perception of being too medicinal. “Today, the game is not just about herbal but bringing in the cosmetic benefit as well.”

Another segment Jyothy is looking at keenly is hair care. Research is underway and Ramachandran sees a big opportunity. “Everyone is speaking of hair fall and damaged hair. There is definitely a lot more that can be done,” he insists. Though he is tight-lipped, he says his products will be out in the market in about three-four years. “We have never entered the market with a me-too product. It will be unique this time as well,” he says.

While Jyothy rides on the success of its acquisition, Henkel’s decision against acquiring 26% stake in the company has come as a setback. Jyothy could have used Henkel’s technical expertise. Kamath, however, downplays it, saying, “It would have been too expensive for Henkel.” After all, Jyothy’s revenues and market capitalisation have taken off impressively since the Henkel buyout.