"I travel 25 days a month. I don’t think my wife really minds,” says Ramesh Tainwala, sipping coffee at his spartan office in the Nashik district of Maharashtra. It’s the 54-year-old Tainwala’s second day at work after formally taking over as the global CEO of Samsonite International, the world’s biggest luggage maker. Based out of Hong Kong, the jet-setting Tainwala’s personal graph tells the amazing story of how a local vendor ended up heading the very MNC that was once his client. Tainwala, a postgraduate from BITS Pilani, began his career in 1981 with a plastic trading company. Five years later, he quit his job to start his own manufacturing unit that supplied plastic sheets to VIP Industries, which moulded them into suitcases. The turning point came in 1998, when Samsonite, after failing to woo VIP into a joint venture, entered into a partnership with Tainwala for his company to manufacture luggage for it in India. Two years later, after failing to making any big inroads into the domestic market, the US luggage major was all set to call it quits. That’s when Tainwala made a bold move.

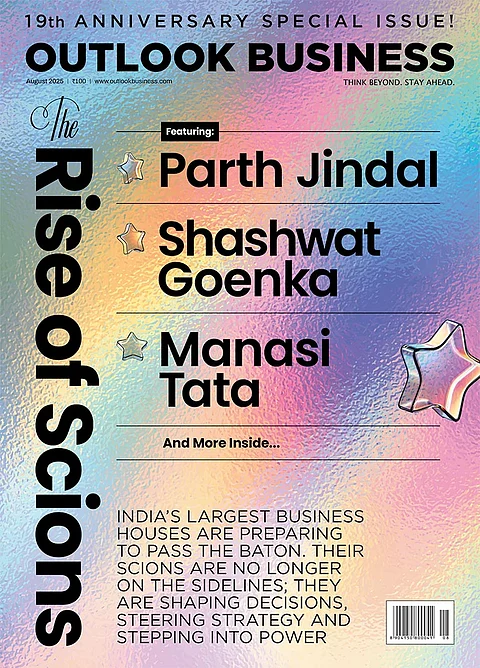

Close fight

Samsonite is giving rival VIP a run for its money

Convinced that there was enough potential in the market, which was then ruled by VIP with over a 90% share, Tainwala got Samsonite to convert the agreement into a joint venture by giving him management control for two years and a 40% stake in the Indian operations. Samsonite took his word for it and has since been amply rewarded.

Convinced that there was enough potential in the market, which was then ruled by VIP with over a 90% share, Tainwala got Samsonite to convert the agreement into a joint venture by giving him management control for two years and a 40% stake in the Indian operations. Samsonite took his word for it and has since been amply rewarded.

Today, India is the luggage maker’s fastest growing market after China and South Korea, fetching 6% of global revenue of $2 billion, while the Nashik unit, housed over 18 acres, is only the third manufacturing base outside of the US.

As for VIP, the once undisputed king has now to contend with a competitor breathing down its neck. The turnaround in India’s fortunes gave Tainwala a stature in the company’s global pecking order. One elevation followed another before he took charge as the top boss. “My mandate is to double our global business every five years. India’s numbers will double every three years,” quips Tainwala, even as an employee walks in with a box of sweets after the traditional Dussehra puja. This steely determination is also an outcome of how it all began for Samsonite in India.

Turning point

Tainwala is very fond of the phrase turning point and to his mind, there are just two in the history of Samsonite in India. The company, which is called Samsonite South Asia here, was up against it from the time it started manufacturing in 1998, when its most formidable competitor, VIP Industries, was not giving away even an inch. “There was very little we could do at the time and things were looking very grim,” says Tainwala.

That is an understatement given that the company’s turnover was barely Rs 10 crore, with all of it coming from the Samsonite brand. “Our cash flows were stressed and our global parent had to fund our salaries,” he recalls. At that point, the factory had retrenched almost its entire workforce (200 of them) and was in the process of winding down its Indian operations. After making a foray into India and China in 1998, Samsonite was finally ready to bid goodbye to both markets. If there were no buyers for the Samsonite brand in India, the joint venture with the CP Group in China wasn’t heading anywhere either. The silver lining, though, was that Samsonite’s global bosses were fully convinced that exiting these markets was the right thing to do. So, when Tainwala made an offer that seemed workable, Samsonite stayed put.

But the biggest change in the company’s strategy came around 2002, incidentally thanks to an innocuous dinner conversation Tainwala had with a friend, whom he was meeting after years. ‘You make washing machines, don’t you?’ asked his friend, who, for some reason, had assumed that Tainwala worked for Samsung. The friend’s reaction to being told that Tainwala, in fact, was working with Samsonite was even more startling. “‘I did not know that the company sells locally’ was his reaction,” recalls Tainwala.

That observation proved to be a big insight for the-then COO of Samsonite India. “Consumers knew the brand, so we just had to ensure that they could buy it. Till then, the Samsonite brand was available only with third- and fourth-grade retailers,” he says. In fact, Tainwala claims that retailers were offered higher margins by competition for not selling his company’s brand. “Not surprising, then, that our brand was sold in just 40 retail outlets across six major cities in India,” reminiscences Tainwala.

That observation proved to be a big insight for the-then COO of Samsonite India. “Consumers knew the brand, so we just had to ensure that they could buy it. Till then, the Samsonite brand was available only with third- and fourth-grade retailers,” he says. In fact, Tainwala claims that retailers were offered higher margins by competition for not selling his company’s brand. “Not surprising, then, that our brand was sold in just 40 retail outlets across six major cities in India,” reminiscences Tainwala.

That’s when Samsonite took the crucial decision of opening company-owned stores. In mid-2002, two Samsonite stores were opened: one in Mumbai’s suburb of Santa Cruz and the other in Dhanbad, in the newly carved out state of Jharkhand. Clearly, there was no sound marketing logic to the choice of the completely dissimilar locations. “A friend had a store in Mumbai that he was looking to lease out. Since I hail from Dhanbad, someone was willing to give me a good deal on some space,” says Tainwala with a smile.

But the move paid off. Samsonite had never clocked business in excess of ₹12 lakh per month across Mumbai before. “The Santa Cruz store alone brought in ₹6 lakh, while Dhanbad grossed ₹2 lakh from zilch,” says Tainwala with childlike enthusiasm. That was the cue the company was looking for and over the next one year, Samsonite opened 100 stores across 20 cities in India. By the end of 2004 (the company follows a December-ending financial year), Samsonite was a ₹50-crore company in India and churning out a profit as well. “It turned into a crown jewel in the global business. We had an operating profit margin of 15%, which is at 20% today,” he explains.

Suddenly, a lot of things fell into place and things started looking better. According to Tainwala, it makes little sense to have a third party between the company and the consumer. “Every retailer, be it Walmart or Macy’s, believes that it is bigger than the brand it sells. That is never in the best interest of the brand,” he quips. A big Bollywood fan, he draws a parallel from the entertainment industry to illustrate his point. “Large producers like Yash Chopra and Karan Johar saw a big opportunity in distribution and opened offices across the world to capitalise on this. They got the best deals with exhibitors and ensured their brand made big money,” says Tainwala. And that has definitely contributed to Samsonite’s progress in India. Today, Samsonite’s decision to go it alone in retail has given birth to a ‘India business model’ within the company. “We did exactly the same thing in both China and Brazil and we met with great success,” says Tainwala, who is understandably proud. While the company got its distribution strategy right, the big boost in sales came when it launched American Tourister.

The Yankee effect

When market research and business consultant IMRB presented its findings to the top management at Samsonite in India in 2006, there was good news and bad news for the company. In the premium segment, which was priced at over ₹6,000, Samsonite held a 100% market share with its Oyster brand. The bad news was that the mid segment (starting at ₹3,000) was dominated by VIP and this was the section showing accelerated growth. “It was clear to us that we had to be in this segment if we wanted to go beyond being just a ₹50-crore company,” says Tainwala. VIP, by then, was a ₹327-crore behemoth and practically accounted for the entire organised luggage industry in India, with Safari as a distant competitor at ₹46 crore.

Tainwala had a chat with Samsonite CEO Marcello Bottoli, who had joined the company in March 2004 after a stint with Louis Vuitton Malletier, and suggested that Samsonite sell luggage in a lower price band. “I was uncomfortable with the idea since stretching a brand seemed very risky,” recalls Tainwala. Given that a presence in this segment was mandatory, he quietly got two brand names — Atithi and Swagat — registered for the mid segment, only to realise at a later date that there was no need to take this step.

The reason? In 1993, Samsonite had globally acquired American Tourister, a brand that sold only in the US and in which the company had no actual interest. “In the US, both the brands were in the same price band. Samsonite bought it to kill competition and buy market share,” explains Tainwala. In India, Samsonite wanted to extend its price points and decided to reposition American Tourister as an affordable brand and launch it here. “That was the second turning point in our history,” he laughs.

The reason? In 1993, Samsonite had globally acquired American Tourister, a brand that sold only in the US and in which the company had no actual interest. “In the US, both the brands were in the same price band. Samsonite bought it to kill competition and buy market share,” explains Tainwala. In India, Samsonite wanted to extend its price points and decided to reposition American Tourister as an affordable brand and launch it here. “That was the second turning point in our history,” he laughs.

American Tourister’s 2007 launch was not without its share of challenges: Tainwala had to convince his bosses that the brand could make money in India without having to compromise on quality. The question was: how? The team in India spent a lot of time looking at VIP’s products in this segment. “The wheels and handles were not too great but the fact is that consumers never had a choice. This was the only brand they were aware of,” he says. A little more probing and endless conversations with folks in the trade provided the answers to many questions. “Consumers were looking for an alternative to VIP and that was the opportunity we had. However, we still had to figure out costs,” recalls Tainwala. Research indicated that Indians wanted good wheels and sturdy handles. “They did not care too much for pockets. It was clear our brand would be without bells and whistles,” he says. By this time, duty structures had been rationalised and it made sense to import American Tourister from factories in China. Tainwala and his team first analysed Samsonite’s handles, which, till then, were made of leather. “We tried a PVC handle that worked. It was synthetic leather and was perfect for the Indian tropical climate.” Then, the interiors were fine-tuned. The Samsonite traveller was an organised person, who liked slots for his shoes and shirts. “In India, however, it was normal to pack one’s shoes in a plastic cover. We also added a little stomach to the bag to give it an expanded look, which Indians love,” he says. The objective was to knock off the frills and still have a product that looked great. In case of wheels, for instance, the team knocked off the decorative axle, without compromising on the product. “We subjected the brand to relentless torture in our simulated environment in Nashik and it survived,” he adds with a grin. The results were there for the world to see.

More importantly, the market was slowly veering towards soft luggage, which worked to American Tourister’s advantage. An industry veteran who has known Tainwala for many years credits him with spotting the change in trends from hard luggage to soft luggage. This coincided with air travel taking off in a big way. “Soft luggage became a product of convenience that was light and looked good as well. This was the phase when consumer preferences were changing, supported by higher income levels, and Tainwala made the most of it,” he explains. Concurring with his view is EP Suresh Menon, CEO, Samsonite South Asia. Pointing out that young consumers were quick to adopt colours such as orange and pale green, he says, “Till then, black was the preferred colour of choice. Now, accounts for only 30% of American Tourister’s sales.” The changing trend was confirmed by the trade. Kanti K Rambhia, who runs 30 luggage retail outlets in Mumbai, says 80% of all luggage sold five years back was in black. “Today, it is barely 30-35%, with consumers choosing fluorescent colours as well. There is a trend of people changing their luggage every year, compared with once every three years in the past,” he adds.

Tainwala derived these keen insights from observing the world around him. “It was apparent that things were changing everywhere and even actors were performing in orange trousers. I just made note of such trends and put them into practise.”

Tainwala derived these keen insights from observing the world around him. “It was apparent that things were changing everywhere and even actors were performing in orange trousers. I just made note of such trends and put them into practise.”

Equally important in the case of American Tourister was to get the communication right. The brief to the ad agency, was clear — to position the company as an international brand. “VIP was known for its durability and we wanted to talk about our durability as well,” says Tainwala.

The TVC depicted a British tourist boarding a crowded local train in Mumbai while trying to keep his American Tourister suitcase safe. “We consciously decided not to mention Samsonite anywhere and the strategy paid off,” says Tainwala. According to Tainwala, the mention of the word American in the brand name worked and the brand was able to command a 10% premium over competition (around ₹3,300, compared with ₹3,000 for VIP), making it a cool product to use.

The net result: in 2008, on a turnover of ₹200 crore, American Tourister brought in around ₹150 crore, with the Canteen Stores Department (CSD) accounting for half of the sales. Even today, American Tourister remains the top draw, accounting for 77% of ₹647 crore sales clocked in CY13.

Catching competition unawares

It took a while for VIP to realise the changing undercurrent in the luggage market and it was not until 2010 that the company got its act together in the soft luggage segment. “This was a new technology and they had to acquire the skills for it. In that sense, VIP lost some time,” says the industry veteran. Barring Skybags, a soft luggage brand that accounted for barely 15% of its sales, VIP’s portfolio predominantly comprised hard luggage. In 2010, VIP relaunched Skybag in the mass market segment and today the soft luggage brand accounts for 20% of its turnover.

Even today, American Tourister, which sources 80% of its products from outside India, derives 85% of its business from the soft luggage segment. In case of Samsonite, this segment brings in 60% of revenues. On the distribution front, Samsonite retails at close to 2,500 outlets across India. VIP’s brands sell in about 4,500 outlets.

A debate over who the overall market leader is or, for that matter, who rules the mid-range market has been on for a while now. If Menon claims that his share of this segment is at least 50%, Radhika Piramal, managing director of the ₹975-crore VIP Industries, is equally insistent that her company accounts for 70%. While Piramal agrees that the competitive landscape has changed dramatically in last 5-10 years, with international brands becoming more serious about the Indian market, she refutes losing ground to Samsonite. “VIP has successfully maintained market leadership despite intense competition from international brands. The reason that consumers continue to prefer our brands is that we offer best-in-class quality, design and features within each price segment,” elaborates Piramal. With American Tourister as its flagship brand, Samsonite’s turnover has grown from ₹243 crore in 2009 to ₹647 crore in 2013. It has already clocked ₹397 crore in the first half of 2014 and is on track to touch ₹800 crore by the end of the year. Though Samsonite is growing comfortably, there is one piece of the entire luggage market that Tainwala is keen to possess but has been unsuccessful thus far.

A debate over who the overall market leader is or, for that matter, who rules the mid-range market has been on for a while now. If Menon claims that his share of this segment is at least 50%, Radhika Piramal, managing director of the ₹975-crore VIP Industries, is equally insistent that her company accounts for 70%. While Piramal agrees that the competitive landscape has changed dramatically in last 5-10 years, with international brands becoming more serious about the Indian market, she refutes losing ground to Samsonite. “VIP has successfully maintained market leadership despite intense competition from international brands. The reason that consumers continue to prefer our brands is that we offer best-in-class quality, design and features within each price segment,” elaborates Piramal. With American Tourister as its flagship brand, Samsonite’s turnover has grown from ₹243 crore in 2009 to ₹647 crore in 2013. It has already clocked ₹397 crore in the first half of 2014 and is on track to touch ₹800 crore by the end of the year. Though Samsonite is growing comfortably, there is one piece of the entire luggage market that Tainwala is keen to possess but has been unsuccessful thus far.

Mass problem

While Samsonite has been able to retain its hold in the premium and mid-range luggage segments, it has been unable to crack the value segment — ranging below ₹3000 — where VIP still calls the shots. Samsonite launched a new brand, AT, an abbreviated version of its more popular brand but the strategy backfired. According to Tainwala, AT was a new brand but consumers viewed it as American Tourister. “Channel partners, too, were selling it as American Tourister. It was a big mistake,” he explains. According to Menon, the problem with AT was that the brand did not meet consumers’ expectations on quality. “There was only so much we could offer at ₹2,000 and the consumer though he was buying a product similar to American Tourister. There was a clear mismatch,” he elaborates.

A presence in the mass segment is necessary for Samsonite to widen its product portfolio and accelerate growth in India. Consider this: the organised luggage market is only ₹2,000 crore, while the unorganised market is ten times larger. “We will need to take the tougher route of creating a new brand. That won’t be easy but it needs to be done,” says Tainwala, who estimates that it will cost at least ₹20 crore each year for three years for the company to get there.

Making a difference

Shift in distribution strategy is paying off

Given how similar the markets are, Samsonite is planning to test the Korean and Chinese markets for low-priced luggage this Christmas. “Even if it does not work, we will go back to the drawing board to correct it. According to my estimates, we will enter India with the new offering some time in 2016,” he says. Incidentally, AT was also launched in China two years back and had met with the same fate.

There is sound logic behind not introducing the new brand in India. “We have a rule in the company about not taking up more than one new initiative every five years,” says Tainwala. In India, the company has just launched High Sierra, a back-to-school backpack. The overall backpack business in the Indian market brings in 12% of revenue for Samsonite, while another 5% comes from accessories.

The company globally acquired the High Sierra brand in July 2012 for $110 million. A couple of days later, Samsonite bought over Hartmann, a luxury luggage brand, for $35 million. “High Sierra is a highly profitable brand and we have launched it in other markets as well,” says Tainwala. In case of Hartmann, the plan is to grow slowly and start only a couple of stores. “It is priced at over $500 in other parts of the world but the market is limited here,” he explains. Other players in that segment include Tumi, Louis Vuitton and Rimowa.

However, Samsonite does not see any immediate challenge to its hold on the top end of the market. The bigger plan is to give VIP a run for its money in the mid-range segment and, at the same time, figure out a way to make sense of the mass segment. But Tainwala will need to contend with a bigger market and the fact that, despite some similarities, customer preferences vary across these markets.

Take High Sierra, for instance. Acquired two years ago, the brand was launched simultaneously in India, Germany, Korea and Scandinavia. In India, the brand took off, with customers loving the American look. In Germany, customers find the design clumsy and are questioning its functional value. In Korea, the brand has been a disaster because people want minimalist design, while the response has been lukewarm in Scandinavia. But Tainwala is up to the challenge. “It is not easy to understand the mind of the consumer. We do not get it right everytime; we only try and get better at it,” he sums up.

Just one email a week

Just one email a week