While watching historical films that chronicle the events of 1947, have you ever wondered what happened to all those beautiful houses or the massive corporate buildings that owners just left behind while fleeing for their lives? They became “enemy” property, in the hands of our government. The Indian government appointed The Custodian of Enemy Property to control all the assets once owned by Indians, who emigrated to Pakistan or China. So, in April 2019, when the Custodian sold 44.3 million “enemy” shares to PSU insurance companies, it seemed a bit ironic as — on one hand the government was divesting “outsiders” assets to shore up revenue and on the other Western India Palm Refined Oil was laying out the welcome mat to foreigners, for the same reason. In May 2020, the Bengaluru-headquartered company announced that Thierry Delaporte, a Frenchman will be taking over from Abidali Neemuchwala in July. The Capgemini veteran will be the first non-Indian CEO of an IT major, where more than 90% of the ownership is in the hands of Indians, including over 74% held by the promoter family. An “outsider” himself, Neemuchwala resigned in January after leading Wipro for five years, trying to break a spell that had gripped the tech major during the financial crisis of 2008.

Long winter

The recession was tough on every Indian IT company. From growing at over 30% annually for three years until the crisis hit, Infosys, TCS and Wipro collapsed into the mid-teens for the next three. Most could shake off the slump only by the end of the decade. Wipro wasn’t one of them. While its competitors such as Infosys and TCS were building business models geared towards exposure of over 35% to the worst hit — banking and financial services (BFSI) — sector, Wipro had only 26%. What it did not anticipate was how quickly the financial services sector would invest in IT solutions. This time, with a greater focus on risk management and regulatory compliance. “The energy and utilities (ENU) vertical, where Wipro had considerable exposure, saw the slowest recovery and even in BFSI, Wipro’s portfolio was oriented towards capital market clients,” points out Abhishek Shindadkar, IT services, internet and telecom analyst at Elara Capital.

2008 was a watershed year for Wipro in another way as well. After three years as acting CEO, promoter and chairman Azim Premji appointed joint CEOs Girish Paranjpe and Suresh Vaswani. Many industry veterans and analysts place the blame for Wipro’s continuing woes squarely on this dual-CEO structure, which continued till 2011. “The joint CEO model was unworkable because a ship cannot have two captains. This structural mistake led to the downfall of the company,” says Sudip Banerjee, a 25-year veteran of Wipro who quit as president of the company’s enterprise solutions division in 2008 to head L&T Infotech. A Mumbai-based analyst who did not wish to be named seconds that. “Companies with two power centres cannot function well. In a way, that divided power system continues even today because while those leaders may have left Wipro, the structures they built and the politics that go alongside remain,” he points out.

Even after the joint leadership structure was let go,the company saw a very hands-on role by the promoter family. Premji stepped down as executive chairman in July 2019 and will continue on Wipro’s board as non-executive director for another five years. His son Rishad Premji, who was the chief strategy officer, has succeeded him as chairman. The alignment between the promoters and the CEOs has not always been the best, say analysts, which makes the latter reluctant to initiate any change that may not work out as planned. “There’s reluctance to take bad news back to the promoter, to take tough calls, to let go of old-timers who aren’t adding value,” says the analyst. The result, then, is a stodgy organisational culture that is slow to embrace change. Wipro when contacted refused to participate in this story.

But it is not as if Wipro has spent the past decade waiting for a knight in shining armour. On the contrary, TK Kurien (CEO from 2011 to 2016) and his successor Neemuchwala have done much to change the organisational culture, explore new business avenues and pivot from low-margin, traditional IT services to digital services.

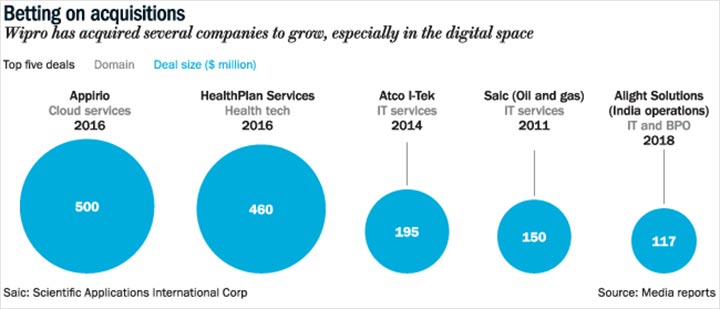

Kurien took the first step to making Wipro less paternalistic and hidebound by reducing the number of people reporting to him, bringing in younger vertical heads, giving them more decision-making power and linking leaders’ salaries to performance and team attrition. He also kicked into high gear Wipro’s string-of-pearls acquisition strategy, snapping up Scientific Applications International Corp’s (Saic’s) oil and gas practice for $150 million in 2011, Atco I-Tek for $195 million in 2014 and DesignIT for $94 million in 2015, among others (See: Betting on acquisitions).

When Neemuchwala took over in 2016, he proved to be as pro-acquisition as his predecessor. Wipro has closed about 10 deals in his tenure, running up tabs ranging from $8.5 million for design firm Cooper in 2017, to nearly $1 billion the previous year for Appirio and HealthPlan Services. He also recognised that the IT industry was at an inflection point where, explains Everest Group CEO Peter Bendor-Samuel, “the third-party services industry shifted from mature labour arbitrage factory model to digital projects”. Accordingly, Neemuchwala pushed Wipro into the digital services space and revenue from digital grew from 24.6% in FY18 to 40% in FY19.

The outgoing CEO also split the India and West Asia business into two separate divisions under new heads and later, reorganised the India business by separating public sector and government businesses. Last year, Wipro also sold two of its cloud-based personnel resource solutions — Workday and Cornerstone OnDemand — to one of its biggest clients, the US-based Alight Solutions, for $110 million. The strategy was straightforward — streamline the business and shift focus to high-growth, high-profit digital areas. “Neemuchwala managed to transform Wipro towards more outcome-centric and transformation-led growth. His strategy was towards long-term sustainability and to quickly transform Wipro’s growth from traditional to more digital focused,” says DD Mishra, senior research analyst, Gartner India.

But the company’s high exposure to troubled verticals such as healthcare and ENU remained, proving to be a drain on profitability. “About 70% of the portfolio is growing as per industry standards. The remaining, legacy businesses of support and low-end IT, has been denting growth,” explains Amit Chandra, IT research analyst, HDFC Securities. Wipro’s weak areas, he adds, were the India and West Asia business, the ENU vertical and infrastructure management services (IMS), where the company “faced pricing pressure, client exits and loss of revenue from not renewing contracts”.

One of its big bets went wrong when it acquired Atco in 2014 to focus on energy since crude oil price was at $80-100/barrel. Six months later, it slipped to under $50/barrel and Wipro’s revenue from ENU was in jeopardy. “Some poor acquisitions or poorly-timed acquisitions in IT infrastructure, healthcare and others created a drag on growth and diverted resources and leadership attention,” points out Bendor-Samuel.

Similarly, the scrapping of Obamacare in 2017 came as a huge blow for its US-based subsidiary HealthPlan services, and volume in the healthcare vertical (13% of total revenue in FY20) plummeted. From $223 million revenue during the year of acquisition, it fell to $192 million in FY18 and $146.5 million in FY19. “Nobody could have anticipated that change. Healthcare was supposed to be a big driver of growth for the next few years. Life-sciences and healthcare services portfolio is likely to do well,” says Shindadkar. “There is room for improvement in both sales and delivery at Wipro, in terms of client mix as well as mining,” he adds cautiously.

New innings

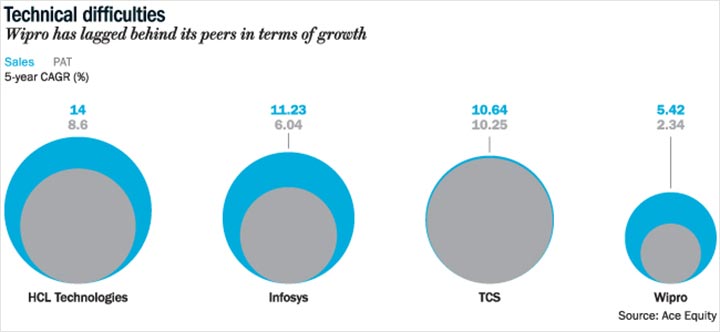

Once again, Wipro stands at a crossroad with a new leader at the helm. The company has been underperforming its IT peers for several years now, growing sluggishly in single digits (See: Technical difficulties). And as the gap widened between Wipro and market leaders TCS and Infosys, it lost its third position to HCL Tech in FY19. The stock price mirrors this lacklustre performance — in the past five years, the Wipro stock has risen 8%, while the top three companies — TCS, Infosys and HCL Tech have increased by 65%, 47% and 31%, respectively. If Wipro is to recover and get back on track, the new CEO will need to aggressively change business operations and strategy and take some tough calls. Can Delaporte help Wipro get back its mojo?

The timing could not be more challenging. COVID-19 has disrupted the global economy in unprecedented ways and the impact is already showing across diverse sectors and industries, including IT. Even though the lockdown and business disruption started only in the second half of March, the numbers for the quarter showed the strain. Wipro’s IT services revenue declined 1% QoQ and 0.1% YoY to $2.07 billion, led by negative impact of $15 million-16 million (0.7-0.8% of revenue) due to COVID. And for the first time in 20 years since it listed on the NYSE, the company did not give guidance for the ongoing quarter, citing uncertainty due to the pandemic.

So, what is it going to take for Delaporte to get Wipro back on the rails? Just a little TLC or a whole lot of tough love? More of the latter, by all accounts. He is reputed to be a strong leader and ambitious, with a robust background in operations and finance, all of which will come in handy at his new assignment. The 52-year-old has spent the past 25 years at Capgemini and while he has never worked here, over half of Capgemini’s 200,000 employees are based in India, so Delaporte is not a stranger to the country. Delaporte also oversaw iGate’s integration with the French multinational, after it was acquired in 2015. “He is a master of operating in a cross-cultural environment. At Capgemini, he integrated leading North American, Indian and European firms and that experience will serve him well as he moves into the Wipro culture, which is not used to non-Indian leadership,” says Bendor-Samuel.

Managing the culture difference will be a large part of Delaporte’s agenda. Banerjee points out the immediate challenge for Wipro’s incoming CEO. “He has to understand and manage a very diverse group of people. A majority of customers are in the US and employees in India, which will add another degree of complexity to the situation,” he says. To be sure, Delaporte’s decision to stay put in Paris has raised eyebrows among observers and analysts. While some believe the distance may exacerbate the existing difference of language and culture and intensify the Frenchman’s “outsider-ness”, others see it as a possible advantage going forward, even seeing a timezone advantage with Paris being midway between India and the US. “There is an opportunity for Wipro to win clients from the large European market, which has been measured to outsourcing historically, compared with other developed markets. This is especially a possibility now in an environment of borderless execution,” says Shindadkar. Bendor-Samuel takes a different, but still positive, view. “I would not be surprised if, after some years, Delaporte moves to the US. He used to live in New York and the US market is by far the most important for Wipro,” he says.

The biggest challenge for Wipro is growth, says HDFC Securities’ Chandra, listing out what’s working in Wipro’s favour: free cash generation, four buybacks, stable dividend and margins. “What it lacks is the ability to build and sustain momentum with clients. That is a structural issue. Delaporte comes from a company that is nearly twice as large as Wipro. He can open up new markets, bid for and win long-term contracts, which should bring stability,” he adds. Delaporte is also likely to build on the foundation Neemuchwala has laid in the digital project space. “He is well acquainted with digital skillsets and led the effort to build Capgemini’s digital portfolio, which the firm now uses to drive growth,” points out Bendor-Samuel.

Delaporte’s new assignment would not have been a cakewalk at the best of times. Now, his task looks positively Sisyphean. COVID-19 has changed the way the world works and does business, perhaps for ever. The old rulebooks have been tossed aside and, so far, no one is sure what the new rules of engagement will be. Certainly, belts have already been tightened around the globe, businesses have gone bust and there is likely to be an avalanche of budget cuts, pricing pressure, restructuring of spends and requests for discounts.

There could be an opportunity here for new business. Bendor-Samuel points out the pandemic is accelerating the shift to automation and other digital technologies, since companies can realise cost savings of 40%-60% when they modernise fully.Given that a potentially prolonged recession seems inevitable, companies are understandably seeking to reduce costs, “making digital-at-scale modernisation activities nearly irresistible”.

Others are not as optimistic. Chandra does a quick analysis of Wipro’s business by verticals. He believes the outlook is weak for BFSI, retail, travel, hospitality, manufacturing and ENU, but it is positive for consumer, utility, communication, new age media, high tech and healthcare (exclusive of HPS). “That’s more than half the business with a weak outlook. How do you expect growth to pick up, especially with COVID?” he asks.

Wipro needs to improve its messaging and strengthen local account management teams to drive better experience with customers, declares Gartner’s Mishra. “While doing so, Delaporte is going to face tough competition in the market from smaller players, revenue cannibalisation, the post-COVID slowdown of demand and aggressive expectation of clients in a crowded market. Navigating Wipro through current uncertainties is not going to be easy,”he explains.

So, can Wipro turn around? Will Delaporte prove to be the architect of that transformation? Banerjee says wryly, “My heart says yes. My head is not so sure.”