When the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) announced its decision to withdraw Rs 2,000 notes from circulation on May 19 this year, it brought about a sense of déjà vu, reminding everyone of the chaos and panic that had gripped the country in 2016 when the government demonetised Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes. However, experts and economists have dubbed the current move “inevitable”.

In its release, the RBI stated that Rs 2,000 notes had been introduced in November 2016 primarily to meet the currency requirement of the economy in an expeditious manner after demonetisation. That objective was served once notes in other denominations became available in adequate quantities. Subsequently, printing of Rs 2,000 notes was stopped in 2018–19.

“Rs 2,000 notes were introduced as a temporary measure in 2016. You needed some currency to re-monetise the economy quickly. The decision to withdraw is not shocking; it was very much on the cards,” says Madan Sabnavis, chief economist, Bank of Baroda, adding, “This time, this is done in a sensible manner, as ample time has been given [for the exchange of notes].”

‘Not a Big Deal’

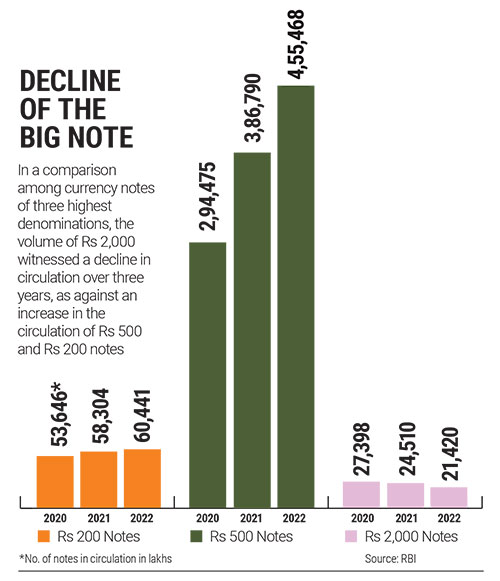

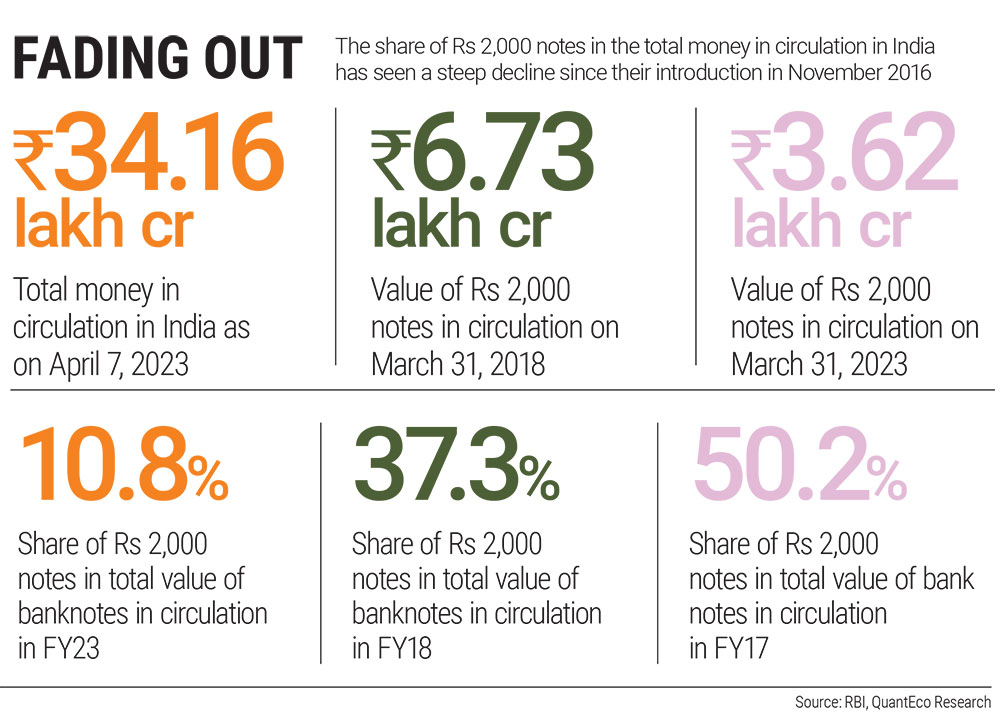

According to the RBI data, the total value of Rs 2,000 notes has declined to Rs 3.62 lakh crore, or 10.8% of the notes in circulation, on March 31, 2023, down from Rs 6.73 lakh crore, or 37.3%, on March 31, 2018. The circulation of these notes was at its peak in 2017—the year after demonetisation—when it made up 50.2% of the total value of bank notes in circulation, according to QuantEco Research, an economics research firm.

Economist Arun Kumar does not attach much significance to the RBI announcement. “The value of Rs 2,000 notes [in circulation] was already coming down in the economy, from Rs 6.73 lakh crore in 2018 to Rs 3.62 lakh crore in 2023. Had the government waited for more time, it would have automatically reached even lower levels without it withdrawing the notes.”

Former finance secretary D.V. Gopalan calls it a routine exercise. “In 2013 also, Rs 500 notes issued prior to the year 2005 were withdrawn as they had fewer security features. This is absolutely normal,” he says. According to him, since Rs 2,000 notes were introduced in haste to remonetise the economy, they might have fewer security features, which made their withdrawal an event that was “supposed to happen”.

Curb on Black Money

There are multiple reasons being speculated for the withdrawal of the denomination. Some of these contradict the ones that had been given by the government for demonetisation in 2016. One of them was curbing black money. Back then, the government had argued that the demonetisation move would extinguish the black money stashed away by the wealthy. However, the RBI data showed that over 99% of the money that had been taken out of circulation had returned to the banking system, extinguishing the government’s optimism instead.

“People still hoard big denomination currency like Rs 2,000 to buy jewellery, gold, etc. After the Covid-induced lockdown, hoarding of big denomination is also [done] from the security and emergency perspective,” says Sabnavis. He is of the opinion that introducing Rs 2,000 note was a “big error” and doing away with Rs 1,000 notes was “an absurd decision”.

Subhash Chandra Garg, former finance secretary, says that Rs 2,000 notes were susceptible to black money dealings and the decision to get rid of them is directed at to curb black money.

However, former chief statistician of India Pronab Sen is not convinced that withdrawing Rs 2,000 will help in curbing black money. “Post-pandemic people are not sitting on the cash. Black cash never sits idle; it gets converted into black assets. I do not think that this will have any impact on the black money. This is relatively smaller amount now.”

In December last year, Sushil Kumar Modi, member of Parliament from the Bhartiya Janta Party (BJP) in the Rajya Sabha, had demanded during the zero hour that Rs 2,000 be phased out gradually as it encouraged black money and hoarding. He also gave the example of many advanced countries using lower denomination currency notes. “In the US, $100 denomination currency is the highest. In China, the 100-yuan denomination currency is highest. In the European Union, it is €200. In contrast, countries like Pakistan and Sri Lanka have Rs 5,000 as the highest denomination,” he said. Similarly, the European Central Bank discontinued €500 notes in 2018, while Singapore stopped issuing $10,000 notes in 2010 to curb illegal activities, including drug trafficking, money laundering, terror funding and tax evasion, among others.

Sen believes that before jumping to these global examples one should look at relative prices. “One dollar is equal to Rs 80, and similarly, $10 dollar bill in US is Rs 800 in India. India’s high denomination of Rs 2,000 is equal to $25 in US which is less than $100, the highest denomination in the US, so this logic does not hold any currency,” he says.

Kumar, also the author of The Black Economy of India, sees no point in withdrawing Rs 2,000 notes to tackle corruption or stashed money. “If dealing in cash is a determinant of black money and corruption, Japan should have huge corruption, as it has 13% of its GDP being used as cash. On the other hand, Nigeria uses 1.4% of GDP as cash, which should ideally mean that there is minimal or negligible corruption there, but that is not the case,” he argues, adding that in India, cash is 13% of the GDP. “Having more or less cash in the economy has nothing to do with black money; it is a social and cultural practice,” Kumar tells Outlook Business. “If it is done with the view to deal with black money, I think the numbers of hoarders is very less this time,” he adds.

The Denomination Effect

India’s recent move to withdraw Rs 2,000 currency seems to be motivated by the denomination effect. N.R. Bhanumurthy, vice chancellor of BR Ambedkar School of Economics, says that higher denomination has an impact on its circulation rate. He says, “Ever since the demonetisation, we have had large currency in circulation. Large currency has low velocity of circulation. Fundamentally, the currency is meant for an exchange. Here the Rs 2,000 note, which is a high denomination, has almost negligible velocity of circulation. I think this decision is to increase the circulation with low denomination.”

In their 2009 research titled The Denomination Effect, marketing professors of New York University Priya Raghubir and Joydeep Srivastava suggest that people may be less likely to spend larger currency denominations than their equivalent value in smaller denominations. According to them, the denomination effect is especially strong in countries that have predominantly cash-based economies.

Laying Groundwork for CBDC?

Many experts dubbed the RBI’s decision to withdraw the Rs 2,000 notes as a move to pave way for the central bank digital currency (CBDC) in India. “This idea seems a little far-fetched to me as India already has substantially mainstream digital payments and the CBDC is an alternative digital payment mode. It is unlikely to succeed in India as its design is horrible and only experiments have been conducted so far,” Garg tells Outlook Business.

Sen too is not convinced by the argument. He believes that promoting CBDC has to be done gradually and incrementally. “Every year the RBI increases money supply by 12% to 16%. To go for CBDC, the government will not print money but issue CBDC,” he says. Gopalan insists that the withdrawal of the currency is a common practice and that CBDC is not on the radar this time.

Disruptive Impact on Economy

Micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) and the informal sector, including agriculture, were the worst hit during the 2016 demonetisation. With around 85% of the cash in circulation losing validity overnight, the sectors which relied heavily on cash, was left struggling for survival. This time, the withdrawal of Rs 2,000 notes is expected to have short term disruptions for the MSMEs, agricultural sector, etc., but experts differ on the intensity of the impact.

“Since the velocity of Rs 2,000 note is the least, I do not think this time there will be any impact on any aspect of the economy. In my opinion, it is a non-event,” says Garg. “There may be some places where we can see some short-term pain or disruption, like in mandis. But this time it would not be that grave,” says Gopalan. Kumar disagrees. “This decision will have a disruptive impact on the economy, especially small traders, farmers and MSMEs,” he says.

Sen believes that wholesalers will bear the brunt this time, albeit for a short period of time. “I do not think the Rs 2,000 withdrawal will have an impact on MSMEs. This time, the larger impact will be felt on wholesalers and large traders, not small traders. I think mandis will get affected for some time,” he elaborates.

Since Rs 2,000 notes were already on their way out, as Kumar observes, the objective of the government in making a noise about withdrawing it is not clear. Samajwadi Party leader Ram Gopal Yadav claimed that the BJP is trying to divert attention from its electoral defeat in Karnataka. Former Lok Sabha MP from All India Anna Dravida Munetra Kazhagam K.C. Palanisamy alleged that the move is to curtail the opposition`s money power in the Lok Sabha election next year.

Sen has a similar opinion: back-to-back elections in some states and the national election slated to happen in 2024 could be a motivating factor for the government to take this decision.

While speculations abound, the gradual phasing out of the currency note—the government is planning to extend the current deadline of September 20 for their exchange—has diluted the noise around the decision and spared the government some awkward questions.

Just one email a week

Just one email a week