- I owe my success to Destiny

- Strength Honesty

- Your sounding board My conscience

- Most vulnerable moment When sympathy and kindness overtake me

- Insightful proverb Samayamu-sandharbhamu (Ultimately, time and context matter)

- Best advice you every got What you say is less important than how you make the other person feel

- The day you felt really high When I cleared the IAS

- The day you felt very low When my mother passed away

- Morning or a night person Very much an early morning person

- Tea or Coffee Filter coffee

- Best place in the world My home

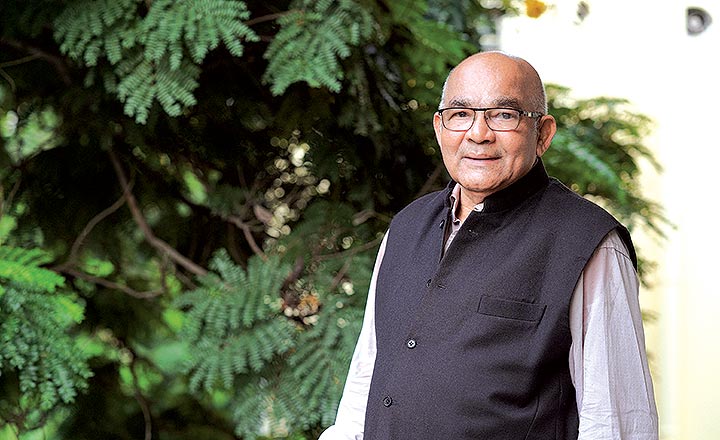

- Describe yourself He loves to live, and he lives to love

My early years were spent in Paturu, a village in Kadapa district. I was born here, in my mother’s house. Our house was located on Kapu Veedhi, the street of Kapus, who were also known as Reddys. If a person of a higher caste or status was around, men had to leave their dhoti unfolded, letting it fall to their ankles. Only with people of their own or lower socioeconomic strata could they fold it up! Also, if people from the scheduled castes had to pass our street, they had to carry their footwear in their hands! Life then was steeped in casteism.

Traditionally in Reddy families, daughters were pampered by the father (ayya), while a son could be in the ayya’s presence only if called for or sent by his mother! But my ayya had always been friendly with me, prompting amma to remark that he was spoiling me by not being aloof enough. His only weakness was for food, especially since amma was an excellent cook. But he had developed a heart condition early in his life, so she attempted to moderate his diet. It was a futile effort — amma would often give in, as ayya would sit for a meal but wouldn’t look at his plate till he was served what he wanted!

My father was remarkably modest for his standing, attributing his achievements to good luck. He would often say that his friends who were more brilliant than him were ordinary teachers or assistant engineers, while he had become a respected officer. In fact, if I used to study in the night or early in the morning, he would say, “Why are you studying late into the night? In life, you should be good but your fate will determine your life.” That was my father’s philosophy, but my mother’s approach was slightly different. She would keep telling me that, if I didn’t study well, I would have to slog in the field like a farmer. That proved an effective threat and I studied hard.

***

I could have joined engineering after school, but since I was underage by a year, I joined a bachelor’s degree (honours) course in economics at Vivekananda College in Madras, in 1957. At the college, many of my classmates were from urban, educated, middle class and upper-middle-class backgrounds and their only aim was to pass the exams to become IAS officers, lecturers, lawyers or at worst, an upper division clerk at the accountant general’s office.

Around this time, leftist political ideologies were gaining ground in the Andhra area, and Periyar’s Dravidar Kazhagam in Tamil areas. I witnessed processions where idols of Lord Ganesha were carried through the streets in Madras, while people shouted angry abuse at the idols and threw slippers at them. At first, I was shocked as Ganesha and other Hindu gods were sacred in my house. I was sympathetic to leftist ideology for a while in Government Arts College in Anantapur (1955-57) and to Periyar’s self-respect movement.

I went on to become the general secretary of the hostel union. As was the practice, distinguished persons would give lectures in the hostel’s prayer room, where pictures and idols of Hindu Gods would adorn the walls.

As the general secretary, I invited Mona Hensman, the principal of Women’s College; Syed Abdul Wahab Bukhari Sahib, of New College; and Kamaraja Nadar, a non-Brahmin Congress leader. Those were exciting days, where I learnt the power of speaking out. But, I also learnt the importance of keeping quiet, and keeping time, on my next assignment.

In 1960, I was admitted into the full-time PhD programme at Osmania University under the guidance of Prof VV Ramanadham (VVR), an expert in transport economics and economics of public enterprises. I learnt quite a few things from him. He would often give appointments at odd times — 9:05 am or 8:55 am, but never 9 am. His explanation was that in India, 9 am meant about 9 am, stretching all the way to 10 am. But with 8:55 or 9:05, there was no mistaking the seriousness of the intention! Also, his room had two cards: one on the wall that had a picture of a fish about to bite a hook and underneath was a quote, “Even a fish could avoid trouble if it kept its mouth shut.” The card on the table read “Your time is precious, don’t waste it here.” The message was clear — be punctual, open your mouth only when essential, and get out when the job is done. I learnt them well.

In August 1961, I was appointed as a temporary lecturer in Hyderabad Evening College. My term was six months and my consolidated salary was #250 a month. After a month, I was transferred to the prestigious Nizam College, whose students were from the upper echelons of society.

I was nervous on my first day as the class was overflowing with young men and women — all my age. After introducing myself, I expected questions on my teaching style, economic concepts or previous work experience, from the students. But that was not to be. “You were working in the night college before joining here. What were you doing during the day?” came a question, amid muffled laughter. Knowing the slant of the question, I, too, cheekily replied: “In day-time, I did what others do during nights!” There was laughter all around. After some more banter, the ice finally thawed. A few months into the job, I was to lead an excursion to Delhi. I agreed on the condition that the trip would have no girls. But the principal said girls would be part of the troupe. “But”, he added, “the girls have assured me that they have self-control and that you should not worry.” I assumed he meant they would behave themselves but I retorted, “Sir, I cannot assure you about my self-control.” My days as lecturer didn’t last for long though.

***

Ayya wanted me to pursue civil services and since his health was deteriorating, as the older son, I would have to take on greater responsibilities at any moment. My work at the college was great and my salary was good. But I saw his point: civil service offered stability and respectability during uncertain times. I decided to prepare for it, but I was determined to pursue my interest in academics. Prof VVR was not comfortable with my decision as he wanted me to apply for a post-doctoral research fellowship at Stanford University. He spoke to my father, but ayya was firm. In fact, the vice-chancellor, too, tried to dissuade me by saying: “You are old enough to think for yourself.” I replied, “Yes, I thought for myself and decided that I will obey my father!” That was how I moved on to becoming a civil servant.

Unfortunately, ayya didn’t live to see the day I was selected, but by then I had only taken my written examination. After ayya’s death, we had to vacate our government quarters. We sold our Fiat car and I had to buy a bicycle. Our standing in the society, though, was restored by June 1964, when I joined IAS and was deputed to Andhra Pradesh.

***

Initially, I was posted as an assistant collector under training in Visakhapatnam district. It was a good initiation into the rough and tumble of administration, as within a few days, I was assigned to adjudicate an irrigation dispute and write up a draft award on the collector, Abid Hussain’s behalf. I was surprised when the collector signed the draft without reading it. It was my first learning in management — Abid sir told me it was my objectivity as a complete outsider to the dispute that was more important than knowledge of the subject or of the law. Another advice he gave me was that you do not have to be anti-rich to be pro-poor.

My training period in the state was a choppy affair, from July 1965 to April 1967. I had the rare distinction of being transferred four times during that period! My first move was to Hyderabad district. As a block development officer, I had my first encounter with corruption. The panchayat samiti president was close to a minister. He had obliged bureaucrats by helping them buy land, including laying roads to their grape gardens or farms as part of the government rural roads programme! Pocketing 10% in cash was a precondition for issuing any cheque to the public from any state scheme. I tried to put a stop to the practice. My next posting was as secretary, zilla parishad, Chittoor, where I lasted for four months. A day before I was to take over as sub-collector and magistrate in Rajahmundry, I was posted to Ongole subdivision. But the person in charge did want to move out of his posting and refused to hand over the charge. “I want you to go to Hyderabad and get it cancelled because I want to remain here,” he told me. I replied: “Do me one favour — get it cancelled and I will hand over the charge. I am prepared to go anywhere but spare me the agony of not having a job till then.” So, he handed over the charge to me and went to Hyderabad for a week. He came back but was posted to a neighbouring sub-division. So, one of the lessons that I learnt is that if somebody is unpleasant to you or something bad happens to you, you are not necessarily the reason why it is so!

Thankfully, I got a break from my posting in Ongole as my application for a diploma course in planning at the Netherlands-based Institute of Social Studies (ISS) was accepted. I was excited as I was going abroad for the first time and, more importantly, would be studying economics, a subject that I loved. My days at the institute were sheer bliss. Lectures were held in spacious classrooms that overlooked elegant gardens with ponds and fountains.

The ISS was also an eye-opener, academically, culturally and socially. I was impressed by the openness of the society. Soon, I began to understand the difference between friendly girls and girlfriends!

***

When I came back to India in July 1968, I was posted as a sub-collector at Gudur, and it was around this time that I got married. On official tours, I would pack two boiled eggs in the left pocket of my jacket and two pieces of toast in the right pocket. That way, I was not obliged to anybody in the village for my lunch! The image of impartiality and being pro-poor is important in rural India.

Then in Guntur, I was the district revenue officer for a few months in 1969, and my focus was on establishing the land rights for the poor. In the absence of a legal recourse, poor farmers often occupied community lands for which they had no pattas (right to cultivate). Instead of waiting for individual farmers to approach us, I organised an official apparatus to go to every village, urging farmers to petition their claims on the lands they had been cultivating. They were given temporary pattas that could be later made permanent. My initiative also got a boost when I requested President VV Giri, who was travelling through Guntur district by train, to hand out pattas to poor farmers at the station! A former trade union leader, Giri readily agreed. Incidentally, on October 2, 1969, when Gandhi’s centenary celebrations were being conducted under my overall guidance, the irony was that prohibition got abolished in Andhra Pradesh on the same day!

While I was respected as a very good officer, I was also perceived to be “difficult”. I was happy to take up the job as deputy secretary in planning as I got to be close to my family and also ended up working in the field of applied economics, something I had been waiting to do ever since my course in Netherlands. So, being difficult did have its rewards.

For a few months, from September 1973 to April 1974, I was posted as collector and district magistrate at Nalgonda. Around this time, I once had to accompany chief minister Vengal Rao to Yadagirigutta temple. Protocol required me to accompany the CM. But at the entrance of the temple, I told him that I would not enter it. The CM was surprised but did not raise any objection. While I was not devout, I had stopped believing in God and going to temples after my younger brother’s untimely demise in 1970. I waited at the guest house close to the temple when, suddenly, I began questioning my stance. How could I be so sure that God did not exist? In any case, if I did not know anything with certainty about God, how could I be an atheist? So, I decided that if I was unsure, then I would not be averse to God, or puja, or temples. Since then, I have visited the temple many times over in subsequent years.

Almost 15 years after I was admitted to the programme, I got my PhD in March 1975 from the Osmania University. After joining the IAS, I had fulfilled my ayya’s dream, and after I got my PhD, I felt I had fulfilled my own. In 1976, I was appointed as the collector of Hyderabad district. However, I was not keen to take on the job and even mentioned it to CM Vengal Rao about it. But he said, “I want you. You need not succumb to pressures. All you need to do is listen to ministers and do what is fair.” That sounded reasonable, but I got cheeky. “Sir, suppose you make a request? What should I do then?” He replied, “You need not do anything that you do not think is fair or correct, but you refer the matter to the government and we will decide!”

Once, during my tenure as collector, I was told to receive Sanjay Gandhi, the son of prime minister Indira Gandhi, at the airport. Since he had no official position, I told the CM that it would be inappropriate as a collector to receive someone who had no official standing. To avoid any embarrassment, I offered to proceed on leave. As I was leaving the room, the CM remarked: “I wish I could go on leave as well!”

I did not cease to be difficult, and in April 1977, I was moved, despite my reluctance, to the Centre as deputy secretary in the department of economic affairs (DEA), at the finance ministry. I was to be on the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank (WB) desk, which was a prestigious posting that several had vied for. As a result, my colleagues in the department viewed me with wariness. Only Dr Manmohan Singh, secretary of economic affairs, who had pushed for me to be given this posting, greeted me with great warmth. Following the adage, “Even a fish could avoid trouble if it kept its mouth shut,” I kept my trap shut and chose to read, listen and learn. Three months later, I was comfortable in my role. On occasions, Dr Singh would ask me to examine files that did not concern my desk.

I was lucky to get the job of technical advisor to the executive director of the WB in 1978 as Dr Singh once again proposed my name. When I received the orders to join the WB, I thanked Dr Singh. He said, with his usual, quick smile, “You don’t have to thank anybody. You deserve it. In fact, it was delayed by a bit, that’s all.”

I was assigned to work under (Maidavolu) Narasimham, the Indian executive director in the World Bank. He initiated me into the basics of global finance. A former governor of the Reserve Bank of India, he had a razor-sharp mind and inexhaustible energy and network. Despite attending two to three cocktail parties followed by dinner, the next morning he would walk into the office, fresh as a daisy! After a year, Narasimham left the bank to join as the IMF as the Indian director.

Narasimham’s successor was HN Ray, a gentleman known for his integrity, but he wasn’t adept at handling US-style negotiations and functioning. This would often result in contrary views. Though he treated me as a son, I am ashamed to say that I, perhaps, was arrogant. Once, during a disagreement, Ray protested at my style of arguing. “Dr Reddy, I joined the civil services before you were born. Learn to show some respect.” I replied, “Sir, I will show my highest respect at your home, but in the office, if I feel you are wrong, I have to say it.” In spite of my attitude, Ray requested for my services to be extended from the original three years to five years.

While I officially did not participate in negotiations on behalf of the government of India, as I was, technically, an employee of the World Bank, I would often guide the Indian delegation. The WB was also comfortable with my help and I would be informally invited to parties strictly meant for Indian delegates and the WB negotiators. During one such negotiation, the bank was insisting on a particular condition that the Indian team was not authorised to concede. The team asked me to intervene as they felt the loan was essential and wanted me to advise the government to agree to the condition. Even though the loan was essential for us, I understood the government’s point. I told the Indian team that my advice was that they break the negotiations and head back to India the next morning. As expected, the bank authorities contacted me to explain their position. I informed them that the negotiations were off and that the Indian team had booked their return tickets for the next day. Hearing that, the WB team, after hurried consultations, informed us that they had changed their mind and they would not insist on the condition.

Once, a senior World Bank official asked me the secret of my negotiating success, I replied: “I am a Hindu. If we commit a sin, we can do ‘prayaschit’ or prescribed atonement, so we believe everything is negotiable. If we cannot complete a task in this lifetime, we can do it in our next life, so we can wait for a long, long time!” Flexibility and patience can be good negotiation tools.

Interestingly, when Dr Godbole, joint secretary, was on a trip to a conference at Washington, I was in conversation with him and constantly kept referring to him as sir, much to the amusement of my counterpart in World Bank. She asked me, “Why do you keep using ‘sir’? I call the vice president Ernie Stern, Ernie. So why should you call anyone ‘sir’?” I replied: “It’s simple because I can also say, ‘No, sir’, while you may, to keep the job, have to say ‘Yes, Ernie’. That’s the only difference!”

***

In August 1983, Andhra Pradesh CM, NT Rama Rao, invited me back to the state. As per rules, I was to go back to India around the same time. There were some who had quit the government and stayed behind. I, too, had opportunities but felt that, in the US, I would ‘exist’ in luxury while in India I could ‘live’ in comfort.

I was secretary of planning, and mostly reported directly to NTR as he had kept the planning portfolio. Though NTR was hardworking, had a vision and the good of the state in his heart, he always sought external validation of his image. During one such interaction, seated in his office in his signature saffron kurta and dhoti, NTR asked me, “Am I not a great man?” “Why, sir?” I asked. He replied, “I was a very successful actor and a hero in many films. I was making crores of rupees. I sacrificed everything and joined public life, only to serve the people. Have I not sacrificed a lot?” I replied, “Sir, several people had sacrificed everything for the country during the independence struggle.” He continued: “But I started a party on my own. In a year, I built a party and captured power. Is there a precedent in history?” There was no denying that, NTR had started the Telugu Desam Party (TDP) on the Telugu pride plank, as he felt that the Centre was disrespectful to the state, and had created a strong alternative to the autocratic regime of Indira Gandhi. “The Centre has been trying to destroy me. It has been using the income tax department to harass me. They are influencing the courts, even the courts, to give me trouble! Yet, I am surviving. I am the chief minister and the people love me. Am I not a great man?” At this stage, I relented, “Sir, now I am convinced that you are a great man!”

Once, at the meeting of the National Development Council (NDC) on July 12, 1984, all the state CMs and the PM were to be present. As the planning secretary, I was to draft the speech to be delivered by the CM. Rao Sahib, the cabinet secretary, called and asked me whether this was the authentic copy of the speech to be delivered later in the day. I was surprised; such an inquiry was highly unusual. I had seen NTR rehearsing the speech early that morning and confirmed that this was, indeed, the speech. As the meeting began, when it was NTR’s turn to speak, he pulled out a folded paper, whereas the speech that I had so carefully drafted, focusing on planning and economic considerations, lay unopened. Instead, NTR, reading from the paper, launched into a political tirade against the Centre, protesting the dismissal of the Farooq Abdullah government in J&K and attacked the government for its high-handedness and manipulation. Chairperson Indira Gandhi interrupted him by saying that the NDC was not a political forum. But under pressure from three other chief ministers — Jyoti Basu (West Bengal), Ramakrishna Hegde (Karnataka) and Nripen Chakraborty (Tripura) — he was allowed to complete the statement.

At the end of the speech, NTR announced that he was walking out, prompting the other three CMs to follow suit. As he walked out, he signalled that we stay seated. After a while, an announcement was made that officials of states whose CMs had walked out were to withdraw from the meeting. As it turned out, the decision to walk out was taken the night before, but was kept a secret. NTR was apprehensive that, if word went out, the dramatic effect of making the first speech and disrupting the meeting at the start would have been lost. With this, I wondered whether NTR distrusted me as a person, a professional civil servant or an intellectual. Maybe, he felt that being in the IAS, I would be more loyal to the Centre.

Incidentally, many of NTR’s policies were often opposed by some MPs and MLAs. Once, at a meeting of a dozen legislators in NTR’s room, they expressed their concerns by stating that they, too, were democratically elected representatives and wanted to have more say in the functioning of the government. NTR waxed in eloquent terms the importance of democratic values and assured them of addressing their concerns. As soon as they walked to the door, NTR looked towards me and said in a voice loud enough for the departing legislators to hear, “Reddy garu, do you see those fellows? They won by parading my photograph on the streets. If you put one rupee on their heads and auction them in the bazaar, they will be sold for half a rupee. And they say they represent the people! Those are the fellows who are trying to teach me how to run the government.” The hapless politicians could do nothing but continue on their way out!

But my days with NTR came to an end with his defeat. This was also the time when I opted to move back to the Centre.

***

It was sometime in 1990 that I began my stint, dealing with the balance of payments crisis, as it unfolded. The period was a politically tumultuous one, following the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi, coming on the back of the fall of the Chandrasekhar government and a caretaker government running the show, till Narasimha Rao took over.

At one stage, there was a suggestion to freeze non-resident Indian deposits with banks in India. When asked for my view, I suggested that such an option should not even be brought up in any discussion or documented. My concern was that if India lost the confidence of her diaspora, it would hurt our self-respect and pride across the globe.

At one stage, I was told that I might have to travel to Brunei one night secretly to obtain funds under instructions from the finance minister! It was a mission that I had to keep privy even from my family. I had packed my suitcase and told my wife Geetha that I was going to Mumbai for some urgent work. It was unwise and impractical and, fortunately, a little before midnight, the plan was called off.

There was a strong consensus among political leaders and professional circles that the country should not default on its debt obligations. The pledging of gold to the IMF was possible because of that consensus. In the three years of 1990-93, which spanned crisis and reform, we had seen three prime ministers, three governors, three financial secretaries and three chief economic advisors, I was the only constant. What was needed was political sagacity because everyone knew that, over the past 10 years, India’s old economic model had broken down. What was lacking was the political will and wisdom; the crisis was also an opportunity. PV Narasimha Rao had it, and the country was also fortunate that Dr Manmohan Singh had become the finance minister as he had been closely involved with the policies of the past – the good, the bad and the ugly.

Once the BoP crisis blew over, and after India embraced liberalisation, I offered prayers at the Balaji temple at Tirupati. Kulkarni, my colleague at the RBI, got his head tonsured as a traditional token of gratitude! It was only appropriate given that, outside of any central bank vault, Sri Venkateswara Swamy held the largest stock of gold at 200 tonne!

***

In May 1993, I was promoted to the rank of additional secretary in commerce ministry. During my stint at the ministry, I spent a lot of time understanding the Indian economy, even more than the chief economic advisor! But my interactions with the commerce minister increased after P Chidambaram took over. Clad in a traditional South Indian snow-white dhoti and shirt, Chidambaram had the reputation of being a brilliant man and unsparing. A master of detail, he was also an unforgiving boss. Once he found a mistake in the file that I had submitted. “It’s a mistake,” he remarked. “Yes, sir. It is a mistake,” I replied. He looked at me and repeated: “It’s a mistake.” “Yes, sir, it is a mistake.” He repeated, “It is a mistake.” I submitted. “I’m sorry, sir. It was, indeed, a mistake.”

I had another interaction with Chidambaram, which went differently. He had sought my views, we differed and, after hearing me out, it was clear that his stance was wrong. “It was a mistake,” he exclaimed. “It was a mistake, sir, a mistake,” I repeated. He looked at me with a smile and said, “Yes, it was. I am sorry.” The ice was broken.

In August 1995, I was posted as secretary, department of banking, in the ministry of finance. I was happy to be back. A year later, one day in July, I got a call from Surendra Singh, cabinet secretary, asking me to meet him at his office in Rashtrapati Bhavan. He said, “Venu, you are senior and you have many years of service left. So, we are thinking of posting you to an important ministry I have in mind — ministry of defence. I just wanted to tell you this personally.” I responded, “Sir, please do not bother. I will quit.” Though an important posting, I felt defence was not my area of expertise.

Around the same time, SS Tarapore, RBI deputy governor, who was about to retire, told me to consider his job at the central bank. Incidentally, during my days at the commerce ministry, RBI governor C Rangarajan had suggested that I join the RBI but I hadn’t shown any interest. But this time when he suggested my name, Chidambaram asked me if I was interested and I said “yes”. That was a turning point which enabled me to learn applied economics under the guidance of Rangarajan.

***

I was sad to leave the government that I had served for three decades, but during my tenure of six years, from 1996 to 2002, I had greater freedom to state my views on broader policy matters than when I was in the government.

Among many challenging and fulfilling moments as deputy governor, one is related to the RBI’s balance sheet. A bone of contention had emerged over what amount should go to the reserves before transferring surpluses to the government. In 1995, the central bank’s auditor had suggested that transfers to the reserve must have a relation to the total size of the balance sheet, and also the profits for the year. An informal group was set up in 1996-97 to look into the issue. The group recommended that indicative target of 12% of the size of the bank’s assets would be appropriate, while the prevailing level was much below that. Finance secretary Montek Singh Ahluwalia sought my opinion by asking me: “This is too complicated. If you were in my position in the finance ministry, would you agree to the proposal?” I replied, “Yes, definitely.” He gave me the go-ahead. Such was the mutual trust and level of respect for professionalism that we had in each other.

Another interesting episode was around the depreciation of the rupee. I felt it should be allowed freely as long as there was no serious panic and, in the meanwhile, the central bank had to be ready for an initial marginal overshooting over the desired level. Rangarajan, Ahluwalia, Shankar Acharya and I went to meet Chidambaram, who was then the finance minister, at his residence to debate on this. Chidambaram felt that the RBI had to moderate the pace of depreciation, but I was against it. The governor and finance secretary left it to me to argue my case, against intervention at this stage. But I couldn’t convince the minister. Despite the minor differences, the overall coordinated strategy in the forex market was successfull. The subsequent Asian financial crisis, however, underscored the fact that a timely induced exchange rate depreciation had helped in moderating the impact of the crisis. Tarapore, my predecessor in RBI, in fact went on to write in the magazine of the Bank for International Settlements that, when definitive monetary history of the period would be written, “Dr Reddy would come out as the saviour of the Indian exchange rate policy.”

In November 1997, Bimal Jalan took over as the governor. An informal, affectionate, pleasing and cheerful personality, Jalan was essentially a strategist, with a quick and instinctive grasp of complex realities, while Rangarajan had a deep understanding of systems and liked to drive the changes.

Jalan was instrumental in ushering the indirect intervention of the RBI in the forex market through select banks, a step which, initially, I felt wasn’t right. However, later, the efficacy of the move did prove that my apprehensions were wrong. There were instances that we had strong, differing views, but mutual trust never diminished.

Once, during AB Vajpayee’s tenure, following the Pokhran nuclear test, Jalan had been alerted that the US would be imposing sanctions on India. Jalan was worried that the move would create a turmoil in the forex market and wanted to issue a statement of assurance. I said, “Sir, my only request is that no statement be made till we observe the reactions.” The idea was not to stick our neck out given that there were too many imponderables and uncertainties.

As we were leaving, I accompanied him for a final word, when he told his executive assistant: “Sandip, no statement need be issued.” He looked at me with his usual disarming smile and said “Okay, good night, Venu.” The next morning he rang me up and said: “Venu, congratulate me for accepting your advice! We did not issue any statement, and the markets are reasonably normal.”

Another memorable interaction with Jalan was with regards to the exposure of banks to equity markets. There was a proposal to increase the exposure of banks to equities, from 5% of incremental deposits to 5% of total outstanding advances.

My view was that linking exposure to 5% of advances would result in a sudden and huge window of exposure to equity in one go, and that could be exploited were a bank to collude with a broker. My fears weren’t misplaced.

On March 1, 2001, when the Ketan Parekh scam roiled the markets, Jalan called me to his office. He said, “Actually, there has been very little increase in aggregate exposure of banks to equity markets, still this scam took place. Tell me, how did you and why did you suspect that something like this might happen?”

I replied: “Whenever I assess a policy proposal, I think of only one thing. How could the player in the finance business make money? If I am on the other side, I can think of making money out of every change in policy. That would be the market’s reaction. So, I keep asking, what would that attitude of markets mean to my policy?” A smiling Jalan said: “I am glad that you are not on the other side.”

***

My extended term at the RBI came to a premature close when I was offered the executive director’s position at the IMF. “Venu, why were you in such a hurry to say ‘yes’? Do you know how they select an executive director in the government? Either for services rendered to those in power or to get rid of you. You did not serve anybody’s interest,” Jalan questioned me. I told him my son, daughter and grandson were all in the US and I was more than happy to go.

So, I took charge as ED at the IMF in August 2002. But the stint didn’t last for long. In April 2003, I was in India and made a customary call on Jaswant Singh. Out of the blue, he said: “We are considering your candidature for the RBI governor’s position.” I replied: “Sir, I have a three-year term… I am happy and settled in the fund. I am already 62 and not keen to be considered.”

But that was not to be. Though my family back in the US wanted me to be firm about not moving out of the fund, I knew I could not afford to displease the government beyond a point. More importantly, I would not be able to work at the IMF after defying the government!

So when I took over as the RBI governor, I called upon Manmohan Singh, who was then in the opposition. He was very happy and said: “I can sleep peacefully as the financial sector is in your hands.” Dr Singh was always very generous to me.

***

As the governor, it was quite an interesting journey. The RBI became much more outward-looking and market-friendly rather than an inward-looking regulator. But it was also a time for guarding the RBI’s autonomy even while working closely with the government.

During Jaswant Singh’s tenure as the finance minister, there was excess capital flows, and so the RBI had to use the money for sterilisation. I was of the view that the government had to take the responsibility through cost of the sterilisation of bonds, but the finance ministry’s view was that, were the fisc to bear the burden, the RBI would be seen as losing its independence. My stance was: “Dealing with capital flows requires support from the government, and not independence.” I still remember the sentence I told the finance minister: “Sir, a strong central bank can serve you better in times of difficulties.” Being a statesman, Dr Singh supported the RBI, despite adverse impact on the general budget.

Soon after the UPA came to power, the government wanted to implement a policy of opening up our private sector banks to foreign banks, which was announced by the NDA in consultation with my predecessor Jalan. I, though, had opposed the implementation.

At one stage, Chidambaram asked: “Just because the RBI governor changes, should the commitment of the government to the global community be changed?” He was right, so I quietly told the secretary in finance ministry that my conscience won’t allow me to be party to this. I believed that we could allow for the change in a time-bound fashion, but if the government is not prepared to reconsider its decision, I offered to get admitted into a hospital and retire! The government could then get a governor committed to the policy, rather than a reluctant one like me.

To the credit of the leadership, the matter was reconsidered. The finance minister told me: “We cannot change our policy, but we accept your point that it’s premature, so give me a roadmap.” I, too, agreed, because my point was not to prevent the move, but it was more to give an opportunity for the domestic banking industry to develop, deregulate and then open up for competition.

I believe that, in policy-making, arriving at an appropriate solution is both science and an art — in search for the desirable, move towards the feasible, but at the same time assess the cost and benefits of both. It’s always important to keep the desirable in view, while doing what is feasible.

***

Today when I look at my career, I believe all, be it ministers or bureaucrats, have been, by and large, good. They rarely approached me for anything that I wouldn’t have accommodated. Of course, my family, relatives, my wife, all of them took care not to do anything that would compromise my integrity. So, I would say, if I have been reasonably successful in my career, I owe it as much to my parents, my family, my relatives and my friends. I still remember my ayya’s words that character is most important, and that fate decides your life.

If ever there ever was a quote to summarise my journey in life it would be this:

Haste not—rest not—calmly wait,

Meekly bear the storms of fate;

Duty be thy polar guide,

Do the right whate’er betide;

Haste not—rest not—conflicts past,

Peace shall crown thy work at last.