In June 2011, Ashok Chokalingam, who handles international operations at Amrut (‘nectar of the gods’ in Sanskrit) Distilleries, got a call from Harrods. London’s iconic retail store wanted to stock Amrut’s single malt in its ‘whiskies around the world’ section. More than 23 different whiskies from countries like the US, Japan, Australia and Canada were chosen. Amrut was the only Indian single malt to be featured on the list. It went on sale at Harrods in October 2011 and remains, to date, the only Indian liquor brand to ever retail at the store.

It’s been a spirited journey for Amrut, starting from a debut in an Indian restaurant in 2004. Whisky guru Jim Murray rated it at 82 on a scale of 1-100 for the first time in 2005. It was under the spotlight again when Murray declared Amrut Fusion single malt the world’s third-best whisky in the 2010 edition of his Whisky Bible. In the whisky pecking order, single malts are produced by a single distillery in a single batch using only malted barley. Blended whiskies such as Johnny Walker, Chivas Regal and Seagram Seven are made by mixing 30-40 different single malts along with other grain (corn, rye, wheat) whiskies. Typically, the search for a good whisky pretty much starts and ends in Scotland.

Not even Indians, among the biggest consumers of whiskies in the world, consider Indian whiskies good enough. It’s only natural that the rest of the world didn’t think much of them either. So when an Indian brand, that too a single malt, was judged to be better than some of the Scottish brands that have been around for decades, the world had to sit up and take notice. The fascinating journey of a small IMFL (Indian-made foreign liquor) distillery outside Bangalore, which was struggling to sell single malts in Europe till a few years ago, appears to have come full circle. And it all began accidentally.

Heady start

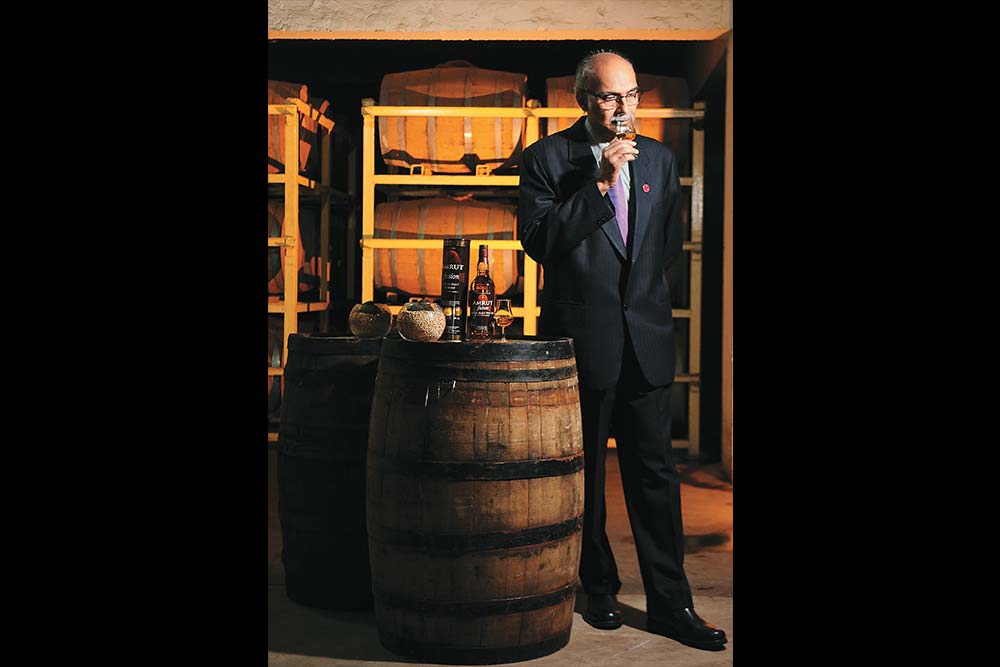

“We knew we were doing it right,” says Neelakanta Rao Jagdale, managing director, Amrut Distilleries. “But did we intend to produce malt whisky in the beginning? No, that was more by chance.”

Amrut, which was founded in 1948 by Jagdale’s father JN Radhakrishna, launched its first brand, Silver Cup brandy in Karnataka, 1949. It started supplying liquor to army canteens in 1962. In fact, it continues to supply some of its brands in the domestic market — Amrut XXX rum and Prestige whisky — to the army. Then, in the 1980s, while his peers were converting molasses to alcohol, Jagdale wanted to create a premium whisky blended with malt.

Experts will tell you that you only need three ingredients to make a single malt whisky anywhere in the world — barley, water and yeast. The complex starches in barley are converted to simple sugars in a process called malting; yeast ferments them into alcohol; water is separated out via distillation; the spirit ages in oak casks for at least three years before being bottled. For the next decade, Amrut spent perfecting the art of making a good malt whisky.

Earlier, Amrut aged malt whisky for a year or so before blending it. As customer preferences changed and less malt whisky found its way into blended variants, by 1995 Amrut had surplus stock of malt whisky. Jagdale decided to allow some barrels to age longer and see how they would turn out. By 2000, the whiskies had been ageing for almost four to five years and soon some unexpected revelations followed.

Alcohol matures faster in India than in Europe and the US because of the heat. The loss due to evaporation, called the angel’s share, is higher — 11-12% a year compared to the 2% loss in Scotland. But, “the taste profiles were much better, almost matching some of the 12-year-old whiskies,” says Jagdale. “To enter the European market, you needed to have whiskies that were aged for a minimum of three years, which we had. So we decided to try our luck in Europe. We thought if we have to pass the exam, let us go to the toughest school.”

The company’s foray into the European market was spearheaded by Neelakanta’s son, Rakshit Jagdale, now executive director. Back in 2001, while studying for his MBA in England, he set out to see if there was a market for single malts made in India. “Since Indian beers like Kingfisher and Cobra were popular, we wanted to see if we could find a niche for Indian whisky,” he says. Rakshit distributed samples across 250 restaurants in the UK and Scotland, getting positive reviews along the way. The turning point came a year later, when Pot Still, a famous whisky bar in Glasgow, served the Amrut single malt during a blind tasting one evening. When asked to identify the region and age of the whisky, most drinkers said it had to be a 12-15-year-old malt from Scotland or Ireland. “Most of customers were shocked to find out that it came from India,” says Rakshit. “We knew that we had a winner on our hands.”

Nursing their drink

After the bottling and packaging issues were out of the way, Amrut launched its single malt in Café India, a restaurant in Glasgow, in August 2004. But it was one thing to impress whisky drinkers, quite another to convince hard-nosed European distributors that a good single malt can come out of India. “After our launch in 2004, the first few years were difficult,” says Neelakanta Rao. “We found it hard to convince European buyers to try our product. In fact, we started to evaluate whether it was worthwhile pursuing our overseas foray at all. I decided to it give one last shot, thinking we would be a few crores poorer if we failed but, if we succeeded, we would put India on the whisky world map.”

Amrut changed its distribution strategy, moving away from restaurants to participate in tasting events and shifted to premium whisky bars and retailers. The company currently sells through a single distributor in each of the countries where it retails. Back home, the company continued to improve the quality with the help of renowned Scottish consultancy Tatlock and Thomson, experts in analysing alcoholic drinks. Then Jim Murray happened.

Amrut is now present in 21 countries, including the US, Canada, France, Sweden and Japan. Amrut Fusion is priced at £34 in the UK and ₹2,210 in India. Its equivalent is a 10-year single malt called Talisker, which retails at £38 in the UK and ₹3,800 in India. The product portfolio has been expanded to 9-10 variants, including some limited editions, which have been received well by customers.

“An important part of their success is the fact that they have spent a lot of time developing the product,” says Vikram Achanta, CEO of Tulleeho, a firm that provides consultancy services for the beverages industry. “It’s good they are not complacent with their success and are coming up with newer variants to keep whisky connoisseurs constantly interested in their product.” On the cards now is a premium rum for the overseas market by 2013.

Cheers!

Amrut expects to sell around 15,000 cases of malts in FY13, against the 10,000 it will do in FY12. By 2015, Amrut hopes to export 20,000 cases worldwide. “There is demand but we are not able to service it,” says Neelakanta Jagdale, who wants his company to remain an Indian brand and does not plan on changing to a more Scot-sounding name. “We cannot accelerate the maturation process beyond a point. A good whisky can never be a mass product.”

Distillers typically make the bulk of their revenues from blends and Amrut is no different — its single malts account for barely 5% of the ₹185-crore turnover while good ol’ Silver Oak brandy, Old Port rum and Prestige whisky bring in the revenues.

Ironically, the single malt debuted in India only in 2010 because most of it is shipped overseas to meet the increasing demand in foreign markets. Amrut currently retails its single malt only in Karnataka, where it sells about 600-700 cases annually. Delhi and Mumbai may come up next year but the company says the high entry costs and complex excise laws in different states are a deterrent to further expansion in India.

Being the only Indian single malt in the overseas market is another definite advantage. “Building a liquor brand is tough because there is not much in terms of product differentiation,” says Abhijit Avasthi, national creative director, Ogilvy & Mather. “How you segment the market and how innovatively you get the message across, is critical. It’s very important that the brand has a unique proposition,” says Avasthi. “For Amrut, the Indian name works because it arouses curiosity.” The strategy to take it to Scotland for approval was the smartest move. “It’s as good as getting a car approved by the engineers in Italy,” says Prathap Suthan, chief creative officer, iYogi. What more do you need?