Playing with fire seems to be no big deal to the two young women in a brightly lit room. The detonating cord sifts its way through their hands as if it were a piece of paper. Observing the slightly terrified look on our faces, they break into a smile and casually say in Hindi, “Yeh to roz ka kaam hai” (this is a part of our daily routine).

No more than in their mid-20s, these two are part of a workforce of 2,500 who are involved in the manufacture of slurry explosives, cartridges, cast boosters and detonating cords. There is no doubt that it is a tough job and not made any easier in the sweltering heat of central India. We are in Chakdoh, 40 km away from Nagpur and an hour by car. Across 750 acres, on which Solar Industries India’s manufacturing plant sits, the smell of chemicals (ammonium nitrate and calcium nitrate, we are told) is mildly astringent. This is one of the 25 plants that Solar owns.

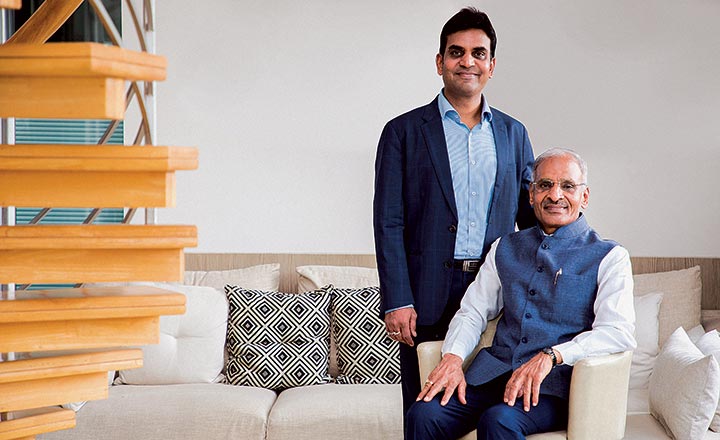

The company’s 66-year-old spirited chairman, Satyanarayan Nuwal, named the company as a tribute to the star. “I have been fascinated by the sun, even as a boy,” he says. The business he founded in 1984 as an industrial explosives trader expanded into manufacturing in the ’90s; and scaled up, headed to overseas markets even setting up manufacturing units there and went public in the 2000s. Today, it is the leader in the domestic industrial explosives market with a dominant 25% share, a sizable lead over the second-largest player with 12%. Revenues have compounded at 12.74% over the past five years to Rs.24.62 billion as of FY19.

The turning point was when the founder realised that he needed to de-risk the business, which till FY07 had over 70% of revenue coming from the state-owned Coal India (CIL). Solar deftly shifted focus to other verticals besides investing in a new one. “It was critical for us to de-risk but the strategy has paid off,” says the promoter’s son Manish Nuwal, who is also the MD. In FY19, revenue from CIL was down to 17%. Instead, exports and overseas business is now the primary earner with a revenue share of 35% (See: The foreign hand). Barring the dip in the fourth quarter of FY19, owing to short-term troubles in the customer market, exports have been doing well for the past few years.

But what’s really changing Solar’s fortunes is the business it has been engaged in over the past two years — housing & infrastructure (mostly domestic road construction) generates 27% of sales, and defence, chipping in with 7%. Nothing today excites the folks at Solar more than the potential of these two businesses.

Gunpowder all the way

Sitting in his large room at Solar’s corporate office in Nagpur, the senior Nuwal recalls the company’s foray into defence in mid-2009. Attired simply and devoid of footwear, as is the norm in the office, the lanky man saw a clear potential. “We were in the business of explosives anyway. The only ammunition manufacturer in India was the ordinance factory and anything needed beyond that was imported,” he says.

At that point, the private sector in defence was barely welcome, though Satyanarayan was convinced that this would soon change. The management may have been desperate for a break. Solar had recently gone public, in 2006, and its dependence on CIL had begun to worry investors. There was the housing and infra vertical, primarily driven by highway construction, but it was struggling to achieve scale. The company began expanding its domestic operations, besides expanding into exports markets and even set up manufacturing units in Zambia, Nigeria and Turkey.

Defence was seen as the next frontier. Solar was looking to manufacture ammunition in addition to military explosives and propellants for rockets, pyros, bombs and warheads. They wanted to provide the feed into defence equipment while other larger private sector players such as Mahindra, Larsen & Toubro and Tatas manufacture and supply the hardware. Satyanarayan’s patience was sorely tested though.

Just getting the licence took two to three years, with no clarity on when revenue would kick in. “Setting up the infrastructure and getting the transfer of technology took another five years. Passion and patience were required in equal proportion,” says Satyanarayan. To date, a capex of Rs.4.5 billion has gone into the defence project with a plant set up in Sawanga, a short drive from Chakdoh.

In 2014, the defence sector began showing the promise Satyanarayan had predicted. The new government was allowing a larger FDI in the sector, incentivising use of Indian talent and product, and welcoming private players to bid for mega manufacturing deals. The wave had arrived and Solar headed out to crest it.

Over the past two years, the decision to go after defence appears to have paid off. The business raked in Rs.1.70 billion in FY19, compared with Rs.370 million for the previous fiscal, a near five-fold jump (See: On the offensive). Satyanarayan expects the business, which had an order-book of Rs.3.96 billion as of FY19, to hit Rs.3 billion in the current fiscal. In January 2018, it was awarded the transfer of technology for mass production of a solid propellant booster for the world’s fastest supersonic cruise missile, BrahMos. When private players were first invited to make ammunition for the Indian Army, Solar sent request for proposal for three kinds of ammunition. This is still at the RFP stage.

He hopes to be compensated for the long gestation period. If explosives gave him an operating margin of around 20%, defence would have to be at least 5% more.

Vinit Bolinjkar, head of research at Ventura Securities, believes that procuring any kind of defence equipment is a one-time capex for the government. “The difference with ammunition is that it is a defence consumable with a perennial order flow,” he says. “Basically, you become the preferred partner for specialised work — that could well be the case on ammunition for rockets or something as sensitive as that. Effectively, Solar will have the advantage of ‘competitive immunity’ for eight to 10 years, which will steadily increase business and margins. The challenge is that orders could be lumpy — meaning payment could be staggered, which could have an impact on working capital.”

This challenge could also keep out newbies, while Solar has a clear headstart. At present, there are two major players, Solar and Premier Explosives. A third player is Gulf Oil. New players will also face clearances as a serious entry barrier. Satyanarayan himself maintains that anyone looking to get in today will need to set aside seven to eight years before business of any consequence takes place.

Infrastructure it is

While defence is the promising new vertical for Solar, explosives remains the primary business. The demand here largely comes from road construction, with housing also picking up pace. The company groups the two together under the housing and infrastructure segment. “In FY19, though demand from the mining sector was subdued, we saw strong demand from the infrastructure segment, particularly road construction,” says Manish. Concurring with his view, Solar’s CFO, Nilesh Panpaliya adds, “Any growing economy, where infrastructure creation is underway, will need explosives and that is a big play for us.” In the past fiscal, explosives needed for roads and housing brought in revenues of Rs.6.63 billion, an increase of 36%, making it the second-fastest growing segment after defence, though on a much smaller base. According to him, 70% of the growth came from road construction with the rest from housing. This year, they are expecting housing to take off too.

The ecosystem in road construction has evolved, serving Solar well. Earlier there were many contractors or sub-contractors that the company had to negotiate with, but now the government issues fewer licences to deal in explosives. Therefore, there is greater transparency and ease of doing business. “With ammonium nitrate having been brought under the licence regime, apart from approvals required at district, state all the way to the home ministry, it has become very difficult for a new entrant (or sub-contractors),” he says.

The previous two fiscals also saw increased activity around road construction after land acquisition was made easier through The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement (Amendment) Bill passed in 2015. The change of pace — to 27.5 km of road per day from 12 km per day in 2014-15 — is reflected in Solar’s revenues. The government’s announcement during the FY18 Budget to spend Rs.5.97 trillion on infrastructure, or a hike of Rs.1 trillion, has been music to the Solar management. The allocation for both railways and road construction has been increased.

In housing, Manish is hopeful about the prospects from the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana, which targets building 20 million houses in urban India and another 30 million in rural India by 2022. Panpaliya is certain that revenue from roads and housing can easily rise by 20% each year, going by the existing pace of activity.

But what has everyone’s heart racing at Solar is the interlinking of rivers project. Though it is currently at a stage of infancy, it is also the need of the hour in the backdrop of a water crisis. Manish believes that if it takes off, water will have to be diverted through waterways, which will translate into a significant demand for packaged explosives. “We will need to build canals and that requires land evacuation, and then there will be the requirement for cement and steel,” he says.

This project is very likely to happen if we go by what Vishwas Jain, managing director at the well-known Consulting Engineers Group has to say. The limited availability of water will be the biggest threat in producing 500 million metric tonne of food grains by 2050. “Now, rivers will be linked by a network of reservoirs and canals to deal with both drought and floods. That will not just decrease the farmers’ dependence on uncertain monsoons but also bring in millions of hectares of cultivable land under irrigation,” he explains.

Ventura Securities’ Bolinjkar, too, is optimistic: “We estimate the project to be several times larger than city gas distribution. This will be across the country and can be an additional revenue stream for Solar.” He adds, “It may not necessarily be a long-term game. One change in policy during the Budget could dramatically alter the fortunes for a company in the business.”

The government has already announced that this will have an outlay of Rs.5.5 trillion and the construction of 30 canals and 3,000 small and large reservoirs. It looks good but Jain says that companies have to be prepared for a gestation period of nothing less than a decade. “Water is a state subject and how much each state will be willing to compromise could be a tricky issue. Environmental concerns too linger,” he says.

Heart of coal

Much as the dependence on CIL has reduced, Panpaliya makes it clear that the government undertaking will continue to be a big part of Solar’s story and would want the PSU to be its largest customer. Not surprising, since it helps Solar remain the largest consumer of ammonium nitrate, enabling the company to get very competitive prices from the supplier.

The concern on margins tapering off in bulk explosives does not deter him one bit. “While CIL ensures huge volumes in the explosives business, margins will have to come from our other businesses,” he states categorically.

Bolinjkar agrees that CIL will continue to remain critical since it is a stable revenue stream, though it is a high volume, low margin business. There are other benefits. In the case of contracts with Coal India, Solar has to deal with just one customer (the government) and not several contractors. “The time required to do the business is not much since they have been doing it for years, and CIL’s business aids operating profit growth quietly,” he adds.

Bolinjkar believes the company is rightly built to make the best of government-generated businesses. “What is not adequately appreciated is how they deal with regulation,” he says.

At a time when businesses are wary of dealing with the government or being dependent on the lumbering machinery for their revenue, Solar is only too happy to be in this space. “We are in the game, if the government promotes a sector,” says Manish with a smile.”