November, 12, 2004. The balmy Friday morning was a dream come true for 35 Wharton students. They had a lunch date with the world’s greatest investor. Warren Buffett hadn’t extended his customary invitation to the B-school for the past few years, which meant there was a mad scramble in the Investment Management Club for the limited spots. Akhil Dhawan was among the few who got lucky that day. “People have paid upward of $2 million to have lunch with Mr Buffett so, the way I see it, I recovered a large chunk of my Wharton tuition in one day — both monetarily and intellectually,” he says.

Dhawan’s introduction into the world of investing wasn’t through Buffett, though. It was through his brother Ashish, who founded ChrysCapital, one of the earliest and the finest private equity firm in the country. After his schooling in India, Dhawan went to Cornell University in 1994 for an undergraduate degree. A turning point that would shape up his investment thinking in the years to come, happened by sheer accident. “One of my roommates in college had bought Robert Hagstrom’s The Warren Buffett Way. I picked it off our bookshelf for a casual read and my fascination for Buffett started right then.”

Around the same time, Ashish Dhawan — an MBA student at Harvard — was interning at Goldman Sachs’ proprietary investment group and the firm had given him The Intelligent Investor to read. “I wasn’t getting paid that summer, so I was sleeping on my brother’s couch. He recommended the book,” says Dhawan. “I had never bought a stock, but Graham’s distinction between investment and speculation stuck with me.”

Dhawan’s first job was also with the most sought-after investment bank in the US — Goldman Sachs — as an analyst in the corporate finance division. Those years (1998-99) were boom times in the US and Dhawan got to work on several deals, especially stake sales to private equity (PE) firms. The dotcom craze had started and smitten by the same, Dhawan came back to India to set up a company of his own. As events proved, India wasn’t quite ready for the tech revolution and Dhawan returned to the US in under a year. And this time, he moved to the other side of the table, joining SG Capital, a mid-sized PE firm with a corpus of $500 million. Since the US markets are relatively mature, PE tends to be a little value-oriented with greater attention to the multiple paid and so on. “That gave me the taste of investing and also insights into how businesses are run. The distinction between overpaying for an asset and getting it cheap became quite clear over those years.”

The flip side of being in a mature market was way too much competition; almost all deals had intermediaries and would go through an auction. “It was a question of saying who, not necessarily is a fool, but has the lowest cost of capital and the greatest appetite for lowest return.” That wasn’t too exciting, so Dhawan quit to joint Michael Karsch’s hedge fund, Karsch Capital, for a brief while before heading to Wharton in 2003.

“What I loved most about Wharton was the opportunity to interact with many ‘investing greats’ in an environment where their guard was down,” says Dhawan. Listening to people such as Seth Klarman (he stressed the importance of really thinking through downside risk while investing), Julian Robertson (he said he enjoyed pitting a bullish analyst against a bearish one, and listening to them argue — it gave him clarity) and Glenn Greenberg (he talked about how he liked to buy businesses that were cheap and that had no competition, which took a lot of risk out of the investment) offered invaluable lessons, says Dhawan. “I took a class on distressed debt investing where Howard Marks came and spoke to us — a lot of what he said is in his letters to investors, and is timeless.”

India beckons

Primed with immense curiosity and admiration for the most accomplished disciple of Benjamin Graham, Dhawan and his batchmates waited eagerly for Buffett to reach his office at Omaha’s Kiewit Plaza at 9.30 am. Buffett arrived, dressed in his usual, nondescript way — dark suit, white shirt and discreetly printed tie — and brimming with his usual quota of energy and wit. For the next three hours, he answered the students’ questions, ranging from his habits and hobbies to investing wisdom. One piece of advice stood out: “Don’t work for anyone whose investment philosophy you don’t agree with.” It was too much to absorb in one day — Dhawan came to grips with a lot of what Buffett said, only later.

MBA over, Dhawan returned to Karsch Capital to cover the US and Asia, including India. During his internship with Karsch earlier, Dhawan had his first brush with Indian markets interacting with about 40 companies. Unfortunately, the fund posed two constraints — the lock-up on capital was not long enough and because the fund size was about $3 billion, his addressable universe was only the top 100 companies, since he needed to deploy around $125 million in each business and also stay liquid.

Summer 2006 — by when Dhawan had been with Karsch Capital for a year — was a trial by fire. The market fell suddenly and some of his mid-cap positions took a severe beating. The fund had to fire-sell the stocks as it could not afford the volatility. “Being a long-short hedge fund, the fund was sold to investors as a low volatility product, rather than as a high return product plus it had a 90-day lock-in. That was counter-intuitive to my thinking. Also, mid-caps is where the real value lies in India. If you couldn’t invest in them, it would be a lot harder to find good bargains.” A year later, Dhawan decided to leave the firm and come back to India to set up his own fund. Locus — a mathematical term for a collection of points that mean something when put together — came into existence in 2007. “Buffett’s advice on how to choose your firm was not the reason I chose to work with SG Capital, but it was the reason I quit,” says Dhawan.

Still, 2007 wasn’t the best time to start a fund — it was a frothy market. Accordingly, Dhawan went very slow on deploying cash. “By the summer of 2008, we thought we were done and there was a classic sell-off in India. The index was already at 12 times earnings. So it didn’t look bad.” By the second or third quarter of 2008, Dhawan was heavily deployed. Then came Lehman, the big fall, and investor panic. Dhawan decided to take some loss to get liquidity and preserve capital. “We recognised that being in India in the mid-cap space, we were in an asset class that was literally on the fringe. If you were in a world where banks worried about lending to each other, nobody is going to care about mid-caps.” Dhawan sold heavily — nearly 40% of the investments — in September and October 2008 and waited in cash.

“We changed track a little bit. We said our goal is to find value. At that time, there were many companies in India available at phenomenally cheap prices. We recycled all of that capital into high-quality stocks such as Infosys and HDFC. We bought top-quality companies at 10 times earnings, saying if anything is going to hold value, these will.” By March, when it became clear that the markets had thawed and things were returning to normal, Dhawan sold off the large cap portfolio and redeployed all that capital back into quality mid-caps.

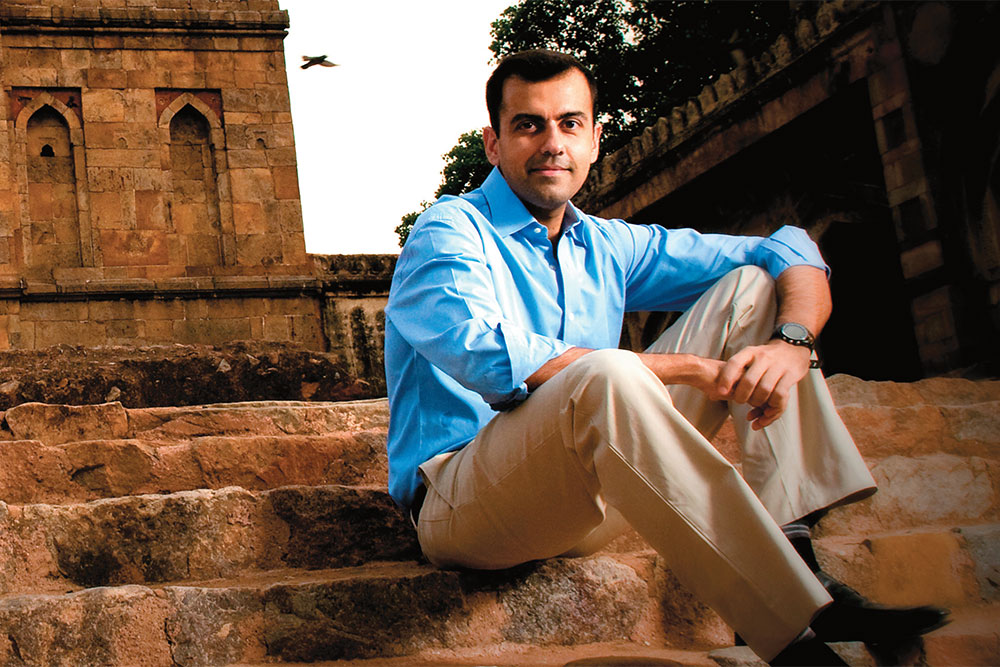

Now, sitting in his spartan office at Sundar Nagar, an upscale, old money neighbourhood in Delhi, Dhawan shakes his head thinking back to that time of uncertainty. Investing — especially value investing — is a lonely business. “Buying stocks on my own from 1998 onward, and looking back on my mistakes and successes, has been pivotal in reinforcing what value investing means to me,” he says.

The Buffett way

Buffett had seen it coming. He had anticipated the housing crisis that was at the heart of the financial meltdown of 2008, even when at the time of the Wharton grads meeting. During lunch, one of Dhawan’s classmates asked Buffett whether it was a good idea to buy a house. “That is probably the most important purchase in your life, the home you live in. These are your early years. Real estate tends to be a very long cycle business. The one place you have to have patience is real estate. I would wait five to seven years. I certainly wouldn’t buy it today,” Buffett said. He was right.

As Buffett with supreme ease batted every question thrown his way, someone asked, “We know you read every annual report in the S&P 500 — and then some — every year. What do you do when you pick up an annual report — how do you read it?” Everyone waited anxiously for Buffett to reveal his secret approach or his favourite footnote to the accounts. Sometimes the artful dodger, Buffett shot back: “Fast!” That wasn’t the only instance of Buffett’s famed wit and irreverence that day. Answering a question on the risks of derivative instruments, he quipped, “It’s like AIDS — it’s not about who you slept with, but who they slept with”, pointing out that the risks in the underlying security are someone else’s doing. Not surprisingly, Dhawan stays away from derivatives.

The first stock Dhawan bought for “keeps” was Shriram Transport. This was in end-2005 when he was at Karsch. The investment grew 50% before it shed all its gains from its high during the sell-off in 2006. The stock became almost impossible to sell.

The decision to invest was a straight lift from Buffett’s philosophy of moats, a term Buffett has immortalised in the investing world. A moat is a deep, broad ditch that surrounds a castle to provide it with a preliminary line of defence; Buffett’s moat refers to a company’s unique strengths that create a barrier for competitors. Shriram Transport had a clear moat in that it had perfected lending for second-hand commercial vehicle purchases, having built a great network of relationships with fleet owners. While the business was considered risky by competitors, Shriram created a niche that was hard to replicate.

There are several other stocks that Dhawan picked based on the same philosophy, although the most challenging part of following Buffett’s approach is identifying a moat. Dhawan’s heavy-duty picks after he started his own fund were Greenply Industries, Shriram City Union Finance, Balkrishna Industries and Bajaj Auto Finance (see: Betting on moats).

Dhawan’s strategy has been to build a concentrated portfolio of 15 or less companies that, ideally, are cheap. “There is a little bit of both Buffett and Graham in this. But we are looking for more Buffett and less Graham.” While it’s easier to find Graham-like situations by simply running stock screens, the mistake investors often make is to weed out companies by laying additional criteria like the quality of balance sheet, earnings, management, and picking up just three or four stocks from the selection. “We made that mistake and now are very wary. If you are following Graham, you should be buying 50 things and reducing your risk.

But often you end up not doing that.” Graham’s idea is to buy a basket of grossly undervalued stocks with the understanding that even if some of the stocks go bad, the overall portfolio will give very good returns because you bought them cheap. But there is a problem if you buy large quantities of these companies — if you buy into a pure Graham-esque situation and you have a concentrated portfolio of stocks bought at 50% discount, when the discount narrows to 80-90%, you are going to have a much harder time getting out because the business itself isn’t that great, explains Dhawan.

On the other hand, if you bought into a good business, which is what Buffett advises, there will always be a buyer. “Concentration works only where the business is good and you are happy holding on for a longer period of time if there aren’t enough buyers.” Dhawan currently has eight stocks in his portfolio. “Cash today is a very big bucket for us because we sold some things. Do we aspire to make that five? If we got to Mr Munger’s stature of understanding of the world, maybe,” he says candidly.

Indeed, following a Buffett or a Munger and placing concentrated bets requires you to be 100% sure about the investment. They should be good compounders and help investors sleep well at night. That also means something very fundamental: your best returns usually come from your best ideas. “Whenever we have spent time looking at something and being half there and half not there, we ended up taking a small position and it never worked.” The Buffett way is to buy a good business, with good management at a good price. And most importantly, to have the conviction to buy it in good size. Dhawan says, at one level, identifying good businesses is fairly simple — the easy ones will be consumer oriented — but the problem is that they do not meet the price criteria. “We never pay upwards of 15 times earnings. The challenge in identifying good businesses then is to look beyond the usual consumer names and find a moat. That is something we are still learning.”

Another important thing is to not begin by looking at valuations; otherwise, the price dominates the thinking. “We go into a situation saying this is a really good business and is available at an attractive price. We don’t say, this is cheap, now let’s look at the business.” While many learnings have come along the way, Dhawan also believes in sticking to his circle of competence. He looks at companies largely from consumer, financial, IT and pharma sectors. But whichever stock or sector he touches, Graham’s cardinal rule is always top of mind: margin of safety.

But even margin of safety is no guarantee to success. One of the big mistakes for Dhawan has been the sum-of-the-parts stories. “There have been plenty of disappointments here,” he says, giving the example of a real estate play where he ended up losing about 65% of the investment. It was a ₹200-crore service company that was making reasonable amount of cash in its core business, and had a lot of land, the value of which was greater than its m-cap. The management was getting phenomenal offers for that land in 2007, but it did not sell so the value never got unlocked. “Since we were focusing on the land, we did not pay much attention to the core business, which was deteriorating and we ended up losing money,” says Dhawan.

Despite the ups and downs, Dhawan has done well — the fund is up 70% in absolute rupee terms at a time the market has remained at nearly the same level. “It has been a very volatile, roller coaster type ride. We have done reasonably well versus the market. In absolute terms, it is not great. We aspire for much better returns.”

No free lunches

It was time up for questions. And no one would leave empty handed. Apart from the infinite wisdom and the experience of meeting the legend, every student got a Berkshire goodie bag with a pen, T-shirt, and a pack of Berkshire Hathaway playing cards. Dhawan has preserved the pen and tee as priceless gifts but finally broken out the playing cards. He’s started playing bridge, once again emulating Buffett.

Buffett and the student contingent then headed out for Gorat’s — Buffett’s favourite restaurant. Buffett drove himself to Gorat’s, giving a few students a ride in his car. Dhawan didn’t make it to the car, but at Gorat’s he got to sit right across the legendary investor. “Buffett was being bombarded from all corners, but I had the real estate, so I got to ask the most questions.” You would think that given the opportunity to feast on Buffett’s wisdom, food would have been unimportant. But Dhawan clearly remembers what he ate: steak sandwich. “That’s what everyone ordered because that’s what Buffett ordered!”

Once everyone was done eating, there was an awkward silence as the waitress brought the bill. Buffett continued chatting away with a student as everyone else looked at each other. Finally, the waitress piped up. “If you’re waiting for him to pay, he won’t,” she said, pointing at the big man. The room exploded with laughter. And everyone reached for their wallets. As they walked out, Buffett couldn’t resist taking a few students over to his car to show off his licence plate — it’s a custom plate that reads “THRIFTY”.

The next 10 minutes were spent outside the restaurant clicking pictures with Buffett — he struck his favourite pose, where he pulls out his wallet and pretends to hand it to the person next to him in the picture. Next up was shopping: Buffett had arranged for the students to meet the manager of Nebraska Furniture Mart and asked them to shop generously (Berkshire owns it), availing of the Berkshire discount.

Before they boarded the minibus for the drive back, the Wharton contingent gave Buffett an ovation. He walked across the parking lot, got into his Cadillac and gave one last wave as he drove by. Says Dhawan, “It felt like saying bye to the favourite uncle from out of town you just met for lunch — he was warm, witty and full of good advice. At some point, you almost forgot he was also the world’s greatest investor.”