"We run multiple philosophies and would want the market to rate us on those philosophies and not categories,” states R Srinivasan, head of equity at SBI Mutual Fund, who manages Rs.8,000 crore of AUM across five schemes. It’s not without reason that — ‘Vasan’, what his colleagues call him — has seen both adulation and infamy.

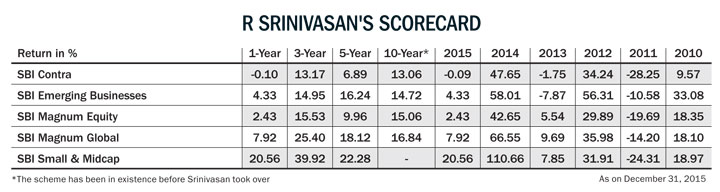

In mid-2009 when Srinivasan moved from Everstone Capital to SBI Mutual Fund as a senior fund manager and was assigned the Magnum Emerging Businesses Fund, it was ranked 41 among the 47 funds in the mid- and small-cap category after a massive 69% fall in 2008. But in the same year when the fund bounced back with a 109% return and over the next three years ended up as the top fund in the mid-cap category with an impressive 56% return in 2012, Srinivasan made headlines in every pink paper. However, following a below average performance with a negative return of over 7% in 2013 and since then, based on the past three-year returns of 12%, the Rs.1,600-crore fund is now at number 63 among the 68 funds in its category, as per Value Research.

“That is because the fund is an absolute return product and that could lead you to periods where you could underperform the benchmark,” explains Srinivasan, who is 8th as per the Outlook Business-Value Research five-year rankings. The other fund that he runs is the Rs.2,470-crore Global Equity Fund which focuses only on quality stocks and is a relative return product. “Companies in this fund won’t face existential issues. They will not suffer if the market falls sharply, but they will not rise either, if the market goes up sharply. Over time, it will fetch you good returns,” assures Srinivasan. He adds how the focus is on stocks with regard to this fund.

The fund house runs two philosophies: large cap (relative return) and mid cap (absolute return). The relative return is based on four factors — sales growth, ebitda margins, volume, and market share changes. “In large caps it is very difficult to have expectations any different from the sell-side which have an in-depth coverage of large caps,” says Srinivasan. As for mid caps, the key factors that the fund manager focuses on are — core competency, competitive advantage in business, minimum growth of 20% and consistent ROC of 20% over a period of time, reliable management and an attractive valuation. “We are not saying that we are buying because of excellent management, by that yardstick one cannot buy anything in India. It isn’t always just black and white, there is always a shade of grey,” he says matter-of-factly. He further elaborates that while the filters for relative and absolute funds are clearly defined, the stocks can be bought for any of the following reasons — market share, brand franchise, cost competitiveness, tech advantage, regulatory edge and network effect.

A mixed basket

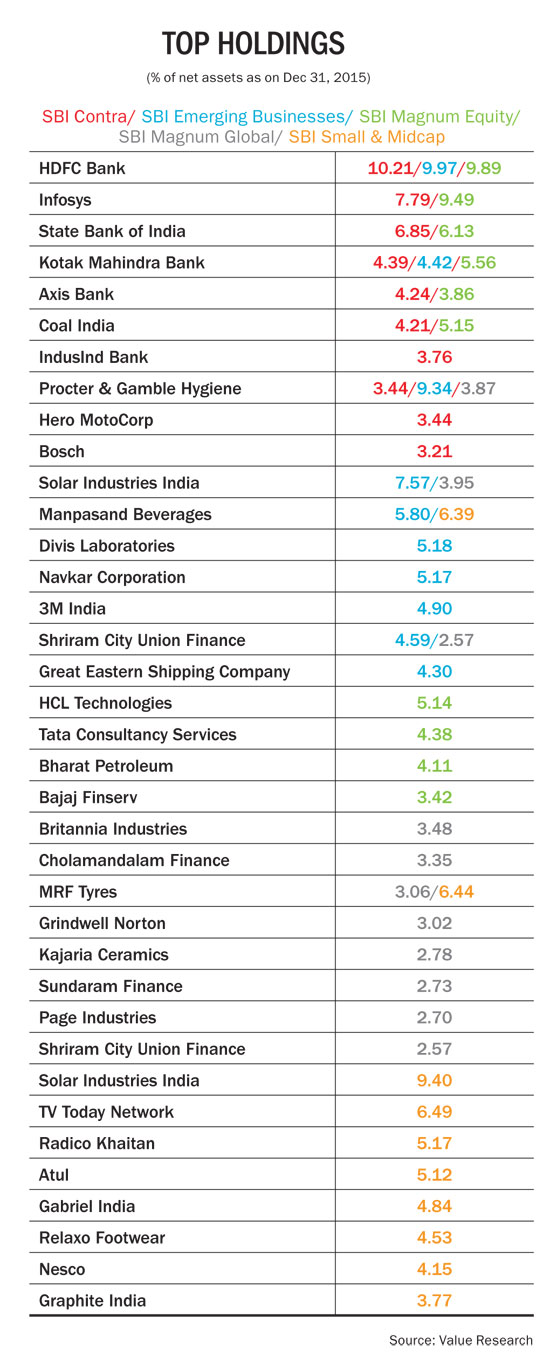

The Srinivasan-run Global Equity Fund comprises Procter & Gamble Hygiene and Health Care (P&G), Solar Industries India, Cholamandalam Finance, Grindwell Norton, Britannia Industries, and Dr Lal PathLabs among the top 10 holdings. While P&G continues to increase its market share in the feminine care market (currently 57%), so has Britannia under new MD, Varun Berry. In the case of Cholamandalam, he believes that even though they are not low on financials, the fund cannot be more than 8% underweight in the sector. Thus, to maintain a benchmark, it had to make a choice. “Shriram Transport Finance is by far the best in the commercial vehicle loan business. That’s because nobody has been able to do what it has done for decades. But Cholamandalam is the only player that has managed to make its presence felt in this business, if Shriram lends to seven of the 10 vehicles funded, the other three will be by Cholamandalam. Then again, we won’t simply buy anything in financials because we need a sector representation…Chola also makes the cut due to its high ROC and better growth prospects,” Srinivasan points out.

Since the emphasis is on quality and high-growth companies in the Global Business Fund, valuations may not necessarily be attractive. He is cognisant about it and defends his position, “In the Global Business Fund, the philosophy is more important than price. While quality is not a function of price, recommendation is always a function of price. So, at these levels, the sell-side could have a “sell” call. P&G may underperform the market for three years, but it will not give a negative return of 50%. Stocks that can deliver 500% may also fall 90%, like we had seen in the case of JP.”

Though P&G with an impressive portfolio comprising Whisper — India’s leading feminine hygiene brand — Vicks and Old Spice, is trading at 40x one year ahead, Srinivasan claims that the best is yet to come. “I strongly believe in the structural growth story of P&G that will be driven by low market penetration in the feminine care segment [two-third of sales] of around 15%. In addition to this, its distribution reach and diverse product portfolio make for higher entry barriers," he says. Despite the presence of Johnson & Johnson and attempts made by Emami to enter the sanitary napkin space, they have not been able to snitch market share from P&G. “There is a huge amount of brand stickiness and as more and more women move up the affordability curve, brand aspirations will continue to rise. It’s not exactly getting commoditised as there is a tech edge which other domestic players can't match up to,” says Srinivasan. In fact, for the just concluded second quarter, the company posted a 62% jump in net profit to Rs.147 crore riding on the back of a 11% rise in total income to Rs.734 crore, with double-digit growth in Whisper’s sales.

Srinivasan’s firm belief in P&G’s future performance stems from the way his bets on Page Industries, TTK Prestige and Hawkins have played out in the past. At 2.6% of assets, Page Industries continues to sit pretty in the top 10 holdings of the Global Fund and has returned a whopping 1100%-plus return since 2010 at the current level of Rs.10,750, that is after the stock hit its closing high of Rs.16,860 in mid-2015. “When we tanked up on Page it was an illiquid stock and to be honest, we didn’t expect the story to play out the way it has. When we bought it in 2009 at Rs.600-650 levels, right up to Rs.1,200, we expected it to double in three years with an earnings growth of 25%. What was clear to us was that the growth was occurring in the men’s category, but we never imagined that subsequently all its products — shorts, tracks, swimwear and women’s wear — would hit the big time,” explains Srinivasan. Though the management in Page has been paring down its stake from 65% in 2009, to 51%, as on date, Srinivasan is not too worried. “As long as the management continues to be a majority stakeholder after selling, you don’t panic. Especially in mid caps, if a promoter hasn’t seen so much wealth and observes a chance to make some money, it’s quite natural. It’s human nature.” The fund manager too has trimmed his position in the stock from 2.72 lakh shares to 50,000 shares.

Another multi-bagger that he took a while to identify was Eicher Motors, which the fund had held at a certain point of time. “I still remember, I was at a signal on my old Bullet, when a couple of guys offered me Rs.30,000 for the 25-year-old vehicle. I didn’t expect the motorcycle business to take off the way it did under Siddhartha Lal. I had bought the stock because it had cash on its books. But once things played out, I ended up looking smart with my purchase,” he smiles.

Another stock that has found its way into three of Srinivasan’s schemes is Solar Industries India. It currently boasts of a 30% market share in India and a 57% market share in the exports of industrial explosives, making it the largest manufacturer of industrial explosives and initiating systems in India. It is present across the product value chain comprising bulk explosives, cartridge explosives, detonators, detonating cords, cast boosters, PETN (raw material for detonators) and HMX (warhead in missiles). During FY09-15, even as coal mining production grew at 3% CAGR, the company saw a volume CAGR twice that of the overall industry at 6%. “Solar Industries has a huge cost advantage besides its 20-25 factories,” points out Srinivasan. With the revival of demand in infrastructure and pending demand from recently awarded mines in the coal auctions, a strong pipeline of new tenders is expected in the coming years. More importantly, return ratios, which had dipped to 19% (RoE) and 17% in FY15 — as the company incurred capex due to increasing capacity and foraying into the defence business — are expected to improve going ahead. Srinivasan holds close to 21% of his three scheme’s assets in the stock, which also happen to be the fund’s top holdings.

In the Emerging Business Fund, Srinivasan has loaded on quite a few stocks that recently went public such as Manpasand Beverages and Navkar Corporation. Apart from looking at their balance sheets, Srinivasan attempts to thoroughly understand the businesses he invests in. “In Manpasand, we have bought 8% in the fund across categories, except the Global Fund, as we couldn’t justify it on the competitive advantage aspect,” reveals Srinivasan. The Gujarat-based fruit drink manufacturer earns 97% of its revenue from the mango-based fruit drink ‘Mango Sip’ (with ~12-14% mango pulp content). Manpasand Beverages’ brands are present in 24 states through over 200,000 retailers, 2,000 distributors and 200 plus super stockists. Its products are primarily consumed in semi- urban and rural markets.

The company has two manufacturing facilities at Vadodara in Gujarat, one each at Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh and Dehradun in Uttarakhand and another is being set up at Ambala in Haryana. The beverage-maker deploys an innovative strategy to sell its products. It offers distributors higher margins of up to 15% by funding their vehicle purchases, paying for fuel and driver charges. “In doing so, it doesn’t spend on advertisements and manages to sell its products to places where Coke and Pepsi are sold,” explains Srinivasan. During the non-summer period, to keep the momentum going, it sells to the railways. “The best part about the company is that the promoter is passionate about the business and is a big admirer of BM Vyas, the man credited with transforming the Gujarat Co-operative Milk Marketing Federation into a Rs.10,000-crore brand, Amul. The company has managed to get Vyas on board as a whole-time director,” he adds. On a Rs.360-crore top line, the company earns a profit of Rs.30 crore. Srinivasan has allotted 5.80% of the Emerging Businesses Fund assets to the stock, which has gained Rs.46 to Rs.440 since its listing in mid-2015.

In the case of Navkar Corporation, the Maharashtra-based company owns container freight stations (CFS) in Panvel at close proximity to the Jawaharlal Nehru Port, the country’s largest container port. While the three CFS’ aggregate handling capacity stands at 310,000 TEUs (Twenty foot equivalent units) per annum, the company’s biggest advantage is that it has a private railway freight terminal, which allows them to load cargo from container trains and transport domestic cargo from inland destinations on the Indian rail network. It owns and operates 516 trailers for the transportation of cargo. “The company makes a decent ROC and has good assets with another inland container depot coming up in Vapi,” says Srinivasan, who has bet 5% of the Emerging Businesses Fund assets on this stock that made its debut on the Street in mid-2015.

Among the new entrants in the stock market, Srinivasan has purchased 6.2 lakh shares of Dr Lal PathLabs, which listed in December 2015. He predicts that the diagnostic chain will eat into the unorganised market. “While blood testing is a highly commoditised business, the company has created a niche for itself in the biopsy space. More importantly, it makes a decent ROC of 35% on capital employed,” says Srinivasan. But he is also cognisant of the fact that the growth story is still a few years away and he is accordingly building that into his portfolio construction. “You can create a pocket for such stocks where you should be ready to say that I won’t make money on 15% but on the rest 85% I will manage to make money and stay in the top two quartiles. And then if I am right, the 15% will be my biggest driver,” he says.

Learning curve

Apart from riding on the high of making successful bets, there have also been instances where stocks have not performed the way he had envisaged. In 2012, when Srinivasan picked up SpiceJet, his reasoning was that the bleeding airline would be taken over by a bigger airline, with the Marans selling out. Since that didn’t happen till 2015, Srinivasan had exited the stock with a loss before that.

Interestingly, it was when Ajay Singh was still a partial owner of the low-cost carrier that the fund manager had entered the stock. “Ajay Singh is brilliant, I should have got in again when he bought back his stake, but I was so screwed up because of the earlier loss that I did not consider the opportunity,” he admits. Similarly, JP and Wockhardt are the other stocks where the fund manager did not make money.

It is to avoid such cases that the fund house has well-defined templates in place. Srinivasan points out that no one can deviate from the investing framework that the fund house has created since its revamp in late 2008. It is around this time that SBI Mutual Fund implemented a few changes — it got a chief investment officer in Navneet Munot, set investing templates for 70% of the schemes, which at that point looked all the same. “Each fund manager is tied to that template to ensure consistency,” explains Srinivasan. In addition to these steps, analysts were accorded more importance than the fund manager and in doing so it created a culture of ownership and accountability. “These three things have an element of sustainability which keep the fund house and its schemes functional even if I were to quit and go. That is what an investor wants. These guidelines ensure that there are no star fund managers but just an investing philosophy that investors trust.”

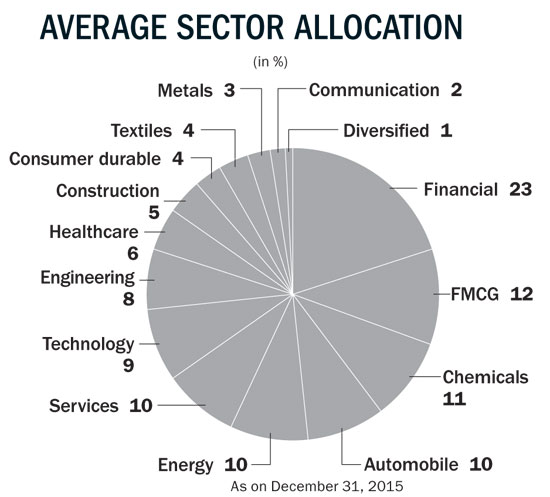

Not surprising then that Srinivasan loathes the crystal gazing on which way the wind is blowing on the Street. “I have an eye on stocks and not on the market because there are too many moving parts at play, which you have no knowledge about. However, from a thematic perspective, as a team, we like consumption and manufactured exports. We are overweight financials, energy and industrials and underweight utilities and consumer staples. This is not a five-year view, but it’s pretty dynamic,” he concludes.