There is nothing extraordinary about the conference room at Chaman Lal Setia Exports’ Gurgaon office… in terms of appearance, atleast. However, if you pay close attention to the conversations of the promoters spanning two generations, then you might be able to piece together the reason behind the firm’s impressive growth over the past five decades.

Rajeev Setia, executive director and one of the founding members of the company speaks in fluent Punjabi with a trader over the phone. At the other end of the table is his son, Sankesh Setia, who’s trying to resolve an issue with an international order. And he sounds like any other professional business manager. While both are executive directors of the firm, each of them has their unique way in which they go about business; that mixed approach of the old and new generation is what has helped the basmati rice exporter survive and thrive amidst changing times. Basmati rice is a common heritage that India shares with Pakistan with both the countries accounting for 70% and 30% production of the grain respectively.

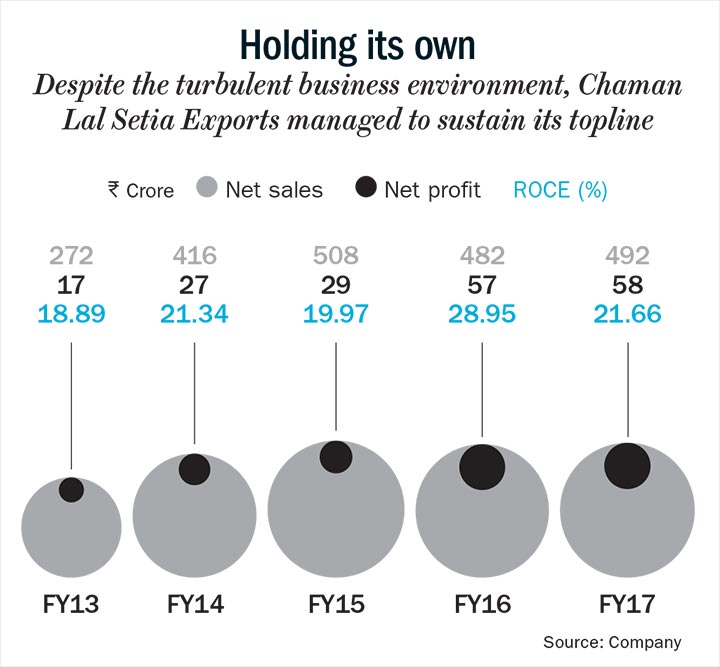

“The entry of the next generation has made a big difference to our business. They are way more organised and aggressive,” says Rajeev, who oversaw the transformation of the rice mill into an export house back in 1982 along with his brother, Vijay and father, Chaman Lal. And he is now joined by his sons Sankesh, Sukarn and nephew, Ankit. However, the emergence of the next gen isn’t the only reason this family run-company has done well in the past five years. The miller that markets the Maharani rice brand witnessed a rise in revenue from Rs.218 crore in FY13 to an estimated Rs.750 crore in FY18.

Tilling the soil

It was in 1974 when Chaman Lal Setia started a rice mill in Amritsar, Punjab. Despite being just college students at the time, both his sons would partake in the mill work as well. Rajeev recalls how within just three years of establishing the mill, they were endowed with a government legislation that enabled them to sell their grains across the country, unlike earlier where it was controlled by the government.

And then rice exports being given a green signal in 1980 gave a huge fillip to the budding businessmen. It took the trio only two years to clinch their first breakthrough in the form of a huge order from a Singapore-based customer. Thirty-six years later, Rajeev still remembers every detail of that trade, “The first consignment was 720 bags of 25 kg each. The total quantity was 18 tonne, and it cost Rs.135,000.”

Securing orders in the international market was no easy task though. Rajeev recalls the pain points then, “We had no way to send a fax back then and emails were not yet the order of the day. We would write letters to prospective clients and await their response. We’d scout the offices of embassies and chambers of commerce abroad. The Singapore client was bagged during one such survey”.

But things were looking good by 1989, when Chaman Lal Setia was officially deemed an exporter. However, back home in India, the northern state of Punjab was dealing with militancy. With the family having lived in Amritsar for decades and the mill being located there as well, the Setia clan didn’t see any reason to move base until 1991. Vijay recounts the events of that unfortunate day when the two brothers were attacked, “Our vehicle was ambushed by terrorists. They shot at both of us and one of my lungs was ruptured.” But the duo managed to disarm the attacker with the licensed firearm they were carrying and averted further damage.

It didn’t take them too long thereafter to shift base to Karnal in Haryana in 1993. And since the mill was already sourcing the crop from the region, it didn’t present any new challenge. In 1995, the company went public and raised Rs.23 crore. Moving to Karnal proved helpful for the business as well. Vijay, who is also the president of the All India Rice Exporters’ Association, managed to get hold of agrarian scientists in the city thanks to the presence of several agri institutions such as the Central Soil Salinity Research Institute and the National Dairy Research Institute.

This encouraged the economics graduate to invest time and resources in understanding more about rice grain. And that eventually led to the promoter developing innovative techniques to improve various processes in the business. “I wanted to understand the science behind our work. I engaged a scientist from Pusa in Delhi for three years to learn more about post-harvest technologies,” says Vijay. He pursued this for several years and that resulted in him filing four patents on the subject.

“In rice milling, you need to heat every batch with 50,000-100,000 litres of water. I invented a technology by which we could reuse this water.” Apart from developing this technique that has helped the mill save plenty of water, he also worked on ways to retain the optimum quality of the grain by controlling the warehouse temperature. “In India, parboiling and paddy drying usually takes place in open areas. The grain reacts to fluctuations in temperature and loses its consistency. Six years ago, we introduced a system of storing grains in a controlled temperature at the warehouse”.

Ready to germinate

Apart from the promoters taking a keen interest in research that benefitted their trade, an unwavering focus on diversifying its client base has held the company in good stead. Rajeev recalls how the founders would go about their homework in the early days, “We would travel abroad and eat in an Indian restaurant two-three times before befriending the owner. Then he would tell us from where he bought rice. That was how we would trace the buyers in each country.”

But Rajeev’s tech savvy sons and nephew have found more ways to enhance this process. “We ensure we travel every month or at least every second month. We identify countries where we don’t supply yet and put that on our radar,” explains Sankesh. The company recently participated in exhibitions such as the Gulf Food exhibition in Dubai, similar trade fairs in Egypt and Iran. In a bid to spread the word far and wide, it has also organised similar events in Africa.

“Unlike earlier, we are not in our target countries only for three-four days, we spend 10 days at least, we add new customers also. When the promoters themselves travel scouting for customers, it leaves a different impression on the prospective buyers,” he adds. Before the third generation came onboard in 2008, the basmati rice exporter was supplying to 50 countries and that number has gone up to 80 now.

The strategy doesn’t stop at just adding another country to the list, it involves going after multiple clients once a new market has been discovered. Sankesh explains how it’s a natural progression, “If we supply 100,000 kg in one country, almost 50,000 customers will end up consuming that rice. That’s a massive number of people who will provide feedback. If they appreciate the quality, other importers will also be interested.”

He further elucidates that there are two types of customers in terms of the business provided — the first place orders in the range of Rs.50 lakh-5 crore. And the second lot falls in the range of Rs.25 crore-50 crore. Chaman Lal Setia receives 70% of its orders from clients in the first range, while the remaining comes in from big buyers.

Typically a big buyer can squeeze you (may not always be true, but mostly). However, multiple small and mid-sized buyers provide a safety net, as well as better margins. “Our margins are better than our competitors because of this strategy,” claims Sankesh. For instance, Iran which is the largest consumer of Indian basmati rice provides small orders worth Rs.25 crore, while a bigger consignment could fetch as much as Rs.200 crore. Although he adds that the company has stopped relying on Iran due to the frequent imposition of sanctions.

Like several other rice exporters, Chaman Lal Setia sources its grains from farmers in Punjab, Haryana, and western Uttar Pradesh. A miller has very little control over the variant and quality of the paddy cultivated. “We work with commission agents, who help with sourcing from farmers. The Indian Institute of Agricultural Research releases new varieties of basmati. But that adoption at the farm level takes time,” explains Vijay. Brother Rajeev also emphasises that they are prompt with payments, “We don’t default. That way you get a good price from the farmers as well.”

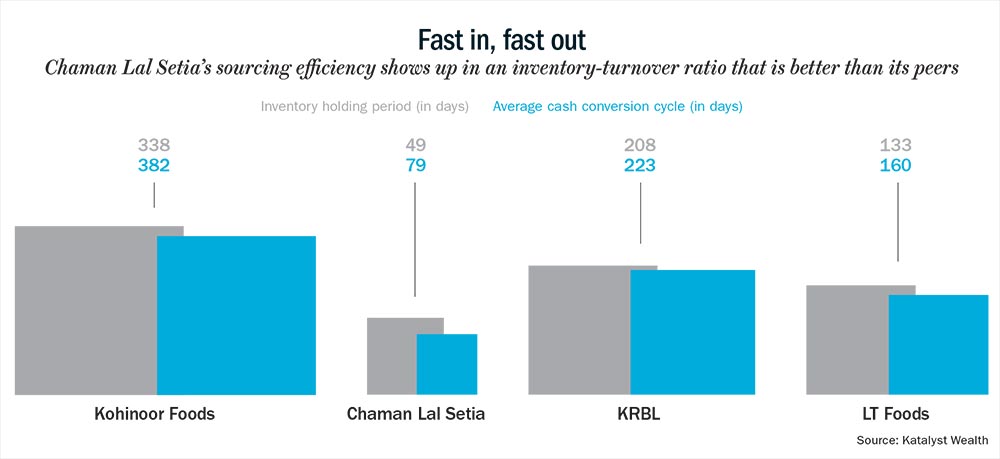

The management refuses to reveal names of countries that contribute the most to the company’s revenue but in general, Iran and countries in West Asia have been the largest buyers of Indian basmati variety. Ekansh Mittal, founder, Katalyst Wealth, who tracks the stock explains, “Other major players in the basmati exports space follow a model that is manufacturing-intensive. They have huge capacity and maintain large stockpiles. On the other hand, Chaman Lal Setia doesn’t operate with that kind of capacity and instead procures a lot of semi-processed rice. So growth is not subject to capacity. But it is about exploring new markets, and clients. If it is able to continue winning new customers, it will grow.”

Battling headwind

The past five years have been nothing but turbulent for the basmati rice exports industry. There have been temporary import bans from countries such as Iran, which happens to be the largest importer of this variety of rice. Consequently, a lot of basmati rice exporters have shut shop. REI Foods, which was a listed entity and claimed 22% of global exports at one point, filed a liquidation plea last year. Bush Foods, a Haryana-based export house, in which a Qatar company invested Rs.540 crore in 2013, went bankrupt amidst a charge of fudged accounts. The Delhi-based flour brand Shakti Bhog Foods also entered basmati exports but soon folded up operations.

Rajeev reflects on why several of his peers didn’t do so well, “Given that it is an agri business, there has to be harmony between your capacity to source, process, sell, and the purchase/sale price. A lot of these players have not been able to do that.” Most of the casualties have been mills in Haryana and Punjab, who were engaged in basmati rice. Almost 90% of this variant of rice is consumed in West Asia. “If you have a presence in fewer markets and have limited buyers and if sanctions are imposed on those nations, then demand is disrupted. In 2015, the United Nations called for sanctions on Iran, due to which the country couldn’t pay Indian basmati exporters. The entire payment cycle was disrupted. Prices dropped sharply due to the glut in the domestic market. Around 30-40% of the market was blocked due to Iran’s inability to pick up stock,” explains Ashok Agarwal of KLA Group in Uttarakhand. That eventually resulted in inventory being carried forward to the next year. “This was the primary reason why the mills shut down and some of them were already facing financial issues.”

Chaman Lal Setia’s sales stagnated to Rs.500 crore in the past two years, but the Setias are hopeful of that number rising to Rs.750 crore for FY18. Of this, about 75% is contributed by exports alone. Mittal further expands on why the other mills have closed while Chaman Lal Setia managed to tide over troubled waters, “It is a highly capital-intensive business. Many players created huge capacities leading to oversupply and when demand slumped, they went bust. On the other hand, Chaman Lal Setia’s asset-light model helped it remain debt-free. Its inventory turnover ratio is higher than KRBL and LT Foods.”

Sankesh attributes part of the spurt in revenue to the suspended operations of the other mills. However, diversification continues to be the reason that Chaman Lal Setia has managed to stay afloat. Vijay feels that while there have been attempts to tap markets across the world, there might be a positive development from neighbouring giant — China. “They consume sticky rice, but in some regions they are also opening up to long basmati rice. It can be a big market for us in the future,” he says with hope.

The past may have been muddled with instability for rice exporters in India, but the future certainly looks bright. Chaman Lal Setia Exports seems to have smartly grown with a low-risk diversified model. But Mittal points out a downside to this approach, “It has not invested so much in the brand ‘Maharani’. If you look at KRBL and LT Foods, their brands are very strong and that gets them a premium. Their gross margins are around 30% while it’s 20% for Chaman Lal Setia.” However, for now, the Setias seem to be content with a model that has insulated them from the vagaries of the trade, and delivered growth year after year.