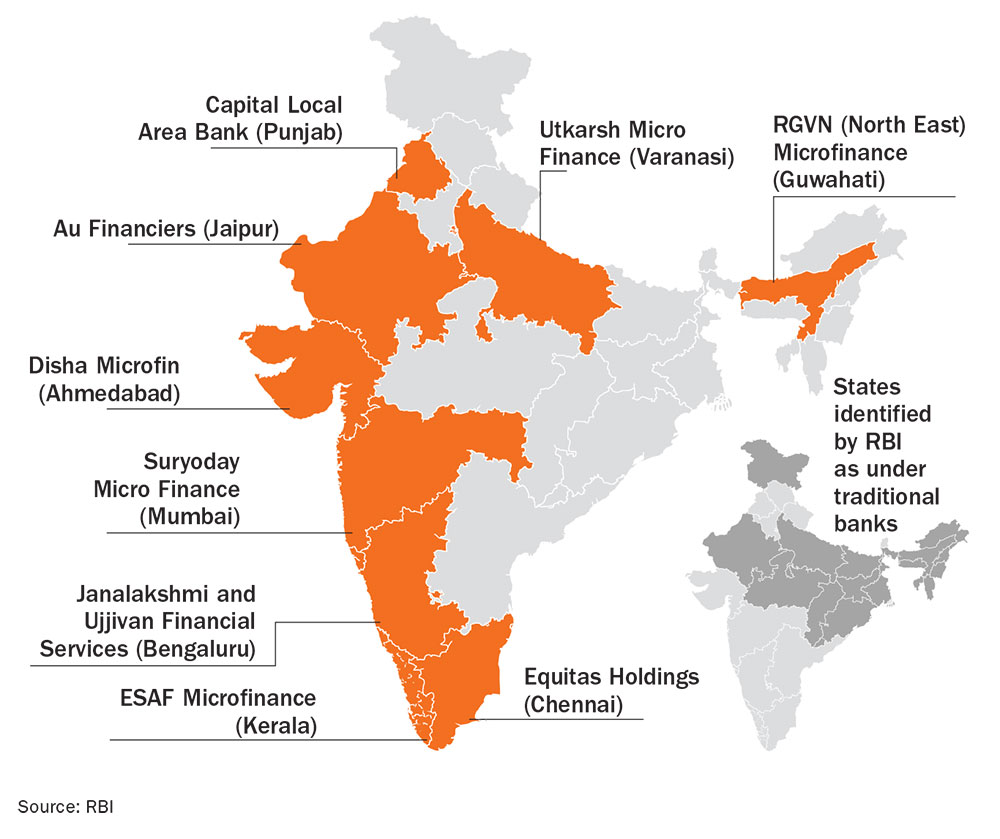

With the massive number of unbanked and underbanked individuals across India in mind, the RBI in August 2013 released a discussion paper titled Banking Structure in India — The Way Forward. Taking this concept a step further, it in September 2015 issued in-principle licenses to 10 entities for setting up small finance banks (SFBs) and 11 entities for payment banks; the regulator plans to hand out licenses on tap if all goes well. While most media attention has been focused on payment bank licensees, which comprise some of India’s biggest corporate names, conversation about SFBs, which include eight microfinance institutions (MFIs), one local area bank and one NBFC, has been subdued (see: Here, there, everywhere). Unlike payment banks, which aren’t authorised to lend, SFBs are full-fledged banks (albeit subject to certain restrictions) meant to further financial inclusion by provision of savings vehicles and supply of credit to small business units, small and marginal farmers, MSMEs and other unorganised sector entities. Consequently, not just are SFBs subject to all regulations pertaining to commercial banks, they are also required to extend 75% of credit to sectors classified as priority sector lending by RBI. Also, at least 50% of their loans portfolio should constitute small-ticket loans of up to Rs.25 lakh.

In a country where financial inclusion statistics are dismal, the opportunity for SFBs, many of whom are also experienced MFI players, is massive. According to an RBI report, 43.9% of all rural households rely on non-institutional sources of cash credit like professional moneylenders, who charge predatory interest rates. The Committee on Financial Inclusion headed by C Rangarajan notes, “…despite the vast network of bank branches, only 27% of total farm households are indebted to formal sources…” There are also large regional discrepancies, with the northeastern, eastern and central parts of the country losing out in particular. The Fourth Census of the MSME Sector in 2009 also noted that only 5.2% of all MSME units availed of credit through institutional sources. While the opportunity in this segment is huge, SFBs have to contend with a crowded competitive landscape: an RBI report contends that there were — at the beginning of FY14 — nearly “64 regional rural banks, 1,606 urban cooperative banks, 31 state cooperative banks, 371 district central cooperative banks, 20 state cooperative agriculture and rural development banks and 697 primary cooperative agriculture and rural development banks”.

But an industry expert who does not wish to be identified says that despite these challenges, SFBs will have a clear path to profitability while morphing into full-fledged banks. “Our intention is to be a full-fledged financial services provider to the financially excluded. We have decided to adopt the three-tier structure recommended for universal banks and have set up a separate team to manage this,” says VS Radhakrishnan, MD, Janalakshmi Financial Services, the largest urban MFI in India, with AUM of Rs.3,800 crore and a customer base of 2.3 million across 233 branches. The three-tier mention refers to the ownership structure followed by universal banks, with the promoter at the top, followed by the holding company and then various subsidiaries.

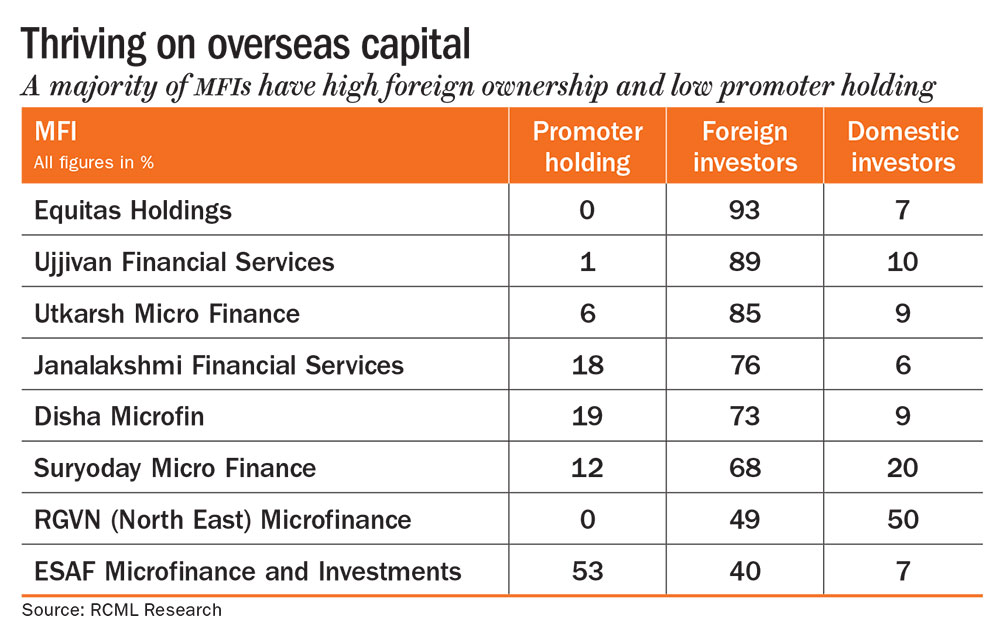

“Our interactions with NBFC-MFIs that have won SFB licences suggest that they will be able to transition into banks smoothly without any impact on loan growth. Sustained loan growth is essential considering these banks will have to raise massive amounts of domestic equity to comply with RBI norms,” observes a Religare report. These norms specify a paid-up equity capital requirement of Rs.100 crore, of which a minimum of 40% must be the promoter’s initial contribution. Also, the promoter entity must be owned by resident Indians and foreign ownership shouldn’t exceed 50%. However, most licensees have low promoter holdings and large foreign stakes (see: Thriving on overseas capital), requiring them to dilute the latter.

“The next 18 months are going to be a lot of hard work. We are looking for ways to bring down the 90% foreign shareholding in the company, including private placements,” said Samit Ghosh, founder and MD of Ujjivan Financial Services, to a national daily shortly after the licences were issued. Rajeev Yadav, MD, Fincare, which owns licensee Disha Microfin, says his company might go down the same route. Of course, there are SFBs that have taken the public offering route. Chennai-based Equitas Holdings, for one, raised around Rs.2,176 crore through an IPO, bringing down its foreign ownership from 93% to 35%. Reports indicate that Ujjivan might also come out with an IPO in the near future. “Unless high growth rates are maintained, such heavy dilution will result in low RoE, which may not go down well with existing PE investors,” cautions the Religare report. However, the dilution is essential since SFBs transitioning to universal banks “would be subject to… minimum paid-up capital/net worth requirements as applicable to universal banks”.

“The next 18 months are going to be a lot of hard work. We are looking for ways to bring down the 90% foreign shareholding in the company, including private placements,” said Samit Ghosh, founder and MD of Ujjivan Financial Services, to a national daily shortly after the licences were issued. Rajeev Yadav, MD, Fincare, which owns licensee Disha Microfin, says his company might go down the same route. Of course, there are SFBs that have taken the public offering route. Chennai-based Equitas Holdings, for one, raised around Rs.2,176 crore through an IPO, bringing down its foreign ownership from 93% to 35%. Reports indicate that Ujjivan might also come out with an IPO in the near future. “Unless high growth rates are maintained, such heavy dilution will result in low RoE, which may not go down well with existing PE investors,” cautions the Religare report. However, the dilution is essential since SFBs transitioning to universal banks “would be subject to… minimum paid-up capital/net worth requirements as applicable to universal banks”.

Money, money, money

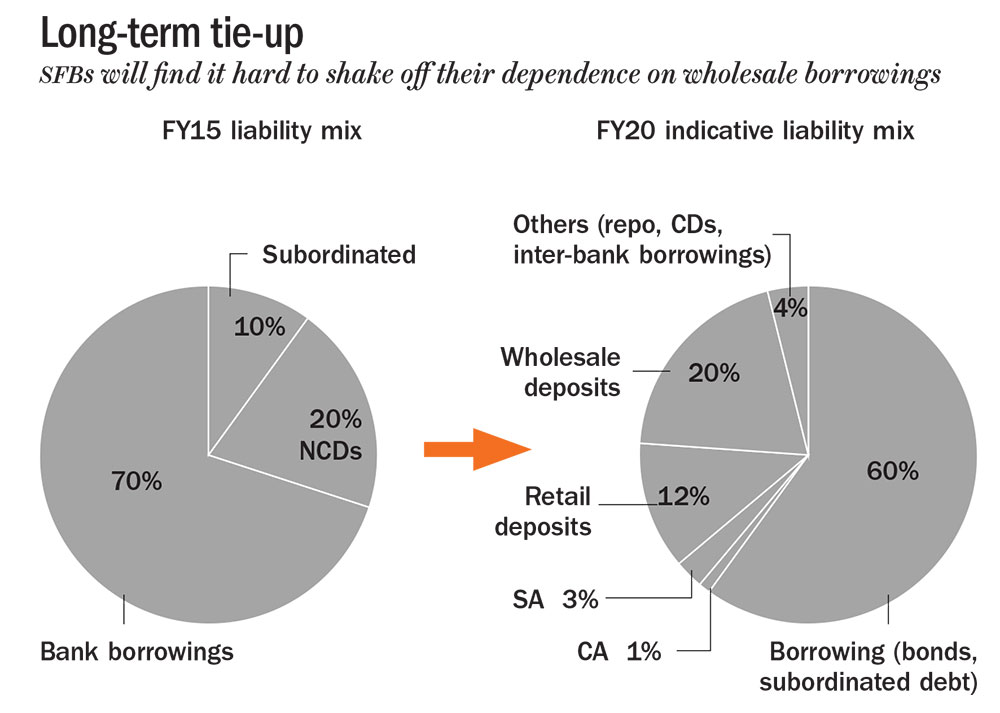

But restructuring their holding structure is just the first step for SFBs: they also need to focus on liabilities and raise deposits to reduce their cost of borrowing to lower the interest rates they charge. Access to public deposits will allow SFBs to lower their overall cost of borrowing. According to Religare, bulk borrowing by SFBs incurs an interest rate of 10%, while retail term deposits and savings accounts incur 9% and 5%, respectively. “There are going to be two main drivers of cost reduction: one, becoming a rated bank from a rated NBFC, so that there is a reduction in cost of funds due to the improved rating. Then, there will be structural benefits from being a bank, including access to inter-bank markets. So, the immediate reduction in cost of funds will be led by these structural factors, whereas the harder, longer path in the form of low-cost deposits will take some time,” says Bindu Ananth, chair, IFMR Trust (see: Long-term tie-up).

“We have to start thinking about how to start business on the deposit side. We’re going to offer a basket of products to our customers: savings, deposits, insurance and remittances. Our strategy is to focus on semi-urban and rural customers,” says Yadav of Fincare. However, the average ticket size of savings accounts in rural India is only 1/3rd and 1/4th of urban and metropolitan geographies, according to a report by Chennai-based Spark Capital. “Since average deposit size is going to be smaller than private universal banks, our goal is to build a large customer base,” adds Yadav. According to Spark Capital, the FY18 deposit strategy for SFBs is going to consist of “focusing on existing customers for liabilities by leveraging the business correspondent model, collecting daily recurring deposits with ticket sizes of Rs.50-300 per customer, and some incremental focus on wholesale deposits”. In FY19, SFBs are going to “differentiate by offering higher rates (of 9-11%) on wholesale and retail term deposits”. However, small ticket sizes might queer the pitch: the cost of maintaining such accounts is large, thereby rendering the maintenance costs higher than the SFBs’ cost of borrowing, making higher interest rates unviable.

“While our primary focus is going to be on savings, recurring or term deposits, some part of our semi-urban SME strategy could result in current accounts,” says Yadav. Adds Radhakrishnan of Janalakshmi, “While we are keen on providing savings solutions to our target segment, there is an opportunity to raise deposits from other customer segments as well. Our strategy will be to leverage a larger footprint and focus on customers.” But the current account push might not be a large one. “84% of current account balances reside in urban/metropolitan India. Given the primary area of operation and existing business model, traction in current account deposits is unlikely,” says the Spark Capital report. “While we will have a focus on current and savings accounts, we expect that this will build up over a period of time and will not be comparable with established commercial banks,” agrees Radhakrishnan.

Explains Ananth of IFMR, “While SFBs offer an important opportunity for savings collection from excluded groups, this is not low-hanging fruit. It will take some time to build this business, since these are customers who save small amounts on a regular basis for a long period of time. So, it will be a while before momentum picks up and translates into a meaningful savings balance.” Yadav elaborates on how his company plans to convert MFI customers into depositors, “The first thing we will do is that instead of giving out cash to MFI customers, we will deposit credit into their savings accounts. While our customers aren’t well off, they’re not living hand to mouth. Each of them has some savings potential — some liquidity as a safety net — to service installments and take care of emergency needs. This liquidity can be brought into the savings account, provided it is conveniently accessible to the customer. If we bring in convenient cash in-cash out points, they will be incentivised into opening savings accounts that also pay interest.”

Kshama Fernandes, CEO, IFMR Capital, gives the example of Bandhan Bank, an MFI based in east India, which commenced banking operations in August 2015 and has since raised deposits worth Rs.11,000 crore, 1/3rd of which have been from retail depositors. “Bandhan has already demonstrated the ability to raise deposits from its client base. MFI borrowers require a savings product as much as they require loans. So, this is clearly an attractive deposit base. Given that a large portion of potential SFBs are MFIs, the customer profile, ticket size of deposits, their ability to control operation risk and deal with cash will all be of great value as they scale up their deposit base,” she says. Industry experts say rural banks have mainly failed in garnering deposits because of their branch-based approach towards banking. After all, low-income customers can’t afford to forgo a day’s productive labour in visiting a branch located kilometres away.

“The doorstep model works best when the customer profile requires high touch-points and engagement, as in the case of MFI customers,” says Fernandes of IFMR Capital. So, SFBs are leveraging technology to enable doorstep banking. “All of our field workforce will be equipped with mobile solutions in the form of tabs. This, combined with Aadhaar and e-KYC, will enable them to perform basic data entry operations, open accounts and originate loans instantly, while also acting as cash in-cash out points,” says Yadav of Fincare. To achieve this, he plans to double Disha’s feet-on-the-street from the present 2,000 to 6,000 by the time Disha starts operations. “Given the low ticket sizes, a challenge for all SFBs will be to bring down their operating expenses to make their business viable. Robust and scalable technology solutions will play a big role here,” adds Fernandes. That said, it is actually wholesale deposits that will form the bedrock of the liability story for SFBs. “70% of term deposit accounts reside in the ‘less than Rs.100,000’ category, but account for only 13% of outstanding term deposits. The average ticket size for rural India is a third of the national average, leaving limited scope for SFBs to tap into retail term deposits. SFBs will, therefore, be significantly wholesale deposit-funded,” notes the Spark Capital report.

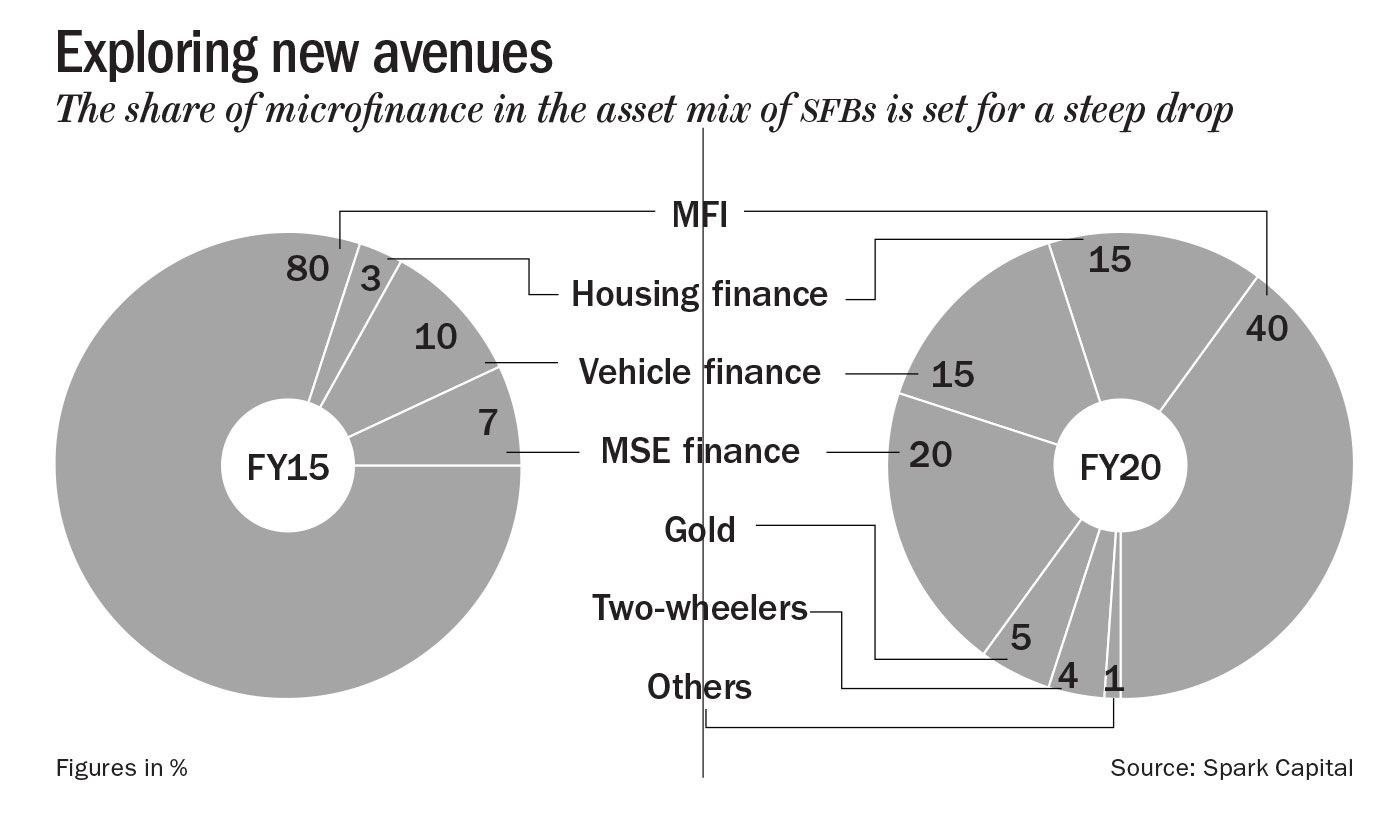

However, analysts point out that even for this, SFBs will have to overcome challenges such as the counterparty exposure limits of insurance entities, mutual funds and corporates. On the asset side, the story is going to be dominated by the SFBs diversifying their product portfolio. “We expect the share of MFIs in our asset mix to reduce significantly and to have a more balanced distribution. We will remain primarily an ‘inclusion player’ but will also focus on other inclusion opportunities such as micro enterprises and affordable housing,” says Radhakrishnan of Janalakshmi. According to Spark Capital, the share of micro-finance in the asset mix of SFBs will fall from around 80% in FY15 to 40% in FY20, with vehicle financing, housing finance and MSE finance grabbing significant chunks (see: Exploring new avenues). However, this diversification is likely to bring down overall yields as the share of high-yielding MFI reduces, says Spark Capital. “Our sensitivity tables suggest a 30 bps erosion in return on assets for every 10% decline in the MFI portfolio, given decline in net interest margins, which are already challenged because of negative drag on cash reserve and statutory liquidity ratios,” it says. But Yadav of Fincare insists, “Yields may be high in MFI, but so is cost of servicing. So, overall, we are not bothered about return dilution.”

The other reason Yadav seems unfazed is because an SFB license opens up the opportunity to offer a “hundred different products”. “However, we want to be focused and not get tempted by these opportunities. We want to focus on one or two simple products such as cross-selling of FMCG products or financial services products. We are already selling national pension scheme products along with solar lantern options, given that power is not regular in rural areas. When we look at fee incomes, we look at these, but as a bank we want to focus on getting the right financial products to our customers, and that’s what our research is going to concentrate on over the next four months,” he says. “In our attempt to be a full financial services provider, the focus will be on the payments business and third-party product distribution,” adds Radhakrishnan of Janalakshmi. Of course, it doesn’t help that payments banks will be competing directly with SFBs for the payments business — including remittances — and to cross-sell third-party products, and SFBs, with their deep hinterland connect led by a feet-on-the-street model, are set to offer a tough fight. It remains to be seen who will be the last man standing.

Banking 2.0

While RBI’s strategic geographical distribution of licences has ensured that SFBs are not in direct competition, the verdict is still out on whether NBFCs and regional banks are going to feel the heat. On their part, SFBs insist that the financially excluded opportunity is massive and competitive jostling will be minimal. “30-40% of expansion might be competitive in nature, but 60% will be based on doing things banks haven’t focused upon. Sure, there might be some degree of competition with regional banks and PSUs, but we can attract customers with better services and products,” says Yadav of Fincare. In agreement, Spark Capital claims there is little intersection between the portfolios of regional banks and SFBs, and that competition is likely to spill over to the NBFCs, which will be directly competing with SFBs for vehicle and SME financing (see: Not quite out of the way). “Banks have not ventured into this space given the unsecured nature of the product, high operating costs and deep hinterland feet-on-the-street sales and collection mechanism required. Therefore, we see negligible impact on regional private banks, given the mutually exclusive theatre of operation,” says the Spark Capital report.

Today, poor data is one of the biggest reasons why banks find it difficult to underwrite loans. “SFBs will drive inclusion, helping India move from a cash economy to a cashless economy,” says Sharad Sharma, co-founder, iSPIRT. Sharma reasons that with the rise of mobile payments for daily transactions, small shop-owners and merchants will have the incentive to create a digital trail for their transactions. He claims this has already happened with Flipkart and Amazon merchants, who, armed with a credible transaction history, have turned credit-rich. “The only reason a hawker will accept payments through mobile is because he wants to create a digital trail so he doesn’t have to take a loan costing 1-4% a day. If he can convert even 50-60% of sales to digital sales, he will get cheaper loans. That will be his motivation to move sales online, and SFBs will be the ones catering to him,” he explains. It may seem like a foregone conclusion that whosoever may lose in the competition, the customer will certainly win, but it’s the only correct one at this point. Then again, the rise of SFBs is good news for everyone; after all, bankers across the spectrum do like to point out, “What’s good for the customer is good for the industry”.