2024 was a year of introspection on the international efforts to tackle climate change. The decisions at the UN’s Pact for the Future, the G20 Rio Leaders’ Declaration and COP29 raise critical questions of the developed world's efforts at limiting temperature rise to 1.5°C by the end of this century. Coupled with this are the uninspiring efforts from both the Global South and Global North to contain their emissions targets, leaving us sceptical if 1.5°C is only a theoretical possibility.

State of the Global Economy

The IMF and OECD project the 2024 global economic growth at 3.2 per cent. The World Bank further states that 2024’s economic growth will underperform its 2010s average in about 60 per cent of economies that constitute more than 80 per cent of the world’s population. The critical reasons for this are geopolitical conflicts, the struggle for recovery from the pandemic, and climate-related disasters. Any success in the world reversing this slow growth now solely rests on the Global South, which, in the coming decades, will be the driver of global growth, consumption, and investment. In fact, over the past 20 years, Global South countries have contributed as much as 80 per cent to global economic growth. However, a global crisis such as climate change disproportionately impacts the Global South.

Climate Action: 1 Step Forward in 2023 and 2 Steps Back in 2024

India’s G20 Presidency (2023)

Both the G20 under India’s Presidency and COP 28 under the UAE in 2023 raised the bar on climate change even amidst turbulent geopolitical challenges. For a year, we witnessed statesmanship from global leaders in their shared vision of global climate commitments.

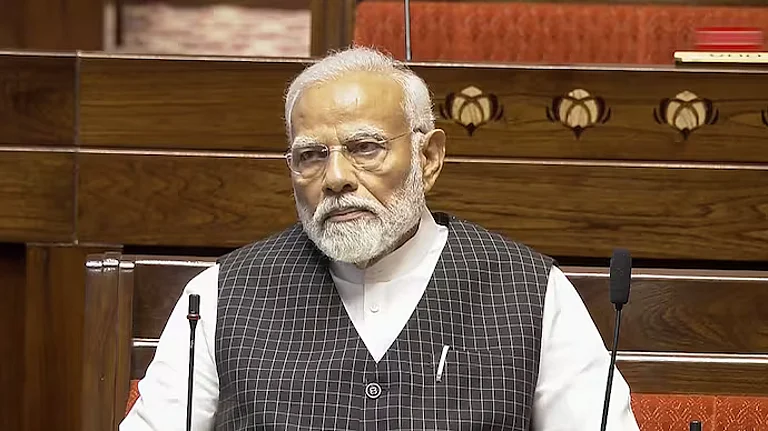

India burned the midnight oil in etching the Global South’s climate finance concerns by seeking to scale up investment and climate finance from billions to trillions of dollars globally from all sources. Furthermore, focused on renewables, G20 under India committed to triple renewable energy capacity globally through existing targets and policies. Finally, India was firm with the developed countries through the G20 New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration to fulfil their ODA commitments and take the lead per the Paris Agreement by undertaking economy-wide absolute emission reduction targets.

UAE’s COP 28 Presidency (2023)

UAE’s COP28, overcrowded by bankers and oil and gas industry lobbyists, found huge relief in India’s G20 language and adopted the outcome of tripling renewable energy capacity globally by 2030. Despite being a petrostate, it committed to pursuing efforts to Transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems, phasing out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, and accelerating zero- and low-emission technologies such as low-carbon hydrogen production, while G20 had referred to the production of zero- and low-emission hydrogen.

Brazil’s G20 Presidency (2024)

While Brazil was balanced in its approach, the Rio Leaders’ Declaration lacked any reference to the word ‘developed countries’. Further, being a Global South leader, it was expected to pursue India’s language on seeking responsibility from the developed countries for their ODA commitments and ensuring their lead by economy-wide absolute emission reduction targets. Further, COP 29 negotiators expected Brazil to provide teeth by reiterating important commitments at COP 28, such as transitioning away from fossil fuels. Instead, G20 under Brazil provided watered-down language and support by stating that G20 fully subscribes to the outcomes of COP28. Fully aware that COP 29 would decide on the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) outcome, G20 pledged blanket support to Baku and neither provided any directions nor aspects to be considered in deciding on the new climate financial package from the developed to the developed world.

Azerbaijan’s COP 29 Presidency (2024)

Climate negotiators arrived at Azerbaijan with limited optimism. A country that earns 90 per cent of its export revenue from oil and gas and is headed by a President who considers them a ‘gift of god’ did not inspire confidence from the inception of Azerbaijan’s COP 29 Presidency. Any success from Baku lay on an NCQG, which, under the Paris Agreement of 2015, calls for a new financial goal to be decided before COP 2025 from a floor of USD 100 billion per year, considering the needs and priorities of developing countries.

However, Baku’s outcome document agreed that the NCQG would be at least USD 300 billion per year by 2035, with developed countries taking the lead in mobilising funds from various sources, public and private, bilateral and multilateral, including alternative sources.

The icing on the cake is encouraging highly debt-vulnerable developing countries to make voluntary contributions, including through South-South cooperation!

Is USD 300 billion a year in Climate Finance Sufficient?

The figure proposed by economists and developing countries was USD 1.3 trillion in climate finance per year, which they received nothing close to. India, which is conservative in its viewpoints, called the adoption of USD 300 billion ‘paltry’ and ‘abysmally poor’ and said that the document’s adoption was ‘stage-managed’. Even this USD 1.3 trillion was never going to be enough since Cornell University’s Cornell Atkinson Centre for Sustainability, in its study, has calculated that just the mitigation requirements add up to about USD 10.5 trillion between now and 2035, of which the developed nations would need to mobilise USD 2.8 trillion from public finance and remaining through private sources.

However, its study has also shown that if developed countries committed to this, they would gain a 2 to 15 times return on their money between USD 5 and USD 41 trillion in just 10 years from mitigation financing.

A Set Back to the Developing World: The Case of India

India, a responsible emerging power with a goal towards a developed nation through Viksit Bharat by 2047, has thus far been cooperative with a reasonable Net Zero 2070 commitment and revised Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) targets with an ambitious 500GW renewable energy capacity target by 2030.

However, despite investing billions in renewable energy, 70 per cent of its energy is still coal-powered, reflecting the complexity of balancing its international commitments and domestic socio-economic challenges. 2024 recorded India’s highest-ever coal import and production. The India growth story is literally power-hungry, and as per Moody’s forecast, our power consumption will rise 46 per cent to 2,524 terawatt hours by 2031.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the growth in developing countries has led to an increased global energy demand of 15 per cent in the last decade. In comparison, 40 per cent of this demand was met through clean energy.

Given this backdrop, India and the rest of the developing world expected realistic climate finance goal support from the developed world at Baku.

India alone needs USD 215 billion over the next seven years to address its climate finance gaps. Further, there are non-trade barriers from the Global North, especially from the European Union, through the Carbon Border Adjustment Tax (CBAM), which taxes certain imported products based on their production process emissions footprint.

Despite the Paris Agreement's attempt to protect developing countries from such response measures and COP28’s firm opposition to unilateral climate change responses that could disguise a restriction on international trade, India and China’s repeated requests to discuss the EU’s climate change-related trade measures were put aside at Baku.

(Sameer Jain is Managing Director, Primus Partners. Views expressed are personal)