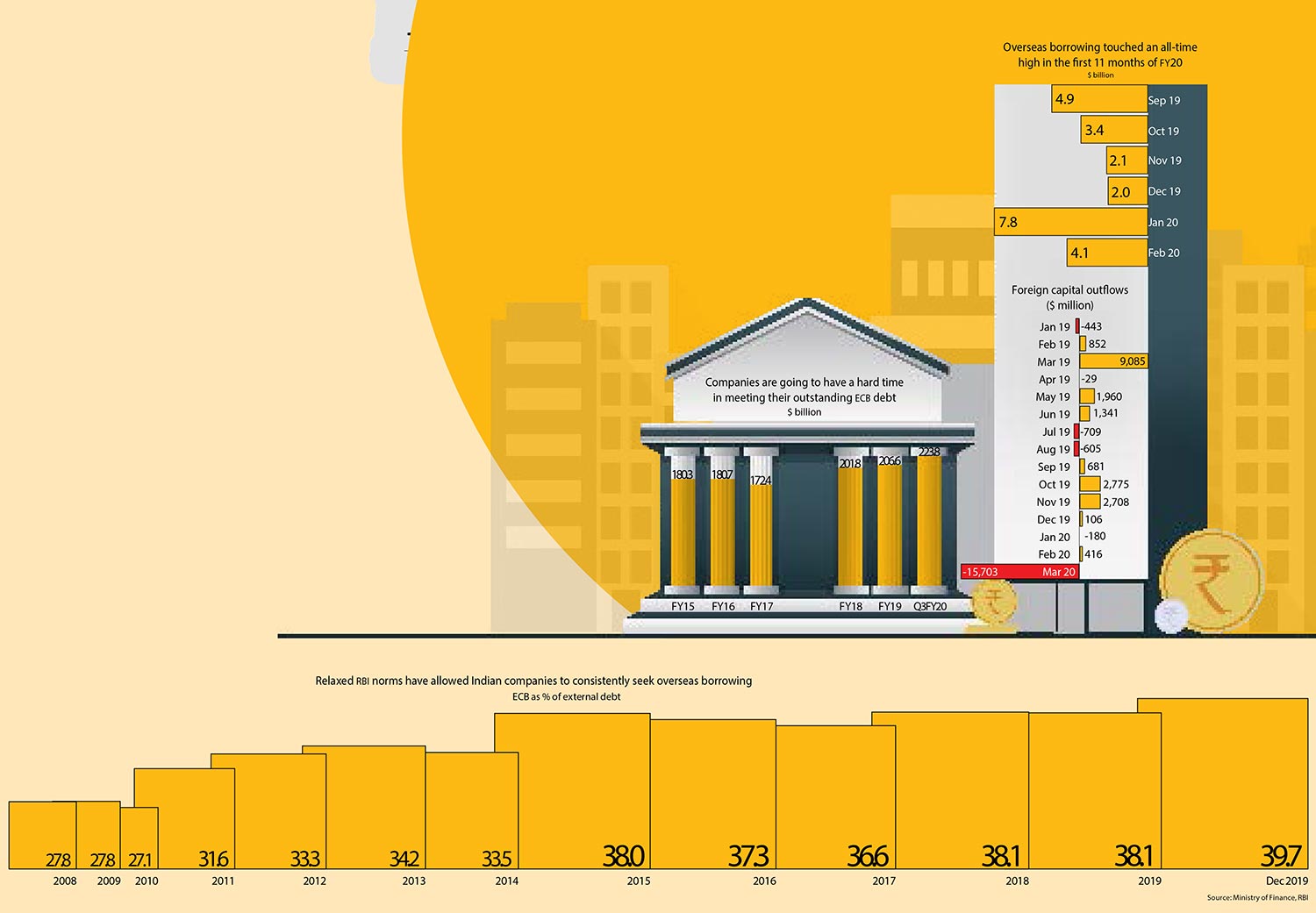

When Don Corleone promises, he delivers. So does the RBI. But, one is a fictional character and the other is the regulator of the Indian banking system. When both delivered, one became a priceless contribution to global cinema and the other bumped up India’s outstanding external commercial borrowing (ECB) by $29 billion to $223.8 billion in December 2019, which alone constitutes 40% of India’s total external debt.

Banking analyst Hemindra Hazari mentions in his report ‘Unhedged Portion of ECBs: One More Threat to Corporate Borrowers?’ that this was triggered by RBI’s move to ease reforms in 2018, amidst a liquidity crunch, especially for NBFCs, and a risk-averse banking industry. Due to government pressure, RBI opened the gates for Indian companies to borrow more in foreign currency. The list of eligible borrowers was expanded and sector-wise borrowing limits were removed; ECBs up to $750 million per financial year were permitted, ceilings on all-in-cost of borrowings were substantially relaxed, and most significantly, mandatory hedging requirement was reduced from 100% to 70%. Essentially, it was an offer Indian corporates could not refuse. Unable to exercise any restrain, they borrowed in foreign currency, enjoying virtually lower interest rate than in the domestic market, and enjoying easier access than from Indian banks. In fact, companies have continued to raise ECBs in the first two months of 2020 as well, with registrations of $7.8 billion in January.

While the data may not have been this alarming until a few months ago, the coronavirus outbreak has turned it into a precarious situation. With COVID-19 breaking the back of the economy, ECBs may turn out to be a nightmare in case of sharp rupee depreciation, something that had not been factored in by Indian companies or even the RBI, states Hazari. Along with a knock-on effect on Indian banks, $34 billion of repayments may be due within the calendar year. But as companies face zero revenue, they may very well not be able to fulfil their debt commitments, leading to default or bankruptcy. This begs us to ask the question, who is whose Godfather?