If you will accept a little oversimplification, the last decade or so of global equity market performance can be summarized as follows. US stocks have profoundly outperformed stocks in the rest of the world, whether other developed markets or emerging markets. This outperformance has been partially driven by US P/E ratios expanding more than in other markets. But the largest driver of the outperformance has been the massive superiority of earnings growth in the US relative to anywhere else. This superior earnings growth has been driven not so much by strong top-line growth, but by expanding profitability by US companies relative to sales, gross profits, or other measures that can plausibly be used as proxies for economic capital. Unlike in past cycles, this rising profitability seems to have been neither a result of, nor a driver of, increased corporate investment. Digging a little deeper, we can see that the improvement in profitability has occurred only in the largest companies. These companies have been out-earning their smaller brethren by increasing margins over the past 25 years or so. The long period of their improvement suggests this effect is not something we should expect to correct over a single business cycle, but my guess is that the world in the future will be less favorable to these large, dominant companies than is true of the current environment.

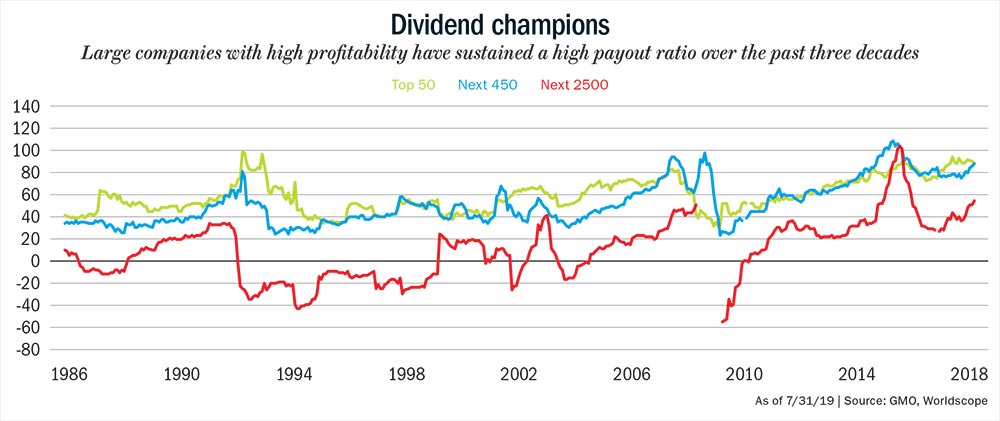

The largest 50 companies have seen a 50% improvement in their adjusted profitability since the earliest decade, while the next 450 have seen a much smaller 24% increase and the rest an 8% decrease. But the gap between the improving fortunes for the largest firms and stagnant fortunes for the bulk of companies does help explain the odd lack of relationship between profits and investment. The largest firms fund their investments more or less entirely out of internal cash flow. The only notable exception to this is when they buy other companies, and that, while certainly an investment from the firm’s standpoint, is not an investment from an overall economic perspective because assets are only shifted around, not created. The companies that do use outside money to make investments are generally small companies. Because the profitability of smaller companies is not particularly high, it cannot be much of a surprise that they feel no burning need to raise capital to ramp up their investments. This still does leave the question as to why the largest firms are not using their enhanced cash flow to increase their own investment rates. After all, if these companies have increased their profits significantly, they could increase their investments out of internally generated cash flow. But the payout ratios of these companies, inclusive of the money they spend on stock buybacks, has instead grown substantially over the past 33 years (See: Dividend champions).

All groups have shown a significant increase in payout. In the case of larger companies, they are now paying out over 70% of their earnings to shareholders. Smaller cap companies pay out much less than their larger counterparts at just over 30% of earnings, but until fairly recently they paid out nothing net of equity issuance, making their shift over the period the largest of any group.

So why would we have a combination of enhanced profitability and decreasing investment? The most plausible answer seems to me to be that increased industry concentration and market power by the largest companies means the bulk of their profits takes the form of economic rents in the businesses in which they are dominant. Because the firms are already dominant in their spaces, there may not be a lot of expanding they can do short of branching out into new business lines, where their position will likely not be as dominant and their profit margins far less enticing.

The investment opportunities of these extraordinary companies do not seem to have grown on pace with the economic rents they are capturing in their current business. And the rest of corporate America is not profitable enough to justify ramping up its investment. What does that tell us about the future of growth and profits in America? The plus side of low rates of investment is that it means less chance of overcapacity, which pushes down profit margins, being created. The minus side is, of course, slow growth. While it is probably unfair to entirely blame the slowdown in US. productivity growth on the fall-off in corporate investment, the period since 2005 has been a uniquely dismal one for productivity growth in the US.

The largest companies presumably quite like the world as it is, given their place in it. While that should not stop them from making investments where they foresee a high return on capital, they have a lot to lose from change and are likely to actively work against disruptive progress. Even apart from a desire to maintain the status quo, dominant companies may well not be in a position to want to aggressively grow for fear of attracting the attention of regulators in the US and abroad. That attention is certainly more clearly focused on the largest technology firms today, although to date the fines and business restrictions placed on them have not put much of a dent in their business models.

As to the question of what this suggests for the future of the US stock market, it’s hard to know for sure, but a few points seem worth making. First, if the shift upward in the profitability of the largest companies has been going on over multiple business cycles, we shouldn’t expect it to unravel the same way that prior cyclical peaks in profitability did. That is not to say that there is not a cyclical element to profitability today, but rather that the cyclical factor looks to be superimposed on another longer-term shift. Our equity forecasts split the difference between assuming profitability is stable over time and that enduring shifts can happen, but they are biased toward an assumption of stability, with two-thirds of the weight on models that assume profitability is stable in the long run.

Because the profitability shift for the largest companies in the US is unprecedented, it’s hard to look back at history to determine how we expect the future should evolve for them. The trend has certainly been in their favor and absent any change in the environment it is tempting to assume things will continue to get better for them. There are a couple of potential flaws in that reasoning. The first is the fact that no company’s competitive position is safe forever. Today’s champions have certainly done well historically – they wouldn’t be the largest companies in the US if they hadn’t done well, after all. But the history of dominant companies shows that their extraordinary profitability tends to decay over time. That decay may be slow or rapid depending on the company. For the most stably dominant companies, such as the ones favored by our Focused Equity team in the GMO Quality Strategy, history suggests that their profitability decays to normal over something like a 30-year period. Now, 30 years is a long time to benefit from above-average profitability, justifying a significant valuation premium over average companies. But from the standpoint of forecasting the future profitability for such companies, it argues for a slow reversion rate for profitability, not no reversion.

But while that might be the right way to think about the largest companies individually, a group of companies needn’t act like an individual company. The largest stocks in the S&P 500 are a different group of companies than they were in 1996, or 2006, and yet their aggregate profitability has risen even as some former stars have seen their fortunes fade. On this front, the question is really whether the environment that has favored these dominant firms is likely to remain so biased in their favor. My guess is that it is not. The recent announcement of anti-trust investigations against the largest technology and related communications firms seems unlikely to be a one-off. Apart from the simple issue of their growing dominance and staggering profits, the negative societal and privacy impacts of their basic business models make it harder to paint them as plucky upstarts improving the world and easier for critics to characterize them as disturbing big brother entities feeding off the worst instincts of humanity. Health care companies face a similarly daunting level of unpopularity, driven by their pricing practices combined with the striking disconnect between the amount the US spends on health care versus the rest of the world and the health outcomes that spending seems to deliver. The growing interest in academia and beyond in studying the deleterious effects of large firms beyond looking at the direct impact on consumer prices also suggests a broader push against dominant firms on principle is increasingly likely.

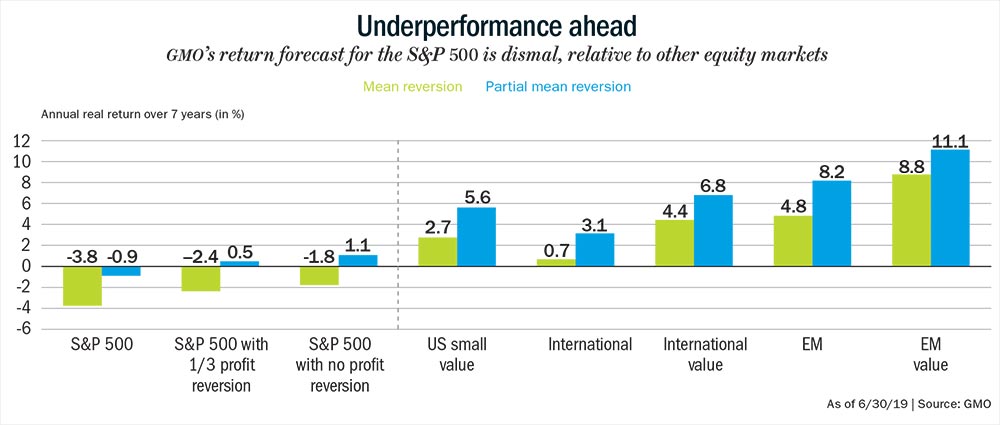

How long these forces will take to play out and how negative they will be for the largest firms is hard to know with any certainty. But it does seem to me that the wiser bet is to assume the world will not remain entirely safe for dominant companies. If we took the stance that the next seven years would see a one-third reversion of the trend of large company margins back to their long-term average, our forecast for the S&P 500 would improve by 1.4%. Given that our current forecast for that group is -3.8% and -0.9% on our two base scenarios, that assumption would raise the forecast to -2.4% and +0.5% (See: Underperformance ahead). That is enough to shrink the US “margin of inferiority” relative to other equities, but still leaves it at the bottom of the equity barrel. Even an assumption that the average profitability did not revert at all would not make a profound difference to the forecast, as it would increase the forecast by about 2%, again not enough to lift it out of the cellar in the equity rankings or to meaningfully change the desired holdings for the portfolios we run.

The groups we are excited about within global equities — US small value, international developed value, and, above all, emerging markets value — are all at least at a 4.5% higher forecast return in the friendliest version of the forecast for the S&P 500, with EM value a stunning 10% to 10.6% higher.

For the moment, we are not making any changes to our “official” asset class forecasts despite a guess that we are being a little tough on the US mega caps. Our preference is to not make one-off adjustments to our forecasts but look for the broader principle behind an issue and find a way to systematically build it into our models. This allows us to test whether a change improves the models across time and region or asset class, as well as making sure that as circumstances change we don’t find ourselves asking every month whether a one-off adjustment is still warranted or should change in magnitude.

But a challenge to our models is an opportunity to improve them, and we are researching the general question of how to tease out cyclical aspects of profitability from potential secular changes. Should we find a method that genuinely seems to improve our understanding of asset class valuations, we will adjust our models accordingly.

— This is an excerpt from Ben Inker’s 2Q2019 Quarterly letter for GMO. You can read the complete version on www.gmo.com