How is the josh? The dialogue from the movie Uri got cult status when prime minister Narendra Modi asked the audience the same question at the inauguration of the National Museum of Indian Cinema in Mumbai early this year. And after the thumping mandate that the BJP got at the hustings, the josh (adrenalin) is running high among foreign portfolio investors (FPIs) as well.

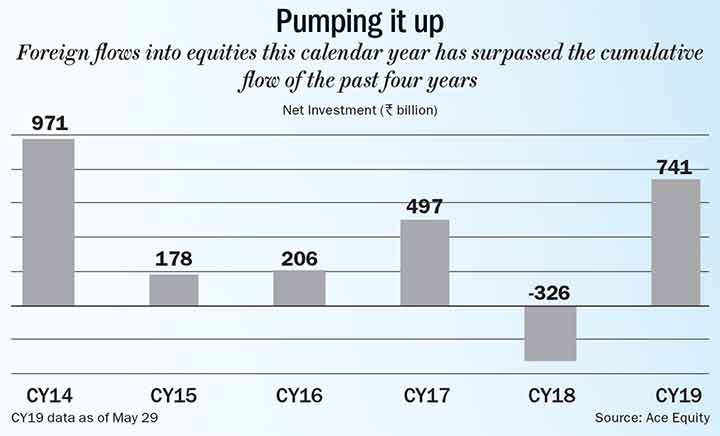

In fact, in just five months of the current calendar year (CY19), FPIs have pumped in a whopping Rs.741 billion into Indian equities after a sell-off saw them pulling out Rs.326 billion in CY18 (See: Pumping it up). What’s interesting to note is that the current year’s flow surpasses cumulative net flows seen over the past four years. The year that the BJP stormed into power (CY14), overseas investors had invested Rs.971 billion.

Putting the rally into context, Mahesh Nandurkar, India strategist at CLSA, says, “What we saw early in the year was a catch-up rally since India was trailing the rest of Asia. In fact, despite the big jump in FII investment in March, Indian market barely caught up with peers. The outperformance only began in May as the verdict came as a huge surprise for foreign investors.”

This year’s Lok Sabha election will go down in India’s history for more reasons than one. It’s the first time that a non-Congress party has come back to power for the second term. It is also the first time since 1984 that a party has captured 300 seats on its own. It was in 1984, after Indira Gandhi’s assassination, that the Rajiv Gandhi-led Congress Party created a record with 404 Lok Sabha seats.

The resounding jump in the indices means investors believe that Modi will continue with his reform initiative. And with a new finance minister in Nirmala Sitharaman, who has handled commerce and defence portfolios in the past, there are huge expectations from North Block as well. With the strong electoral mandate of the incumbent government, demand for stimulus and reforms are also gaining ground. But it’s not going to be a walk in the park for Modi 2.0.

Will He, Won’t He?

While there were questions raised whether the revised GDP series was reflecting the true state of the economy, it continues to indicate that the economy is sputtering. In fact, the day Modi government came back to power, two negative statistics came to the fore. The country’s GDP growth fell to a five-year low of 5.8% in the March quarter, while unemployment rate hit 6.1% as of FY19-end. Though the economic affairs secretary, Subhash Chandra Garg, attributed the slowdown to temporary factors, all eyes will be on how the government cranks up the growth engine.

Gautam Chhaochharia, head of India research, UBS Securities, says, “Over the near term, given Modi’s strong mandate, hopes will be high about the reform narrative. The narrative building on that in the next few weeks merits tracking.”

With 50% of the labour force engaged in agriculture and only 16% of value addition to the economy, job creation would mean that the government has to focus on manufacturing and making the sector more competitive. Manishi Raychaudhuri, head of equity research - Asia Pacific, BNP Paribas Securities, feels law-making could get easier in NDA’s second term. “All new laws need to be passed by both Houses. This means, passing some potentially controversial reforms such as changes to the Land Acquisition Bill could be easier now,” he says. Digitisation of land records, transparency in land transactions, labour reforms to aid hiring, privatisation of PSUs, and consolidation of state-run banks are some of the reforms that BJP can push through.

Currently, the BJP and its allies have 102 seats in the Upper House and would need an additional 21 seats to gain a majority, where the support of 123 is needed to cross the halfway mark. Chhaochharia feels major structural reform on land, labour and privatisation will excite markets, but adds a caveat, “Political capital is higher vis-à-vis 2014, but a majority in the Upper House is unlikely by 2022.”

In the interim, focus should remain on public infrastructure expenditure such as roads, railways, and rural-urban infrastructure. Government spending, which had eased up towards the elections, could see a boost to prevent incremental weakening of demand. But that would entail fiscal and monetary stimulus, both of which are challenging.

According to UBS Securities, policy choices to stimulate growth, such as Goods and Services Tax (GST) rate cut, fiscal stimulus and monetary easing, would also entail rising macro stability risks, rising inflation and higher current account deficit. “Will the new government be fine with those risks ahead of a near-term growth recovery,” asks Chhaochharia.

Managing Money

For now, the consumer price inflation indexis around 2.92%, which is lower than the RBI’s comfort level of 4%. But much of it hinges on food prices and good monsoon. The RBI is expected to reduce repo rate by 50 bps over the next two policy meetings in June and August, factoring in the expected inflation trajectory and growth prospects. But the bigger question is over the transmission of bank rate cuts. Over the past 12 months, the RBI has injected Rs.3.2 trillion through open market operations (OMOs) and about Rs.700 billion through dollar swaps.

Ridham Desai, head of equity research and equity strategist at Morgan Stanley India, believes liquidity will improve as the spending held back during the election season finds its way back into the system. “Taking liquidity to neutral conditions will help ease the tightness that non-banks are suffering from,” says Desai.

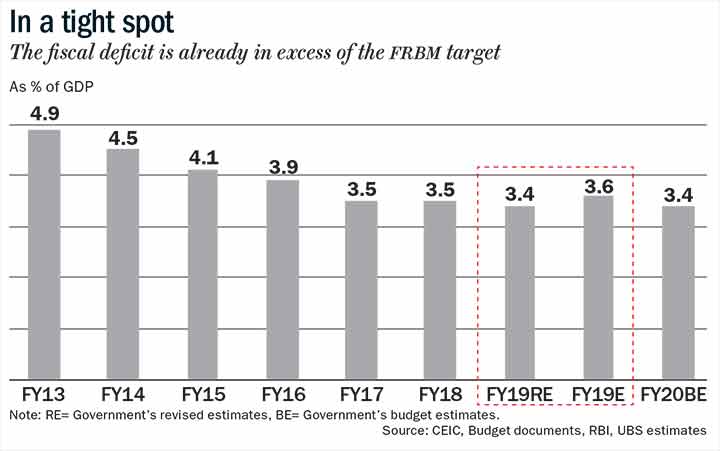

However, given that the government’s consolidated fiscal deficit is around 6% and market borrowings (including PSU borrowings) of around 8%, expanding the fiscal may be counterproductive, states a report by Kotak Institutional Equities (See: In a tight spot). Further, though the total Goods and Services Tax (GST) collection at Rs.1.14 trillion in March was the highest since its introduction in July 2017, the mop-up amount excludes refunds. The Union Budget for FY20 has budgeted a 24% growth in total GST collections, which will be difficult to achieve as the Modi government, in the run-up to the elections, has already slashed tax slabs across several categories.

While higher GST collections are critical, the government would also be looking at disinvestment since it has managed to surpass asset-sale targets of Rs.1 trillion in FY18 and Rs.800 billion in FY19. The target for the current fiscal is pegged at Rs.900 billion, but the shortlist of 24 companies identified for sale, including the ailing Air India and some other loss-making PSUs, may not attract buyers.

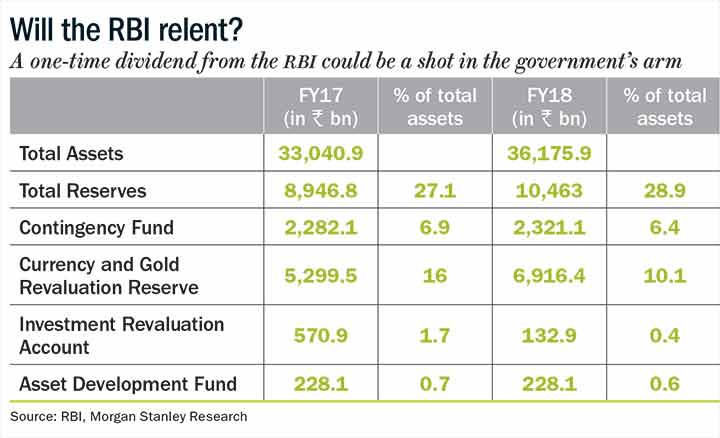

But the big booty that the Modi government wants to lay its hand on is the excess reserves held by the RBI. A committee has been set up, headed by former RBI governor Bimal Jalan, to assess if the central bank is holding excess capital on its balance sheet. As per the Economic Survey, RBI’s total reserves at 28.9% of total assets is at the high-end compared with other global central banks (See: Will the RBI relent?). The debate is — whether the reserves could be potentially transferred to the exchequer as a special dividend. “Potentially, Rs.3.5-4.5 trillion would be the excess reserve on the RBI’s balance sheet,” points out Desai. The excess reserve could be used to recapitalise state-owned banks or retiring public debt, which could give both banks and government leeway to fund growth.

It’s not surprising that the Street believes the government will be able to spur growth, which will help earnings growth.

Increasing Optimism

Earnings growth in India has not been too impressive. And it is clearly evident when Renaissance Investment Managers mentions this in a report, “While Nifty earnings compounded at 13% from Rs.84 in FY98 to Rs.281 in FY08, the following decade earnings compounded at 7% from Rs.247 in FY09 to Rs.496 in FY19.” But UBS Securities believes the narrative around reforms, stable macros and political stability are improving investors’ confidence about India’s long-term growth potential. “This was reflected in multiple re-rating over the past five years, despite muted earnings growth,” points out Chhaochharia.

BNP Paribas Securities had, in June 2018, downgraded India from overweight to neutral on concerns about downward earnings revisions, a possible currency fall amid rising oil price and unjustifiable high premium relative to Asian peers. But Raychaudhuri is turning bullish. “Currency concerns appear to be behind us with recovery in flow, and revival in some macroeconomic variables seem to be paving the way for some degree of earnings stabilisation,” states Raychaudhuri in his report.

Morgan Stanley feels a big improvement in M&A activity could be the precursor to a more robust investment rate, setting the stage for earnings growth. “We think earnings could compound around 20% annually for five years,” says Desai. His conviction comes from the fact that credit growth is at multi-year highs, corporate revenue growth is almost at 20-quarter high and corporate profits are at 25-quarter high.

The long-awaited private capex cycle is likely to turn as the average industrial capacity utilisation has, over the past five quarters, inched up by 7% to reach around 78% in September 2018, close to the levels where companies usually make capacity expansion decisions. CLSA’s Nandurkar says, “A good part of the private investment comprises the housing sector. We have an anti-consensus call since a large chunk of the private investment is the housing market, which we believe, has bottomed out. The housing market revival will be played through cement, housing finance companies and property developers.”

The recent budget saw income tax sops for second-time homebuyers. Besides, the government may look at expanding the scope of the affordable housing scheme (urban) in terms of higher eligible loan amount for interest subvention and/or the interest subvention rate. Around Rs.68 billion was allocated under Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana - Housing for all (PMAY-HFA) urban and Rs.190 billion for HFA rural in the current budget.

Desai of Morgan Stanley points to the other big positive — possibility of a corporate tax cut in the forthcoming budget. “A lower headline rate to 25% for large corporates, as promised by the outgoing finance minister, is a reasonable expectation. A 5% reduction in corporate tax is a 7.5% point boost to earnings, though the effective rate cut could be lower since it may be accompanied by substantial removal of exemptions,” he says.

CLSA believes that with the Nonperforming Loans (NPL) in the system coming off from 11% to 9.5% over the past 12 months, and lower provisioning requirement, banks’ earnings will improve. “Large banks will double their earnings, accompanied by recovery in earnings of property developers,” says Nandurkar.

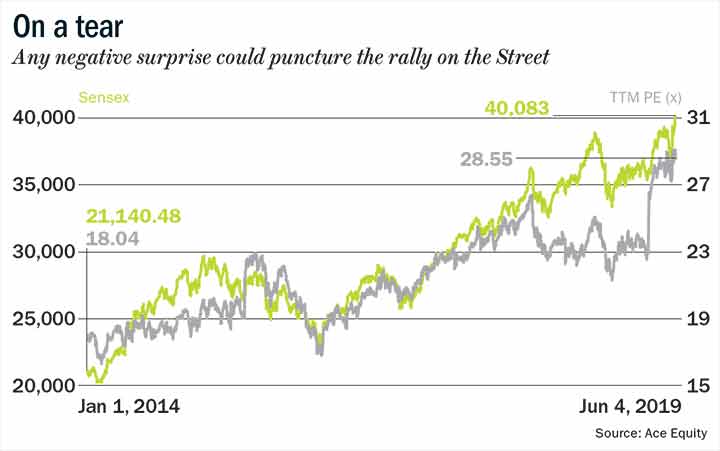

In line with their views, foreign brokerages are looking at a more bullish outcome with UBS looking at a base case of 12,000 for Nifty by December 2019, primarily reflecting a multiple of 18x (See: On a tear). The brokerage has revised its earnings forecasts to 22% and 20% for FY20 and FY21 against 16% and 14% earlier. “If we see the political economy being supportive of near-term growth, then we may see higher earnings growth of 25% and 20%. A multiple of 19x (similar to peak multiples) could lead to an upside scenario of 13,000,” says Chhaochharia.

Morgan Stanley has pegged the Sensex at 45,000 by June 2020, implying that the index will trade at 18.5x one-year forward P/E and 22x on trailing P/E, which is higher than the 25-year trailing average of 19.7x. “We think a multi-year growth cycle is not being priced in, else valuations would be closer to cycle peak. Hence, we see a considerable upside over the next three to five years,” says Desai.

A slowdown in global growth could be tolerated, but profits in India would not be able to withstand a recession, according to Morgan Stanley. Concurring with the view, Nandurkar of CLSA says, “We should not see an escalation in the US-China trade war. Also, a tempering of growth in the US will result in talks of a Fed rate cut, which will be positive. But, US going into recession will be a big negative.”