Hermann Simon, well-known German author and co-founder of Simon-Kucher & Partners, in his 2010 book, Hidden Champions of the 21st Century, has identified not so well-known companies across the globe but which are among the top three players in their respective industries on the global stage. These companies managed to achieve this feat through sharp focus, smart diversification and well-planned market entries across geographies. Ambit Capital, the Mumbai-based independent brokerage house, contextualised the book to identify emerging global champions in the Indian context by using the qualities Simon identified in his book. Nitin Bhasin, head of research at Ambit, who co-authored the report with Nikhil Mathur, besides Anupam Gupta of Aavan Research, shares the idea behind the report and why investors needs to keep an eye on these in-their-own-right giants. Excerpts from an interview:

What led Ambit to adopt Hermann Simon’s book into a research report?

For the past seven years, Ambit has been adapting works of various thinkers into its research. For instance, the accounting thematic report that we come out with was influenced by a book on cash flow accounting by Howard Schilit. Another example is Jim Collins’ Good to Great that inspired us to write notes on ‘great’ Indian companies. Similarly, The Outsiders, which Warren Buffett has spoken quite highly of, inspired us to work on our report titled, Unusual Billionaires. We came across Hidden Champions of the Twenty-First Century little less than a year back. Here was someone talking about small companies becoming champions in their niche businesses. They did so either by increasing their market share globally or by acquiring companies. These companies also chose to diversify, but not into completely unrelated businesses. Simon profiled several small manufacturing companies in his book. Most of these companies focus on a niche product and serve their customers in a manner that differentiates them from the rest.

How did you adapt the book to the Indian context?

Simon’s focus was on manufacturing companies and not service-oriented companies. The companies we have identified in our report might not be exactly in line with Simon’s idea. We had to tweak his criteria to identify Indian names. One of the first criteria for identifying emerging global champions (EGC) is that they should not be well-known. Companies that people know exist, but don’t necessarily know their true potential. Investors need to think what makes a company unique, what the company does differently, how it manages processes and people, even if it is small in size. We are not just picking a company because it aspires to be a meaningful global player — the processes that the company is putting in place today are far more important.

How did you filter out companies while compiling the list?

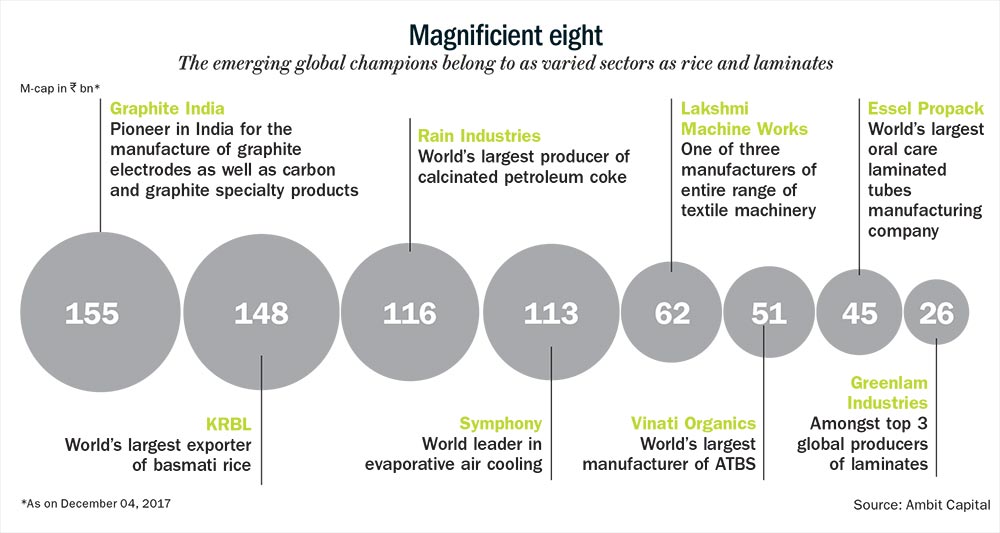

In the first stage, we sorted the top 1,500 companies based on market cap since we wanted to avoid too small or too big a company. We then excluded the top 100 and for the remaining 1,400 ,we looked at companies with revenue less than $4 billion. Next, we focused on companies selling abroad or had just started selling recently, but, more importantly, aspired to be a meaningful player in its space globally. The company could be looking to achieve this organically by increasing exports or inorganically by acquiring assets abroad. Later, we applied subjective filters to examine the credibility of a company’s accounts. Did the company have a credible management or do we know something about this company that made it unworthy of investors’ trust? Again here, we only filtered out companies where we had strong opinions. For instance, not many understand Rain Industries or KRBL, for that matter. There are not many reports on these companies. Also, we didn’t have any strong negative opinion on their accounts or on their promoters. So, we ended up including them in our EGC list.

So, what led you to the final shortlist?

Take the case of Greenlam Industries. Globally, there are only one or two players trying to sell branded laminates such as Wilsonart and Formica. Even though Greenlam is a fraction of the size of Wilsonart, it meets the criteria as it is the world’s third-largest producer of laminates. Importantly, it is focusing on building its brand, building the market and setting up the business for the next 10 years. The company could possibly become a credible No 2 over the years. Many companies from India make laminates and export it to distributors or manufacture for OEMs. Some 20 years back, Greenlam was one of them — manufacturing for OEMs. The company changed tack and chose to create its own brand in each market and build a team in each of those markets irrespective of the size of the business — whether it was $10 million or $20 million. The teams went out and engaged with contractors, architects, interior designers and apprised them of the product, the design, services standards, and kept in sync with emerging trends. After all, laminate is a fashion product. Ask anybody in the laminates industry which is the most professionally-run company, the answer will be Greenlam. This is despite the fact that the company is not the big daddy given its topline is just #1,000 crore, with 60-70% sales coming from India. But how it is going about its business is impressive. A visit to Greenlam’s stall at Acetech [leading trade fair in Asia for architecture and building materials], will give a sense of how different it is from the rest. The company is there just for the branding, and not for pushing its products. That makes a huge difference. Besides, they are also hiring professionals from different industries. A well-known tiles player twice the size of Greenlam told us that they look up to Greenlam’s product innovation and aspire to reach similar standards. It is still early days for Greenlam in India and it is difficult to say whether they will succeed but they have got futuristic products in doors and floorings space. This is a company where it can’t innovate much in terms of the product, but the way they are approaching the global market is very different compared to what other players tend to do. Asian Paints, too, went abroad, so did Berger Paints, but they have not cracked it. Greenlam is yet to make a profit in its overseas businesses, but it is getting better. They have reduced losses in certain markets abroad.

Why did a rice producer like KRBL make the cut?

KRBL also fits into the contours of an emerging global champion. It exports basmati rice to Middle-East and to certain states in North America. KRBL is a pretty big player in India and by exporting its branded products, it is becoming a meaning ful player globally.

Isn’t consumption of basmati rice largely restricted to the Indian diaspora?

If you look at the Middle-East, they consume a lot of rice. Africa could also be a very big consumer of rice. Wherever there is rice consumption, Indian companies have a market there and certain Indian players are making the most of these opportunities. Globally, bread is more popular than rice. However, we are also seeing rising consumption of Pilaf [a dish in which rice is cooked in a seasoned broth]. KRBL is focused on a niche product and is trying to offer it in a way that differentiates it from others.

What innovation are we seeing in a commodity such as basmati rice?

Innovation doesn’t necessarily have to revolve around R&D, it could mean doing things differently. The kind of people the company hires, the kind of machinery the company uses, the branding strategy that it adopts and also what unique processes does it follow. In the case of KRBL, innovation can also be seen in its farmer engagement programme. KRBL maintains its own farms to identify the kind of seeds it should be developing for better yields even if there is not enough water. Although it has not entered into contract farming, working with farmers has helped create a strong ecosystem. On the distribution side, it has entered modern trade. It is building a portfolio of multiple brands of rice with different positioning. The KRBL story is not widely known with hardly any institutional investor presence. The whole sector was stereotyped as most rice players ran their businesses in a shoddy manner. KRBL changed the perception. Look at its return on capital employed versus the industry, it clearly stands out. Look at its branding practices versus the industry, it’s different. This is in spite of the fact that KRBL’s product may not be the most expensive compared with peers, but it is more profitable among its peers. KRBL has complete control on its production process — right from power, raw materials to the farmer. At the same time, it is focusing on making the balance-sheet better. The story for KRBL began when it developed a seed with better productivity — the rice that came out from the seed was of a superior quality and found wider acceptance. But the company did not just engage merely in product innovation, but innovated its processes as well.

Any other Emerging Global Champion which has taken innovation beyond products?

Another case in point is Symphony. The company took its understanding of managing an ecosystem of vendors, suppliers and manufacturing to turn around businesses it acquired in Mexico and North America. This is the same company which had gone bankrupt in 2002-2003 by trying to do too many things besides coolers. That’s when the management chose to focus just on coolers and outsource manufacturing. The promoter put more emphasis on branding and designing. In India, it was successful as a room cooler company. But, globally, room cooler is not a very big product. So, Symphony acquired a company in Mexico and turned it around in three years. They could do it because they got the right kind of people and incentivised them properly. The company showed them that you don’t have to necessarily manufacture everything. One needs to build an ecosystem of suppliers and be frugal with one’s own resources.

Why does Lakshmi Machine Works feature in the list?

Till two-three decades back, LMW was a partner with Rieter, a globally-recognised name in spinning machines. Today, LMW is respected by every Indian spinning company, possibly at par with Rieter. Customers pay LMW money in advance; an indication of the standing it has created. Globally, spinning is a niche industry. Barring the Chinese, Rieter and LMW are the only two players. Only recently, LMW started exporting out of India. Even though the market might be weak right now, channel checks suggest that almost all spinning companies in the developed markets know of LMW. They don’t mind buying from LMW instead of Rieter if the former is giving them earlier delivery. LMW as a brand may not be quite popular among the general public, but a company buy a spinning machine is well aware of LMW. Thanks to its historical relationships with Rieter, LMW has also improved its technology over the years. Unlike other EGC where export markets can be very large, LMW may not be that sort of player. This is because spinning is only one leg of the entire textile manufacturing process. Also LMW suffers from one weakness – it is dependent on a niche market which is not very large. But you never know, a high-engineering company can diversify into other industries. We have been hearing that LMW is working towards understanding aerospace and defence.

Can such a diversification not backfire?

All of these EGCs are attempting some diversification where the downside is limited. LMW, for example, is trying to make components. Manufacturing a component entails designing it, lathe work and precision cutting, similar to what is needed in a mega-spinning machine. That is why focus is very important. For example, Hero has got into so many sectors, right from housing finance, two-wheeler finance to energy. You need to focus to become a global giant and your diversification has to be around your core. A company which is making elevators today, might tomorrow say, I am going to make escalators. This is still a related diversification. Tomorrow, they may say we want to get into most of the mobility solutions in a building; let’s say cranes. Essel Propack, which also features in our list, is now diversifying into non-oral care categories. However, they are still sticking to the core of packaging. They are not getting into a completely unrelated business such as pipe manufacturing. Essentially, the idea is to look for companies which want to play the global game in a focused manner.

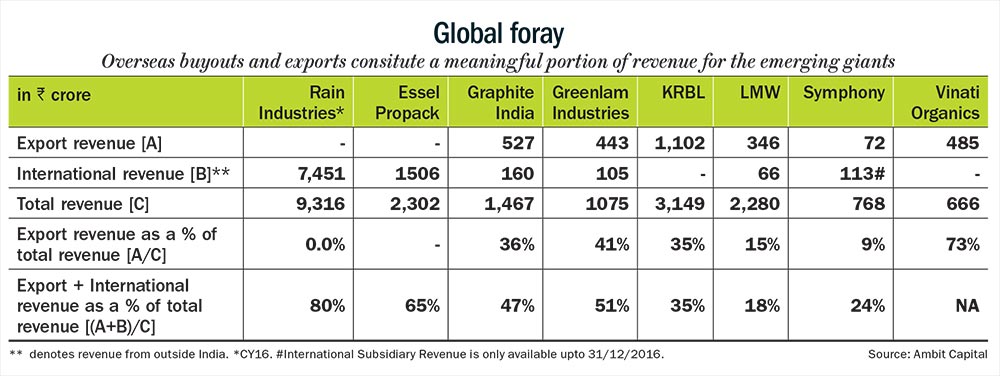

How much did exports or acquisitions matter while shortlisting these companies?

Exports will always be important for these companies. It may be 15%-20% today and in certain cases it will be zero. For instance, Symphony doesn’t have any exports. But it has a business in China and Mexico. So, it can incorporate a company there to sell its products. It might help Symphony become a global air-cooling brand. It is a similar case with Motherson Sumi which is today India’s most successful story. They don’t export anything from India. They have actually acquired companies abroad to become a global champion in the ancillary space. The times of only manufacturing and exporting out of the country are gone — every company that wants to become a global champion cannot say that my capital allocation will only be in India. India is no more offering you the best talent in engineering or the best logistics. Globally, there may be assets available in smaller niche opportunities which local players may not want to own, but certain Indian players could run it. Take the case of Suprajit Engineering, which makes cable wires. Then it did a diversification in India by acquiring Phoenix Lamps which also had an international business. They understood cable wires for two-wheelers and three-wheelers and then they acquired a company in the US which manufactured cable wires for non-automotive purposes. Auto ancillary and engineering companies have done that historically; they have gone abroad and acquired. The question is whether you want to acquire balance-sheet heavy businesses similar to Hindalco-Novelis, Tata Steel-Corus, or whether you want to build a network of niches.

Are these companies looking for inorganic opportunities because they are finding it difficult to sustain growth organically?

While there is a motherhood statement that most acquisitions don’t play out, it is also important to understand why they don’t play out. Firstly, acquisitions should be done at reasonable valuations and, secondly, the promoter has to be hands-on, but still delegate responsibilities. Companies that have built their businesses by acquiring teams have done a great job. If it works right, you get an asset at a cheap value, you get market entry and you get an exceptional team. If an acquisition doesn’t string all those three things together then there is a challenge. So, I think small Indian promoters who are focused, hands-on and are also building teams will use acquisitions to build their businesses.

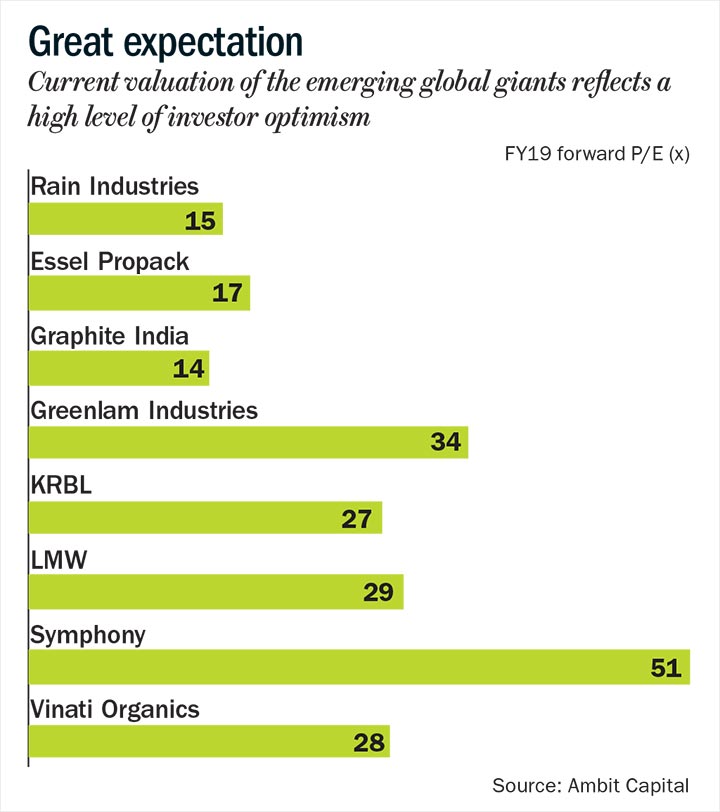

Some of the EGCs that you have identified like Graphite India and Rain Industries are in commodity-linked businesses which are cyclical, isn’t that a risk?

Being in a commodity business is not necessarily a problem. Look at Shree Cement. Even though they are in a commoditised business, see the kind of wealth they have generated. It is the lowest-cost cement producer. For 50 years, nobody in India could make money in the airline business, but IndiGo managed to make money. AIA Engineering, which makes grinding media for metals and mining and cement sectors, is a proven global champion. AIA is telling companies to use its superior quality products rather than poor quality products which are cheaper. If tomorrow China decides to shut down 15%-20% of its capacity, there will be a natural demand for Graphite India’s products and the story could sustain for the next 5-7 years. If in the meantime, they are also able to improve their balance sheet, they can make a bigger bet for the next cycle. By acquiring assets overseas, Rain Industries has built a position of dominance in a niche business. If electric vehicles gain traction, aluminium demand will go up. Rain Industries, which produces calcined petroleum coke and coal tar pitch used in extraction of aluminium, can see improved demand as a result.

What makes Vinati Organics an emerging giant?

Not many companies call themselves specialty chemical companies with a focus on R&D and product development. Right from the early 90s, Vinati always partnered with institutes to develop a greener and a cost-efficient methodology to produce chemicals. They are also able to gain significant market share as they are able to reduce costs and also devise a cleaner way of producing chemicals. Whenever they start to think about making a product, they think how they can make it greener and cleaner. Everybody else focuses on how they can make it cheaper. Vinati is able to offer a sustainable product to its customers. Everyone is trying to play the environmental arbitrage, but Vinati Organics doesn’t want the arbitrage to be their key selling point (i.e. producing cheaper products as there is no strict requirement for environmental compliance) as they will get exposed in a matter of time. Over the past couple of months, players such as Aarti Industries have started winning projects for long-dated contracts globally because for the past three years they have started focusing on health, safety and environment. Vinati also has a different approach. Instead of making many products, Vinati makes only 2 or 3 products and tries to dominate those markets after getting its processes right. Their business might seem commoditised, but when you look closely they are real product innovators.

What are some of the risks associated with these EGCs?

All these companies run a keyman risk — whether it is Saurabh Mittal of Greenlam or the Mittal and Gupta families at KRBL or Vinod Saraf planning R&D at Vinati, or Achal Bakeri at Symphony who is taking a call on the company’s capital allocation. It also means that the promoters need to be extremely focused. Besides, keyman dependence, capital allocation is another risk. There will be times when these companies will have to borrow, there will be opportunities when they would want to acquire, or situations where they will be required to pull back from certain markets which are not working. If these companies throw good money after bad, it could be a cause for worry.