The country is reeling under a liquidity crisis and you know it’s not getting any better when the central bank goes all out to ease liquidity – the RBI recently lowered the repo rate by a quizzical 35 basis points. While the transmission of lower rates to borrowers is in question, the June quarter performance of lenders has been better than other sectors. “Net interest income (NII) of 10 BFSI companies (Nifty constituents) grew by 14.3% YoY, whereas net profit grew by 149.9%,” states a Centrum Research report. A low base effect, clean-up of balance sheets and recapitalisation by the government has led to this outperformance.

Naturally, mutual funds and investors have turned overweight on the sector. But the dismal growth in core sectors (electricity, steel, refinery products, crude oil, coal, cement, natural gas and fertilisers) and an ongoing slowdown in the economy could still play spoilsport. The bad loan cycle seems to have peaked, but the further economic slowdown may lead to a new round of defaults in the banking sector.

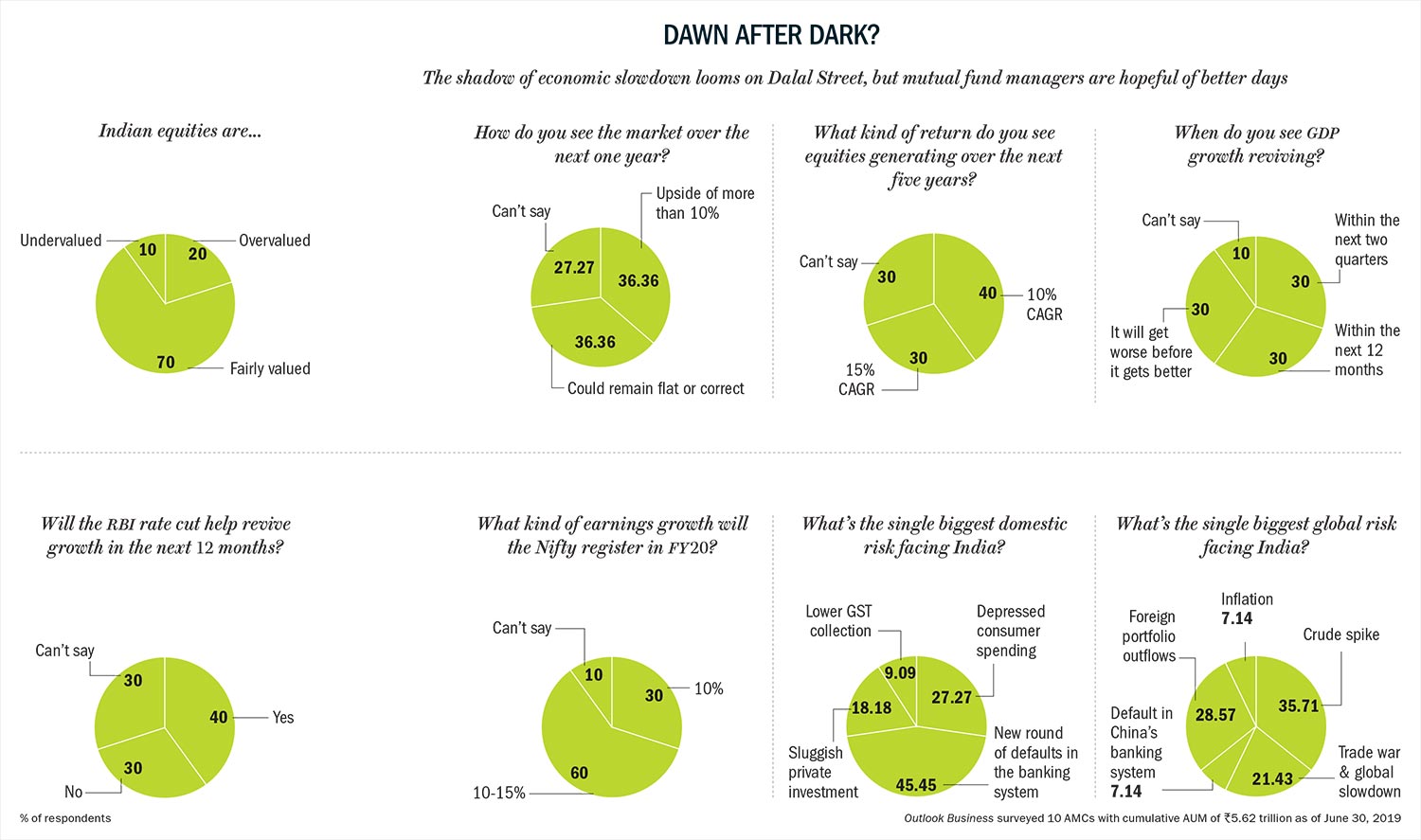

And to understand the mood of the market, Outlook Business conducted a survey in the last week of August (See: Dawn after dark?). What we found was that a fresh wave of bad loans is the single biggest domestic risk according to 45% of mutual fund managers.

“If new and chunky bad loans emerge, it can be risky for banks’ earnings growth and overall markets,” says Pankaj Tibrewal, equity portfolio manager and senior VP, Kotak Mutual Fund. New NPAs could in fact hamper banks’ ability to lend and could hurt small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and large corporates.

“Over the past nine months, NPAs have risen following the IL&FS default. No one was able to predict this. My biggest fear is that a fresh set of bad loans can cool down the whole economy,” says Vinit Sambre, head of equities, DSP Investment Managers.

Consumption conundrum

If bad loans are the scary monster under the bed, then consumption slowdown is the poltergeist that refuses to vanish, creating havoc every now and then. That’s another headache for investors right now, as India’s Primary Consumer Index dropped by 3.1% in August, weighed down by high cost of living, weak economic growth and shortage of funds for spending and investment. One of the most visible signs of this slowdown is falling passenger vehicle sales over the past one year. At the same time, fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) sales remain subdued.

When the economy goes through challenging times, consumer demand weakens, observes Jinesh Gopani, head of equity, Axis Mutual Fund. It’s a vicious cycle. “Around 70% of our GDP is driven by consumption, so it makes India a consumption-led economy. If it slows down, then the Indian economy will slow down,” adds Gopani.

So, what will it take for the economy to bounce back to its glory days and halt the slowdown? Will the rate cuts by the RBI act as an enabler? The mutual fund community is split over the impact of the central bank’s ability to spur economic growth, but they all agree that merely reducing rates won’t be enough.

Akash Singhania, fund manager, Motilal Oswal Mutual Fund asserts that rate cuts alone won’t sufficiently push demand. “Growth and demand are dependent on a lot of factors. Demand is driven by job creation, capital formation, income growth and purchasing power, affordable pricing,” he says. Union Mutual Fund’s CIO Vinay Paharia concurs. He believes spending power has to increase if we want revival in consumer sentiment. “If the consumers don’t wish to spend and their incomes are not growing, then they would not be encouraged to spend more. It would force them to save, which won’t lead to improvement in economic activity,” says Paharia.

While fall in income could be detrimental for economic growth, growing unemployment is also a significant hurdle. Around half of the mutual fund managers see it as the most significant challenge confronting the government. In May 2019, the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) revealed that India’s unemployment rate was at 45-year high of 6.1%.

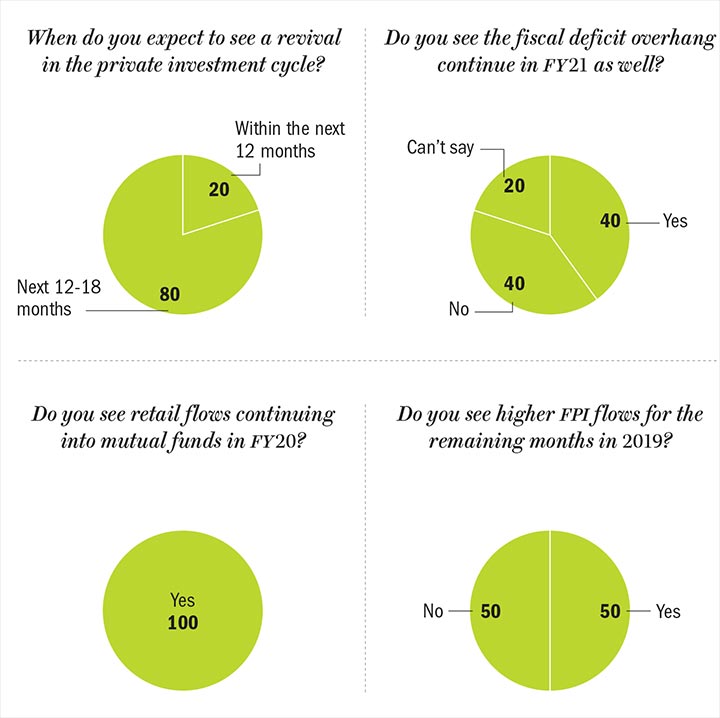

That’s not all. Besides weak consumer sentiment and dismal job creation, the long awaited pick-up in private capex is still nowhere in sight. None of the mutual fund managers predicted that private investment would accelerate in the next two quarters. The hope is of a pickup over the next 12-18 months. Capacity utilisation in sectors such as cement and steel is expected to peak out by then and kick in a fresh cycle.

With private players shying away from capital expenditure, the government is running out of options to meet its FY20 fiscal deficit target of 3.4%. It will have to strike a delicate balance, states Paharia adding that it cannot afford to cut expenditure, as economic growth is subdued. This means, the hangover of the deficit will cast its shadow over the next financial year, too. Hence, the pain is likely to continue.

Global woes

Speaking of pain, the one global hurdle that has been a topic of discussion for the past few years is – the volatile crude price. With Brent trading at $60/barrel, any spike could have a cascading effect on the current and fiscal account. It has the potential to upset fiscal math and eat into earnings of sectors such as airlines, paints, logistics, tyres, luggage, oil refinery and marketing companies and many more. It can also spark fear of inflation and skew the pitch for more rate cuts. With India being the third largest importer of crude oil, mutual fund managers deem it as the biggest global risk facing India followed by foreign portfolio outflows and trade wars.

“We have been dependent of imported oil, which impacts our overall current account deficit and valuation of our currency,” says Tibrewal. Meanwhile, foreign portfolio investors (FPIs) have not been too happy about India’s slowing GDP growth. “This impacts our equity market directly and indirectly. FPIs are holding corporate bonds too. So, if there is an outflow in the bond market, then it can hurt the currency and indirectly, the stock market,” opines Tibrewal.

But India is not alone. The economies of biggies are also weakening. There’s a saying that goes – If the US sneezes, then the world catches a cold. Add China to that, and you get the current global picture. Today, the Asian powerhouse is the fastest growing economy in the world, and along with Uncle Sam, accounts for 41.7% of global GDP. Such is their financial clout that the talk of a no-holds-barred trade war between them is roiling markets worldwide.

Like the rest of the world, ramification of the escalating trade war will be felt in India as well. Our exports will be hit if global slowdown continues, and for a country that has been trying to boost just that, the trade tiff between the two giants is bad news. Sambre says, “The trade war will be a trigger for a global slowdown as it’s contagious.” Singhania of Motilal Oswal Mutual Fund also recounts that whenever there has been a global slowdown, earnings have come under pressure. “Global trade war and the resultant slowdown are the biggest risks, and it’s very concerning,” adds Singhania.

Opportunity in crisis

The government’s stance has not helped either. Post the announcement of Union Budget, the market has sharply corrected. The slapping of a higher tax surcharge on FPIs has hurt investor sentiment besides weak earnings growth in Q1FY20. Despite the surcharge rollback by the government, the road ahead remains bumpy. The volatility is expected to continue, as a cocktail of global and domestic headwind loom over the market, even with the dip in valuation. A market that was perceived expensive earlier, is now termed as fairly valued, according to 70% of fund managers in our survey. With the broader market attractively valued, investors will get better return in the next 12-18 months, predict some fund managers.

Gopani prefers large-caps as adverse macro conditions are not conducive for small and mid-caps. “However, we also believe that opportunities have emerged in small and mid-caps, too, post the steep correction. Companies with well-defined niche and strong moat are likely to deliver above-average return,” claims Gopani.

Concerns over new potential defaults in the banking system remain, but most fund managers are optimistic about the prospects of lenders going forward. Gopani says he’s impressed with banks’ growth rate and their ability to manage asset quality. Within the financial space, Sambre prefers private banks since public sector banks remain saddled with higher NPAs. He believes only those who haven’t got caught in the tangle of poor asset quality will be able to gain market share in the coming future.

Industrials, especially engineering and capital goods companies, have emerged as the second favourite amongst mutual funds. Although meaningful recovery in private investment remains elusive, fresh order flows are expected to end the cyclical downturn in the upcoming months, which will be triggered by an increase in capacity utilisation.

While the fund managers interviewed in this survey stand divided over the near term prospects, they are confident that India’s long-term growth story remains intact. But investors will have to sail through choppy watersfor now, before reaching the promised land of higher growth and favourable macro.

Just one email a week

Just one email a week