For 57-year-old Seema Dhawan using a BluSmart cab was a conscious decision. “I run an NGO by the name The Roadsides for clean and green roadsides. Using BluSmart went with my ethos,” she says. But Dhawan will have to slow down on her efforts to lessen fossil-fuel pollution.

Out of the blue in April this year the all-electric ride-hailing service hit the brakes and suspended service. Barely 24 months ago, India’s urban mobility sector was riding a green wave. Four-year old BluSmart was gearing up to challenge Ola and Uber with a bold promise: clean, affordable and reliable commutes.

With BluSmart’s 5,000-strong electric-vehicle (EV) fleet already zipping across Delhi-NCR and Bengaluru by January 2023, and ambitious plans to scale to 1 lakh cars by 2025, it seemed like the EV revolution was knocking on the door for India’s ride-hailing services.

The timing couldn’t have been better. Public sentiment was turning against legacy players over inconsistent service while regulators were getting restless over pollution from petrol and diesel fleets. BluSmart’s entry infused fresh energy into the market.

The same year (2023), Ola announced its EV plans while Uber rolled out Uber Green and signed a massive EV deal with Tata Motors. Suddenly, the electrification of Indian ride-hailing didn’t just seem possible, it seemed inevitable.

Caution Ahead

But behind all this buzz, a more sobering reality was beginning to emerge. Drivers were struggling with long charging times, battery issues and higher operating costs. Above all, the government subsidies that had sweetened the EV deal were vanishing for electric four-wheelers. And by early 2025, the early momentum seemed to fizzle as quickly as it had ignited.

While the unravelling of BluSmart over the past few months dealt a blow to the sector, industry experts say there are bigger problems in the electric-fleet economy that need urgent attention from all the stakeholders: governments, original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), financiers and ride-hailing platforms.

The tall EV targets set by ride-hailing platforms in 2023 largely fell short. By January 2025, BluSmart had a fleet of just 8,600 EVs, well below the 14,000 figure it planned by 2024. Uber, despite its large network of 4 lakh vehicles, had only about 6,000 EVs, according to media reports. Ola fared the worst, putting its electric-car plans on the back burner altogether.

Ola declined to comment on its EV targets while Uber did not share the EV fleet size on its platform. BluSmart could not be reached for comments.

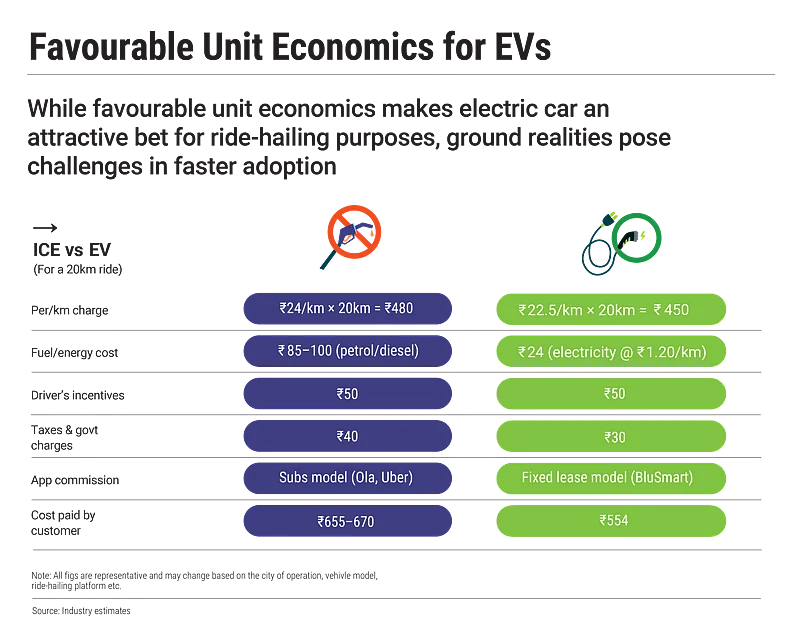

Electric ride-hailing had promised a cheaper and cleaner alternative to internal combustion engine (ICE) cabs. But the road ahead turned out to be potholed. Despite lower per-km fuel costs, total operating expenses for EV fleets remain high.

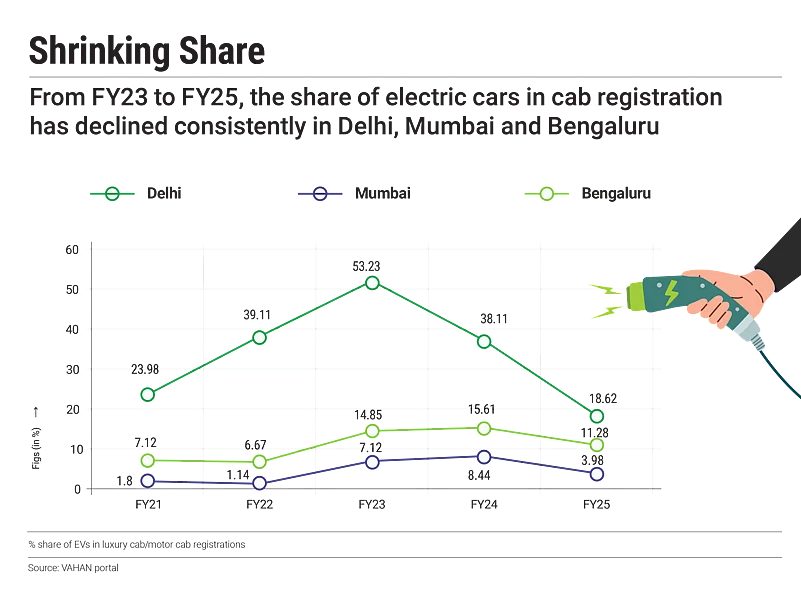

These operational hurdles started to pop up in registration trends as well. According to data from the government’s VAHAN portal, the share of EVs in taxi registrations in Delhi plummeted from 53.2% in 2022–23 to 18.6% in 2024–25. Of the 6,015 taxis registered in 2022–23, 3,202 were EVs. That number plummeted to just 888 out of 4,768 in 2024–25.

Similar trends were observed in Mumbai (from 7.1% in 2022–23 to 3.9% in 2024–25) and Bengaluru (from 14.9% to 11.3%).

No More Carrots

According to analysts, one major reason behind the slowdown in adoption is the high upfront cost of EVs, worsened by the absence of targeted incentives for electric four-wheelers under the Centre’s PM E-DRIVE scheme.

The expiry of the FAME II scheme in March 2024 marked a significant turning point for the electric cab and taxi segment. Under FAME II, electric four-wheelers for commercial use were eligible for demand incentives of ₹10,000 per kilowatt-hour (kWh) of battery capacity, capped at ₹1.5 lakh per vehicle. This subsidy applied only to vehicles priced under ₹15 lakh (ex-factory) and was primarily targeted at fleet operators.

In addition, FAME II supported the rollout of public charging infrastructure in urban areas and allowed operators to benefit from state-level incentives such as road-tax waivers and registration-fee exemptions. Together, these measures reduced the total cost of ownership and helped make electric cabs financially viable.

Once the scheme ended, vehicle prices rose by ₹1–1.5 lakh, weakening the business case for EV adoption, says Nikhil Dhaka, vice-president at Primus Partners, a management consultancy.

In October 2024, the government replaced FAME II with the ₹10,900 crore PM E-DRIVE scheme. It prioritised the deployment of electric two-wheelers and three-wheelers and supported the purchase of over 14,000 electric buses but moved away from providing direct support for electric four-wheelers.

For the cab segment, the absence of targeted four-wheeler incentives was a setback. According to Dhaka, such incentives were crucial for cab operators to absorb the high upfront cost of switching to electric. As a result, many operators chose to hold back on investment or return to ICE vehicles.

Speed Breakers

Beyond just costs, EVs bring their own set of challenges on the road. Unlike ICE vehicles that can refuel in minutes, EVs take 45–60 minutes to recharge even at DC fast-charging stations. Fast charging, though quicker, accelerates battery wear and reduces its lifespan. “Longer charging time directly reduces the number of daily trips—impacting earnings for those already working on tight margins,” says Pratip Mazumder, India country manager, inDrive, a ride-hailing service.

Compounding the issue is reduced battery warranty for commercial users. Many EV manufacturers offer shorter or conditional battery coverage for commercial use compared to personal use. Although lithium-ion battery prices have fallen from around $150/kWh to about $100/kWh, the battery remains the most expensive component of an EV. Ironically, the high-utilisation rates that are key to early return on investment for drivers end up becoming a liability due to faster battery degradation.

Drivers also face environmental challenges. Many told Outlook Business that hot weather and heavy rains can interfere with EV performance. “The battery sometimes disconnects while charging,” says a former BluSmart driver. According to a study published in the February issue of Applied Energy, energy use in an electric car increases by 25–28% as temperatures rise from 26–30°C to 46–50°C while the driving range decreases by 16%.

These unresolved issues make one thing clear: ride-hailing companies are still grappling with the fundamental challenge of building a sustainable EV business model. BluSmart, for instance, initially stood out by addressing driver grievances and customer dissatisfaction plaguing Ola and Uber. However, its asset-heavy model—owning the cars and infrastructure—led to high cash burn.

In the Red

“For running a commercial EV fleet there are very high fixed costs because EVs require constant charging. You need real estate for parking, you need energy, you need people to handle all this, further increasing the overall cost of ownership and operation. A lot of that fixed cost is not there for ICE,” argues Kunal Khattar, founding partner at AdvantEdge Founders, a venture-capital firm.

This high capex took a toll on the company’s financials. BluSmart has remained in the red since its launch in 2019, reporting a net loss of ₹215 crore in 2022–23, more than double the ₹100 crore loss in 2021–22, according to Tracxn, a data firm.

On the other hand, asset-light players like Ola and Uber relied on driver-owned vehicles, making EV adoption largely dependent on individual drivers.

According to Redseer Strategy Consultants, net earnings per cab in a driver-owned-vehicle model are 20–30% higher for EV cabs when compared to petrol cabs depending on cab utilisation. But drivers seemed reluctant to make the switch as the difference in earnings reduces significantly in the case of comparison with CNG for EVs.

“Drivers have experienced extreme highs and lows in earnings over the years. They hesitate to invest in EVs that come with higher EMI costs,” says Rohan Agarwal, partner at Redseer.

EV manufacturers and financiers also lagged in innovation and developing models to specifically cater to the needs of the ride-hailing industry, experts say. While OEMs designed vehicles for personal use, shared-mobility operators employed them for commercial use where the utilisation of the vehicle rapidly reduced its performance.

“The current vehicle options being used by fleets have been designed for personal mobility, which means they’re supposed to be driven 50–60km a day and slow charged every night at home. Unfortunately, nobody in India has yet built the right EV at the right price point for ride sharing,” Khattar says.

Forging New Paths

In a market where the unit economics of EVs remain challenging, financiers are crafting more flexible solutions for gig workers. These include low down payments, pay-per-km EMIs and customisable loan tenures. With traditional lenders still wary of emerging EV technologies, non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) are collaborating with EV manufacturers to offer bundled packages that include the vehicle, financing, insurance and maintenance services.

“Charging partnerships and support for battery-swapping ecosystems are helping drivers increase their earnings,” says Dhiraj Agrawal, chief business officer, Mufin Green Finance, a green NBFC.

India’s ride-hailing market is poised for strong growth—expected to expand from close to $951mn in 2023–24 to $3.7bn-plus by 2031–32, at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 18.78%, according to research firm Markets and Data. With electric passenger vehicle sales surging by 58% in April to over 12,300 units, industry experts believe these gains will eventually extend to the ride-hailing segment as well.

“The EV transition was never going to happen overnight. It was always meant to be a slow, steady shift—but ending ICE Age is inevitable,” says Khattar.