In Nandita Das’s 2022 film Zwigato, the protagonist Manas, played by stand-up comic Kapil Sharma, a former factory floor manager-turned-food delivery executive, says at one point, “I used to manage 200 people on the factory floor. But this app will kill me.” The character’s journey echoes the life of Kartik Gautam, a gig worker in Delhi.

Twenty-eight-year-old Gautam works two jobs, both in India’s booming gig economy. Mornings, he spends delivering food. Evenings, he turns his bike into a bike-taxi and takes irate passengers returning from work back home through the capital’s congested streets. All this effort earns him around Rs 22,000 a month, after accounting for fuel costs.

Gautam moved from Meerut, Uttar Pradesh to Delhi two years ago. He is among the millions on whom it depends if India will ever realise its demographic dividend. But he is tired, anxious, unhappy and craves a semblance of financial and social security.

A sense of security that is unlikely to be his, at least in the near term. Primarily because Gautam works his gigs with million-dollar food-delivery or ride-hailing firms who don’t think of him as their ‘employee’. They prefer ‘partner’ instead.

Not because they think of Gautam as an equal. But because calling him an ‘employee’ would require them to pay for his provident fund, health insurance and incur other costs that employers are required to by law.

Devil in the Definition

A Niti Aayog report published in 2022 estimated that India had nearly 7.7mn gig workers in 2021. The report, titled India’s Booming Gig and Platform Economy, projected that the number of gig workers in India may rise to 23.5mn by 2030. A government source, speaking on condition of anonymity, tells Outlook Business that the current number of gig workers may be around 20mn.

That is roughly around the population of Sweden, Denmark and Finland put together. All these millions are ‘partners’ of multi-million-dollar firms and thus are not eligible for social-security benefits typically due to formal employees. These millions have been forced to take up gig work at a time when the Indian economy has struggled to create enough formal jobs.

Out of a population of 1.4bn, less than half (545mn) were part of the labour force in 2023, according to the International Labour Organisation (ILO). Of these, only 10% had formal jobs.

What About Business?

But why don’t companies treat gig workers as employees and offer them social-security benefits? Essentially because the business model of platforms depends on it. Many of these businesses sustain singularly because they are able to circumvent labour-related legislation.

“For most companies in this segment, their competitiveness arises from their ability to evade taxes and disregard statutory provisions on minimum wages and other benefits,” according to a paper by MMK Sardana titled Formalising the Indian Economy on the Wings of Demonetisation, GST and Technology published by the Institute for Studies in Industrial Development (ISID). The paper argues, “Lacking in technology and scale, this is the only way companies are able to compete with large, organised players.”

Most big platform-based companies have made losses in the past few years. Food-delivery giant Swiggy, for example, reported a loss of Rs 2,350.24 crore in financial year 2024. The company had reported a loss of Rs 4,179.3 crore in financial year 2023 and Rs 3,628.9 crore in financial year 2022. Its main competitor Zomato reported a consolidated profit of Rs 351 crore in 2024 after reporting losses of Rs 971 crore in 2023 and Rs 1,222.5 crore in 2022.

Making these businesses pay for the social security of gig workers will not only raise costs for the explicit purpose of social security but also increase cost of compliance, says Akshay Jain, partner at law firm Saraf and Partners. “This will also require increased worker engagement, including mechanisms to address grievances raised by workers regarding potential errors,” he adds.

Solution on the Horizon

Millions of young people without social security are bound to make any government anxious. The Narendra Modi government is no exception. Especially at a time when it is feeling cornered for not being able to create enough jobs.

“One of the reasons the Modi government suffered a setback in the recent [Lok Sabha] elections was the sentiment around weak jobs growth,” says Trinh Nguyen, a senior economist focused on Asia at the Hong Kong-based investment banking company Natixis.

Jobs in the gig economy have possibly offset some of the anger that could have poured into the streets without them. Of that, the government seems aware. “The gig workforce, primarily consisting of the poor and the underprivileged, must not have their rights overlooked,” says Union Labour Minister Mansukh Mandaviya.

The first step in bringing gig workers under the ambit of social-security policies was taken in 2020 with the introduction of the Code on Social Security. This was the first piece of legislation recognising gig workers. It also laid the groundwork for social-security provisions.

Among social security provisions, the Centre is mulling bringing gig and platform workers under the Employees’ Pension Scheme (EPS), a scheme that for now applies to formal workers. Under the scheme, an employee contributes 12% of their basic salary to their pension account, and their employer matches the contribution. The government also contributes.

Problem with the Solution

While the Union government feels that formalising gig workers is the only way to provide social security to them, it is easier said than done. Mostly because the gig economy comprises not only platform-based workers but also contractual labour. Thus making it difficult to get an estimate of the size of the gig workforce.

The Union labour ministry has been trying to deal with this challenge through the e-Shram portal launched in 2021. The ministry has advised employers across sectors to register on the portal to identify gig workers and extend to them social-security schemes. This would in turn help formalise the workforce, the government seems to think.

But experts say that success of such an initiative would hinge on ensuring that the benefits reach the most marginal members of the gig workforce. “Given that gig workers operate on a flexible model and come from different states, it will be time-consuming for aggregators to collect comprehensive information about each worker,” says Manmeet Kaur, partner at Karanjawala & Co, a business-law firm.

Kaur adds that aggregators will need to ensure that details such as date of joining and exit are accurately updated on the portal. “This exercise could be both resource-intensive and challenging due to the frequent movement and switching of gig workers,” she says.

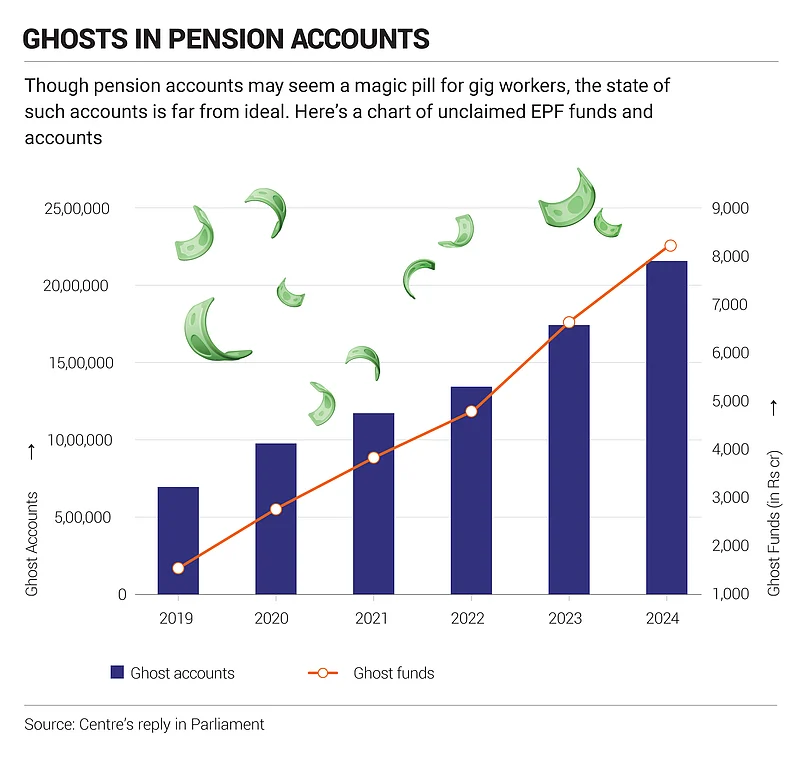

Her note of caution is reinforced by the systemic challenges in formal employment schemes, such as the rapid increase in the number of inoperative employee provident fund (EPF) accounts, which reflects the difficulty of ensuring that benefits reach eligible workers—whether due to a lack of awareness or flexible work models.

The total amount of money in inoperative EPF accounts has jumped five-fold from Rs 1,638 crore in financial year 2019 to Rs 8,505 crore in 2024. Union Minister of State for Labour and Employment Shobha Karandlaje says, “All such inoperative accounts have definite claimants and whenever such a member files a claim in the EPFO, the same is settled after scrutiny.” She further says the government is taking several steps to raise awareness and improve the use of the funds.

There’s No Magic Pill

The code on gig workers, however, is yet to be enforced. Karandlaje recently told the Lok Sabha that five states and Union Territories are yet to publish the draft rules under the code.

One of the things holding up the implementation of the code and inclusion of gig workers under EPS is confusion and controversy around the employer’s share. Since the relationship between gig workers and platforms is not the typical employer-employee relationship and further because many gig workers work with multiple platforms.

“A potential solution being explored is the concept of portable benefits where multiple platforms contribute to a worker’s social security,” says a senior official of the Union labour ministry. The official, speaking on condition of anonymity, explains, “If a worker is engaged with three platforms, each would pay a small portion of the worker’s earnings into their pension funds ensuring coverage without deduction from worker’s salary.”

But for portable benefits to succeed, the government must establish and oversee a system of portable social-security benefits, says Sanjay Chadha, director of public policy for India and South Asia at Uber. “This would involve registering all gig workers, collecting contributions from platforms and ensuring these funds are used equitably for their social security,” adds Chadha, who is also the chairperson of the Public Affairs Forum of India (PAFI) Gig Economy Council.

Other efforts to bring gig workers into the social security net are also lying in wait. Rajasthan, in 2023, became the first state to introduce a gig worker-related law called the Rajasthan Platform-Based Gig Workers (Registration and Welfare) Act. But a change of guard in December has stalled its progress.

In Karnataka, the state’s legislative assembly has tabled a bill called the Karnataka Platform-Based Gig Workers (Social Security and Welfare) Bill. The stated aim of the bill is to protect the rights of platform-based gig workers and impose obligations on online platforms and aggregators concerning social security and occupational health and safety. That Bill is yet to be passed.

Meanwhile, the Leftovers

In the 2024 Malayalam film Baaki Vannavar (The Leftovers), the protagonist is a young man with a master’s degree in economics. He is desperately looking for a formal job as he sustains himself on his income from working in an imaginary food-delivery platform called ‘Eamato’.

At a poignant moment in the film, the protagonist sits by as two people, around the same age as him, argue angrily about the state of the nation. One of them asks the other: “Tell me one thing that’s not there in this country.” The other replies: “There are no jobs that justify my qualification.” The protagonist looks away.

India’s ascendence as a developed nation depends on how its young people feel now and in the years to come, when the demographic dividend will gradually begin to fade. How these millions of gig workers feel about the economy will in many ways determine how India feels about itself.

For now, there is not enough good news on that front. A large young population in the current economic climate is a double-edged sword. While a working, skilled, educated workforce can propel a nation’s economic growth, an anxious, desperate youth bulge can tear the social fabric asunder. Policymakers, companies and governments at the Union and state need to get their act together.