A quiet but unmistakable shift is emerging in fintech venture-capital (VC) circles—defined by a fatigue with lending pitches and a growing interest in segments such as wealth management and stockbroking.

Take, for instance, Arjun Malhotra, general partner at the early-stage VC firm Good Capital. In recent years, Malhotra has made it a point to avoid the lending space. “I stay away from lending completely,” he says, adding that most pitches he’s se-en over the past four to five years are built around regulatory gaps or loopholes rather than sustainable businesses.

He admits to turning down most of the pitches before even stepping into a meeting room. The thrill, he says, just isn’t there anymore. “If the momentum in lending hasn’t already slowed,” he notes, “it’s only a matter of time before it does.”

Acts I and II

The first phase of Indian fintech, catalysed by demonetisation in 2016, saw explosive growth in digital payments. First, there was the unified payments interface (UPI) success story, with payment platforms investing billions of dollars to ride the wave.

According to the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), UPI transactions skyrocketed from 12.5bn in the financial year 2020 to 186bn in the financial year 2025.

Despite this scale, UPI never turned into a revenue-generating opportunity. The reason was the government’s merchant discount rate (MDR) policy under which merchants were no longer charged for accepting UPI payments. While this helped digital adoption and drive volume, it choked a vital revenue stream for payments platforms.

Without MDR income, many wallet companies struggled to sustain cashbacks and incentives that were once key to user acquisition and retention. Eventually, UPI became an unsustainable model—barring a few well-funded players like Google’s GPay and Walmart-backed PhonePe.

The second wave was that of digital lending. As unsecured personal loans surged after the pandemic, concerns began to mount at RBI. Regulatory tightening had started around 2020, but a full-blown crackdown followed in 2021 after rising consumer complaints and incidents linked to predatory lending apps. The concern that the unbridled growth of unsecured loans could endanger the stability of the financial sector was the final straw.

The regulatory shift that followed—making digital lending costlier for online platforms—led to the collapse of several buy now, pay later (BNPL) start-ups. Fintechs believe the impact went far beyond compliance. It undermined investor confidence and forced companies to pivot or pause business lines overnight. “We had to freeze entire operations because of the regulatory flux. No one wants to build on moving ground,” says one founder.

New Opportunities

As regulation squeezes fintechs at both ends—free infrastructure in payments and high capital risk in lending—founders point out that this model is fundamentally broken and leaves little room for innovation, let alone profitability.

Compared to payments, where margins are razor thin, and lending, which is harder to scale and the unit economics equally strained, wealth and broking platforms operate on a more sustainable model once established. In this context, the newer platforms seemingly strike a rare balance—better margins and lower regulatory heat—as yet.

Paytm, PhonePe, and most recently digital-payment platform MobiKwik have entered the stock-broking arena. In March, Mobikwik, announced plans to expand into stockbroking and trade in shares, bonds, commodities, currencies and their derivatives. The company also plans to become a full-fledged stock and commodity broker by registering on stock exchanges in India and abroad.

The digital-wealth sector in India follows two business models. One is the broking model, where platforms earn based on how often and how much users trade. In this setup, every time a user places a trade, the platform charges a small fee. The model has become especially popular in the fast-growing futures and options (F&O) segment.

Then there is the online wealth-management model that focuses on long-term investing and financial planning. These platforms earn advisory commissions or trailing fees from mutual funds.

Compared to payments, where margins are razor thin, and lending, which is harder to scale, wealth and broking platforms operate on a more sustainable model. The newer platforms strike a rare balance—better margins and lower regulatory heat—as yet

Experts point out that the most exciting opportunity in wealth management lies in the mass-affluent segment, that is, individuals who have significant savings but not enough to qualify for private banking services. “People in the 30–40 age group were lacking guidance in managing their wealth. That’s when I decided to use technology to scale and reach out to more people,” says Anand K Rathi, cofounder, Mira Money, an investment platform.

These businesses require initial capital to build the platform, acquire licences and attract users, but once they have built a solid customer base, they typically don’t need ongoing infusions of capital.

Unlike digital lenders, they’re not constantly deploying large amounts of money as loans. Instead, once the platform is up and running, it can start becoming profitable, as revenue is generated through user transactions, advisory fees or investment commissions.

“Furthermore, regulators have eased licensing and many broking licences are available in the market. Some fintechs, like Slice, have even picked up stakes in banks to access licences,” says Vivek Belgavi, fintech partner at professional-services firm PricewaterhouseCoopers.

So Far, So Good

The shift has been a long time coming as newer platforms gain momentum. Overall funding in the brokerage and wealth-management space has grown over the past decade, from $190.8mn in 2016 to a peak of $714.8mn in 2021, driven largely by increased investor interest in brokerage startups, according to data platform Tracxn.

Although funding levels dipped in the following years, the sector has shown signs of recovery—reaching $266.7mn in 2024.

At present, only a handful of fintech start-ups have a lending component, while “the rest are in other areas like investments, savings, enterprise fintech”, says Siddharth Pai, founding partner, 3one4 Capital, a VC firm.

While digitisation of services and streamlined know-your-customer (KYC) processes have made financial products more accessible, a couple of factors have accelerated growth. Since the pandemic, India’s internet user base has grown. Along with it, the number of demat accounts have increased from 55mn in financial year 2021 to 151mn in financial year 2024, shows data from National Securities Depository and Central Depository Services.

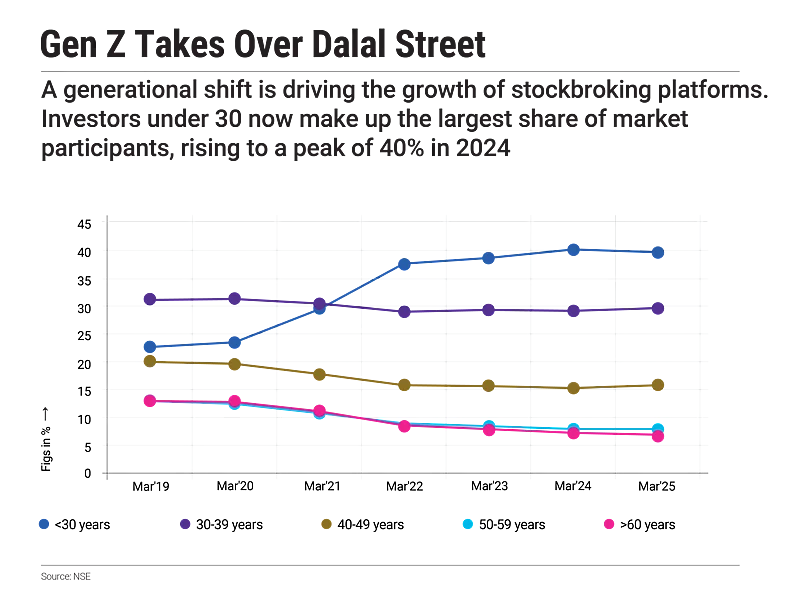

A generational shift is also driving the numbers. Broking platforms have seen an explosion in retail participation, especially among younger users. Online trading platforms like Zerodha, Groww and Upstox have benefitted from this shift, while heavyweight payments players like Paytm, PhonePe and MobiKwik have also entered the stock-broking arena.

The space is also drawing serial entrepreneurs and seasoned unicorn executives who see untapped potential in the market. Dale Vaz, former chief technology officer at online food ordering and delivery company Swiggy, launched Sahi in 2024, a stock-trading platform aimed at young investors.

Around the same time, former senior executives at financial-services company Navi, Shobhit Agarwal and Apurv Anand, ventured into the asset-management space with a new firm focused on retail investors.

Ujjwal Jain, chief executive of PhonePe’s broking platform Share.Market, points to the increase in share of savings flowing into equities, indicating the rapid growth of a diverse trading community and the hard truth that equity investing is no longer niche; it’s gone mainstream.

New Risks Loom

In financial year 2024, Zerodha reported a net profit of ₹4,700 crore, a 62% increase over the previous year. Later the same year, chief executive Nithin Kamath, in a blogpost, reiterated his reluctance to go public, citing the unpredictability of the broking business.

Pointing out that he had often been asked why the company had not gone public, he explained that an initial public offering (IPO) would not have been a conclusion, but rather the beginning of a new phase.

Kamath emphasised that when retail investors become part of ownership, a company should be able to offer a baseline of revenue predictability, something he had not been able to accurately predict since the company’s inception.

This perspective also aligns with recent market trends. The Sensex peaked at an all-time high of 85,978.25 in late September 2024 but has since declined, falling to around 79,454 by May 2025.

Since the pandemic, India's internet user base has grown. Along with it, the number of demat accounts have increased from 55mn in FY21 to 151mn in FY24

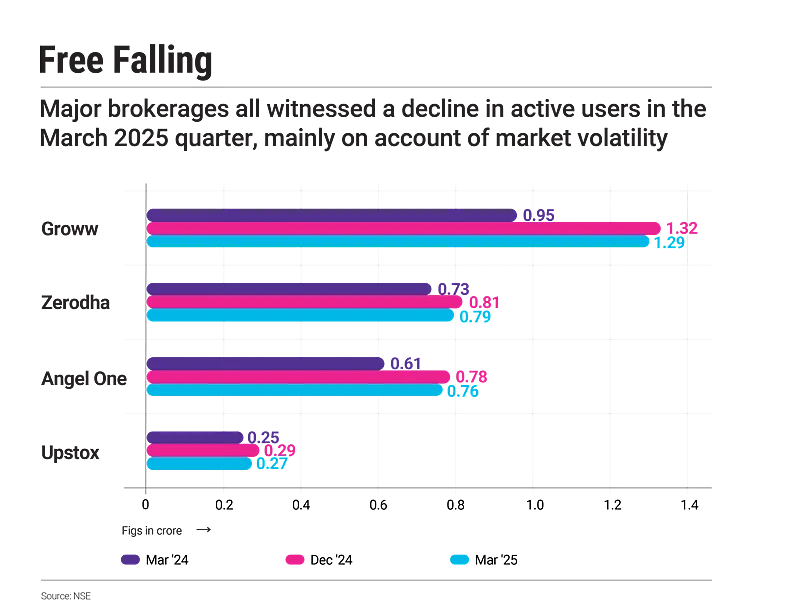

Adding to the pressure, NSE data reveals that March 2025 marked the second consecutive quarter of declining active users for India’s top four digital brokerages. Groww lost 2.37 lakh investors in the March quarter, declining from 1.32 crore users in December 2024 to 1.29 crore, while Angel One and Zerodha saw declines of 1.76 lakh and 2.33 lakh clients, respectively.

Further, a big shift today is market regulator Sebi's move to make rules in the F&O segment more stringent with the aim to curtail retail investor participation and protect their financial well-being. As this is the most lucrative segment for brokers, the move is likely to have a negative impact on their earnings.

And it’s not just this one rule. In August 2024, Sebi introduced the Cybersecurity and Cyber Resilience Framework to strengthen digital defences across regulated entities—including mutual funds, investment advisers and portfolio managers.

The framework has drawn criticism from fintech start-ups and smaller financial players, who argue that applying the same stringent cybersecurity norms to everyone places a disproportionate compliance burden on smaller firms.

“From our perspective, being regulated is not a pain at all. That said, the regulatory environment in India is not the best—it is painful,” says Rohit Beri, chief executive and chief information officer of investment company ArthAlpha.

The problem, say many founders, isn’t with the intent of regulation—it’s the timing and execution. Too often, rules are introduced only after start-ups have raised capital, hired teams, and scaled, forcing abrupt pivots or rollbacks.

As India rides the third wave of fintech, the sector faces twin headwinds: regulatory overhang and uncertain markets. Whether it can navigate these challenges or falters under their weight remains the question. What’s clear is that success now depends not just on innovation, but on how policy and market forces align—or collide.

(with inputs from Tarunya Sanjay)