Something odd happened to me the other night. My cellphone rang at 2 am, from a number I didn’t recognise. I let it go to voicemail, because there was no one I knew in Washington state that had a good reason to speak to me at that hour. I was not put out that the phone had rung in the middle of the night — I had to get up anyway so I could take our new puppy out for her nighttime walk. When I woke up the next morning, I was somewhat surprised to see that the caller left voicemail, which I of course listened to. To be honest, it consisted mostly of expletives, but as near as I could tell the caller is quite angry with me for having suggested that retail investors would be left holding the bag when the market falls. I will admit to feeling a bit honoured to be considered consequential enough to be a focus of some random person’s wrath, even if I’m a little confused as to why he singled me out as I hadn’t meant to pick on retail in the way he implied. So, to clarify to whomever it is that I offended by implying that retail investors might be left holding the bag when a speculative bubble bursts, the reason I mentioned retail investors is not because they are uniquely likely to lose money in the bursting of a speculative bubble. Lots of people and entities lose money when speculative bubbles burst. I mentioned retail investors because they are generally the only people who lose money in the bursting of a speculative bubble who are deserving of much sympathy. As the Archegos saga showed a few weeks ago, both sophisticated institutional investors and sophisticated financial institutions are more than capable of losing large sums of money when their speculative bets go bad. It’s just extremely hard to feel bad for them when it happens.

But the event did seem like a nice excuse for me to write a piece on the distinction between investment and speculation and why the stock market is probably a particularly dangerous place to tread when speculative activity starts to overwhelm investing activity.

Much investing activity contains an element of speculation, and it is hard to imagine the functioning of an equity market in which speculation was entirely absent. Despite that, speculation and investment are, to my mind, quite distinct activities economically. While there are a number of reasonable definitions one could give for these activities, over the years, I have found it useful to think in terms of the following for them:

Investment: The deployment of capital to perform an economic service for which a rational counterparty should be willing to pay.

Speculation: The deployment of capital to achieve an expected gain based on an investor’s prediction of how future prices will differ from the market’s expectations.

Investment as an activity allows for both parties to do a transaction and be satisfied with the outcome, whereas speculation generally implies a winner and a loser. The trouble with investing as an activity is that it is generally pretty boring. The expected returns that are consistent with your counterparty also being satisfied with the outcome are necessarily moderate unless your counterparty was in severe distress when you made the investment. You are unlikely to get rich quick from investment activities, even if your longterm results should be satisfactory. Speculation, on the other hand, offers the potential for large and/or quick gains if you predict things well. Furthermore, it offers the prospect of the psychological reward of both “winning” the transaction and having been proven right.

Speculative bubble

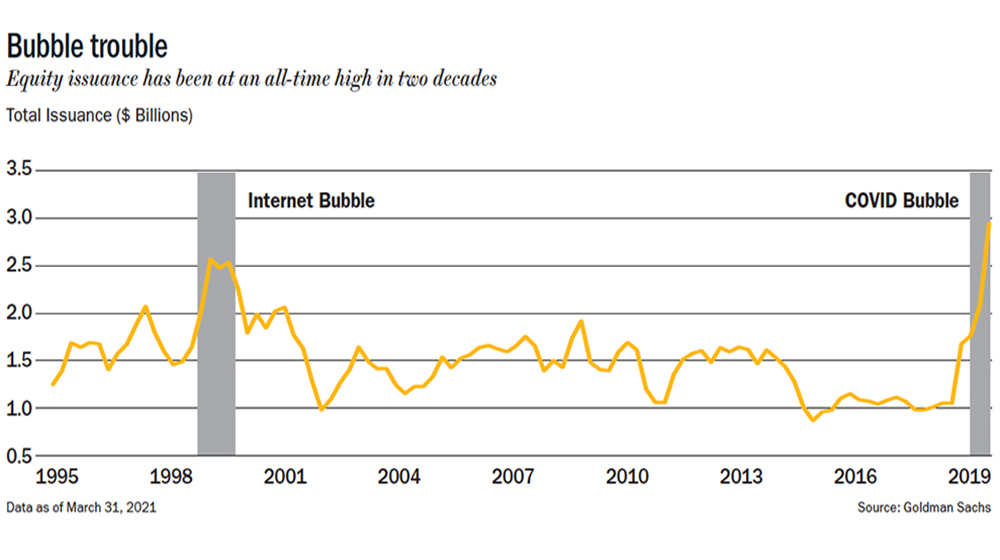

The stock market has always been good at delivering what investors are craving, and there is nothing like a speculative bubble to get the issuance flowing (See: Bubble trouble).

Issuance doubled as a per cent of the us GDP at the height of the internet bubble, but the recent burst has been even more impressive. Not only has the last year seen the highest level of issuance since the data I’m using began, it did so from what had been desultory levels over the previous half decade.

Issuance doubled as a per cent of the us GDP at the height of the internet bubble, but the recent burst has been even more impressive. Not only has the last year seen the highest level of issuance since the data I’m using began, it did so from what had been desultory levels over the previous half decade.

The US stock market of 2017-2019 may well have been quite expensive relative to history, but it didn’t show many of the other classic symptoms of a speculative bubble. That has now changed. As striking as this burst of issuance is, I’d argue that the form of the issuance this time is particularly laser-focused on giving speculators what they are hunger for. SPACs, among their other interesting features, give their promoters the ability to create more of whatever type of stock is coveted in the market with impressive speed. And while it is easy to say that the burst in SPAC issuance in recent months is unprecedented, lots of things are unprecedented. Today’s activity surely deserves some grander term (See: SPAC-ed out?).

The last 12 months have seen 2.5x the total issuance of SPACS in all of history up until then. The first quarter of 2021 itself exceeded those 25 years by about 50%! While there is a fair bit to be concerned about when it comes to SPACs, the issue with them from the standpoint of the sustainability of today’s speculative frenzy is that they are both exceedingly agile and impressively large. EVs fall out of favour and artificially intelligent robotic personal assistants become the next passion for investors? No worries. As long as some companies somewhere are at work on that problem, enterprising SPAC managers can bring a perceived solution to investors. Whether those companies have actually succeeded in building a prototype or even figured out the use case for it is a relatively minor issue as long as the SPAC can get the deal to market before fashions change.

The fact that issuance went up in the internet bubble certainly isn’t enough to prove that issuance is a problem in a speculative bubble. To even come close to proving that we’d need a case study where two or more equivalent speculative booms either had or did not have a burst of issuance occur.

So I will admit my argument about issuance being a problem for a speculative bubble is mostly a theoretical one. But I was able to find one event that seemed like a reasonable test case, even if it wasn’t in the stock market. In the mid-2000s, house prices boomed in a number of different countries in the developed world. According to data from the BIS, 12 different countries in the developed world experienced house price increases of at least 50% in real terms between 2001 and their peak prior to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008. As near as I can tell, this event was the only such global house price boom on record, as housing markets are much less globally correlated than stock markets. These housing booms differed in the scale of the national price increase, the valuation of house prices versus household incomes at their peaks, and the extent to which the price boom engendered a boom in the supply of houses as well. They also differed in the size of the price fall from the peak to the post-GFC low. The data I could find from the period, as well as the correlation of each of the characteristics of the boom with the subsequent fall in house prices (See: Boom and bust).

The scale of the housing boom was not a good predictor of the subsequent bust, with a correlation of only -4%. This is probably not too much of a surprise because different markets started at quite different valuations for housing in 2001. Peak housing “valuations” in the form of price/income levels did a much better job of predicting the subsequent falls, with a correlation of -51%. But the best predictor of the subsequent fall in prices was the increase in housing supply, with a correlation of -69%. Correlation, famously, does not prove causality, but the data for the 2000s’ housing boom is certainly consistent with increased supply eventually putting pressure on prices, with supply being as big a problem as valuations in a speculative boom.

But beyond the supply impact on demand imbalances, there is also a more direct way that the increase in capital raised can create problems for a highly priced stock market. Expensive stocks can wind up justifying their prices when the underlying companies can generate both strong growth and a high return on capital over time. But throwing more capital at an area creates more competition for a given niche, and more competitive industries almost invariably have lower returns on capital than highly concentrated ones.

Conclusion

While there is plenty of anecdotal evidence that significant parts of the stock market are being driven by speculation rather than investment, we don’t need to rely on anecdotes for a demonstration. The explosion in the use of derivatives that are purely speculative in nature shows a stark change in the motivations of a significant fraction of market participants. It is almost unquestionable that speculation is a much bigger driver in the stock market today than is normally the case. Speculative booms are not guaranteed to end badly, but they normally do and that seems to be particularly true in the stock market. I’d argue that an important cause of this eventuality is that the stock market is adept at giving speculators what they crave, and scarcity is necessary to keep prices above their fundamentals for an extended period.

Today’s stock market is seeing the largest burst of issuance we’ve seen in over a generation. Furthermore, the form of much of that issuance — SPACs — seems tailor-made to deliver additional supply of capital to exactly those areas speculators are most in love with at the time. While that can lead to lovely outcomes for the managers of the SPACs, it is likely to both reduce the scarcity premium of the narratives that speculators are in love with and reduce the return on capital of the fundamental activities that the influx of capital will join.

This makes me believe that the timescale for the eventual deflation of the current speculative bubble is unlikely to be all that long. What form it will take is more difficult to say. The signs of speculation are obvious in the market today but determining how wide the mania has spread is trickier. While almost all the us stock market is trading at very expensive levels relative to history, it is hard to determine whether a holder of, say, Microsoft or Johnson & Johnson is an investor who is content to earn 3% real in the long run from a high-quality company in the context of low cash and bond yields, or a speculator who is betting the company will generate double-digit returns despite its high valuation. If the whole of the market is dominated by speculators with outsized expectations, it seems likely that deflation in the obviously speculative tier will take the overall market with it. If those speculators are coexisting with investors who recognise the impact that high valuations will have on potential returns but accept those lower returns, it may be that the losses will be more contained to today’s highest fliers, who have already started showing some signs of weakness even as the market continues making new highs. Even in that case, the viability of the rest of the market seems to be crucially dependent on the combination of economic growth, solid enough to keep corporate profitability strong and not so strong as to reignite inflationary concerns. That is a tightrope that will be far from easy for the market to navigate indefinitely, but the timescale of the market’s fall from that narrow wire is harder to estimate.

How to protect yourself

If the bubble bursting takes the form of the speculative end of growth falling, the easy protection is not to own the speculative end of growth. It is not a coincidence that value today is close to as cheap as it has ever been relative to the market, but it is convenient nevertheless. You can protect your equity portfolios by choosing to bias them toward value and away from the most expensive end of growth. Doing so has the nice feature of being both risk-reducing and return-enhancing in today’s environment. If, as it did in 2000, the overall market is going to follow the expensive growth end down, a value bias will help but not necessarily make you money. For protection against a broader equity bubble bursting (or the market falling due to higher-than-expected inflation driving a repricing of long duration assets even if it wasn’t strictly a broad bubble to begin with), we would suggest liquid alternatives as a less risky way to get close to equity-like returns with lower correlation to the stock and bond markets. Of that class of strategies, our current favourite is the Equity Dislocation Strategy, which is explicitly short the high-fliers and long cheaper stocks on the other side. It has had a good start to the year, but we believe there is still plenty of room for further gains, whether the market holds on and only the specs fall or if the overall market turns lower as well.

*This is an excerpt from GMO’s Quarterly Letter Q12021. You can read the complete version on www.gmo.com. Copyright © 2021 by GMO LLC.