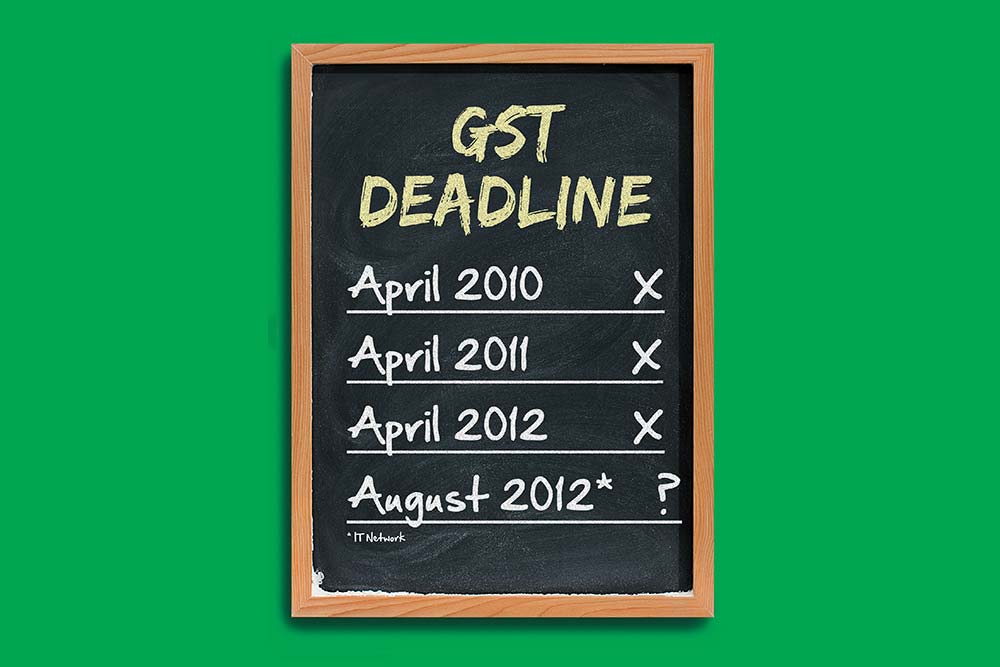

Major economic reforms cannot happen if the political realities that surround them are not in sync. The same irrefutable logic holds good for the long-awaited goods and services tax (GST) regime, which will usher in comprehensive indirect tax reform in the country. The target was to introduce GST from April 1, 2010, and this was announced in the FY08 Union Budget. Two years since, however, the GST regime appears even further away.

Finance minister Pranab Mukherjee certainly wants to herald the GST era and his latest Budget moves in that direction — in fact, he speaks of drafting the model legislation for Centre and state GST in concert with the states, and says that this is in the works. The FM even talks of an operational GST Network by August this year. But this doesn’t mean that the GST regime will be implemented by, say, April 2013. Direction apart, there’s no timeframe for GST implementation in the Budget.

The fact is, GST cannot take off till there is a constitutional amendment so that taxation will come into the concurrent list. The 115th Constitution Amendment Bill 2011, introduced in March last year, is still with the Standing Committee on Finance. Besides, there have been constant parleys since 2007 between the Centre and the states; many hurdles have been removed but some still remain, especially with the Opposition (particularly BJP-ruled states) continuing to voice concern over compensation issues and the loss of fiscal autonomy. “The Centre has not been reaching out to the states to address their apprehensions and concerns,” says Sushma Swaraj, Opposition leader in the Lok Sabha. The political scenario is also changing now that the 2014 general elections are not too far away. So, forget the current fiscal, the question now is whether the UPA government will be able to implement GST during its tenure at all.

“Any big reform is bound to face some delays,” says Sushil Modi, deputy chief minister of Bihar and chairman of the Empowered Committee of State Finance Ministers (EC). “I am optimistic that GST can be implemented,” states Ashim Dasgupta, former finance minister of West Bengal and former chairman of the EC. “It is possible through further discussions between the Centre and the states,” he says. “What is needed now is political convergence.” But that’s the biggest challenge facing the UPA government.

State of affairs

The states’ concerns are understandable. GST will subsume all other multiple layers of indirect tax such as Cenvat, service tax, Central sales tax (CST), state-level sales tax, octroi and so on. At present, the Centre can tax services and goods only up to the production stage, while the states can tax the final product. GST, through the constitutional amendment, would change that and allow the Centre to tax sale of goods and states to tax imports and levy service tax. The states worry on two counts — losing their fiscal autonomy and compensation for revenue loss on account of phasing out of CST, which is collected and retained by the states.

More importantly, there are structural issues. “Not all opposition is political,” says R Kavita Rao, professor with the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP). She feels there are genuine worries for states such as Jharkhand mopping up as much on the services front as they lose CST, given the structure of their economy. Rao points out GST would mean a standard rate for goods and services. Assuming the classification of commodities remains unchanged, the finance minister has proposed a lower rate for goods at 6% and 8% for services. An NIPFP study indicates, for instance, that for Jharkhand to get the same amount of revenue it got in FY08, the state needs to impose an 18.98% standard rate of tax on goods.

Even a 10% tax rate would mean revenue loss. “Such states need to be given flexibility for a higher tax rate,” she says. The Centre has already pruned CST from 4% to 2% with the assurance of compensating the loss during the phasing-out period. However, with the delay in GST implementation, the Centre is now refusing any further compensation. “One way to hasten the GST implementation process would be for the Centre to sweeten the deal for the states, as against its current approach of tightening the purse strings,” says Rao.

There is also a trust deficit. Modi rues things the states unanimously agreed upon were not taken into account in the Amendment Bill. For instance, Clause 12 of the Bill provides for the creation of a Goods and Services Council, which would make recommendations on all matters for a harmonised GST structure, and states that every decision would be “with the consensus of all members present at the meeting.” However, what has irked the states is the creation of a GST Dispute Settlement Authority that shall adjudicate on any complaint of deviation from the recommendation of the GST Council that results in a loss to a state or the Centre. Or, that would affect “the harmonised structure” of the GST. “When all decisions are arrived at through consensus in the Council, where is the need for a GST Settlement Authority?” asks Modi. “This is diluting the federal structure.”

Politics of priority

As of now, all contentious issues will be placed before the Sinha-headed panel. The dice will start rolling only when the panel submits its report. While the panel submitted its report on the Direct Tax Code (DTC) Bill in the early part of the Budget session, finance ministry sources say the government is keen on having the panel first give its report on the Prevention of Money Laundering (Amendment) Bill, 2011. This could mean that the report on GST will be tabled during the monsoon session of Parliament in July-August at the earliest, and possibly even the winter session. The UPA government may then consider including some recommendations of the panel before placing the final legislation for approval before Parliament.

This is where the big challenge lies. The only reason to expect the new GST structure to be implemented soon is because it’s being piloted by Mukherjee, whose political skills have been unmatched in recent times. The GST Bill, however, will be a different ballgame — it’s a Constitutional amendment and the procedure laid out in Article 368 is rigorous. The Bill will have to be passed in each House by a majority of the total membership of that House and by a majority of not less than two-thirds of the members of that House present and voting.

The UPA government just does not have the numbers to get a two-third figure unless, of course, the Opposition also votes along with it. That would seem possible in theory as the BJP supports the GST in principle. But, given the current political scenario, why would the Opposition want the Congress-led government to get credit for such a transformational reform? Especially as the 2014 general elections are not that far away.

Even if that happens, Article 368 also spells out that the Bill needs to be ratified by not less than one-half of the state legislatures before it gets presidential assent. There are 28 states and the Congress rules in 11 of them. Without BJP support, it will have to get West Bengal (Trinamool Congress), Uttar Pradesh (Samajwadi Party), Jammu and Kashmir (National Conference) and possibly Tripura (CPI-M) on board. This is assuming that the Congress manages to have the Bill ratified in the Kerala and Uttarakhand legislatures, where it is precariously placed.

Finally, FY14 will have an ‘election Budget’ — a time for sops, not bitter pills. As the GST is not a topic of mass appeal, the focus of the UPA government is likely to be on items such as the landmark Food Security legislation. To expect the GST to be top priority, then, may be wishful thinking.