Flanked by the Mahanadi River on one side and jutting the National Highway, the Jagatpur Industrial Estate in Cuttack occupies prime real estate. “There are 600 industries here, generating Rs.2,000 crore in turnover. We pay Rs.200 crore in taxes, Rs.4 crore for electricity, but compared to what we contribute to the exchequer, the government hasn’t done anything for us,” says Abani Kanungo, president of Orissa Industries Association (OIA) and proprietor of Kalinga Packaging.

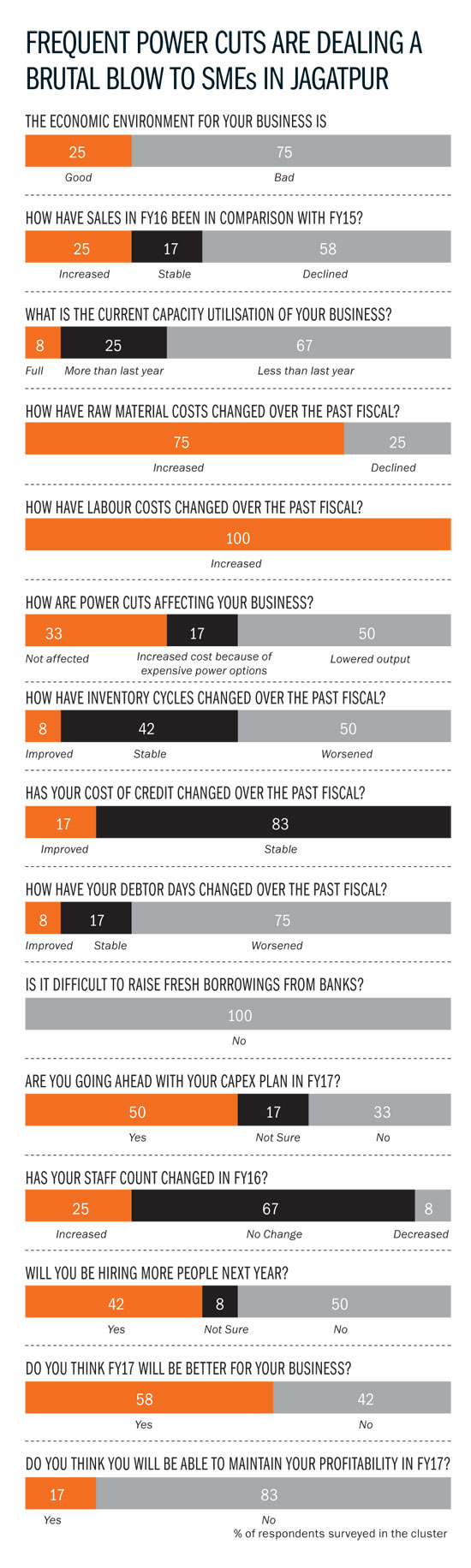

Kanungo describes the on-the-ground situation as ‘grim’, a sentiment echoed by many other SME proprietors operating in diverse sectors. Talking to them one gets the feeling of a general economic slump, making official GDP growth figures look increasingly dubious. Their complaints range from subdued demand, escalating labour wages, recurrent power cuts, and lack of government initiatives for supporting exports and building basic infrastructure within the estate.

From boom to bust

Take the case of Sunil Dhingra, the proprietor of Sunnit Auto Builders, an SME engaged in building bodies of tipper trucks, used in mining and construction. His business, highly correlated to mining activity, soared during the boom years of 2003-2008 when China was importing iron ore from Odisha and exporting steel. Since then, his business has been languishing.

“We were expecting achche din after the Modi government came to power in 2014. However, there has been little change on the ground,” he says. Things have only gone from bad to worse for Dhingra as recently a mine in Khurda district from where he got orders closed down after getting into a legal tangle. Currently, he has a turnover of Rs.1 crore, with 10% margin.

Kanungo of Kalinga Packaging also expects turnover to inch downwards, from Rs.25 crore last year to Rs.23 crore this fiscal. Kanungo supplies corrugated cartons to FMCG companies like Coca-Cola, SAB Miller, Parle Agro, ITC, and HUL, making his turnover sensitive to consumer demand. He says his debtor days are shooting up, with clients taking 50-60 days to pay their dues, up from 30-40 days earlier, whereas suppliers don’t accept credit. Kanungo hopes demand will increase, with companies like Anmol Biscuits and ITC expected to set up plants in the state. In the case of Anmol Biscuits, the announcement made in 2012 is yet to materialise.

The only succour for Kanungo is the reduction in raw material prices (paper, glue etc), but he is obliged to pass on the cost reduction to his clients. He says his margins (4-5%) are shrinking further because of competitive pressure and rising wages. Kanungo adds that availability of skilled labour is the biggest problem for SMEs, especially finding workers who show initiative and take up responsibility.

Gourishankar Acharya, promoter, Gopal Feeds has the same refrain. His company supplies cattle feed to farmers looking to boost milk production, by processing rice bran, maize, groundnut cake and sesame cake. He says competition and expensive labour have reduced his turnover (Rs.1 crore) and profitability (4-5%) compared to last year. “We have a manual plant so there’s more dependence on labour. Lot of labourers from here migrate to Surat and Mumbai causing shortfall, leading to increase in wages.” Subas Mallick, promoter of Subas Nutrition that makes ghee, sauces, and cooking oil, a Rs.45-crore business, says labour costs have increased by 30% over the last 2-3 years.

For Subransu Samantray, managing director, Paradeep Oxygen, it’s competition that’s affecting sales. His company supplies liquid oxygen to steel plants (who use it to cut iron) and hospitals. Samantray says his Rs.4.5-crore business is being affected by rising competition from multinationals like Linde, which has managed to take away the contract for Apollo Hospital in Bhubaneswar.

Poor rainfall and drought-like conditions are affecting SMEs in the agri-processing sector. “Supply is down and prices are up because of subdued production,” says Susanta Kumar Panda, managing director, Jay Bharat Spices, which employs around 600 people and has a turnover of around Rs.200 crore. He says they are covering up the shortfall in supply through imports, but are finding it difficult to maintain quality levels.

Panda’s company buys spices from farmers all over India such as Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh etc. It processes and packages the spices, and markets it under its brand name Bharat Spices using 2,000 distribution points across the country. In addition, they have diversified into the pasta business, after investing Rs.25 crore four years ago in buying Italian equipment to make pasta using sooji, water, and air as raw material. The pasta business today contributes Rs.30 crore to his turnover. He says the pasta market has ‘boomed’ recently, even in tier two towns, with major FMCG brands getting into the business.

Going ahead, Panda expects lower sales for his spices business in volume terms because of deficient rainfall. Agricultural economist Ashok Gulati recently said that this is the first time in the last 100 years that India has experienced drought-like situations for four consecutive years. This is clearly showing in the agri-processing sector. As Panda puts it, “The entire sector is down.”

A counter-productive state

Many say that industry in India exists not because of the state, but inspite of it. Power cuts and infrastructure woes are common issues throughout the country. “There is 20% reduction in output because of power cuts,” says Samantray. He says power cuts affect him severely since he runs a ‘continuous process plant’. “We have to maintain a particularly low temperature to separate the different gases. One hour stoppage means two hours idle running. For the last two months, there has been no power on weekends,” he complains. Kanungo says the estate receives very little support from Industrial Development Corporation of Odisha (IDCO), the body responsible for the infrastructure needs of the estate, despite paying an annual maintenance fee (AMC). Officially, the estate land is owned by the government and has been given out on a 90-year lease to the SMEs.

“There are no working drains here, entrepreneurs have to make their own arrangements to dispose of sewage, and even then pollution inspectors are quick to demand a bribe. There were no concrete roads till four years ago, we’ve managed to get this built after a lot of effort. Streetlights are also absent. In fact, after a robbery in a factory a few months ago, IDCO’s response was to advise owners to install CCTV cameras in their premises,” adds Kanungo.

Rabindra Kumar Mohapatra, divisional head, Cuttack division, IDCO, says, “IDCO spent Rs.1 crore over the estate to build a stormwater drainage system, but because of the flat land, we required cooperation from units in the form of an outlet near their gates for the waste to seep into the drain. Many units have not cooperated.”

In general, the relationship between IDCO and the Association seems more adversarial than cooperative. Kanungo says IDCO has started ignoring its core operation of supporting SMEs, after getting into project construction and land acquisition, which are much more lucrative. “Major industrial projects require large stretches of land at specific locations based on project requirements. IDCO provides assistance for identification of project site, alienation/acquisition of land on behalf of the project, R&R and forest clearance,” notes the IDCO website. Kanungo says because of this neglect, illegal tenements have mushroomed within the confines of the estate, along with an increase in crime rates, bootlegging and prostitution. “But government protects them as a vote-bank,” he says.

The Odisha government came out with a spate of reforms mid-2015 to encourage SMEs including a single-window scheme to expedite regulatory processes pertaining to setting up of new manufacturing units. This, after an RTI filed by activist Pradeep Pradhan revealed in December 2014 that successive state governments in Odisha had done nothing to formulate a coherent land allotment policy.

Under the single-window scheme, for all projects with investment of less than Rs.50 crore, authority is vested under District Industries Centre (DIC) instead of state-level interference. “All proposals with proposed investment greater than Rs.50 crore are evaluated and assessed by the State Level Single Window Clearance Agency (SLSWCA). However, for projects with proposed investment of greater than Rs.1,000 crore (approximately US$160 million), a special High Level Clearance Agency (HLCA), headed by the Chief Minister, has been constituted for clearances,” notes a government website.

In addition, the government has set up a District-Level Facilitation Centre (DLFC) to “guide investors, assess project proposals, for follow up, establishment and operation of the units”. Divisional Heads of IDCO have also been given the power to ‘allot land’ to manufacturing units up to one acres, along with the right to issue NOCs for mortgage loans. For more than one acre, the project proposal is forwarded to a state-level Land Allottment Committee (LAC), says Mohapatra. According to him, these measures have reduced the time taken for processing project proposals from six months to two months.

However, Kanungo says the effects of the reforms are yet to be felt on the ground. “DIC doesn’t have enough power, single window clearance is only in name,” he says, adding that even for taking a mortgage loan, IDCO didn’t have the right to issue an NOC until recently.

Mohapatra agrees that the single-window system hasn’t been a success. “There is still no single platform where officials belonging to various departments - labour, pollution etc can sign off on documents.” What’s happening is that instead of the entrepreneur having to shuttle between various departments with documents, the documents are automatically being moved from one department to the other, which saves time but often leads to information asymmetry between the entrepreneur and the departments, Mohapatra concedes.

Structural issues

Many companies complain about very little incentive for entrepreneurs to venture into manufacturing. The labyrinthine tax structure encourages corruption among government officials. “I pay 11 different types of tax, dealing with different inspectors, one day it’s octroi, next day it’s excise. GST will simplify this process and reduce corruption,” says Panda of Bharat Spices. Mallick of Subas Nutrition, who sells his products in 14 states, says GST will reduce his manpower costs. Right now, operating in India is like operating in 29 different countries with different tax structures.

India is a nation of middlemen. There is very little incentive for anybody to get into manufacturing, when you can become a trader and earn a big risk-free margin instead of having to comply with numerous regulations. “I have 35 different licenses to renew every year and other hassles. Even then, my dealer’s turnover is more than mine. When I sell him Rs.1 crore worth of oxygen, he makes Rs.4 crore on it,” says Samantray of Paradeep Oxygen. Panda also complains about middlemen, who have a vice-like grip over the agricultural produce market. “The structure is such that the producer gets a pittance of the final retail price. If you buy 1 kg of turmeric directly from the farmer, it costs you Rs.80, from the wholesaler it’ll cost you Rs.125,” he says.

Businessmen also talk of unscrupulous promoters siphoning off money from bank loans by lining the pockets of bankers. Their units eventually turn sick, while the promoters reap the rewards. “There are some people who have untold amount of land, but their units are somehow sick,” says Kanungo. Entrepreneurs also complain of excruciatingly slow processing of export orders in Odisha, a major roadblock for ‘Make in India’, which presupposes its success on a resurgent export-oriented manufacturing sector. “In spite of ports like Paradeep in Odisha, I have to transport my goods all the way to Nhava Sheva in Mumbai or Haldia in West Bengal in order to export. Meanwhile, mines export without even bills,” says Panda. He exports spices to markets such as UAE, Malaysia, Singapore and Nepal. To circumvent this problem, he is planning to set up a warehouse in Dubai. He plans to use this to store large shipments, from where he will dispatch smaller containers to clients across the world. Until these problems are resolved, many like Dhingra maintain an outward facade of optimism because, “Ummeed pe duniya kayam hai.”