I was never a very good student. I had no dying ambition to top the class or get into the best university. I don’t know why but I never thought of it as a great accolade and always felt there was more to life. My father wasn’t okay with it, and as it turned out, I could not get into St Stephen’s because my marks weren’t good enough.

At some level I was very secure. I thought about stuff in my own way and did not want to follow the herd. I remember the Beatles had come to Bombay. I was in Cathedral when one of my friends said, “Let's go stand outside the Taj Mahal Hotel and see the Beatles.” And I replied, “Why would I do that? I want to hear them sing, not see their faces.”

This self-comfort has played a part all through my life – giving me the confidence to do whatever I set out to. I was the youngest of three kids with an elder brother and sister whom I looked up to, but my father was my idol. He was noble, elegant and very thoughtful. I learnt a lot from him but the most important was never to act petty or get distracted by nonsense. I rarely heard him bad mouth others. He was not warm and cuddly but I loved him for his sense of fairness.

He inculcated the love of reading in all his kids and was a tough taskmaster. When he was the general manager at ICI’s Rishra plant in West Bengal, he sent me to work for a month on the lathe machine during my school vacation. When we moved to Bombay, he made me work at the laboratory of ICI’s chemical plant. We could easily have been pretty spoilt as kids but weren’t. We were taught to do things ourselves — even now I get embarrassed if someone carries my bag.

I chose to do the same with my daughter Sonali when she returned from the US. She was in between trying to decide what to do next. I told her, ‘Sonali, I don't care what you do. You can stack shelves at the Reliance store if you like, but you have to work.” I'm proud of her because she got herself a job as a waitress in a cafe at Hauz Khas. One of my friends ran into her at the café and said, “Hi Sonali, how have you been? Come, let’s catch up over coffee,” and she said, “No! You sit, I will be serving you.”

We come from a very large family — 40 to 50 family members from varying backgrounds — and we spend a lot of time together during holidays at Dalhousie. Some families were doing well and some not so well. That mingling and having to stay in a large group had a profound effect. It taught me adaptability, flexibility, acceptance of people, learning how to make friends and get along with all kinds of people. It taught us to see life in all its aspects and that learning has stayed with me for good.

We come from a very large family — 40 to 50 family members from varying backgrounds — and we spend a lot of time together during holidays at Dalhousie. Some families were doing well and some not so well. That mingling and having to stay in a large group had a profound effect. It taught me adaptability, flexibility, acceptance of people, learning how to make friends and get along with all kinds of people. It taught us to see life in all its aspects and that learning has stayed with me for good.

Having spent time at St Columba’s School in Delhi and La Martiniere in Calcutta, it was a revelation moving to Cathedral in Bombay, following my father’s transfer. In my previous schools, we could not step out of the gates during the day. But in Cathedral, the gates were wide open. Students were walking out for lunch. I couldn't believe it! The first few days I kept looking around wondering if a guard is going to come after us. Then it dawned upon me that the school had placed its trust in you! It showed me that you could be trusted at a very young age and if you trust people they respond extremely well. That's a management lesson I have carried with me for the rest of my life. That is the reason Clix Capital’s office looks the way it does. There is neither a security guard nor a receptionist as I believe you have to leave it open and let people do what they want. You can't be an entrepreneur if you don't trust people and if you don’t trust people, you can never scale.

***

My most formative years, was the time when I was in Shri Ram College of Commerce and lived with my cousins in Daryaganj. We were 12 of us staying in three rooms. We used to sleep on the terrace, where one could hear the filmi dialogues from the nearby Golcha Cinema. Daryaganj was seminal as I saw talent at all levels of society. I developed enormous respect for people who hadn’t been as lucky. It reinforced how much of a role luck plays in life and not to overestimate your achievements, but recognise that luck and timing will always be there and you have to grab it. It would turn out to be a recurring theme in my life.

My class attendance in college was 25-30% as my time went into sports, watching movies and playing teen patti with nothing at stake. The biggest learning at Shri Ram was how to live without any money and make do with bread pakoda at the end of the month!

My class attendance in college was 25-30% as my time went into sports, watching movies and playing teen patti with nothing at stake. The biggest learning at Shri Ram was how to live without any money and make do with bread pakoda at the end of the month!

After my graduation, I got my first break with Lovelock & Lewes in Calcutta. My job involved going through the Calcutta Tramways Company’s tram ticket books and checking them with a marker against the register of tickets issued. That stint was a defining moment as it hit me that this is not what I want to do.

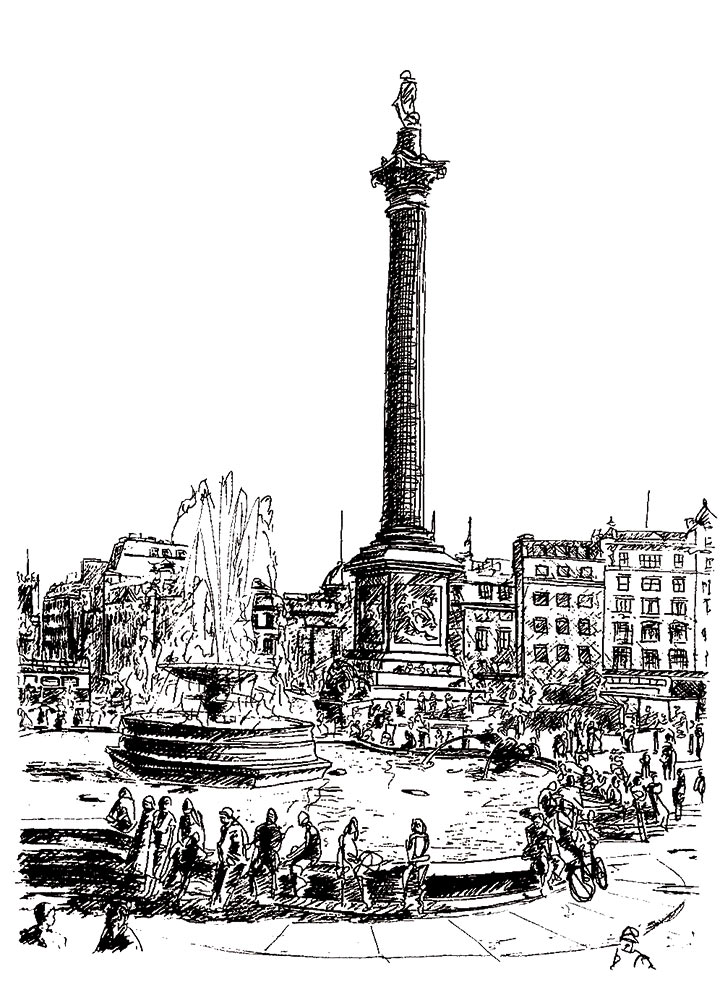

I was desperate to get out. I applied to many firms in the UK for my articleship but got rejected by everyone. Then Thomson McLintock & Co sent a fax to my father’s office stating, “Better show up in the UK within the next 10 days. Otherwise you will skip a year of the articleship.” Those were the days when even £100 was hard to come by from the RBI but my father used all his contacts and put me on a plane to London in 1972. Had that fax not arrived, I don't know what I would be doing today. Can I say that I truly deserved that break? No! I got to the UK with the help of family. Was I lucky? Absolutely! Could I ever take that privilege for granted? Never!

What astonished me about Britain was that a country of its size once ruled half the world! In London, I made great friends, who exposed me to literature, culture and art. I suddenly discovered this fascinating new world while trying to pretend that I was doing some work. I was lucky that I did not get fired. It was a lesson in how not to do your articleship!

Accountancy is fundamentally boring but I had come to London to study precisely that. Hence, it did not help that I was failing my exams. It was not a good feeling – I had two cousins studying with me, who were toppers. It must not have been a great thing back home as my father played golf with their fathers. I presume the conversation might have gone like this — Cousin’s father: My son stood first again. My father: My son failed yet again.

***

In London, I was more interested in exploring life than studying. I carted over my interest in cricket and started playing for the International Students House. I was a leg spinner in England, an oxymoron and used to get into the team most of the time because I was the only one with a driving licence. Bundled into the van were eight Pakistanis, three Indians, two West Indians and we would emerge grimy-looking and scare the shit out of every pub owner nearby. Some of the Pakistanis that I played cricket with became my closest friends.

Those days of club cricket taught me strategic thinking. I was a leg spinner but the ball wouldn't spin much and the batsmen would hit you out of the ground, so line and length mattered as much as planning. I realised that my bowling won’t get them out, but they were going to get themselves out if I stayed consistent, and did the right thing over and over again. It taught me to maximise my talent by working with everybody around me because my own talent was insufficient. It really started teaching me how life has to be lived and also infused humility in me. By not having the highest IQ in the world, I learnt very quickly that I should get the highest IQ all around me.

The other thing that taught me strategy was our interest in girls. We Indians at the International Students House were nerds in glasses and around us were tall, handsome Italians, Iranians and Pakistanis. If they walked into the same room as us, the girls would abandon us and move to them immediately. We realised, aise toh baat nahi banegi!

The other thing that taught me strategy was our interest in girls. We Indians at the International Students House were nerds in glasses and around us were tall, handsome Italians, Iranians and Pakistanis. If they walked into the same room as us, the girls would abandon us and move to them immediately. We realised, aise toh baat nahi banegi!

Pretty soon the next batch of European girls was to arrive and if the status quo persisted, we would have no option but to watch the canoodling from the sidelines. We desperately strategised to come to grips with the situation and our counterattack involved getting elected to the International Students Body. We stood for elections and my friend became the president. I became the secretary, somebody else the treasurer and we basically got the keys to the house. So whenever a new batch of girls would come in, we would get wind of it from the reception and would quickly organise a welcome party for the freshers. I was the disc jockey and ensured that none of the dashing Iranians or Pakistanis would be invited. This way, we had all those who were new to London to ourselves for a while. Our strategy essentially was to go around competition. There was no point competing head to head as they were far better.