In July this year, Think and Learn Pvt. Ltd (T&L), the parent company of edtech decacorn Byju’s that hit rough waters a year ago, appointed former State Bank of India chairman Rajnish Kumar and former chief financial officer of Infosys T.V. Mohandas Pai to its newly formed board advisory council (BAC). Byju’s, India’s most valued start-up, is currently juggling multiple issues ranging from lawsuits, capital crunch and slashed valuations to governmental investigation into its financial activities, layoffs and closure of offices. While it remains to be seen if Kumar and Pai can put in place the missing corporate governance guardrails that brought Byju’s to its current state, T&L will have to make some drastic changes to survive.

One such option on the cards is removing its co-founder and CEO Byju Raveendran from his current position. This is akin to what happened with Ashneer Grover, co-founder of fintech start-up BharatePe. Both founders are in the dock for financial discrepancies. Their start-ups witnessed resignations of senior executives amid reports of corporate misgovernance and both roped in industry veterans to put the house in order. While Grover was ousted from the company, is Raveendran too headed in the same direction?

A change in leadership might not be as far-fetched as it appears, nor is it an unprecedented one. In 1985, Apple’s board of directors removed the company co-founder Steve Jobs from his operational role following conflicts over his management style. Facing significant criticism over his leadership style and pressure from investors, Uber’s co-founder Travis Kalanick resigned as the company’s CEO in 2017. Adam Neumann, co-founder and former CEO of co-working start-up WeWork, was ousted from it in 2019 after a failed IPO attempt and growing concerns about corporate governance and financial mismanagement.

Heavy Lies the Head

A start-up founder notes, anonymously, that it is up to the BAC to bring the company back on track. “While Raveendran did have many advisors earlier too, especially investors who were backing Byju’s, it is possible that they either did not give him judicious and timely advice, or he was unwilling to listen to them,” he says.

Praroop Lodha, an analyst at Samarthya Investment Advisors, feels that the responsibility for these issues does not lie solely with the founder; it is a collective failing involving the founder, management team, board of directors and investors. “The lack of questioning on matters of these imprudent decisions has contributed to challenges like devaluation by investors, delays in financial reporting, adverse impact on the company’s reputation and governance-related complications,” says Lodha.

Somdutta Singh, angel investor and founder and CEO of multinational ecommerce accelerator Assiduus Global Inc., agrees with this conjecture. “Raveendran has been credited with building a successful edtech start-up that garnered significant attention and investment. However, like any business leader, he made both prudent and less prudent decisions that impact the company’s performance,” she says.

For instance, changes in market demand, competition or economic conditions might have impacted growth and revenue. T&L’s heavy dependence on the online education model was one reason for its financial difficulties in a post-pandemic era. Similarly, its rapid expansion without adequate financial planning or resources to sustain their growth strained the company’s finances. Additionally, poor operational management, inefficient processes and lack of cost-control measures led to higher expenses and lower profitability.

A Litany of Misadventures

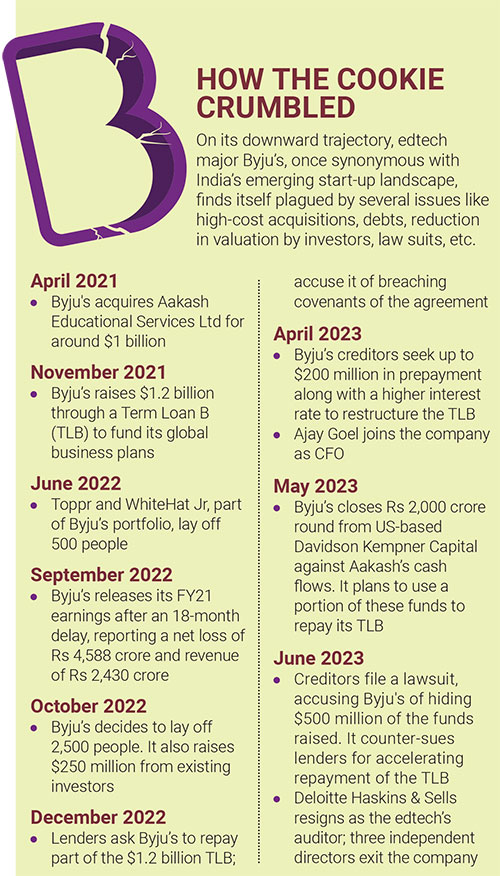

While Raveendran and his wife Divya Gokulnath founded Byju’s in 2011, the company got its second wind during the pandemic when students and their parents turned towards online education with gusto. Investors like Peak XV Partners, Prosus NV and Blackstone Inc. were only too happy to back the edtech firm, elevating its valuation to $22 billion. The money kept flowing as the company went through round after successful funding round, which it used to acquire other edtech companies. Raveendran was lauded as the founder with a Midas touch, until things started turning to dust.

Industry experts say this was because the company was busy chasing valuation over value creation in its seemingly unstoppable rush to raise funds. Moreover, its ostentatious marketing investments—sponsoring India’s cricket team and roping in actor Shah Rukh Khan and footballer Lionel Messi as brand ambassadors—coupled with uninhibited acquisitions did not result in topline growth.

In April 2021, T&L announced its ambitious plans to buy Aakash Education Services (AES), an offline test preparation company, for almost a whopping $1 billion. “This organic growth route must have appeared as a valid strategy as learners shifted back to the offline mode in large numbers. AES would have provided some fencing to Byju’s and the customer acquisition cost was likely to be lower in AES versus its online businesses,” says Davinder Singh, chief executive officer of ACIC-BMU Foundation at BML Munjal University.

Neeraj Tyagi, co-founder and CEO of We Founder Circle, a global community of founders and angel investors, also finds it probable that the acquisition spree of Byju’s was just a way to show profits in its books to justify its $22 billion valuation. “However, none of these acquisitions has been profitable for Byju’s. Additionally, the acquired companies dragged down T&L’s overall revenues, because they were not generating enough revenue to offset their acquisition cost,” he elaborates.

While Aakash was considered a good acquisition for T&L, the price tag raised eyebrows since Byju’s lacked the requisite fiscal wherewithal to buy it. Securing funds for the deal, whilst continuing business as normal, was definitely a challenge. In this dire time, the company had to find ways to stay afloat, and cost-cutting measures like layoffs and shutting down of offices were not helping. Many felt that Raveendran was too emotionally involved with the AES deal, literally wanting it to succeed against all odds.

In November 2021, Byju’s raised $1.2 billion through a Term Loan B (TLB), where it had to pay 5.5% interest with 0.2% LIBOR, a benchmark interest rate for unsecured short-term loans. “Raveendran then struck a deal with investors like the Qatar Investment Authority to share profits instead of raising debts. The deal was done under exceptional circumstances and such a structured deal was also a message to other investors that he was committed to becoming profitable earlier than later,” Singh recalls.

By striking a deal with investors to share profits, Byju’s could raise capital without taking on debt. The edtech could also avoid the immediate pressure of repayment and interest associated with loans. This provided it with more financial flexibility, especially while it was facing mounting losses. However, the jury is still out on whether this was a far-sighted decision by Raveendran.

The Chickens Come Home to Roost

Raveendran’s hopes hinged heavily on Aakash’s profitability and its imminent IPO, which he hoped would also help in servicing the TLB. However, this was not to be. Some lenders pushed for faster repayment of part of the loan, putting further financial pressure on the edtech, which was already in the limelight following multiple rounds of layoffs, questionable accounting practices, the resignation of its financial auditor Deloitte and the stepping down of three independent directors.

The company’s earliest investors also started reviewing their investment in the company. BlackRock, which owns around 1% equity in Byju’s, slashed its valuation twice this year—in February, it reduced it from $22 billion to $11.5 billion and, in March, it estimated the company’s fair value at $8.4 billion. In June 2023, Prosus NV, which had invested $536 million in the start-up since 2018 and has 9.6% stake in the firm, slashed the valuation of its investment to $493 million, effectively bringing down Byju’s valuation to $5.1 billion.

Fingers were increasingly pointed at Raveendran’s capability as a leader, with questions being raised as to whether the issues confronting the company had resulted from his imprudent decisions.

According to Ashwani Singh, managing partner of 35 North Ventures India Discovery Fund, Byju’s spent over $2.88 billion on 10-odd acquisitions, including Aakash, Toppr, TutorVista, WhiteHat Jr, Vidhyartha and Scholr. “Without a long-term, and well-thought-out, vision for the acquisition portfolio strategy, individual companies lose value and direction. This erodes the initial buy-out cost for such companies without realising the benefits of acquisitions, integrated sales teams, cross-selling, rationalisation of tech efforts and size of teams or offices, etc.,” he explains. In addition to acquiring companies with weak financial performance, as per news reports, Byju’s spent over Rs 2,000 crore on marketing during FY21.

A Bleak Future?

While Byju’s revitalised the edtech segment, it is staring at fiscal collapse, from which it might not recover. Many hope this situation does not come to pass and the company can refocus on fundamentals like unit economics and profitability, even if it means slow growth. The constant scrutiny from regulatory authorities following the corporate governance mishaps at Byju’s has instilled uncertainty amongst all stakeholders, with giant question marks appearing on the larger investment landscape.

Moreover, it would cast aspersions on the prospects of India’s start-up landscape, the third largest in the world, and keep investors at bay. This is something the government would like to avoid at all costs.

As the beleaguered Byju’s tries navigating through throes of crisis, will its investors and the newly constituted BAC push for leadership changes to help the company navigate through a turnaround? Will Raveendran’s fall from grace result in his head being placed on the chopping block?