Madhavaram is a neighbourhood in North Chennai best known for its milk colony. In the early 1990s Aavin, the state-owned cooperative, decided to set up base here and since then, it has become its central dairy. The suburb has transformed itself from being a relatively unknown neighbourhood to now having many a multi-storied structure and becoming a part of the city’s efficient transport system.

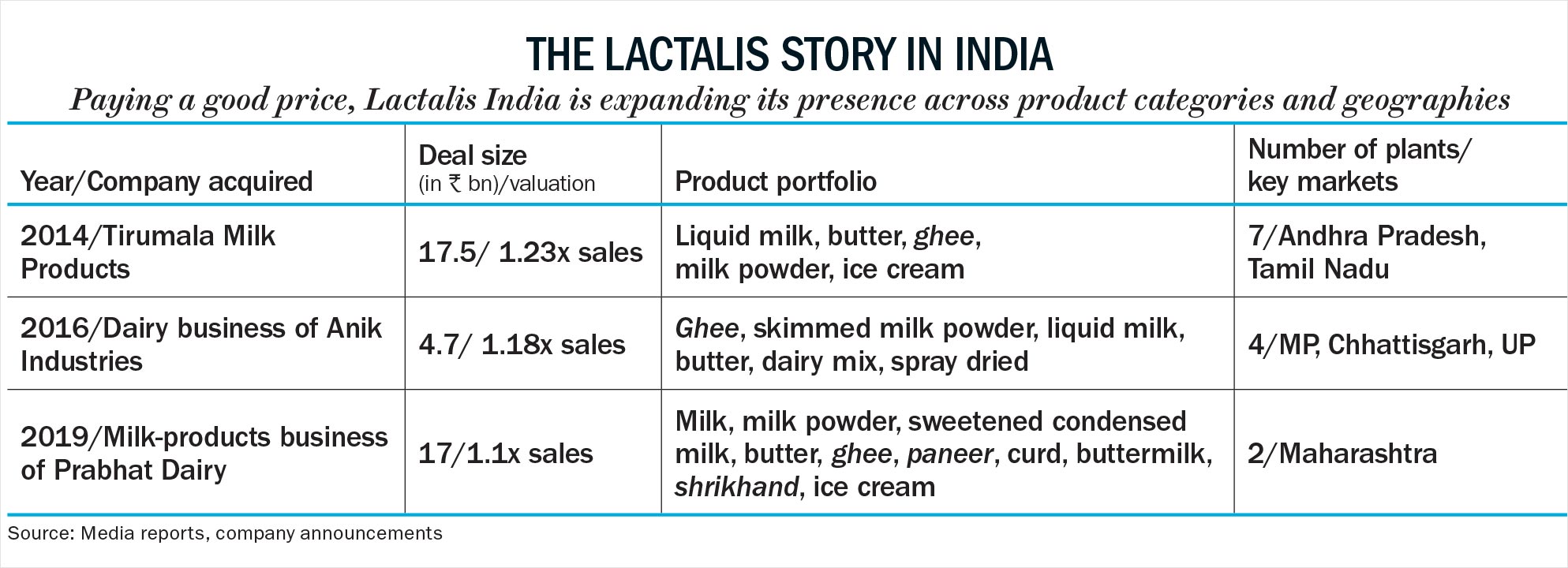

Tucked away in a corner of Madhavaram is Tirumala Milk Products’ corporate office. The large glass building is no more impressive than any other in the vicinity and betrays no sign of its ownership. In January 2014, Tirumala was acquired by Groupe Lactalis SA (Lactalis) of France for around Rs.17.5 billion. Globally, Lactalis is a €20 billion company with a presence in over 40 countries with 240 manufacturing units.

Tirumala is a Rs.20-billion company; its revenue was Rs.14 billion at the time of the buyout in 2014. It makes most of its money — 80% — from fresh products such as milk, dahi, lassi and buttermilk, and the remaining from value-added products such as paneer, ghee and ice cream. Tamil Nadu is its largest market, bringing in 30% of the revenue; Karnataka contributes 25%, and Andhra Pradesh and Telangana together 45%.

It is a humid Saturday and Rahul Kumar has just asked for some black coffee. His room is spartan and the table is filled with papers to be looked at. “I travel at least two days a week to be in the market and have just got back,” he says, explaining the messy table. Kumar has been the managing director of Lactalis India since March 2014 after a two-decade stint at Amul. The announcement to acquire Tirumala was done two months before he joined and that has been followed by the buyouts of Anik Industries’ dairy business with its Rs.4 billion turnover for Rs.4.7 billion in 2016 and the milk-product business of Prabhat Dairy with a Rs.15.45-billion turnover for Rs.17 billion (or 1.1x sales) this January

After the buys, Lactalis in India has a revenue of Rs.34 billion and procures 2.6 million litres of milk per day, highest among private playersin the country. Hatsun procures 2.3 million litres per day (mlpd).

Taking the inorganic route in India has been a first for an international dairy. Most players set up shop here and outsource production or decide to import their brands and retail them. Both strategies have failed. By not procuring the milk, they have limited control over cost. Also, without control over production, the portfolio is restricted to value-added products, which limits their distribution. Danone has shut shop, while Fonterra is back with Future Group through a joint venture — its second innings, after exiting in 2009, parting ways with Britannia.

India’s organised dairy market is Rs.1 trillion in size, and unorganised is 4x to 5x that, but it is complex and multinationals have been wary of taking on the feisty cooperatives. The share of liquid milk is 65%; ghee holds the second-largest slice at 15%. The effort is not viewed as being worth it since margins too do not justify it. Kumar admits it is not easy since cooperatives are backed by the government and get a subsidy (Rs.5-7 per litre) as well. The margins to be made are also thin.

“Liquid milk sold by private players is more expensive,” he says, when compared to that by cooperatives. But, Lactalis is in it for the long-term and plans to continuously enhance its product portfolio.

On The Prowl

Lactalis is shopping for more, even after spending a handy Rs.40 billion in the buyout of the three companies (see: The Lactalis story in India). To Kumar’s mind, there is still scope for consolidation in the dairy sector and he speaks of market potential existing both in north and east India.

Tirumala has given him a foothold in the south, while Anik has opened up the states of Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Uttar Pradesh. Prabhat gives the company a presence in western India, especially Maharashtra.

Kumar admits that there is some distance to travel for Anik and Prabhat, but adds that there is a huge scope to expand the market. This is where the role of the private players become critical, he says, since there is only so much that a cooperative can do. The other private players in the regions where Lactalis operates, include Hatsun, Dodla, Jersey, Gopaljee, Paras and Gowardhan.

It is a troublesome market. So why did Lactalis decide to take the acquisition route? It was around 2010 when it started looking at the Indian market with more than passing curiosity. The strategy of Lactalis, explains Kumar, has been to work with the strength of the local market. “A greenfield project would have taken 15 years to reach a point of maturity. With an acquisition, you work with a base and do not compete with the one you acquire, which is usually the market leader,” he says. He expects the payback from Tirumala to happen in two to three years. Kumar says that the other buyouts are also in investment mode and payback is on track, without sharing more details.

Devendra Shah, chairman, Parag Milk Foods, points out that Lactalis’ strategy here is in line with what they do globally. “The approach has been to acquire a running dairy company and have a focus on milk procurement. It is deep rooted in their DNA,” he says. According to Kumar, Lactalis has made over 100 buyouts over the last 15 years globally with none of them ever being sold. In the past decade alone, the company has made buyouts in countries such as Spain, Italy, Egypt and the UK.

The buyout strategy came with a simple approach — get the best out of the existing brands and the local market. That is a marked departure from the typical multinational way, where their bestselling global products are brought in soon after a buyout. Lactalis, in fact, has only widened its local product portfolio with the inorganic approach. Since its entry five years ago, it has added cheese, condensed milk, buffalo ghee, skimmed milk powder and shrikhand to name a few. For Lactalis India, 60% of the revenue comes from fresh dairy and 40% from value-added products. “It is important for us to reach out to a large base of consumers and that could come from anywhere,” says Kumar.

An example is that of Prabhat Dairy, for whom 70% of the business comes from the B2B segment, which includes supplying condensed milk to Mondelez for its Cadbury chocolates or skimmed milk powder to Abbott Nutrition, the makers of Pediasure. “B2B is a huge market and accounts for over 20% of the overall dairy business,” he explains. But, now Prabhat will build on its B2C, liquid-milk business, which currently brings in only 10-12% of its revenue. Kumar says the plan is to increase its share to 20% over the next two years. “We will expand milk procurement across Maharashtra. Today, the milk procurement is restricted to Ahmednagar and we will invest in infrastructure such as coolers and chilling centres,” he says. The other 18-20% of Prabhat’s revenue come from value-added products.

With Tirumala, Lactalis has decided to leverage its Rs.500-million ice cream business, selling 400 litres per day. Since India’s organised ice-cream business is still nascent at approximately Rs.100 billion, or only 10% of the organised dairy market, there is a rationale to remain in the business. Also, diversifying the brand can help reduce its dependence on liquid milk. Today, 80% of Tirumala’s revenue comes from fresh dairy and 20% from value-added products. Kumar says an ideal proportion would be 65:35 or 60:40.

Besides making the best of the local brands, they are keeping out unsuitable products from their global portfolio, even if they are hugely popular elsewhere. “We are very big in cheese globally but India is all about processed cheese. There will be an appropriate time to bring in our range but we are in no hurry to do that,” adds Kumar. He says the Lactalis approach is always to go local and not force a product from its own portfolio.

Dairy is also about an enhanced product portfolio and that is an opportunity Kumar speaks of. He calls it “product filling” and cites the case of Domino’s Pizza, which buys sour cheese from Prabhat. “If they decide to launch a smoothie, we can offer the curd as well,” he explains. In reality, it goes a little beyond to see how best each company can work for itself and for the others within Lactalis India. Some moves have already been taken in that direction.

Anik is using Tirumala’s Gudur (located in Andhra Pradesh) production facility to manufacture flavoured milk to be sold in central India and Kolkata as well. Anik’s primary businesses are ghee and milk powder, while Tirumala’s strength is in milk. “These product categories can be easily moved to markets where the other company is strong. Here, we will exploit the individual distribution strength,” thinks Kumar. Old-timers will recall the Anik ghee and Anikspray brands. It was a company once owned by Hindustan Unilever, before it was sold to Nutricia (India) at the turn of the century. It was again acquired by Mirage Impex, a domestic company, before the deal with Lactalis was struck.

In the case of Prabhat, where the plant is in Ahmednagar, paneer can be moved to Bhopal, which is a day by road. “We are looking to move Anik’s skimmed milk powder from its Dewas plant to Kochi and bring back a product (anything from the Tirumala portfolio such as ghee or butter) that can be sold in the north,” he says.

Back To The Basics

A key component of Lactalis’ strategy here lies in milk procurement, much as it is in any other part of the world. Kumar is quick to point out that even in France, as much as 25% of the total milk produced is procured by Lactalis. That obsession, clearly a hangover from his Amul days, is evident at Lactalis as well.

Take the case of Tirumala. At the time of acquisition, the company worked with 250,000 farmers to procure 900,000 litres of milk per day. Today, the base of farmers has increased to 400,000 and across south India, it procures 1.2 mlpd. Hatsun procures 2.3 mlpd, Heritage 800,000 litres per day and Aavin 3 mlpd. Anik moved from procuring no milk at all in central and north India to now buying 300,000 litres a day, and selling under the Anik brand.

Just what is it that makes milk procurement critical and strategic as well? According to Kumar, it has a serious rub-off on the entire business. “If you buy liquid milk, which is most frequently consumed, it increases the probability of buying more dairy products from the same company,” he says.

It is a line of thinking that is highly favoured. Hemendra Mathur, co-founder, ThinkAG and an industry veteran, says it increases Lactalis’ ability to drive a hard bargain with the retailer. “One will be hard pressed to think of a scalable dairy model in India without milk. It is very difficult to penetrate mom-and-pop stores with just value-added products,” he thinks. Besides, there is a limit to how many times they are purchased each month, compared to milk which is a product of daily consumption. In his opinion, a region-wise approach to milk in particular is a smart thing to do. “In the west, milk comes in bottles and stored at ambient temperature, making it easy to transport. In India, it is uneconomical for it to travel beyond 100-150 km, largely because of the perishability of the product.”

Others in the dairy business easily admit to the difficulty in creating a robust business model devoid of liquid milk. Parag Milk Foods’ Shah speaks of the advantage of having started his business from scratch with procurement at the core of it. Between Maharashtra and south India, he today procures 1.8 mlpd, with 1.2 mlpd coming from the former. “It becomes easy to move into businesses such as cheese and butter,” he says. Today, 80% of his business comes from value-added products, which Shah maintains would have been difficult without liquid milk.

Unfortunately, this is where most multinationals do not find the going easy. After all, liquid milk forms a miniscule part of their global portfolio, estimated to be no more than 10-15% for the biggies, leading to reluctance in adapting to the peculiarity of India. Jochen Ebert, who was earlier managing director of Danone Food & Beverages India and now an entrepreneur based in Munich, emphasises on the key difference between Lactalis and a company like Danone. “Lactalis is primarily a milk model and Danone is about value-added products,” he says. That remained a hurdle for Danone in India and the company was soon to realise that competition in the value-added segment was intense, with both the private sector and cooperatives not letting go.

The option that most multinationals go with is to have a limited portfolio reaching out to a niche audience. This could be a misreading of the market. “If you choose to restrict your product to modern trade, you lose at least 90% of the population,” maintains Ebert.

It’s not as if Danone did not look at the acquisition route. Ebert says companies such as Tirumala, Creamline Dairy (now a subsidiary of Godrej Agrovet) were among those considered. “The problem was that they all had a large liquid milk business, which Danone does not do even in France (its home market),” he explains. Besides, the dairy major was used to making 12-15% margins globally, while liquid milk would barely give half that. Being in the liquid business is all about high volume and low margins.

Danone bid goodbye to India last April after selling its dairy factory in Sonipat, Haryana, to Parag, where yoghurt and curd, among other fresh dairy products, were manufactured. Two months ago, Shah decided to procure milk in the area and today does 75,000 litres per day. The plan is to double that by the end of next year. With his value-added products such as curd and cheese making a mark in the west and slowly in the south, it is only a question of time before he moves that to the north, with the help of the plant. “If you have to get it right in dairy in India, procurement is most important, followed by distribution and the product mix,” says Shah. Ebert echoes the view on distribution and points to how Danone had always dealt with organised retail in Europe, the US and more recently, China.

“In India the mom-and-pop stores was a new concept for us and distribution became an issue. It is all about a distribution game where you can have a great strategy but execution is where things can come apart,” he thinks. For Tirumala, milk moves from the factory to its 300 distribution outlets spread across south India. From there, it makes its way to the 10,000 kirana outlets. This is a distribution system Lactalis set up two years ago. The plan is to double the number of outlets over the next two to three years. These outlets also double as brand outlets/parlours. Kumar says they will have a similar model for Anik and Prabhat.

The liquid milk story has also had ITC making a foray late last year, but only after its ghee was launched. R S Sodhi, managing director, Gujarat Co-operative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF), the owners of the Amul brand, says milk procurement is a time-consuming exercise, which demands a lot of trust from the farmers. He should know a little bit given that his organisation procures 2.3 mlpd, up 10% since last year. “You have to be ready for low margins and that is why most multinationals do not take this approach. Besides, the entry of more regional players in food has made it difficult for national players to make a mark. Dairy is no exception to that,” explains Sodhi. While he concedes that there is a market for value-added products, margins will be under pressure since the number of players too has increased.

In a country where demand continues to grow despite a complex consumer base, a truckload of patience is not just an advantage but a necessity. By the looks of it, Lactalis has made the right moves. At least for now.