It turns out I’ve been naïve. I’ve spent twenty-five years writing about technology companies, and I thought I understood this industry. But at HubSpot I’m discovering that a lot of what I believed was wrong.

I thought, for example, that tech companies began with great inventions—an amazing gadget, a brilliant piece of software. At Apple Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak built a personal computer; at Microsoft Bill Gates and Paul Allen developed programming languages and then an operating system; Sergey Brin and Larry Page created the Google search engine. Engineering came first, and sales came later. That’s how I thought things worked.

But HubSpot did the opposite. HubSpot’s first hires included a head of sales and a head of marketing. Halligan and Dharmesh filled these positions even though they had no product to sell and didn’t even know what product they were going to make. HubSpot started out as a sales operation in search of a product.

Another thing I’m learning in my new job is that while people still refer to this business as “the tech industry,” in truth it is no longer really about technology at all. “You don’t get rewarded for creating great technology, not anymore,” says a friend of mine who has worked in tech since the 1980s, a former investment banker who now advises start-ups. “It’s all about the business model. The market pays you to have a company that scales quickly. It’s all about getting big fast. Don’t be profitable, just get big.”

That’s what HubSpot is doing. Its technology isn’t very impressive, but look at that revenue growth! That’s why venture capitalists have sunk so much money into HubSpot, and why they believe HubSpot will have a successful IPO. That’s also why HubSpot hires so many young people. That’s what investors want to see: a bunch of young people, having a blast, talking about changing the world. It sells.

Another reason to hire young people is that they’re cheap. HubSpot runs at a loss, but it is labor-intensive. How can you get hundreds of people to work in sales and marketing for the lowest possible wages? One way is to hire people who are right out of college and make work seem fun. You give them free beer and foosball tables. You decorate the place like a cross between a kindergarten and a frat house. You throw parties. Do that, and you can find an endless supply of bros who will toil away in the spider monkey room, under constant, tremendous psychological pressure, for $35,000 a year. You can save even more money by packing these people into cavernous rooms, shoulder to shoulder, as densely as you can. You tell them that you’re doing this not because you want to save money on office space but because this is how their generation likes to work.

On top of the fun stuff you create a mythology that attempts to make the work seem meaningful. Supposedly, Millennials don’t care so much about money, but they’re very motivated by a sense of mission. So, you give them a mission. You tell your employees how special they are, and how lucky they are to be here. You tell them that it’s harder to get a job here than to get into Harvard, and that because of their superpowers they have been selected to work on a very important mission to change the world. You make the company a team, with a team color and a team logo. You give everyone a hat and a T-shirt. You make up a culture code and talk about creating a company that everyone can love.

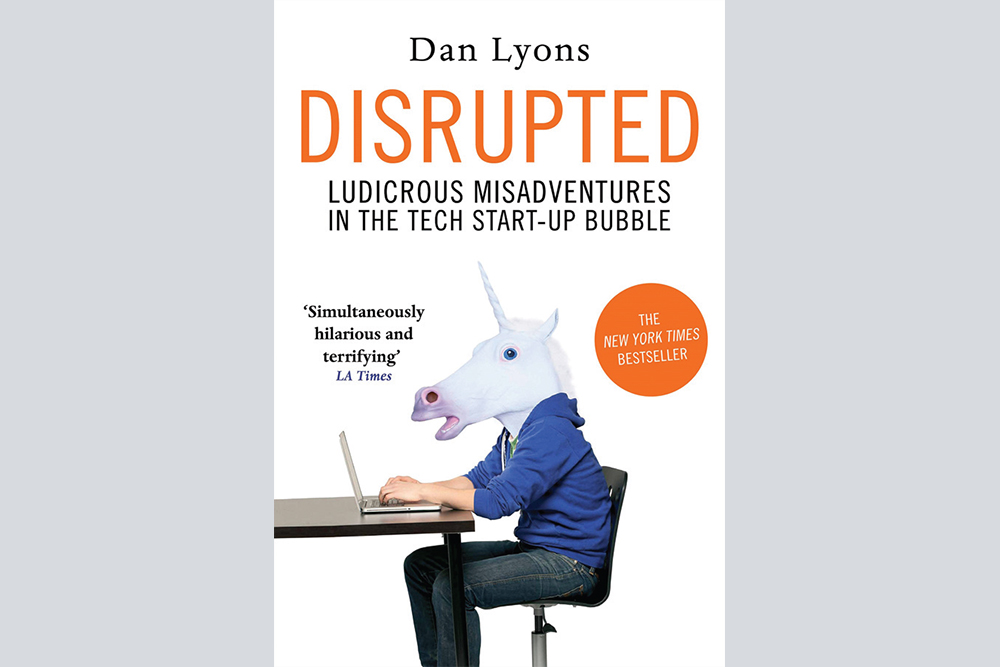

This is an extract from Dan Lyons' Disrupted published by Atlantic Books