The King in Exile is an unlikely story of riches to rags. In Mandalay in Upper Burma, the last monarch, King Thibaw, was the 41st son of the ruler King Mindon. His wife Supayalat — his main queen, that is — was the true force behind the throne, going so far as to ensure that some 80 members of the royal family were slaughtered so that no other claimants to the throne emerged. They lived a life of indulgence and opulence, yet were so anxious about coups and assassinations that they never dared leave the palace grounds. So it is rather ironic that the first time they left it was in 1885, when the British conquered Upper Burma and reached the palace ground. King Thibaw, a very pregnant Queen Supayalat, their two young daughters and the queen’s sister — also Thibaw’s wife — were forced not just to leave the palace, but were also placed in exile from their country.

After a brief stop in Madras to complete the Queen’s confinement, the family was moved to the remote coastal town of Ratnagiri in present-day Maharashtra. The British did not want the presence or even the news of the monarchy to reach the Burmese population and, perhaps, inspire a rebellion against the new rulers. Thus it was that after occupying the Lion Throne and being not just a King, but considered a God in his kingdom, Thibaw and his family began to live in a modest bungalow on a relatively-paltry sum of Rs.5,000 a month. Alienated from their land, subjects, religion and their money, the King and his family (now up to four princesses) lived an isolated, brooding existence in Ratnagiri. Initially, they pawned and sold the jewellery they had carried with them and when that was extinguished, they bought things on credit that they could never afford to repay. The King spent most of his life appealing to the British for a higher allowance, a larger residence and the right to be addressed as His Majesty.

The King died in Ratnagiri in December 1916 and his remains, as well as those of his junior queen, are still entombed in Ratnagiri. After this, the family was finally allowed to move to Rangoon. But for the Queen and the four princesses, the rest of their lives were spent unsuccessfully controlling the damage of their 33-year exile. The princesses were never formally educated and the matter of their marriage was endlessly delayed while suitable pure-blooded princes were sought. The young women fell madly in love with and married “unsuitable men” and for some of them, life was a shocking slide to eventually begging for alms. The Fourth Princess (the princesses are referred to by the order of their birth, not names) was seen as the one most likely to be a troublemaker and even the decision of how the princess’ children would be schooled and the names by which they would be referred to was decided by the British.

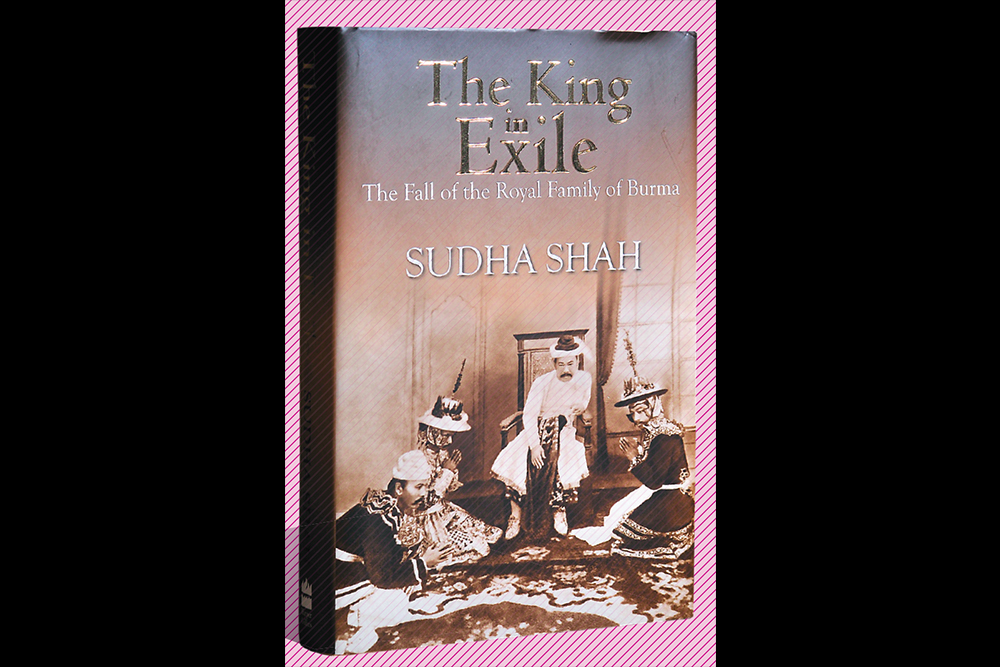

Sudha Shah, the author of The King in Exile, first read about the Marathi-speaking princess in Burma in Amitav Ghosh’s The Glass Palace. She was so intrigued to know what happened after that she began researching the life of Thibaw and his family. While the book is entirely non-fiction, Shah rightly points out in the preface of the book that the bizarre twists and turns the lives of her subject took were stranger than any credible fiction could ever have been. Shah spent seven exhausting years researching the book and it’s so much the richer for it.