There is no more than a hint of a grin on Prashant Bangur’s face when you question him about his strategy. Almost instantly, the conversation goes back to 2003, when as a freshly minted 22-year-old MBA graduate, he was sent to Shree Cement’s plant in Rajasthan’s Beawar. At that point in time, Shree Cement was a company with a two million tonne capacity and revenues of Rs.484 crore, with a net profit of just Rs.6.70 crore. More worryingly, there was a debt of Rs.360 crore on the balance sheet. “We decided to go in for an expansion in 1998 and the market collapsed. Till 2003, we were in the middle of a debt trap and our strategy was only to survive,” he says slowly.

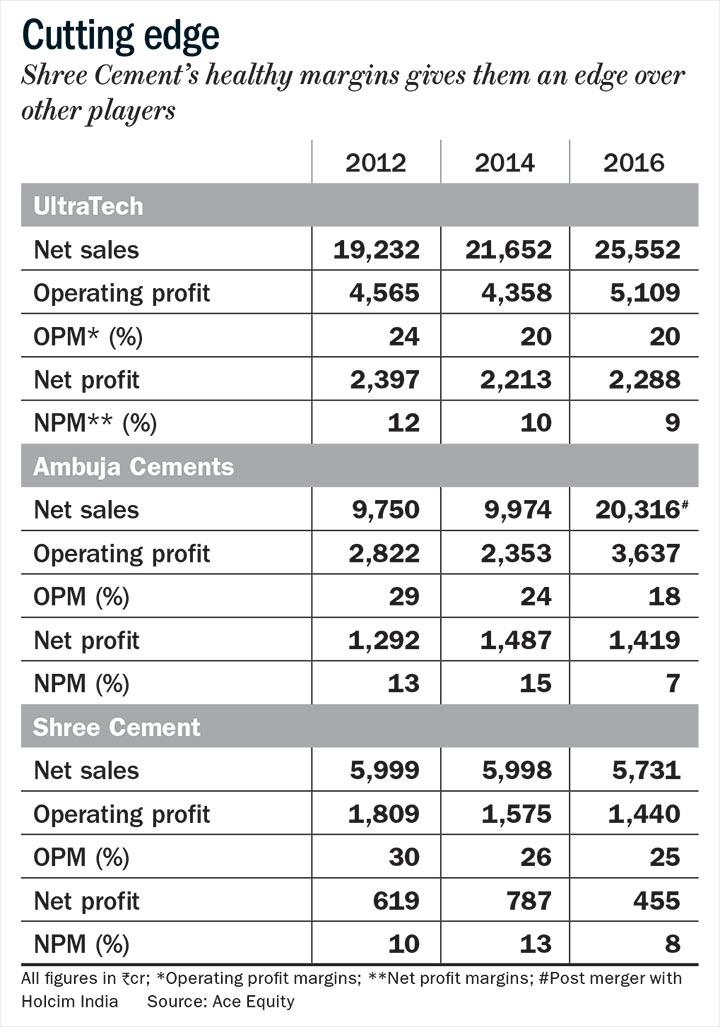

Since then, the company, where he is now the joint managing director, has come a long way. From that troubled phase at the turn of the century, the Kolkata-headquartered Shree Cement has now grown into a Rs.5,731 crore entity with a net profit of Rs.455 crore and a debt of Rs.520 crore, making it among the most well run companies in the sector. Its operating margin at 25% is significantly higher than its competitors such as, UltraTech (20%) and Ambuja Cements (18%) (see: Cutting edge).

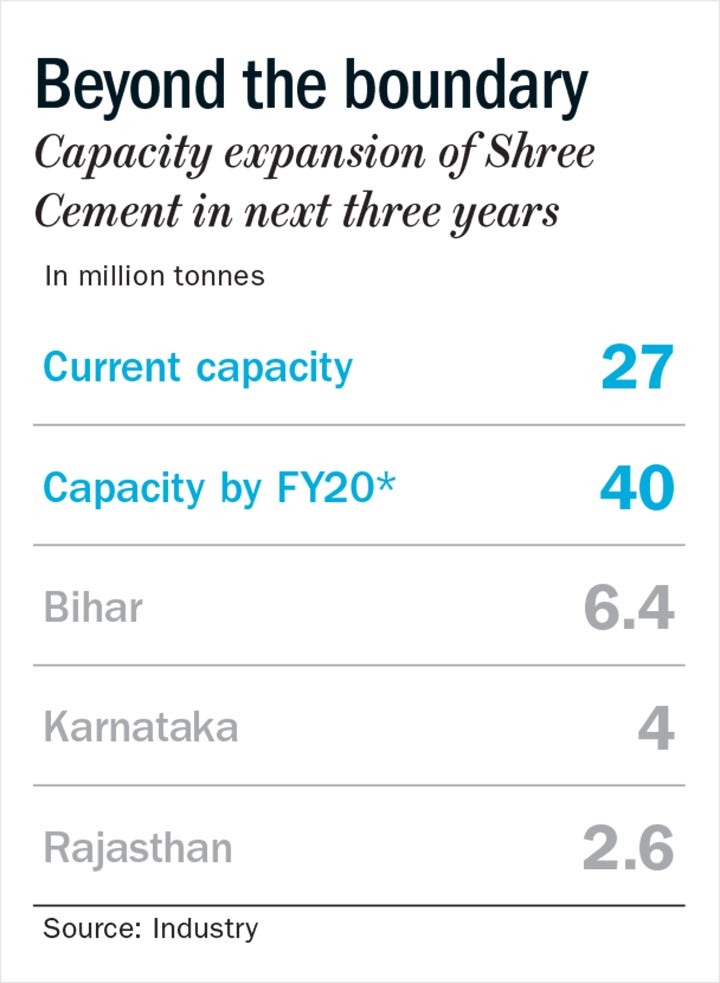

Its capacity stands at 27 mtpa, making it the third largest after UltraTech and LafargeHolcim, with a plan to go upto 40 mtpa by 2020. But going from two to 27 million tonnes was no mean feat. With Rajasthan serving as base, the company grew organically, reaching a capacity of 3.2 mtpa by 2006, which increased to 6.3 mtpa in 2008. That rose to 9.1 mtpa in 2009 and to 13.5 mtpa in 2011. Over time, it has added grinding facilities in other states in the north like Uttarakhand and Haryana apart from expanding in Rajasthan. Their proximity to the NCR region, Punjab, and Himachal helped them garner a 20% share in northern India making them the market leader. The fact that there were no serious competitors in the region only strengthened its position. “I think that [the initial] difficult period taught us the value of being conservative. It is one thing that has certainly worked over time,” says Prashant, who learnt the basics of the business from his father, Hari Mohan Bangur. The company is now looking to replicate its success in newer markets, such as eastern and southern India.

The bean counter

In the summer of 2015, two units of Lafarge India, housed in Chattisgarh and Jharkhand, were put on the block. With a capacity of over five million tonnes, they were prized assets in eastern India, where Lafarge was the market leader. This sale was a precondition for Lafarge’s $44 billion global merger with Holcim, with the Competition Commission of India requiring these assets to be sold.

Among the bidders were international names such as Heidelberg and CRH, apart from domestic players like Birla Corporation and Shree Cement. A banker involved in the transaction recalls the senior Bangur being disinclined towards the deal, stating that Lafarge did not have the lowest cost of production. When the argument about the equity of the Lafarge brand was put forth, it did not cut any ice. “If you do not have the lowest cost, of what use is the brand to me?” Bangur is said to have asked.

It is this almost maniacal obsession with costs that has stood Shree Cement in good stead. In its fourth decade of existence, the company has made exactly one acquisition and that was as recently as mid-2014. It bought over a 1.5 mtpa cement grinding unit in Panipat from the debt-ridden Jaiprakash Associates for a very affordable Rs.359 crore, a deal said to have been struck at no more than cost price. The company’s capacity then was at 17.5 mtpa. This deal brought that up to 19 mtpa. The rationale was an increased access to Haryana and adjoining states. “It was natural for Jaypee to not be there and logical for us to be there. They could not have sustained it and we needed to be in that region,” says Bangur in a matter-of-fact way.

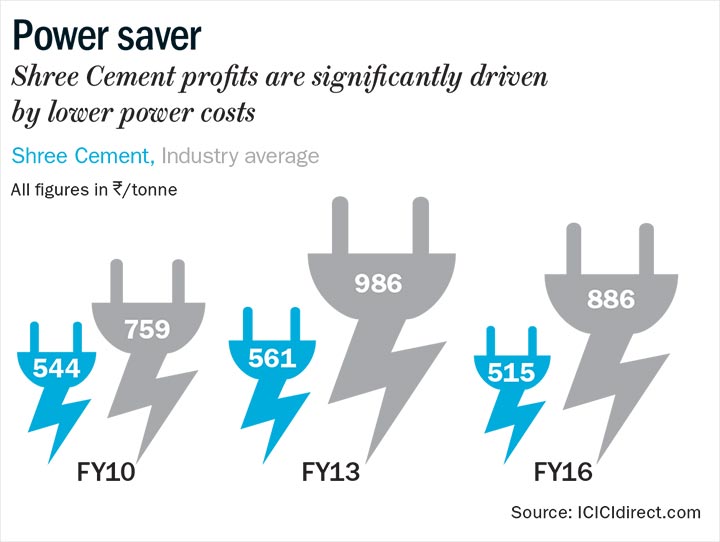

Growth for Shree Cement has been completely organic with every attempt ensuring costs never run out of control. According to Mudar Patherya, a Kolkata-based investment analyst and a long-time Shree Cement tracker, the decision to move from using coal to petroleum coke (pet coke) in 2005 resulted in costs dropping by Rs.200 a tonne. The company which began using captive power in 2003 now has a capacity of 627 MW. “Once it started using its captive power, it was a saving of another Rs.160 per tonne. These ensured Shree Cement double its EBITDA on a per tonne basis in just three years,” he says.

In time, competition did see the advantage in pet coke and was quick to adapt. Patherya says this advantage was definitely blunted, though Shree Cement was quick to look at other ways to cut costs (see: Power saver). The management set up its grinding units close to power plants that generated fly ash, a key raw material in the manufacturing of cement. In addition to this, a waste heat recovery boiler was commissioned, which allowed them to produce power at 30-40 paise per unit (Thermal, by contrast, would cost Rs.4.50 per unit.) “That saw the company save at least Rs.130 crore each year from 2007,” he explains. All this has contributed generously to a healthy bottomline growth.

It also translated to Shree Cement’s product offering being cheaper than that of its competition. In many states in north India, where for the last two to three years the average price per bag has been between Rs.240 to Rs.260, the difference at the retail level is said to be at least Rs.15 per bag (of 50 kg). “Shree Cement has a cost and volume strategy, while most players are focused on price and brand,” says a senior official at a rival cement major. On this issue, Bangur is forthright and firmly says, “We are not a premium brand of cement but one that offers good value for money. We keep it simple because our costs are low.”

If costs are one part of the story, the location in Rajasthan was a significant advantage. While competition was largely based in Chittorgarh in the southern part of the state, Shree Cement was housed in Beawar — closer to the centre with a plant in nearby Ras coming up a little later. Consequently, 60% of its total manufacturing capacity remains in close proximity to its consumers.

According to Girish Choudhary, vice president, Spark Capital Advisors, having grinding centres close to major demand centres leads to lower freight costs. “Besides, Shree Cement operates at higher utilisation levels as compared to competition, which means better absorption of fixed costs. In that sense, they have a sum of the parts approach, rather than one measure resulting in cost savings,” he says. For instance, Shree Cement operated at the utilisation rate of 86% in the north as compared to the average of 80% in the region. In the east, it showed the utilisation levels of 83%, whereas the average was at 73%.

Prashant insists that the recipe for success has really been in deploying capital efficiently and rationally. It is a point that resonates with Patherya, who is quick to add that Shree Cement’s share capital has remained ‘frozen’ at Rs.35 crore since 2003 with cash reserves of over Rs.6,000 crore. “Their accruals alone are enough to set up a new plant. Shree Cement sweats all its assets, which gives it not just cost control but economies of scale and huge cash flows as well,” he says. For instance, the capacity utilisation for the company’s plant in Rajasthan often goes up to 120-130% improving the economies of scale and reducing costs. Even for truckers, there is a weekly or fortnightly bidding, which ensures that the suppliers are kept on their toes.

Stepping outside

Like Beawar in Rajasthan, where there was no other plant in the vicinity, they were first movers in Bihar too. But it wasn't an easy start. Bangur points out that after the oil refinery in Baurani, there was no big investment in the state. “For 50 years, no one came in and we had a huge challenge on our hands. There was really no industry or any work discipline to speak of,” he says.

With a 2.6 mtpa integrated cement plant in Raipur at a Rs.1,600 crore outlay, setting up a grinding unit with a 2 mtpa capacity in Bihar’s Aurangabad district opened up the market in eastern India for the company. The decision of the Bihar government to offer a significant VAT incentive (said to be over 50%) for new entrants was the icing on the cake.

At that point, Lafarge, the largest player in the region, was transporting its finished product from Raipur and there was clearly a huge gap left open in Bihar. Shree Cement moved quickly with the grinding unit in Aurangabad district in mid-2014, which was expanded to 3.6 mtpa two years later; the plan now is to increase that to 4.5 mtpa by the end of the current fiscal, with another greenfield proposed in the east, currently estimated at Rs.350 crore.

However, a lot needs to be done for a larger presence in the rest of the east. “Logistically, we are efficient when it comes to clinker facilities. However, there is still a significant disadvantage we have on grinding, since there is only one unit in the region,” points out Prashant. Clinker is cement in the lump form, while grinding is what gives the finished product.

The east, for many years, has been characterised by high capacity utilisation levels, which has now been corrected by more players coming in. From a level of 90% in 2009, it was down to 81% in 2016 and expected to be only 73% for the most recent fiscal — still better than the overall capacity utilisation in the country, which stands at 67%.

Between 2016 and 2017, an additional capacity of 13 mtpa was added taking the total to around 65 mtpa; the total national capacity is 390 mtpa. Nirma, after the acquisition of Lafarge’s assets (11 mtpa bought for Rs.9,400 crore), remains the market leader in the east, though, Shree Cement has made serious headway in Bihar. According to Prashant, its market share in the state stands at 15-16%.

Overall, the company has 3,000 wholesalers and dealers (1,000 wholesalers and 2,000 dealers) in the state. Shree Cement’s dealers say that the company did not choose to cut prices and instead, focused on margins and schemes for the trade. For instance, the difference between margins to the wholesaler and any dealer was as much as Rs.7-8 for each bag in favour of the former. “The company dropped that to Rs.3, ensuring there was a lot of incentive for us to sell the company’s product. The message for us has been to push volumes at any cost,” adds one dealer. This has aided the process of higher market share, in Bihar significantly.

By any yardstick, the east will be one of the key markets to track. Existing companies are expanding their capacity and new players are coming in with big ticket investments. Emami, well-known for its presence in the FMCG business, is looking at this region closely to further its cement story. It has a 5.5 mtpa plant in Chattisgarh, with a grinding unit having been commissioned a few weeks ago in West Bengal.

Vivek Chawla, CEO, Emami Cement says that in spite of capacity additions in the east, 4-5 mt would have to come from the rest of India. “It is this deficit that has created opportunities for companies to set up grinding capacities here. The most distinct feature of the east market is its low per capita consumption, which has potential to grow significantly,” says Chawla.

Shree Cement is also beefing up its capacity to meet the additional demand. “The plan for the east is no different. Our grinding plants in Orissa and Jharkhand will be up in the next 15-18 months, which will allow us to expand into these two new markets,” says Prashant. Together, they will have a capacity of six mtpa. The clinker expansion at Raipur, which will add another 2.8 mtpa, will be completed around the same time. The focus on eastern India hasn’t escaped the attention of Mahendra Singhi, Group CEO, Dalmia Bharat Cement. “Our market share in the east is 12-13%. For FY18, we expect higher demand and better pricing. Low cost housing and construction of roads will be our focus. The huge rural population, especially in states like Bihar and Orissa, give us a big opportunity. In all, we see demand for cement in the region growing by 6-8%,” says Singhi.

Down south and beyond

Bangur remains reticent about the south and says he is merely ‘testing the waters.’ The region, which has a total capacity of 140 mtpa and capacity utilisation of 49%, has been characterised by lower utilisation levels and high profit margins on the back of a very strong cement cartel. The excess capacity doesn’t bother him.

According to him, for all commodities globally, excess capacity is to the extent of 30%. “If you want to wait for perfect conditions, you will wait all your life. Besides, if you do not put up capacity, someone else will,” he says. The company is putting up a four mtpa plant in Gulbarga, which is already home to names like ACC, Rajashree, Vicat, and Orient.

His rationale for getting into the south is interesting. Bangur says he would like to maintain his 20% market share in the north.“It does not make sense to take it to unrealistic levels. If you have a 60% share and ten players together have the other 40%, it will lead to a guerrilla war making it very difficult for the leader,” he maintains. With the share that Shree Cement is at today, Bangur is clear that it makes him more mobile and agile to react easily to competition. The target is to get to a similar level in the east, which he thinks is achievable in two years.

The plant in Gulbarga will give the company access to northern Karnataka, Hyderabad, and the Maharashtra belt, which includes Solapur and Pune. The plan is for the plant to be up in 20 months from now. “Selling will start only after that. The market in the south may be different, but the basic technology is the same everywhere,” he says.

It is too early to say if Shree Cement will muscle around prices in this region. “Prices have remained quite stable for about a year and half now,” says Pramod Kumar Singhania, senior vice president at Orient Cements’ Chittapur plant in Gulbarga district. His plant came up in September 2015 and boasts of a 60% capacity utilisation. “There is a lot of demand from both housing and infrastructure here. We are seriously contemplating increasing our capacity from the current level of three mtpa to another 2-3 mtpa,” he adds.

With Gulbarga’s location, Shree Cement can really spread its wings into newer markets. The company’s total investment on the expansion of existing operations and beginning new ones across markets is to the tune of Rs.6,000 crore. The expansion will be funded by internal accruals and take the company to its target of 40 mtpa by 2020 (see: Beyond the boundary).

There is little to doubt that this chemical engineer from IIT Bombay has his hands full. Till about five years ago, Bangur and Prashant would take the CAT examination for admission to the IIMs with the objective of just gauging themselves. “I stopped taking it after it moved to the computer aided format. The whole idea was to judge myself against modern talent and just figure out where I stood,” he gleefully says. With very little preparation, both father and son did fairly well each year. The bigger test could be in the expansion in east and south India, which promises to push both to the limit.