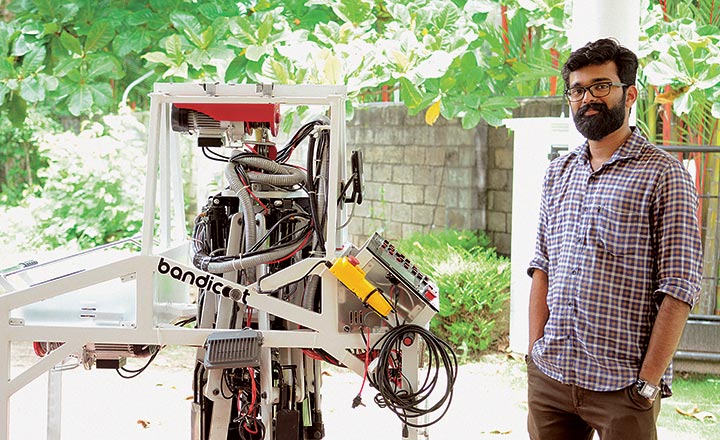

In big cities, apart from gleaming glass buildings and fast cars, it is quite common to see a manual scavenger gingerly stepping into an overflowing manhole to unblock it. He trowels out the sludge — of kitchen waste, plastic and human excreta — while inhaling toxic gases and wading through infected liquid waste. Although a ban on this practice was imposed way back in 1993 it still continues unaffectedly. Thus, to put an end to this, a Thiruvananthapuram-based start-up Genrobotics has come up with a solution. Its four-member team has built a 50-kg robot, named Bandicoot, which can clean up a manhole in 20-45 minutes. A manual attempt usually takes around three hours.

The robot opens the lid of the manhole, reaches down into it, cleans the drain floor and collects the debris.

Early days

Genrobotics was founded in 2015 by Nikhil NP, Arun George, Rashid K and Vimal Govind MK when they were studying in MES College of Engineering in Kerala’s Malappuram district, a 10-hour drive from the state capital Thiruvananthapuram. The four were also working with the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Development Cell (IEDC), set up by the Kerala Startup Mission (KSM), which connects students with the ecosystem of mentors, investors and clients.

The quartet hit upon an idea — to build a 10-ft tall exoskeleton to lift weights. This was to be used in construction, warehousing or for any task that required extra ‘muscle’ and extra cover. They put together a prototype and, on being encouraged to build on it, came up with a battery-powered robotic suit on a relatively small budget of Rs.51,000. This could lift weights of up to 50 kg. The four then upgraded it further to a generation 2.5 robot, which could lift heavier weights of up to 80 kg.

Their effort was supported by KSM but they did not make any headway. “We had to stop making exoskeletons and, in 2016, we took up jobs in MNCs,” says Nikhil, co-founder of Genrobotics. But, the hope of making “something unique in the future” stayed alive.

Rodent robot

The four continued to meet every week to discuss innovation in robotics, and frequented events of the industry to be aware of the latest trends. Soon enough, opportunity came knocking at their door. At one of the events in the same year, they met Kerala IT secretary M Sivasankar, who told them that the state government was keen on tackling the problem of manual scavenging by mechanising the process.

Soon after the meeting, there was a furore over a photograph published by a local daily — it showed a worker covered in filth. Taking note of it, the chief minister, Pinarayi Vijayan, wrote to the Kerala Water Authority and the IT secretary, asking them to find a solution to end manual scavenging at the earliest. Shivsankar recalled his meeting with the engineer quartet and informed the chief minister of their work in the field of robotics and how it could be used for cleaning sewers. The IAS officer then approached the four, who decided to grab the opportunity. “We decided to quit our corporate jobs and design a robot to clean sewers. We started working on the project in 2017,” recounts Nikhil.

They formally incorporated the company in June 2017, and approached KSM once more for funds to kick-start the project. They were granted Rs.1 million.

After extensive research, the engineers developed their first prototype that could enter sewer lines and unblock them. The robot was small — 10 kg — and because it reminded them of a rat, the team decided to call it Bandicoot. However, they had made a beginner’s mistake. They had made a solution to clear drainage lines while workers usually clear manholes, not the lines. Muck and silt gather in the sewer system in such large amounts that it collects at the entrance to the drains, and stands in the way of lowering a jetting machine. After the manhole is cleared, the worker positions a waterjet to wash out the sewage. The four, thus, sat down to re-work the design.

Drain brain

Their new prototype, named Bandicoot 2.0, was out in October 2017. When they approached Kerala Water Authority (KWA) with this device, which had a human-controlled interface to clear manholes, they decided to fund the start-up. From opening the heavy lid of a manhole to cleaning and collecting waste, the new robotic device performed a wide range of tasks that manual scavengers do.

“We have also attached five to six cameras (including night-vision ones) to the robot. So, once it enters a manhole, the operator can see the progress of the work,” says Nikhil. Since inhaling toxic gases can cause death, Bandicoot has gas detectors attached to it too. “They can measure the toxicity of gases, which can warn workers approaching the manhole,” he says.

Following the successful trial of their beta version, Genrobotics sold it to KWA. Currently, they have an order from the agency for 15 units, with each costing around Rs.1.5 million to 2 million, depending on the specifications. Civic bodies in Thanjavur, Madurai and Tiruchirappalli in Tamil Nadu, and Anantapur in Andhra Pradesh have also adopted the bots, and the company is now in talks with the central government to participate in the Swachh Bharat Mission. Their product is in demand overseas too, for instance, the Sharjah Municipality in the UAE has expressed interest in manhole-inspecting robots. The start-up plans to eventually head to under-developed countries where manual scavenging still exists, but its core focus will remain India.

The parts are largely manufactured in their unit in Thiruvananthapuram. Only 10% is sourced from other places. “Cameras and LCDs are imported from China, Japan and the US,” says Nikhil. Currently, a team of 15 members of Genrobotics assemble units at Kerala Industrial Infrastructure Development Corporation in Thiruvananthapuram.

It takes anywhere between five to 10 days to import cameras and LCDs, and the assembling can be done in around 15 days. For now, they have orders for the delivery of 40 robots by end of this year, which would rake in revenue of about Rs.80 million. Genrobotics hopes to manufacture 10 robots per month in the next two years. They are even planning to set up a larger production unit by the end of 2020 to reduce dependence on sourced material.

The start-up has started to replace metal parts with carbon-fibre parts to cut down the weight of the robot. “The initial weight was 100 kg, but we have managed to reduce it to 60 kg. We want to bring it down further to anything between 20 kg and 40 kg,” says Nikhil.

However, Genrobotics isn’t the only start-up that is leveraging technology to end manual scavenging. Sewer Croc, founded by two retired Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) engineers, K Balakrishnan and Germiya Ongolu, has built four devices to clean sewers, to detect poisonous gases and alert authorities about overflow. Hyderabad Metropolitan Water Supply and Sewerage Board is in the process of procuring 28 devices from this Bengaluru-based firm.

But Bandicoot, which has the first-mover advantage, has a clear differentiator: “The other innovation helps in cleaning sewers (mostly via waterjets), but we are making a robot that replicates the work done by a human,” says Rashid. This means that the robot lifts the manhole cover, clears the pit and then attacks the blockages in a drain.

Vision driven

While it is receiving attention from government organisations, Genrobotics has also caught the fancy of investors. Unicorn India Ventures has invested around $200,000 in the start-up. It has also won financial backing from Google India’s managing director and angel investor, Rajan Anandan.

Anil Joshi, founder and managing partner, Unicorn India Ventures, was introduced to Genrobotics during one of his visits to the state. He believes that Bandicoot can be sold widely, across geographies: “The problem of cleaning manholes is not restricted to India; it’s a global problem. This product can have a big social impact.” What also convinced Joshi and his partners to fund the start-up was the team. “We saw a promising team which has the ability to take the company global,” he adds.

Even as investors sense potential, there is one niggling problem. Their clients are government agencies and there is bound to be delay in payments, which can lead to a squeeze in working capital. Rashid agrees: “We are a small firm and we need money to keep the operations running. We do face delay in payments. To address this, we have asked the officials to give us an initial payment that can cover the cost of production.”

Another snag is the criticism that Bandicoot could leave many people jobless. Genrobotics, therefore, hopes to rehabilitate the vulnerable sewer workers by training them to use the robot, and has created a user-friendly interface for this. There is also a training app. “The workers can learn from animated videos available on the app,” says Nikhil.

It won’t be an easy change to make, but if the Bandicoots do storm into the cities’ underground, it could mean an end to an age-old, inhuman practice.