Tharun Kumar calls himself a techie. The fast-talking gentleman has some eclectic interests: cyber technology and social entrepreneurship. Between 1990 and 2013, he worked in the tech space in Bengaluru with the likes of Motorola, Cable & Wireless, Hughes Communications, Sutherland and Aujas Networks.

Between 2013 and late 2017, he served as executive director at Paradigm Environmental Strategies and it’s during this stint that he met his partners in slime: Simar Kohli Das, E Muralidharan, and Praseed KK. He is now an entrepreneur and co-founder at ECOSTP.

Cess pool

Located on the eastern outskirts of Bengaluru, Varthur Lake was once beautiful and home to many fish and birds. However, it’s now infamous for catching fire because of all the sewage dumped into it. The lake is close to Kumar’s residence in Whitefield, a popular locality in the Garden City.

Instances of the lake catching fire began in May 2013. Although an absolute stranger to the world of sewage treatment, the issue struck deep with Kumar. He claims, “There are 13 million people living in this city. When they flush, nearly half of their waste reaches the city’s lakes.”

Kumar has statistics to back his worry too. “According to the Pollution Control Board of India, out of the 29,129 million litres per day (MLD) of sewage generated, only 6,190 MLD is treated. Interestingly, this is a global problem. As per the United Nations, about 80% of the world’s wastewater is discharged into the environment without adequate treatment.”

The problem barely ends there. John Kuruvilla, chief mentor at Brigade Group’s Real Estate Accelerator Program (REAP), explains, “Current sewage treatment plants (STPs) are running on diesel power. They use a lot of chemicals, the sewage is difficult to handle, and crucially, it’s fatal to its operators.”

Holy cow

As for the STPs, in September 2017, Kumar and the other co-founders came up with a solution to treat sewage without using diesel-guzzling motors, and harmful chemicals. Their inspiration? The cow’s digestive system. Kohli, chief marketing officer at ECOSTP, explains, “For sustainable solutions, nature already has some answers.”

Consider a cow’s digestive system. It has multiple chambers and passing from one chamber to the next gives the gut bacteria enough space and time to break down food.

Second, it has anaerobic bacteria (do not need oxygen to survive). Conventional STPs use aerobic bacteria, which is why you need blowers and motors to circulate air in them. In the case of ECOSTP, the plant uses anaerobic bacteria in each of its multiple chambers, which are built underground within a building-complex.

The design runs on smart mechanics and does not require electrically powered motors. KK, the team’s ‘tech guru’, finance guy, and chief operating officer, says, “It’s built underground, there’s no motor involved and hence no energy, and neither is there a need for skilled manpower.” Once the first chamber is filled, it flows into the next chamber.

There are three processes at work in these chambers. First is sedimentation and flotation (heavy objects sink, lighter objects float). Second is the treating of the sludge by microbes. Third is filtration of the sewage through a membrane made of tiny perforated balls seeded with microbes. The membrane is made of recyclable plastic. Once the water is treated in the last chamber, the overflow is channelled into a plant-gravel filter to take out the odour.

To develop this design, Kumar collaborated with Muralidharan, who is a bio-mimicry expert and researcher at the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras (IITM). Muralidharan is the chief technical officer at ECOSTP.

Making a case

An ECOSTP is about twice the size of a regular STP; depending on application, these plants measure upwards of 12 square metre. However, the system is built underground and save for the manholes, fully sealed. This allows clients to construct landscapes (playgrounds, mock gardens) atop the STP. Nirupa Shankar, director, Brigade REAP, says, “It doesn’t require electricity, is low on maintenance and that is the way to go. Everybody wants to reduce their carbon footprint and we can do it in small ways,” she says.

The team claims that its STPs can run without maintenance for up to two years. However, they recommend cleaning the plant once a year to prevent the possibility of sludge-build-up. This is against regular STPs that require labourers to risk life and limb every month to keep the septic tanks clean.

Kumar says that the water that exits an ECOSTP unit is safe for car-washes and gardening. That said, ECOSTP is working with CoEvolve Estates in Bengaluru to process the water enough to make it suitable for bathing. Kumar jokes about a potential flush-to-tap revenue model.

He says, “We had three options of making money with our start-up. The first was to sell the complete end-to-end solution.” This model comprises sourcing the bacteria, constructing the STP for the client, and servicing. Were they to go with this model, the construction for a regular residential building would take the team three weeks and a working capital of approximately Rs.4 million. They haven’t taken this route.

“Our second revenue option was to offer an annual maintenance contract where the construction of the STP is left to the client,” Kumar adds. The third was to license the core technology.

He explains that the third one is similar to Qualcomm’s business model. The tech giant sells its chipset technology and Samsung, OnePlus, Xiaomi and the rest run their phones on them. “We adopted the third option, keeping rapid scalability and sustainability in mind,” he says.

“We sell the ECOSTP DIY Kit, where our positioning is ‘Buy the ECOSTP Kit, add concrete and the STP is ready!’” he says. The kit comprises four key components: the AutoCAD drawing of the STP; the bacteria inoculum; the plastic membrane that goes into the final stage of the plant; and the consultation. The team works as consultants with their clients.

Each of ECOSTP’s kits is priced at Rs.650,000, and the team has thus far sold 20 of them. Of these, three are up and running, while 17 are in the construction phase. It has clients in the commercial sector (BHEL, Repton School, Zoho, Tata Steel) and residential space (Geetanjali Developers, Adarsh Developers, Saakaar Constructions, and the Brigade Group).

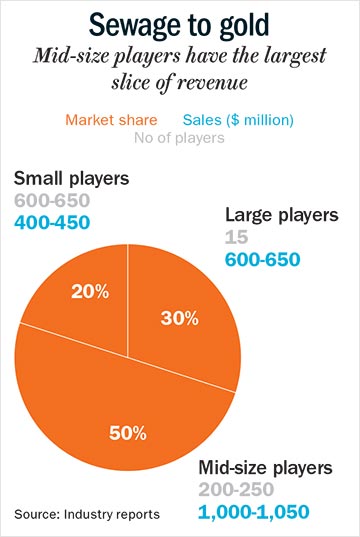

Kumar and team, still a small fish in a big sea, take on established STP-names such as VA Tech Wabag, Thermax and Ion Exchange India which dominate large projects (See: Sewage to gold). These rivals provide conventional treatment plants, which are about 20% costlier to build. However, the real clincher for ECOSTP is maintenance cost. The founders claim it is 90% cheaper.

Bridging the gap

Until 2018, the team was bootstrapped, and recently graduated from Brigade’s REAP initiative. Last year, Kuruvilla from the Brigade Group approached Kumar in Hubli. The latter was consulting with the Deshpande Foundation, an accelerator for ventures that have a social-cum-economic bent. Kuruvilla told Kumar to ditch consultancy and shift to product development.

Brigade Group was looking for the next cohort for REAP. Its accelerator programme invests in start-ups developing solutions in domains such as IoT, renewable/clean technologies, and logistics. In return, the real estate major takes a purportedly small sweat equity in the ventures it mentors. Brigade has an undisclosed stake in ECOSTP. Shankar says, “As a developer, we know how everyone loves to bash builders about how they are encroaching on lakes and other water bodies. We like to invest in companies that work on sustainability-focused solutions.” The company has already incorporated the start-up’s solution at two of its projects.

As per KK, the REAP association helps ECOSTP tweak its growth model. “How do you want to evolve business, what do you want to build over time, do you want to go B2C, and aspects such as pricing model and stakeholder management are where Brigade has helped us.” he says. In fact, it was after ECOSTP’s tryst with Brigade that the company consolidated its consultation-centric business model. “Until now, we were a set of people trying to solve a problem. But, there is a lot for us to understand, especially on the business side of things,” he adds.

In an ideal world, building construction has a defined process — a piece of land is identified, the builder plans out the structure, its water supply, waste-management systems, and then begins construction. Finally, people come and reside. But, that’s not how they do it in India. The buildings are occupied even before the developer thinks of ‘trivialities’ such as sewage treatment and regular waste supply.

To make these systems part of construction hygiene, Srinjay Sharma, executive director, Eptisa India, says municipalities of metros should bill the builders for STPs. Under such a system, societies and even commercial buildings would be connected to a trunk system, which means several smaller plants would collect wastewater in a central sewer. Sharma believes solutions such as ECOSTP will come in handy in the case of standalone buildings. He says, “They cannot handle the payload of municipal STP. For applications that require sewage treatment at scale, conventional systems will have to be used.”

The Karnataka government’s recent rule to make STPs mandatory for new buildings with 20-plus apartments could work in ECOSTP’s favour. Kumar says that the main challenge is to make real estate players see value in the concept. “Builders don’t make much of the 20% savings on construction that ECOSTP offers (compared to regular plants),” he says. But what could truly boost the start-up’s prospects is the Real Estate Regulatory Authority (RERA) Act. The law has made it mandatory for builders to maintain a project’s STP for the first five years. In effect, the maintenance cost will have to be borne by the builder. Given the low maintenance advantage, ECOSTP will have a better footing.

Saving big

So far, the team has clocked revenue of Rs.13 million and aims to raise Rs.25 million in a year. This fund will go into hiring sales and execution staff along with tech upgrades for the plants. Most notably, the STPs will be ‘IoTised’.

Kuruvilla explains a potential use case that IoT tech can solve. “There’s methane build-up that happens in STPs. A lot of the labourers who step inside septic tanks go in drunk, and a combination of alcohol and methane can be lethal. If you have devices that monitor the water quality, the type of gases building up inside, users can be cautioned to stay away from the treatment plant. In the future, the team can even develop a system of levers that will allow letting out excess gas to make the STP safe for cleaning again.”

The team has big plans for the next five years. It claims to have saved 13 million litres of water and 21 MW of power through its existing operations. ECOSTP’s expansion plan for the next couple of years looks promising too. By March 2020, KK says it will have a total of 64 projects under its belt.

According to an EY report on effective water management, treatment facilities created for wastewater suffer from issues such as improper design, poor maintenance, frequent electricity breakdown and lack of manpower. The study titled Think Blue says, “The need of the hour is to develop and deploy energy-efficient sewage-treatment systems.” Sharma of SPML is also rooting for eco solutions. “Our cities are bursting at the seams due to the waste we produce. Innovative solutions such as ECOSTP will aid the city municipality in solving the infrastructure challenge,” he says.

However, Kumar sees roadblocks. For one, there’s a lack of awareness about anaerobic bacteria. Kumar explains, “All the research on aerobic bacteria has been done in cold countries which are better suited to oxygen-utilising bacteria.”

Meanwhile, anaerobic bacteria is better suited for warmer climes. “With it, energy requirement for sludge treatment is low, as are the chemicals required for sludge-processing,” he says. The sludge mass produced by anaerobic bacteria is lower too. The other roadblocks, says Kumar, include a lackadaisical Pollution Control Board, and the money that can be made in contracts for procuring motors and components for traditional STPs.

However, Kumar remains optimistic given the governments’ push towards more responsible sewage-treatment. Diligent enforcement should make way for eco-friendly and economical solutions. “My main rival is the public drainage system. That’s because it offers a zero-cost solution to a builder’s waste treatment woes. The authorities need to be stringent with the rules,” he says.