This year began on a desolate note. If it were a movie, it would have the background music of a plaintive violin and the visuals of dipping line graphs, showing the falling pace of GDP growth, economic activity and employment opportunities. Na koi umang hain, na koi tarang hain. Then, instead of Asha Parekh finding romance and happiness with Rajesh Khanna, she would walk into an “M Night” Shyamalan movie. 2020 got darker, with people unsure about their jobs and shut out from the world to save themselves from a constantly mutating virus. It seemed like a series of nightmares, with memes on the next disaster, which some speculated would be an invasion by hostile aliens. But, we are here to tell you that a happier story has been playing out in another corner, the corner with a sense of ‘ad-venture’.

This year began on a desolate note. If it were a movie, it would have the background music of a plaintive violin and the visuals of dipping line graphs, showing the falling pace of GDP growth, economic activity and employment opportunities. Na koi umang hain, na koi tarang hain. Then, instead of Asha Parekh finding romance and happiness with Rajesh Khanna, she would walk into an “M Night” Shyamalan movie. 2020 got darker, with people unsure about their jobs and shut out from the world to save themselves from a constantly mutating virus. It seemed like a series of nightmares, with memes on the next disaster, which some speculated would be an invasion by hostile aliens. But, we are here to tell you that a happier story has been playing out in another corner, the corner with a sense of ‘ad-venture’.

With that forced pun, we are pointing to the venture-funding universe. Here, though initial days were unsettling, with business travel restrictions and valuations done over Zoom calls, investors and founders have managed to find their feet and start sprinting again. There are more pitches being heard and bigger cheques being written.

The general sentiment in the venture world is that digitisation, even under compulsion, has provided several opportunities and has snuffed out bad financial behaviour. Sajith Pai, who is a senior member of the investment team at Blume Ventures and is building a research platform for the firm, says that more pitches can be heard and at a faster rate because meetings have gone digital. “We are also seeing it become easier for high quality and second-time founders to pitch to multiple venture capitalists, and deals are getting very competitive,” he says. There is global interest in Indian companies now, as edtech, fintech and SMB SaaS adoption and trial “shoots through the roof”.

Parag Dhol, managing director at Inventus Capital India, says this crisis has made founders more responsible. He saw people cut back on spending “very early and very deep”. “Their losses may go down significantly, but discipline will definitely go up,” he says. BlackSoil Capital’s co-founder and director Ankur Bansal says there is a greater focus on profitability now, an attitude he sees carrying into the next fiscal. “In the past, many start-ups pursued unsustainable customer acquisition strategies and growth targets to inflate their valuation. The pandemic has forced such companies to focus on healthy unit economics and profitability. Growth focused and high cash-burn start-ups have had to turn to extensive cost-cutting measures and layoffs just to survive,” he says.

Personally, too, there have been pleasant discoveries. Mayank Khanduja’s six-year-old son took coding classes online and aced it. “I didn’t know he had a knack for it,” says the managing director of Elevation Capital (formerly SAIF Partners), grinning widely. Niren Shah, managing director and head of Norwest Venture Partners India, saw his father who barely used WhatsApp before the lockdown, sign up for digital yoga classes. Hemant Mohapatra, partner at Lightspeed India Partners, realised that he could avoid trips to the ophthalmologist. He had an eye test done from home.

So, overall it has been good, with a few fallouts. At the start of the lockdown, as Khanduja says, it was not easy to make a connect with the founders since it was a new way of working for everyone. It used to take a couple of meetings earlier but, with time, they realised it needed five or six Zoom calls to build that chemistry with the founders. For another, the current state of affairs makes serendipitous discoveries, such as running into founders with interesting business ideas at coffee shops or at events, tougher. Khanduja recalls how he was at their portfolio company Sharechat’s office where he happened to meet founders of another interesting start-up, FRND, a dating app. “We ended up investing in that company,” he says.

Whatever the pandemic has done, it hasn’t crushed this spirit of entrepreneurship. Therefore, in honour of this spirit, we train our scopes to the horizon and bring you trends and opportunities you can expect to see in the coming years.

SaaS is and will remain king

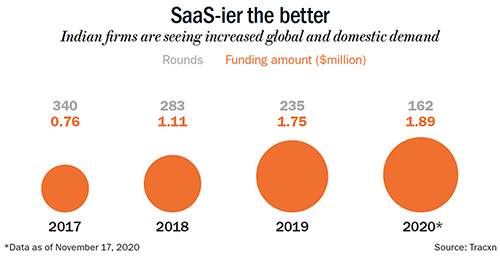

One theme almost everyone is thrilled about is SaaS (software-as-a-service). Indian SaaS companies are getting business from global MNCs and local, small businesses. Anand Lunia, founding partner, India Quotient says, “Good quality SaaS software is highly valued now.” No business wants to risk their data or operations on cheap solutions. Lunia believes that this opportunity, of investing in a business model with predictable revenue, and the availability of cheap capital has caused SaaS companies’ valuation to shoot up by 2-5x in the past six months. He sees this leading to a shift in investor and entrepreneurial interest from consumer tech to enterprise tech (See: SaaS-ier the better). “Many entrepreneurs are now saying let us make software for the global markets. Every founder is now thinking we were wrong to go after consumer, we should go after global business market,” he says. Even Norwest’s Shah sees an uptick in made-in-India, built-for-the-world SaaS solutions.

While there is global demand, locally, too, there is tailwind. Lunia of India Quotient, which has backed start-ups such as Vyapar and Khatabook, says, “In tech adoption among SMEs, we have advanced by a few years, if not more.” Blume’s Pai calls the pandemic lockdown “a positive shock” in spurring digital adoption. Just as smaller businesses surprised India Quotient with their willingness to pay for software, many offline companies such as the NBFCs in Norwest Venture Partners portfolio surprised the VC firm by hiring CTOs (chief technology officers).

While there is global demand, locally, too, there is tailwind. Lunia of India Quotient, which has backed start-ups such as Vyapar and Khatabook, says, “In tech adoption among SMEs, we have advanced by a few years, if not more.” Blume’s Pai calls the pandemic lockdown “a positive shock” in spurring digital adoption. Just as smaller businesses surprised India Quotient with their willingness to pay for software, many offline companies such as the NBFCs in Norwest Venture Partners portfolio surprised the VC firm by hiring CTOs (chief technology officers).

Even Dhol of Inventus Capital, who seems to carefully consider every trend, says that they had not expected SMEs to get so comfortable with tech and using digital distribution channels. There are still concerns over converting these SMEs into paying customers, as Pai says, “much of the big growth has been in products such as Khatabook that are free products”. To accelerate this conversion, Elevation’s Khanduja suggests sachet-based or usage-based pricing since SMEs would be willing to pay for any value-adding service.

Lunia believes the next decade will see 70% of unicorns come from this segment, with consumer tech receding, and says that even the top VCs can sense the potential. He recalls a conversation he had with the head of a top VC firm, who said he has never bet on a SaaS company before and that he needed to learn. It can be a tricky bet. For one, it isn’t easy to estimate revenue. “A minor deviation in long-term retention could result in significant change in revenue projection,” says Lunia. Therefore, SaaS companies look expensively valued in the initial years but cheap in hindsight.

Also, SaaS adoption is heavily dependent on overall tech adoption in the industry, which is further dependent on multiple competing forces, such as government policies or an unexpected catastrophe like the pandemic. “SaaS business is less probabilistic than, say, consumer businesses, and VCs have to do a bit of what PE investors do… dig deep into numbers,” he says. Adds Lunia, with a laugh, “If I am evaluating six SaaS start-ups, for three, I will say a prayer and then invest.”

Credit-tech goes up a notch

Weird credit requests and stranger collateral are rare but real. In the US, there are loans extended to buy ‘ugly’ or distressed homes and, in Hong Kong, a financier accepts Chanel and Gucci bags as collateral. Such imaginative financing may never come to India, but specialised lending has piqued VC interest.

Chiratae Ventures’ executive director Karan Mohla sees specialised lending taking off next year. In fact, this October, his firm pumped $5 million into GetVantage, a start-up that provides alternative financing for e-commerce and D2C brands. The VC firm had noticed that many brands, that are digital-first, accelerated during this lockdown and needed financing for advertising and sales. “We asked ourselves, can a traditional lender help these companies when they are starting up or do these companies need a specialised approach. Our understanding was they needed the latter,” says Mohla.

Blume’s Pai sees innovative lending solutions taking off on the back of Open Credit Enablement Network (OCEN), which was launched this July and was applauded for democratising credit. This network allows any service, be it an aggregator or a small business, to ‘plug-in’ a credit facility for its consumer. The party that hosts the ‘plug-in’ (called the loan service provider in OCEN jargon) can ask the borrower for his/her financial data, then tailor it to a standard (through OCEN), and finally, pass it on to a lender in order to assess and underwrite the loan. So, if a boutique needs credit to buy cloth from its supplier, the supplier could host the ‘plug-in’, pass the boutique’s financial data through OCEN and abracadabra! A bank loan is made available to the boutique.

While these new experiments in credit-tech are being cheered on, fintech may move beyond credit-tech. Rahul Khanna, co-founder of venture debt fund, Trifecta Capital, believes the fintech innovation engine will chug away from credit-tech and move towards investment-tech and insurance-tech. “This is a natural phenomenon,” he says. Fintech usually starts with payments, then evolves to credit, then to insurance and finally into investment. While banks in India have largely provided savings account and credit to customers, fintech wants to offer neobanking for millennials, by servicing their needs from savings and payments to credit, insurance and investments.

Partnering with venture debt

While the world was pre-occupied with credit, venture debt had started rocketing 2019 onwards. In 2020, too, start-ups have been making a beeline for debt funds, instead of trading equity for a cheaper price amidst uncertainty. “Seems venture debt’s time as an asset class has finally come,” says Trifecta Capital’s Khanna. Even banks have shown interest in the space, after the RBI gave them the go-ahead to invest up to 10% of the paid-up capital in Cat-I or II Alternative Investment Funds (AIFs). Private equity (PE) and venture debt funds (VDF) fall under Cat-II.

“VDFs and angel investors generate significant return, and banks want some of that exposure to spice up their overall return,” says BlackSoil’s Bansal. But, Khanna feels it will not be an easy transition. For one, it requires a change in mindset for a traditional bank, which is unfamiliar with funding rapidly growing start-ups or one that hasn’t yet made a profit. For another, venture debt falls under AIFs and the RBI requires banks to provision for them as they would while investing in equity.

This means higher capital allocation, though the return is not like the ones seen in equity investments. “This obviously makes it hard for banks to commit a lot of money into venture debt,” he says. Khanna, therefore, sees banks partnering with firms like Trifecta, which already has three banks as LPs, to understand and engage with this asset class. Banks may then begin to provide services other than credit, such as managing the salary accounts of portfolio companies or help with bill discounting.

Gaming takes off

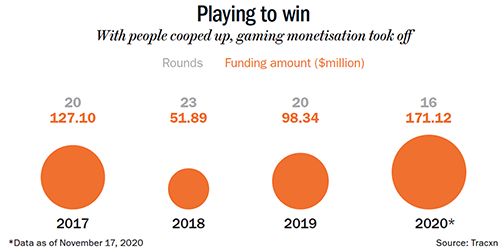

Last year, a 28-year-old American gamer with teal-coloured hair, Tyler Blevins, made nearly $20 million through his followers. That is nearly 300x the average salary of a managing director in India, and that was before the pandemic struck and expanded the gaming population by many multiples across the world. Little wonder that VCs are excited about the pull of this sector (See: Playing to win).

Norwest’s Shah says, “We hadn’t done too well when compared to our Southeast Asian counterparts, but, now there are a lot of youngsters interested. The behaviour has spread during the lockdown, with youngsters spending more time on video games and laptops.” Chiratae’s Mohla, too, has observed this trend. “While the gaming industry has grown at a fast pace in India over the past few years, 2020 saw a dramatic increase with over 350 million gamers in the country,” he says. Monetisation of various gaming formats has picked up too, according to Mohla, and not just in the big cities but in Tier-II and Tier-III cities, as well. “Micro-payment mechanisms and bit sized/small ticket purchases will greatly help in increasing this trend of monetisation in the coming years,” he adds.

Norwest’s Shah says, “We hadn’t done too well when compared to our Southeast Asian counterparts, but, now there are a lot of youngsters interested. The behaviour has spread during the lockdown, with youngsters spending more time on video games and laptops.” Chiratae’s Mohla, too, has observed this trend. “While the gaming industry has grown at a fast pace in India over the past few years, 2020 saw a dramatic increase with over 350 million gamers in the country,” he says. Monetisation of various gaming formats has picked up too, according to Mohla, and not just in the big cities but in Tier-II and Tier-III cities, as well. “Micro-payment mechanisms and bit sized/small ticket purchases will greatly help in increasing this trend of monetisation in the coming years,” he adds.

Elevation Capital is looking at real-money gaming, where users have to pay to play, as opposed to casual gaming, which is free to users and the sellers make money through advertising revenue. You would think that Indians gravitate to the latter, free model but, according to Khanduja, casual gaming is small here. Real-money gaming also has economics suited to India. Here’s why: It is expensive to acquire Indian customers and that upsets a ratio, VCs keep a keen eye on. This is the LTV (lifetime value or how much you can make from a user) to CAC (customer acquisition cost or how much you have to spend to acquire a user) ratio. Users spend only 20-25 days with a game, and a seller needs to make 2x or 3x the cost of acquiring the user to be lucrative. In India, LTV of a casual game is only 1-1.5x CAC because the cost is high, whereas in developed markets, LTV is 2-3x the cost.

The cost of customer acquisition is high for casual games here because the games have to compete for the attention span of the user, versus not just other India-based casual games but also international games, social media platforms and OTT platforms. “Given the deeper monetisation pools for the latter platforms, they can advertise (promote their product) much more heavily, thus raising the CACs for casual games in India,” says Khanduja. While the cost is high, the monetisation of casual gamers in India through ad revenue remains low. This is because of the low CPMs (cost per mille, that is for every thousand impressions) casual gaming platforms are able to charge, especially when these games are played by people on low-end devices, which the advertisers interpret as lower purchasing power.

Elevation Capital is investing in a start-up that makes the best of the cultish-following gamers have. It allows you to stream live games of players from different platforms. That is, you could watch the best win battles in Call of Duty, strategise in Counter-Strike or go Ninja on dropping fruits. After the PUBG ban, some concern around regulatory risk is discernible, but Khanduja says there is a greater understanding about the industry and that the government realises that the games depend on skill.

Some online games, such as poker, had been trapped in a grey area where the government could not decide if it was skill that was deciding winners or luck like in gambling. Khanduja says, “Like any new space, regulations are bound to evolve as the sector evolves.” According to Shah, there is no regulatory worry. “As parents, we would love for that (some level of regulatory oversight to disrupt video-binging) to happen. But, it will not happen,” he says.

Edtech crosses barriers

As parents and children are trying to get a handle on the new way of life, another tech is marching ahead with a confident stride. “Edtech has been the biggest beneficiary of COVID, given that there is willingness to pay here,” says Blume’s Pai. Even the attitude of schools towards this tech has undergone a sea change. Lunia says, “For the longest time, schools treated technology as competition. But now, it is heartening to see everyone including teachers, students and parents adopting it.”

But, VCs are looking beyond traditional edtech opportunities that target schools and affluent urban parents. India Quotient, for example, wants to chase markets in smaller towns, a sentiment shared by many VCs if we go by the money that has flown into edtech start-ups in smaller towns (See: Relearning the ropes). “Hardly any innovation has been made for children in small towns or villages, who can’t afford more than Rs.50 or Rs.100 per month. Their school fee would come to around Rs.500 a month,” says Lunia. The VC firm has therefore backed Yellow Class that conducts hobby classes for two- to 12-year olds, but for a much smaller fee.

But, VCs are looking beyond traditional edtech opportunities that target schools and affluent urban parents. India Quotient, for example, wants to chase markets in smaller towns, a sentiment shared by many VCs if we go by the money that has flown into edtech start-ups in smaller towns (See: Relearning the ropes). “Hardly any innovation has been made for children in small towns or villages, who can’t afford more than Rs.50 or Rs.100 per month. Their school fee would come to around Rs.500 a month,” says Lunia. The VC firm has therefore backed Yellow Class that conducts hobby classes for two- to 12-year olds, but for a much smaller fee.

Rocketship, an early-stage VC fund that relies on data science to pick its winners, is crossing another invisible barrier by betting on upskilling but for blue- and grey-collar workers. Sailesh Ramakrishnan, partner at the firm, says, “Typically in education, most of the companies have been focusing on either high school or college, or preparatory courses for entrance exams. But, people have not been looking into the educational needs of say a plumber or an electrician, or a person who wants to be a data-entry operator. Now, we are seeing a lot of companies come up in this space.” The VC firm recently participated in an $8-million Series A round for Apna, which is a community like LinkedIn, but for blue-collar workers, which provides job postings and advice on training.

At Lightspeed, they are optimistic about crossing a barrier in format. Mohapatra, whose profile goes…someone who loves “scrappy, unpolished, mad-crazy founders”, believes education can be delivered through social and collaborative formats. “How you deliver the content is where the hooks are. It does not need to be a one-to-many teacher-student model. There are products and technologies that can make learning more interesting without people’s involvement,” he says. He points to Byju’s $120-million acquisition Osmo, an augmented reality company. It sells a device that can animate on screen any drawing a child makes. “It allows interaction with the world through mixed media, a combination of hands-on physical play with the power of digital platforms. Those kinds of companies are very interesting in the edtech space,” he says.

Work life balance

If animating a child’s drawing sounds magical, what about logging in for work from a beach in Goa? Or taking a Monday morning concall from a cottage in Wayanad? The lockdown has been a nuisance but you cannot grudge it as it has made working from anywhere possible, for anyone. It has scattered workspaces far and wide. Lunia is cheerful, and rightly so, when he states how it could change the hospitality industry.

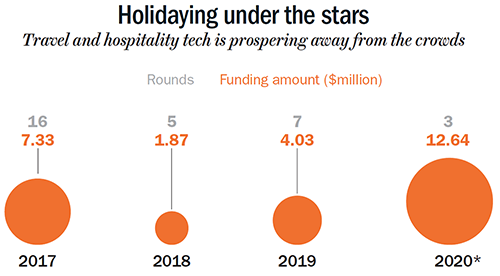

“Vacation will not be something one will take occasionally, it can be taken any day of the week,” he says, imagining people working in the mornings from these holiday spots, and signing off in the evenings to take in a starry forest sky or moonlit beaches. He thinks the trend has already caught on. When he tried to book into a place in Chikmagalur in October, the rooms were more expensive than regular days and it was only a weekday. Lunia says hotels should introduce designed-for-work packages. “I will be open to listening to any idea for this, for sure,” he says. And, investor interest is already showing in the fund flow (See: Holidaying under the stars).

“Vacation will not be something one will take occasionally, it can be taken any day of the week,” he says, imagining people working in the mornings from these holiday spots, and signing off in the evenings to take in a starry forest sky or moonlit beaches. He thinks the trend has already caught on. When he tried to book into a place in Chikmagalur in October, the rooms were more expensive than regular days and it was only a weekday. Lunia says hotels should introduce designed-for-work packages. “I will be open to listening to any idea for this, for sure,” he says. And, investor interest is already showing in the fund flow (See: Holidaying under the stars).

Rocketship’s Ramakrishnan sees a spike in creativity, with people being able to work on many different things, when they work from home. “We are expecting to see a significant wave of new creative start-ups that will come from small cities, and they will build for consumers that are very similar to them,” he says.

While work gets distributed across space and time, living could too. Shah of Norwest believes there will be something of a reverse urbanisation with people going back to towns or considering moving to suburbs. “People are staying away from urban congregations and regular tourist spots, instead opting for a small villa in outer areas. Real estate and travel will face long-term change because of this,” he says.

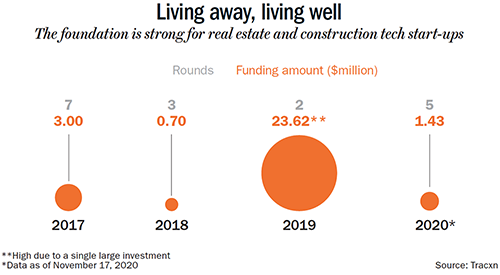

Lightspeed’s Mohapatra, too, has noticed a similar drift. “Anything that is offline and isolated, and does not expose you to COVID risk, is recovering faster. For example, Oyo is doing quite well offline now. I was surprised to see that, because I thought travel and transportation will suffer long term. But, the reason they are coming back faster than we had expected is because these are typically smaller hotels. People think that a single townhouse is lesser risk than going to a larger hotel, where there will be 100 families living together. We didn’t expect that,” he explains. The number of investing rounds has gone up in real estate start-ups in Tier-II and Tier-III towns (See: Living away, living well). The total amount in 2020 is much smaller than the previous year because, in 2019, there was one big, out-of-the-ordinary Series-A funding in Infra.Market, an online platform to procure construction materials.

From farm bills to agritech

So, unexpectedly, small is big. Another oddball favourite is agritech. Elevation’s Khanduja says that, along with digitisation, what has made agritech more attractive is the access farmers now have to new markets through the latest farm reforms. “Together, digitisation and the bills could lead to large growth in agritech,” he says. But, will farmers quickly transition into users and buyers? Khanduja believes all you need is one compelling hook, as with every customer, and for farmers, it is the promise of getting a fair price for their produce. Once a platform offers that, it can add on a whole gamut of monetisable services to it, such as selling seeds, fertilisers and equipments, or offering financial services.

Agritech was anyway becoming more dynamic across the value chain. Rocketship’s Ramakrishnan says, in the past, innovation was at its peak in produce distribution, and was present to a lesser extent in agri-input management (such as deciding how much fertiliser or water to use) and even less in B2B agritech (such as renting or leasing tractors). “Now we are seeing significant innovation in all of these areas,” he says.

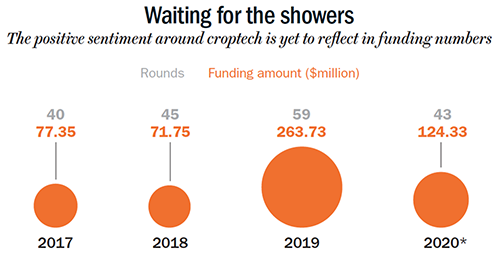

While the bills have boosted optimism around this sector, it is too early to see this reflected in new funding (See: Waiting for the showers).

While the bills have boosted optimism around this sector, it is too early to see this reflected in new funding (See: Waiting for the showers).

Website is the new showroom

Who really cared about the experience of an e-commerce website before? The attitude of a regular shopper online is similar to Ethan Hunt’s in Mission Impossible. Go in, get the goods and get out. You don’t hang around to appreciate the dull sameness of the room. But the pandemic has changed us, if we go by what Lunia says. “Consumers want to spend time on websites, like they would in a showroom. It is a trend that has become prominent post COVID,” he says.

While horizontal marketplaces such as Amazon and Flipkart are about searching for what you want, comparing prices and buying, vertical ones such as Sugar or Indya give more, such as advice on makeup, ‘looks’ of the season or fashion trends. Also, earlier people went online to get discounts. This has changed, with people going online also to splurge. The consumers are looking for the full experience of a shop on a website, and they prefer the tidiness of a vertical e-commerce portal such as Nykaa over the overwhelming everythingness of marketplaces such as Amazon.

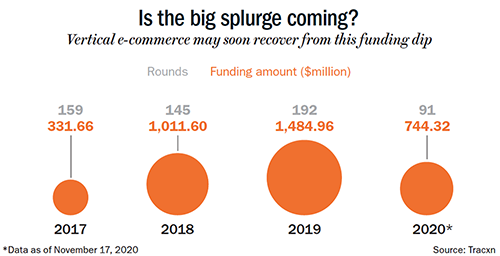

Health-tech goes vertical

Funding numbers show a drop (See: Is the big splurge coming?) in investing rounds and amounts in 2019-20, but Lunia says it is “just a phase.” The reticence has been because investments in vertical e-commerce did not do well a few years ago for “being too early and trying too hard”. He reiterates, “We will see huge investments in vertical e-commerce next year.”

It looks like it is the season for masters of one, and not one for the Jack of all trades. Even in health-tech, we are likely to see funding interest in platforms that help manage specific conditions or needs, for example, one that helps manage a chronic condition such as diabetes, as opposed to platforms that serve every need but lightly. Mohla says, “Full stack verticalised healthcare platforms have been able to grow and impact users more meaningfully than broader healthcare platforms. A focused solution that goes deeper into solving the underlying problem and not just at the discovery layer is better suited for end consumers.”

Amit Mookim, manager director of IQVIA South Asia, which provides consulting services to lifescience and healthcare companies, too, sees people increasingly going online to manage their chronic conditions. He says, “Many chronic conditions need not only medication but lifestyle management. Tech can bring that closer to the patient.” Earlier, Mohla says, lack of digital awareness and trust in such services, and scarcity of trained professionals, frustrated the growth of such platforms. Not anymore.

Mookim, however, believes there are still hurdles to leap over. One is that every service or product will need to have a multilingual, interoperable and user friendly interface. Two is that for AI-based products or services, the baseline is data and data is scarce in India. Truly, who amongst us records our medical history well? It is normal to see hospital discharge papers stuffed thoughtlessly into some drawer once we are back home. Old habits die hard.

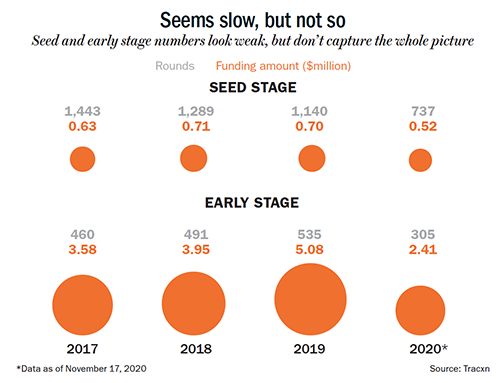

Marquee optimists in early stage

While the numbers indicate a slowdown in seed- and early-stage investing (See: Seems slow, but not so), there are marquee VCs who are betting contrary to that sentiment and with equal, if not more, conviction than before. “In fact, most of us VCs have done more investments than we expected to, and often at higher valuations than we usually do,” says Pai of Blume Ventures, which had started as a bridge between angels and VCs. He says per deal investment has gone up by 15-20% (from $800,000-$1 million, it has “crept upto” $1 million-$1.2 million in seed stage), and that the exuberance is thanks to the emergence of micro VCs, angel syndicates and super angels, and the increase in number of high quality founders.  Lightspeed’s Mohapatra says, “We have certainly deployed more capital in the second half of the year than we did second half of last year.” He agrees there was a downtrend in the initial few months of COVID but adds the data lags in capturing industry sentiment. That is because most start-ups don’t immediately announce their fundraise. He says it is in these trying times that the best-in-class founders will emerge. “They don’t care that their market is completely undefined, they don’t care if they don’t know what the market will look like in two years from now. They just want to start companies. This is what they would have done regardless of the market. And, those are the ones that tend to be the best founders to back,” he says.

Lightspeed’s Mohapatra says, “We have certainly deployed more capital in the second half of the year than we did second half of last year.” He agrees there was a downtrend in the initial few months of COVID but adds the data lags in capturing industry sentiment. That is because most start-ups don’t immediately announce their fundraise. He says it is in these trying times that the best-in-class founders will emerge. “They don’t care that their market is completely undefined, they don’t care if they don’t know what the market will look like in two years from now. They just want to start companies. This is what they would have done regardless of the market. And, those are the ones that tend to be the best founders to back,” he says.

After that impassioned defense, Inventus’ Dhol provides a sober counter point: “I will be surprised if this pace of activity continues in early stage. I am really puzzled at the number of angels investing. In the last recession, angel activity disappeared.” Dhol, in fact, believes that the Indian ecosystem has a group of angels who do more harm than good. They invest in a start-up without fully understanding the model, give a short runway of nine to 12 months to a founder to start generating profits and pull the plug, when it does not happen. Although this group has been immensely beneficial to the ecosystem, he feels, “The truth is somewhere in between.”