On a split screen, a young girl and a boy, in seemingly small-town India, flirt with each other for 15 seconds before the clip goes off the feed. Welcome to TikTok, an impressively popular short-video platform where 50 million people from this country have already registered. That is more than a fifth of Facebook subscribers in India. TikTok, started in 2016, allows users to create 15-second videos, soundtracked by a music clip.

Next, a young woman from a nondescript north eastern Indian city has her audience captivated as she live-streams one of her singing sessions from the comfort of her room. The screen is showered with ‘diamonds’. Each ‘diamond’ can be redeemed by the performer for a payout later. All of this is over LiveMe, an 18-month-old app.

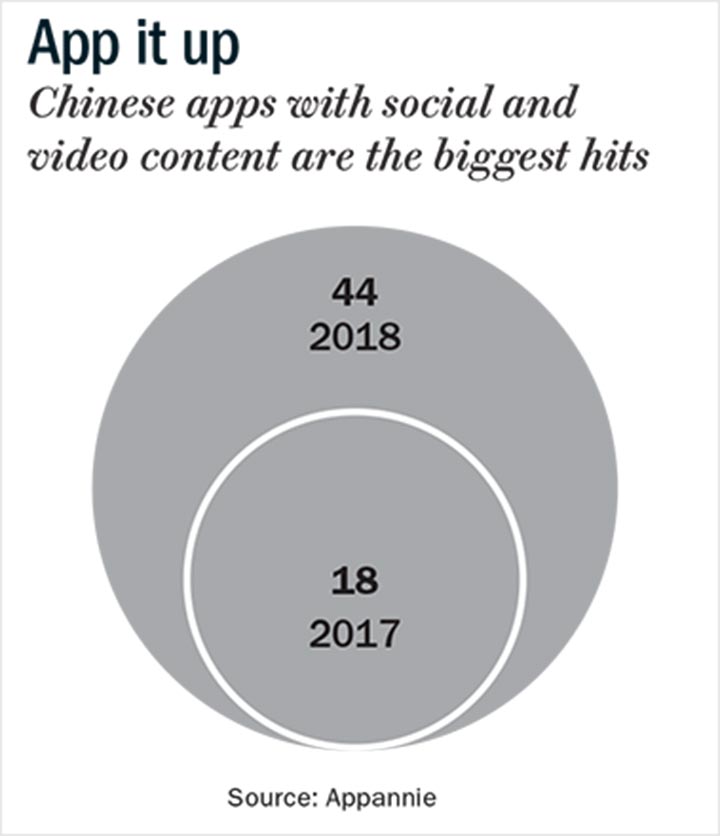

What is common between these two apps? Both are Chinese, and not very old — less than two years. The two are among several Chinese apps that have rapidly gained popularity in India. In 2017, the top 100 Google Play store apps had 18 Chinese apps and, in 2018, this number shot up to 44 (see: App it up). These apps cut across categories but social and video content apps have been the biggest hits. Among the social-content platforms are Helo (a regional language only social network) and SHAREit; and among short-video and live-streaming apps are LiveMe, Vigo Video, BIGO LIVE; and among entertainment apps are TikTok, Kwai and LIKE. A growing number of Chinese apps now feature on the list of top apps in India. (see: Gaining ground)

Rapid growth

Anchit Goel is a man with a very specific line of experience; that of working with Chinese internet companies for a decade. Sitting in his Cyber City office in Gurugram, he talks about Cheetah Mobile. It is a New York Stock Exchange-listed internet company which has 535 million users globally, with 70% of them outside of China. Amongst it’s products are utility apps such as Clean Master (a memory-cleaning app) and LiveMe. Cheetah Mobile has been present in India for four years and is expanding its team here. Although they don’t disclose India numbers, Clean Master has over one billion downloads on the Google Play store, while LiveMe has garnered about 50 million downloads on the same space.

“LiveMe was launched one and half years back in India. Then we hardly had any users. We have since seen phenomenal success here, gaining more than 13 million users. Three out of four users use the app every day,” claims Goel.

Not very far from Cheetah Mobile’s office is ByteDance’s, in WeWork co-working space in Gurugram’s Cyber City. The $78 billion Chinese internet technology behemoth has 800 million daily active users across its platforms globally. ByteDance has apps such as Toutiao (a news recommendation platform), TikTok, Vigo Video and Helo. According to market research firm, Sensor Tower, TikTok is the most downloaded app on Apple App store in Q1 CY19.

And ByteDance is taking India very seriously. It has taken pains to develop an India specific product — the social network Helo. Download the app and you’re in for a surprise. English is not an option. You have to choose one of the regional languages to remain on the platform. It’s like a vernacular Facebook with 40 million monthly active users.

Shyamanga Barooah, head of India content operations at ByteDance, has a terribly sore throat today. Yet, he is happy to talk about the growth of Helo. “From its launch in June 2018, we have reached 40 million monthly active users… which is a fantastic number,” says Barooah. Most of the users of this social network, available in 14 Indian languages, are from the non-metro areas.

The Chinese behemoth Alibaba Group hasn’t directly entered India as an e-tailer, but it launched its UC Browser here early, in 2009. In 2016, UC switched its strategy and launched a news/ content app under the same brand. Currently, their revenue comes from advertising and partnerships. Damon Xi, general manager of UCGlobal Business, Alibaba Digital Media and Entertainment Group, says they have 130 million active users in India.

Road to millions

Ask any Indian app publisher about user acquisition, and they will tell you it is an uphill task. Hitting a million users on Google Play store is considered a landmark. But the Dragon has reached this number with ease (see: Playing for keeps). How?

First is right timing. Satish Meena of Forrester Research says a few things have changed during the past two to three years. “With the coming of Jio, we have seen a large increase in number of internet users and mostly from Tier-II and Tier-III cities. Online, they consume content (both video and audio) and they use messaging. The Chinese apps have specifically targeted them with live-streaming and social media,” he says. In smaller towns, there is a preference for these over Facebook because of their use of local language.

While ShareChat, an Indian company has been doing the same thing for past four years, Meena says it is not in the same scale. “The Chinese companies leverage the experience they have gained back home. They know what content will work and how to scale it up for smartphone,” he says. The non-urban audience in both countries are similar in size, age profile (mostly young millennials) and have a preference for more localised content/platform. They’re dissimilar in their paying capacity and online-paying habit.

Roposo, a Gurugram-based social-media platform with over 10 million users, competes with Helo and ShareChat. Its founder Mayank Bhangadia says that Chinese companies started tapping the Indian market five years back, after the market back home was saturated. “They are spending an irrational amount to acquire users,” he says. Industry experts say the companies spend anywhere between $5 million and $10 million on marketing. It is a big spend, but they are loaded. ByteDance for example, is the world’s highest-valued start-up at $75 billion. They have spent millions in China to gain users, even incurring a loss of $1.2 billion last year.

Ujjwal Chaudhry of Bengaluru-based RedSeer adds, “They are playing in India with a Chinese playbook, not an Indian one.” Their winning strategies include having high percentage of user generated content (UGC). From TikTok to UC Browser, all of them allow millions of people to upload terabytes of content onto the platform. Their second strategy, according to another expert, is minimal moderation in content generation. “Instead, they like to build an user base by allowing racy content,” says the expert, on condition of anonymity. The third strategy is splurging on marketing and the fourth, extensive localisation and personalisation. They also operate with an element of bravado. Chaudhry explains why: “The Chinese ecosystem has a high failure rate. There are more start-ups there, as compared to the US, so there are more failures too.”

At ByteDance’s Helo, Barooah says the success largely lies in harnessing the localisation opportunity. “According to reports, in India, 90% of new Internet users over the next five years will be regional language users,” he says. Over the past eight months, Helo has engaged with scores of regional icons here. “We have some really good influencers for Hindi world, such as Ashutosh and Ved Pratap Vaidik, and Hansika Motwani, an actor with more than a million followers,” he says.

Helo has tied up with Bigg Boss Karnataka and, for Gujarati users, it built a promotional campaign around the popular Makar Sankranti festival. “Bigg Boss Kannada tie-up was for the first time a TV channel tied up with a social media app. Users could select tasks for the players and had a say in the selection of the season six winner. The overall engagement was more than 200 million,” says Barooah. Right now the focus is on acquiring users, and not so much the revenue.

If Helo engaged with influencers, live-streaming platform LiveMe tried a different tack. “Our focus has been to provide a platform where any user from any part of India can come on the platform, live-stream and showcase its talent,” says Goel. But it wasn’t enough.

Therefore, Goel and his team went many steps ahead. They created two studios, one in Delhi and second in Mumbai, for use of selected talents. “We work with a lot of singers, comedians, fitness and dancing talents. We bring them from Tier-II and Tier-III cities, create specific shows and allow them to broadcast live from our studios,” he says. Helo also ran a quiz on the app with a daily prize of $1,000.

Goel believes this multiplied their user base. “If I’m streaming online, my friends and relatives will come and watch me online. They will invite more people to come. Word-of-mouth strategy was more important for us than paid-app uploads,” claims Goel. That is a divergence from the general attitude of Chinese-app publishers who are notorious for pushing paid-app uploads.

Shrenik Gandhi, who runs a digital-marketing agency White Rivers Media, sees the Chinese apps as disruptors. “Google has recently termed 3Vs (Voice-Vernacular-Video) as the future. My belief is that these apps are getting all 3Vs right at the same time in India,” he says. “Tier-II and Tier-III users have now found a space to air their opinions with a lot of noise. Also, Chinese platforms have a laser sharp focus on user-generated content and content sharing. The lingual communities are very close knit, if the content sharing is in their language, it grows fast.”

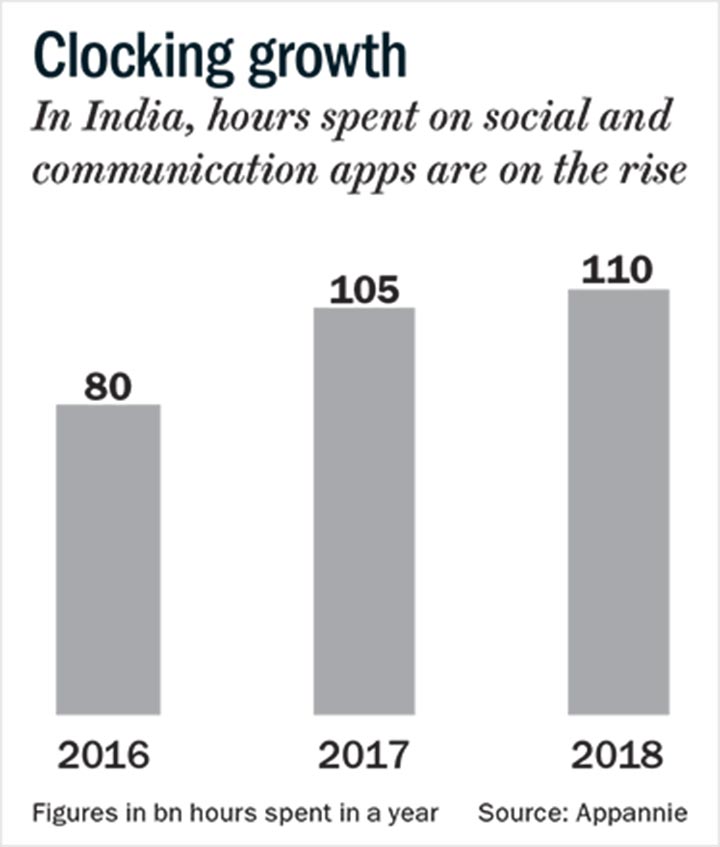

UCWeb too resorted to localisation. From 2016, when they became a news-feed service, they started partnering with Indian publishers. To date, they have partnered with more than 350 media groups here. In the entertainment space, UC has partnered with Bollywood production houses such as Zee Studios, RSVP Movies and Red Chillies Entertainment as their online entertainment trending partner. “Data shows that each Indian user spends 20 minutes a day, on an average, reading and watching content provided by the UC’s general news feed. Indian smartphone users spend 1.1 hours on average on entertainment content every day” says Xi (see: Clocking growth).

Chinese app-publishers believe in adding the local colour and in bold strokes. “WhatsApp and Facebook have nothing specific for India market. After a while, people tend to get bored,” says Goel. Meena agrees: “The fresh features of TikTok and Helo are attracting youngsters.” TikTok has unique features such as 3D stickers and image/video recognition while Helo recently added a multi-image feature and ability to add music to images.

While US and European publishers leave a lot of white space to keep it uncluttered, Chinese apps are crowded with features. “You don’t see that aggressiveness in WhatsApp, Google or Facebook. They would launch a single feature, after a year, that too for global market,” says Goel.

Way forward

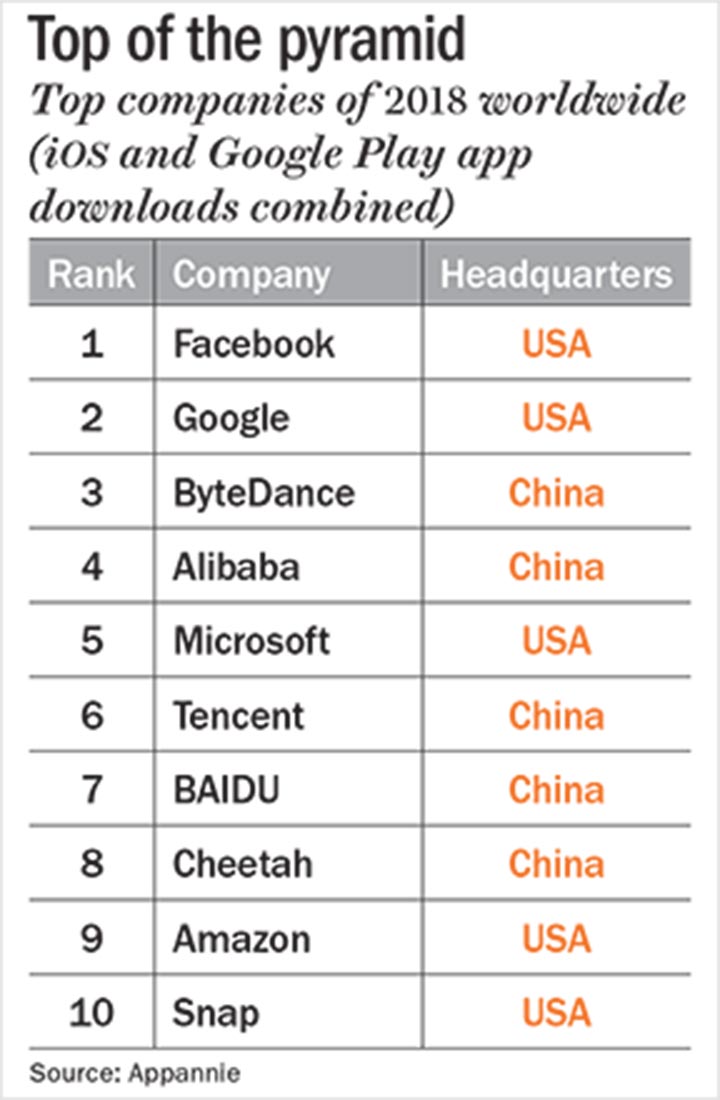

While Chinese content-apps have won the first round, that of customer acquisition and to some extent retention (see: Top of the pyramid), the future path is paved with difficulties say experts. The first challenge would be monetisation and the second would be getting away with unmoderated content.

There are two ways to monetise apps — either advertisers pay or the user pays. “The average revenue per user for even Facebook are low in India compared to even Southeast Asia,” says Meena.

Some players have this factored into their plan. Goel knows that India is a long-term market. “Most of the Internet companies are focusing on spending in Indian market and no one is making money… Even though people are consuming a lot of online content, they are still not into the habit of paying,” he says. While Cheetah Mobile’s other apps make money through adverts, LiveMe is built around an in-app purchase model. People (viewers) have to buy diamonds, at #10 for 15, and gift them to broadcasters (performers) during the show. LiveMe gets a 10 to 20% commission when a broadcaster redeems those diamonds.

“We have had users who have made a thousand dollars every month. On an average, performers make around $200 to 250 a month,” says Goel.

ByteDance does not make any money at the moment. They hope to make their profits from advertising in the future. Their TikTok, though, features a few in-app-purchases such as emojis and digital gifts. At this stage, the app’s focus remains on user-base growth.

Then there is the second drag, of content moderation. Typically, the UGC platforms are open platforms and users can generate any kind of content. At times, the content borders on pornography. Indian laws are riddled with ambiguities and are weak in moderating this content.

TikTok disappeared from the Google Play store and and Apple’s App Store in mid-April 2019, after the Madras High Court asked the Centre to ban the app, citing its worrying content. The court said TikTok encouraged pornography and warned that children could be at risk. The ban was later lifted by the Madras High Court. The company says that it welcomes the decision. “While we’re pleased that our efforts to fight against mis-use of the platform has been recog-nised, the work is never ‘done’ at our end. We are committed to con-tinuously enhancing our safety fea-tures as a testament to our ongoing commitment to our users in India,” a company spokesperson says.

In China, the state has strict regulations. So, the same companies keep large teams to moderate content but, in India, there is no similar kind of pressure from authorities. There is also the additional hurdle in India — of multiple languages with varying accents. The free-for-all nature of these platforms in India may become a big barrier between potential advertisers and platforms.

Bhangadia of Roposo believes that Chinese apps have used such unethical means, of gossipy news, clickbait headlines and raunchy videos, to grow users. “Currently their platforms are men-heavy, lured by racy content. This seems to be a very short-term approach and they’re oversimplifying India. Brands would be very conscious about being associated with any such platform in the future,” he says. But all three Chinese companies — ByteDance, LiveMe and UC — deny the use of such content. “We have kept our platform clean. We are building it for long term,” says Barooah. Going by the content, TikTok and Helo seem to have actually made an effort towards this. Till date, Helo has taken down more than 160,000 accounts and five million posts which were found violating its community guidelines.

Gandhi is already seeing brand interest in TikTok. “Two dozen brands, mass-oriented ones, have shown interest,” he says. His agency ran a campaign over the platform last year for Shah Rukh Khan’s movie Zero. “I was surprised by the response. The audience is very receptive,” he says.

Chaudhry says that UGC is also worrying for bringing down the quality of online content. “We believe that the content industry in India will evolve with high quality, publisher-generated monetisable content,” he says. Chaudhry believes that GDP per capital is higher in China, than in India, and therefore people at the bottom-of-the-pyramid there have more disposable income. Therefore, even low-quality content can be monetised in China, unlike in India.

Clearly, it is not going to be an easy ride for these apps. But Meena says, “There are not many markets which can give hundreds of millions of users. It would be a volume play from the monetisation point of view.” So, they’ll just keep ‘tiktoking’ till then.