Rajiv, Shweta and their two and a half year-old son Chinmay are a happy family settled in Gurugram. Life is a well-oiled machine until one night, at the witching hour, when Rajiv is woken up by the toddler. A sobbing Chinu, as he is lovingly called, keeps mumbling, “Mujhe kyun maara?” Brushing it off as a nightmare, Rajiv pats him back to sleep. But a week later, the incident repeats. This time, the parents are concerned. “It can’t be a coincidence,” says Shweta. The next day, they decide to take him to the family doctor…

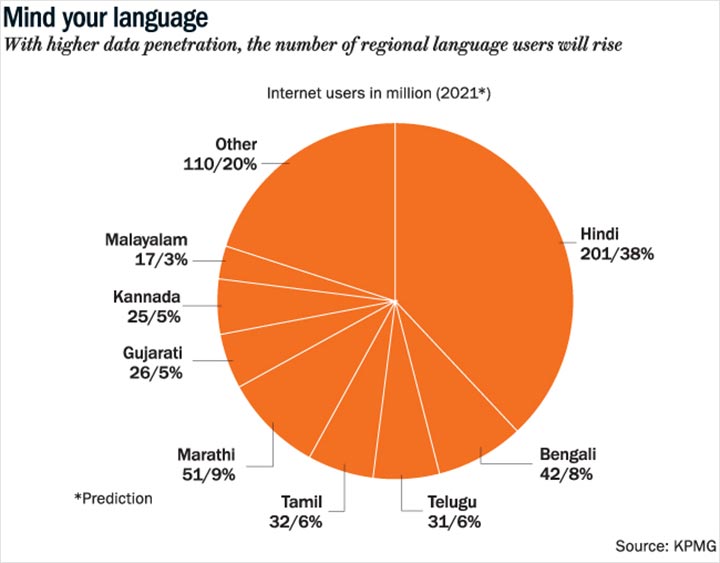

The story, written in Hindi, continues on Pratilipi, where it has become one of the “top 20 best short stories”, read by almost 90,000 users. With 20 million monthly active users (MAUs), 2.3 million stories and over 235,000 writers, Pratilipi claims to be India’s largest self-publishing platform that supports 12 languages, spoken by 90% of the total population in the country. “Today, the educated English-speaking man in India also wants to consume and create in his native language,” says Sreedhar Prasad, former partner with KPMG India & Kalaari Capital and co-author of a KPMG India-Google report Indian Languages – Defining India's Internet that expects the number of Indian language internet users to reach 536 million in 2021 (See: Mind your language). On one hand, there is huge demand for regional content; on the other, supply is limited. Naturally, platforms such as Sharechat (think Indian Facebook) and Vokal (think audio version of Quora) have also seen a rise in popularity in recent years. And to give voice (or the power of a pen through a keyboard) to this desi audience, Pratilipi has been scripting an interesting story.

The Prelude

Tired of not finding anything good to read in Hindi, Ranjeet Singh, a bibliophile from Rae Bareilly and an engineering graduate, decided to take matters into his own hands. “English was ruling the internet and I thought the world should be a little bigger than that,” says Singh. He and his colleague Sahradayi Modi quit their cushy corporate job at Vodafone and got together with Prashant Gupta (schoolmate, who has now left the team), Sankaranarayanan Devarajan (engineering batchmate) and Rahul Ranjan (MBA batchmate). After interacting with 300 small-time and aspiring writers, they realised the need for a storytelling platform that didn’t force authors to think in English.

That’s how the self-publishing platform was born — one where any writer could publish articles, stories, fiction or non-fiction, share them with friends or family, and receive feedback from readers. It was conceived as a community of readers and writers. After all, back then, TikTok wasn’t all the rage and users had longer attention spans.

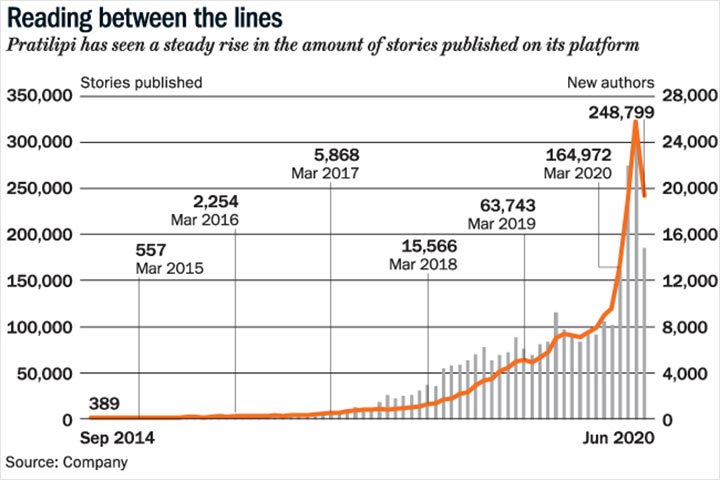

Onboarding more than half of those writers they spoke with was their first victory. That was followed by publishing classic works of RamcharitManas, Premchand, Malik Muhammad Jayasi and others, which were available in public domain. As users shared their stories via Pratilipi on other social media platforms, the app gradually gained popularity. “More content was published this month on Pratilipi than that by the organised publishing world in India,” says Pratik Poddar, principal, Nexus Venture Partners, one of the investors in the start-up. In June, over 248,000 new works were published on the platform. (See: Reading between the lines).

The platform’s deep engagement with its audience — with its forum for readers to interact with authors and discuss their favourite stories, language experts to guide writers, and regular new content —is what drew its investors. The start-up has raised more than $30 million in funding with backing from the likes of Tencent, Qiming Venture Partners, Times Internet and others. On average, a user spends about 60 minutes on the app every day, while a web user spends 14 minutes. “Pratilipi has helped a significant portion of the consumers become creators themselves,” says Siddharth Nautiyal, investment partner, Omidyar Network India Advisors. In fact, 90% of new writers on the platform actually start as readers every month.

Pratilipi’s investors believe the start-up could do so much more in the regional content publishing space. “From blogging, Q&A, discussion forums and blog networks, the opportunity is fairly big,” says Abhishek Mitra Gupta, managing partner, TVentures – venture fund backed by Times Internet. Keeping this in mind, Pratilipi’s team of 65 employees is working on building strong product offerings.

The next chapter

But the next feat the start-up has to achieve is what makes any business a “business” — making money. The company has several plans in place, but no intention to monetise its content anytime soon. Singh says that they are considering two strategies: paywall and content licensing. “99% of the content will always be free; only 1% will be behind the paywall,” he says. For instance, if a reader has read 10 chapters, she may have to pay a nominal fee of Rs.5 or Rs.10 to finish the entire novel. The other option is to offer a monthly subscription package where the user pays Rs.50-100 to access all content. Singh adds that they are still in the strategizing phase and no number is concrete since for the paywall to work, they will need high quality content. That will require curators to identify content and editors to polish them. Currently, Pratilipi has no editorial team as they are mainly focusing on product development and customer management.

Ujjwal Chaudhry, associate partner – consumer internet, RedSeer Consulting feel profiting from this model seems like a tall order. “While micro payments might work, the team will have to bring onboard people or influencers who can generate high level of following and write good quality stories,” he explains. Writers could then share their revenue with the platform.

Singh believes that content licensing is where the big money is. To explore that, the company is looking at production houses to license some of its stories that can be turned into TV shows, movies, web series or even video games. And in a world where OTT rules, Lipika Bhushan, head-marketing and publicity, MarketMyBook says, “Platforms such as Netflix, Hotstar and Amazon Prime are aggressively developing content in regional languages. So, this stream can be a better revenue generator for Pratilipi.”

Then, there is the third option, according to experts and investors — advertising. “There is massive opportunity for contextual advertising, using the deeper reader profile stats,” says Prasad. For instance, if a 24-year-old is reading stories on travel, then MakeMyTrip can be a potential advertiser. Besides, they could also explore sponsored content. “If in a story, a father-daughter duo is driving a car. You could get revenue through brand placement there,” adds Bhushan. But Singh is not too pumped about advertising lest they hinder user experience. He asserts that the goal is to get to 50 million MAUs and a million writers by June 2021 and only then will they start focusing on revenue. For now, they have cash that will sustain their operations for more than three years.

Similarly, they are also not worried about big publishers edging them out. “Their strength is curating and distributing in the offline world. Ours is technology. Their and our strengths are different,” says Singh. A spokesperson for one of the biggest publishing houses in the country, who did not wish to be named, admitted that they would not consider competing with Pratilipi, which is more a tech platform than a publisher. “Such platforms need a different kind of ecosystem and for big organisations to give up on their existing ecosystems is neither possible nor advisable,” adds Bhushan of MarketMyBook.

Only one player has tried it so far — Juggernaut Books. By building an open platform for writers in 2017, they discovered many authors and have inked 50 publishing contracts so far. “Being a publisher, we can offer personalised feedback, use our authors to conduct writing workshops and offer a solid platform for amateur writers,” says Simran Khara, CEO, Juggernaut Books. But their platform is nowhere close to Pratilipi’s size, with two languages support, 1.5 million readers and 1,500 writers.

Even when compared with other players in this space, Pratilipi is ahead by a wide margin, in terms of users. Its competitors Matrubharti, Kahaniya and Storymirror are all experimenting with different revenue models such as advertising, proofreading and ghostwriting. For instance, Matrubharti, which was founded in 2013, already has a paywall and sponsored content. But it has only about 30,000 authors, 3 million readers and supports eight languages.

In the meantime, Pratilipi is not kidding around on customer acquisition. To expand their user base, they have also launched Pratilipi FM for audio stories and podcasts and Pratilipi Comics. Launched in January and March, these platforms already have 250,000 and 500,000 MAUs, respectively. While anyone can narrate/upload their stories on the FM app, the comics app will open up for self-publishing only after two years. “It will take some time to build a strong algorithm for the app that can detect and suggest high quality comics,” says Singh. For now, the team has licensed comics such as Chacha Chaudhury and Pinki, including some new-age cartoonists. Singh says they expect to start generating profit only four to five years from now. Until then, they are confident that as long as Indians have stories to share, they will continue to grow. Seeing that this country of 1.3 billion is awash with stories wild and crazy, Pratilipi may just write itself a happy ending.