India’s government and those in charge of its monetary policy want to do away with food prices as a measure of inflation. The suggestion was made in the Economic Survey released on July 22 and reiterated by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in its August bulletin. If authorities decide on going through with the move, a nation of 1.4 billion people, which the Global Hunger Index (GHI) says has a “serious” hunger problem, will not account for food while framing its monetary policy.

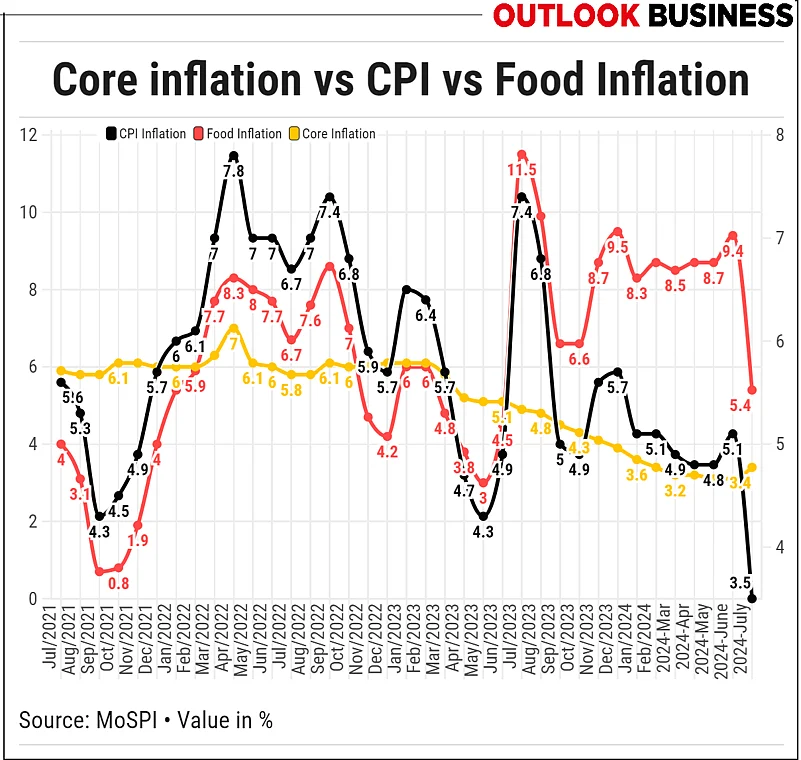

The Economic Survey’s recommendation comes at a time when India has been struggling to lower food inflation for several quarters. Food inflation in India remained at or over 6.6 per cent between July 2023 and June 2024. The first drop in months came in July this year when food inflation was at 5.9 per cent, still a relatively high figure. This in turn has stopped the central bank from revising interest rates.

Much of the Indian population spends nearly 40–50 per cent of its household income on food, according to the Household Consumption Expenditure Survey (HCES) carried out by the National Statistical Office (NSO) in 2022–23. That fiscal, rural Indians spent 46.4 per cent of their household income on food while urban Indians spent 39.2 per cent.

Removing food from inflation considerations could be misleading because food and beverages account for 54.18 per cent of the consumer price index (CPI), according to a section of economists. These economists argue that food and fuel inflation have a strong impact on inflation expectations and therefore it is important to give food a central place in policy decisions.

Doing Away with Food

The government wants to remove food prices from the inflation target because it says monetary policy cannot address supply-side issues, which it believes is the reason for consistently high food inflation. The Economic Survey argues that monetary policy is designed to tackle short-term problems related to overall demand and food prices do not fall under its ambit.

The government is concerned that sticky food inflation is keeping headline inflation (the measure of inflation that accounts for everything including volatile items like food and fuel) high. The latest RBI bulletin noted that core inflation (measure of inflation without food and fuel) has been decreasing since the 2023 fiscal because of monetary policy measures and the easing of cost-push measures.

Core inflation does not take food and fuel prices into account because it regards the prices of these goods as too volatile to be able to offer a clear picture of the economy. For example, a drought that lasts a small period may temporarily raise the prices of food, but these effects eventually correct themselves. While headline inflation would account for such a change, core inflation would not.

“From a central government perspective, they would probably like to see a lower interest rate in the absence of any significant possibility of the inflation push now,” says Indranil Pan, chief economist, Yes Bank. But Pan says, “Given that there is very close linkage of food to the core, it will be absolutely injudicious to remove food from [inflation] consideration and just argue in favour of the core.”

Prithviraj Srinivas, chief economist at Mahindra Group, says, “Core inflation is derivative and may not appreciate. For example, if headline inflation is running at 8 per cent but core inflation is calculated at 4 per cent, monetary policy messaging can become too convoluted.”

Considering the volatility of food and fuel prices, the monetary policy committee (MPC) has a wide 2 per cent band around the 4 per cent target. “If we choose a core CPI of 4% as a target then we should ideally narrow the band to say 0.5–4%,” says Srinivas.

Dwindling Household Savings

Indians have seen a consistent decline in household savings the past few years. Household savings in India dropped from 22.7 per cent of GDP in 2021 from 18.4 per cent in 2023. In 2022–23, net financial savings reached a five-year low of Rs 14.2 lakh crore, down from Rs 17.1 lakh crore in 2021–22. This while spending on food has remained around 50%. Excluding food prices from the inflation target will at such a time might paint an inaccurate picture of the economy.

Namrata Mittal, chief economist of SBI Mutual Fund, says, “Most Indian households earn less than Rs 5 lakh per year and spend over 50% of their income on food. Therefore, it is crucial for both monetary and fiscal policies to address this significant impact of household inflation. Monetary policy cannot ignore such an important category which today forms 46% of the CPI basket.”

.png?w=550&auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&format=webp&dpr=1.0)

The Stickiness of Food Inflation

Indian authorities have been battling sticky food inflation for a while now. While the Economic Survey argues this food inflation is due to supply-side issues, several economists disagree. They say monetary policy has indeed helped bring down food inflation and more sustained efforts will bring it down further.

The RBI in its monetary policy report said food prices were sticky in 2020 because of multiple overlapping supply shocks due to climate events in the more recent period that impacted the spatial and temporal distribution of monsoons, induced sharp increases in surface temperatures and caused unseasonal rainfall.

“India has a huge population, so the consumption level is always on the higher side. A slight disruption in the supply causes a huge impact in food prices and hence on inflation rates,” says Ravi Singh, senior vice president, Retail Research, Religare Broking.

Mittal of SBI Mutual Fund says, “Food inflation can impact core inflation through higher labour costs. Additionally, the government benefits from lower borrowing costs, which are influenced by lower repo rates.” She says that by targeting headline inflation, the RBI could encourage the government to implement supply-side reforms that stabilise food prices.

The exclusion of food prices from monetary policy considerations will raise fundamental questions about priorities in India’s economic governance. For a nation where a significant portion of household income is devoted to food, this shift might offer short-term relief but at the risk of overlooking the very real, day-to-day struggles of its citizens. Food prices, however volatile, cannot easily be disentangled from the broader economic picture.