Rajesh Kumar Raghav is a farmer from the hinterlands of Bihar. He toils tirelessly under the scorching sun, cultivating the very crops that sustain his family and countless others. Despite the challenges, Rajesh works hard, knowing that his efforts contribute not only to his family’s survival but also to the nation’s food security. The Indian government, recognising the pivotal role of farmers like him, implements various schemes and subsidies to support them.

Millions of India’s poor are unaware, but their nation fought for them tooth and nail at the recently-concluded 13th Ministerial Conference of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in Abu Dhabi. In five days of intense negotiations, India fought off developed nations on fisheries subsidies and public stockholding to ensure food security among other issues.

What stood between India’s poor and the developed world’s intent to take away their subsidies was the WTO’s consensus system, a system that requires unanimity among all member nations.

India’s minister of commerce and industry Piyush Goyal called the failed consensus a win for India. “We have not lost out on anything. I go back happy and satisfied,” the minister said. “India successfully pushed the food security issue and the country did not yield any ground on protecting the interests of poor farmers and fishermen, as well as on other issues.”

The European Union (EU), on the other hand, was expecting for a breakthrough in negotiations on these issues. Deprived, it expressed disappointment at the outcome.

“We were disappointed with the lack of breakthroughs in other areas. The European Union engaged intensively on fisheries subsidies, agriculture, and WTO reform. Agreements were within reach, supported by a big majority, but ultimately blocked by a handful of countries – sometimes just one,” said European Trade Commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis.

For India, this victory means the country has to fight hard to protect the consensus system, which is facing challenge from a number of developed nations, including the United States and some EU countries. The advanced nations plan to undermine the consensus system and replace it with voting.

The US, which has already laid an assault on the WTO by blocking the appointment of judges to its Appellate Body in 2019, has openly criticised the consensus system for not leading swift decisions and making the 29-year old global body inefficient.

India, over the years, has consistently safeguarded its agriculture and manufacturing sectors at the WTO by building consensus. New Delhi, therefore, advocates for the consensus system at a time when it feels might stand to lose if a voting system comes in.

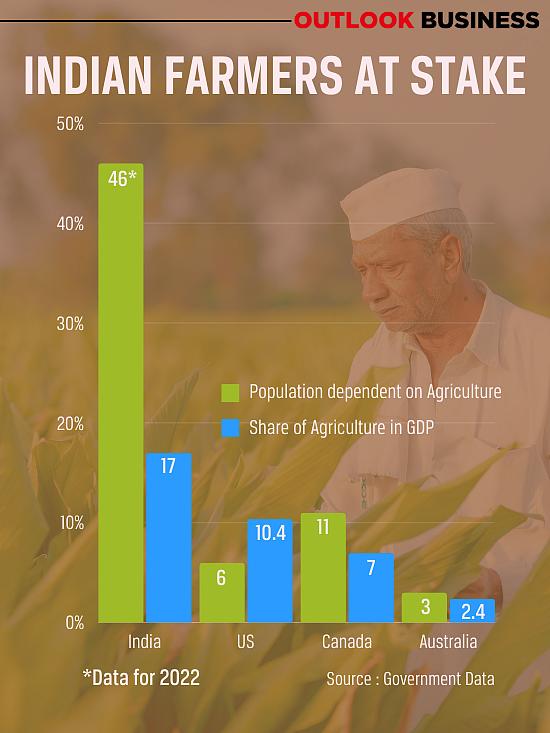

“Our priorities are very clear as of now. We cannot compromise on the 60 per cent of our population who are dependent on agriculture in negotiating with countries where that proportion is below 5 per cent. Export reserve is a priority, yes, but food security supersedes everything,” a senior official at the ministry of commerce told Outlook Business, requesting anonymity.

A Tussle of Priorities

India’s decision to stand by the consensus system comes at a time when it is facing an onslaught from the US, Canada and other developed nations that claim India distorts the global food market with its public stockholding and subsidies to farmers.

For the world’s most populous nation and other developing countries in Africa, the priority is domestic food security. They seek to be more flexible in offering more farm support, beyond the current 10 per cent subsidy limit. For instance, India informed the WTO that the total value of its rice production in 2019-20 stood at Rs 3,82,595 crore, of which it gave subsidies worth Rs 52,402 crore or 13.7 per cent.

On multiple occasions, India has surpassed WTO’s threshold on subsidising farmers by invoking the “peace clause” agreed upon at the Bali conference in 2013. This is because India’s public stockholding programme is crucial to ensure affordable rice and wheat for more than 80 crore people.

Under this program, the government procures food grains such as rice and wheat directly from farmers at MSPs, which are prices set by the government to safeguard farmers' interests and ensure a fair return on their produce.

At the WTO Ministers’ Conference in Abu Dhabi, India was not open to discussing any other agricultural issue unless a permanent solution is found to food security of developing nations.

“India’s stance is crucial because first of all it represents the long-term interests of one-sixth of the world’s population. Second, it is not just championing its own cause at the WTO, but is committed to the agenda of the developing nations and the Global South,” says Srinath Sridharan, a policy researcher and corporate advisor.

“The needs of the Global South today are very different as they emerge out of the shadows and need a voice,” he adds.

The clash between India and developed countries does not end with protecting farmers, however. According to the commerce ministry official, India also sought leeway to subsidise poor fishermen in developing countries.

India is the third largest fish producer in the world, behind China and Indonesia. Vietnam and Bangladesh are other major fish producers. Meanwhile, developed nations are placed significantly lower in fish production.

“Voting in WTO means all the big guys enforcing rules that the small ones do not want to follow. Basically, they will be taking decisions for everyone,” says Biswajit Dhar, professor at Council for Social Development.

But, can that happen?

The West’s Quest for Voting

Developed nations say their objection with the consensus mainly revolves around the gridlocks of the method. An example of that is the failure of the Doha Development Agenda, launched at the Fourth Ministerial Conference of the WTO in November 2021.

The aim was to address issues related to trade liberalisation, development and equity, particularly focusing on the needs and interests of developing countries. But negotiations stalled over disagreements between developed and developing countries, with no significant progress in recent years.

At that time, it was India, which criticised the US and the European Union for subsidising their farmers and distorting the global market in the process. “It is ironical that they say we are distorting the market today, when they themselves do it,” the ministry official said.

“India has a completely different situation than these (developed) countries. Majority of the farmers consumes what they produce here, so most of it does not even come to the internal market, forget the external,” he added.

In the early 2000s, the US Farm Bill provided billions of dollars in subsidies annually to American farmers, whereas, in Europe, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) has long been a major source of agricultural subsidies.

Many such disagreements between India, among other developing countries, and the US and the Europe contributed to the failure of the Doha Agreement at the time.

Discussions on potential reforms to the decision-making process at the WTO have gone on for years. There has, however, not been an instance where replacing the consensus system was formally proposed. It was only part of discussions within the organisation.

Need Consensus to Replace Consensus

A former WTO official who did not wish to be named says developed nations could not prepare ground for the proposal. This is because as per rules of amendment, a consensus is required to make changes to the decision-making process.

“Consensus is very much part of the DNA of the system. It would require close to consensus among the important members to change that,” says Lorand Bartels, professor of international law at the University of Cambridge.

The discussion on consensus and voting comes at a time when the significance of the WTO is diminishing. Nilanjan Banik, professor at Mahindra University attributes this trend to the proliferation of bilateral and regional trade agreements.

He suggests the erosion of the global trade body could potentially become a platform for geopolitical maneuvering, which developed economies might exploit to further their interests.

Divide and Conquer

Of the 164 members of the World Trade Organization (WTO), more nations are classified as developing than developed. But this does not mean developing nations are at an advantage. In many cases, interests of developing nations are in conflict with each other.

“There are some issues on which developing countries might form a coalition against developed countries; others where the coalition will comprise of developed and many developing countries,” says Bartels. “In addition, developing countries are often competitors, and in certain sectors they can be completely developed.”

In the Doha Round itself, India faced pressure from developed and developing countries to make concessions on its agricultural policies. The US and the European Union sought greater reductions in tariffs and other trade barriers from developing countries, including India, as part of the negotiations.

Biswajit Dhar who has formerly taught WTO Studies at Indian Institute of Foreign Trade, says developed countries have gained confidence in their influence and that is why they want to replace consensus with voting.

“At the time of its (WTO) formation, these developed countries were in support of consensus because they believed they would get outvoted by the developing nations. But today they feel confident that they can buy their loyalties,” he says.

India has won many of its battles at WTO with the help of the consensus method. While the nation has joined forces with fellow emerging economies in trying to conserve that method and protect the likes of Rajesh, there might be another battle looming large where every nation fights for itself.