Part of what the epic choices of literature and history have to teach us lies in the inverted wisdom of failed decisions, the mistakes we can learn from, either because they point to some nagging feature of the human mind that undermines us or some failing of our environment that sends our choices down the wrong path.

In the summer of 1776, Washington’s initial mistake was to even defend New York in the first place. It was, by every account, a hopeless cause. Outnumbered by the British two to one, and facing an impossible disadvantage in terms of sea power, the smart move would have been to surrender the city. “It is so encircled by deep, navigable water that whoever commands the sea must command the town,” Lee wrote to Washington. But Washington seemed incapable of contemplating giving up such a valuable asset so early in the fight.

After he had committed to defending the city, Washington made a series of crucial tactical errors in deploying his troops. Unwilling to bet decisively on whether Howe would attack Manhattan Island directly or attempt to take Long Island first, Washington spread his troops between the two locales. Even after word arrived in late August that British troops had landed at Gravesend Bay, near modern-day Coney Island, Washington clung to the idea that the landing on Long Island was a mere feint, and that a direct attack on Manhattan might still be Howe’s true plan.

Washington did, however, send additional regiments to guard the roads that led through the Heights of Gowan — at Bedford, Flatbush, and Gowanus. Each of those roads was so narrow and well protected that any attempt to thread the British forces through would result in heavy losses for Howe. But Howe did not have his eye on those more direct routes to Brooklyn. Instead he sent the vast majority of his troops all the way around to the farthest point of the Heights, to the Jamaica Pass, in one of the great flanking moves of military history. In doing so, he exploited to deadly effect the most egregious mistake of Washington’s entire career. While Washington had dispatched thousands of troops to guard the other three roads, only five sentries were planted near a lonely establishment named the Rising Sun Tavern at the entrance to the Jamaica Pass. The five men were captured without so much as a single shot fired.

Once Howe moved his men through the rocky gorge, he was able to make a surprise assault on the rebel troops from the rear. While the Battle of Brooklyn raged on for another seventy-two hours, it was effectively over the moment Howe made it through the Jamaica Pass. Within two weeks, New York belonged to the British, though Washington did distinguish himself by plotting an overnight evacuation of all his ground forces from Brooklyn — shielded by a dense fog that had settled over the harbor — a move that managed to keep most of his army intact for the subsequent battles of the Revolutionary War. This is the great irony of the Battle of Brooklyn: Washington’s most cunning decision came not in his defense of New York but in the quick confidence of his decision to give it up.

Washington’s decisions were ultimately so flawed that the American side never really recovered from them, in that New York remained under British control until the end of the war. But, of course, Washington’s side did ultimately win out over the British, and while Washington was never a brilliant military tactician, none of his subsequent decisions were as flawed as his botched attempt to hold on to the isle of Manhattan. Why did his decision-making powers fail him so miserably in the Battle of Brooklyn?

In his initial decision to defend the city, Washington appears to have suffered from a well-known psychological trait known as loss aversion. As countless studies have shown, humans are wired to resist losses more than to seek gains. There seems to be something in our innate mental toolbox that stubbornly refuses to give up something we possess, even if it’s in our long-term best interest to do so. That desire to keep Manhattan may have led Washington to make one of the most elemental mistakes in military tactics: by leaving a significant portion of his troops behind on Manhattan, he ensured that the British would encounter a greatly diminished force in Brooklyn. His only real hope would have been in doubling down on a Brooklyn defense, but instead, unable to countenance the idea of leaving the crown jewel undefended, Washington hedged his bets.

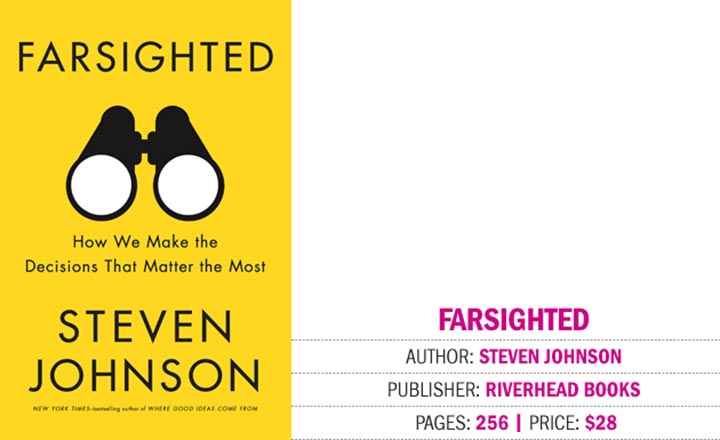

This is an extract from Steve Johnson's Farsighted published by Riverhead Books